What life on board the Titanic was really like

Touring the Titanic

PA/PA Archive/PA Images

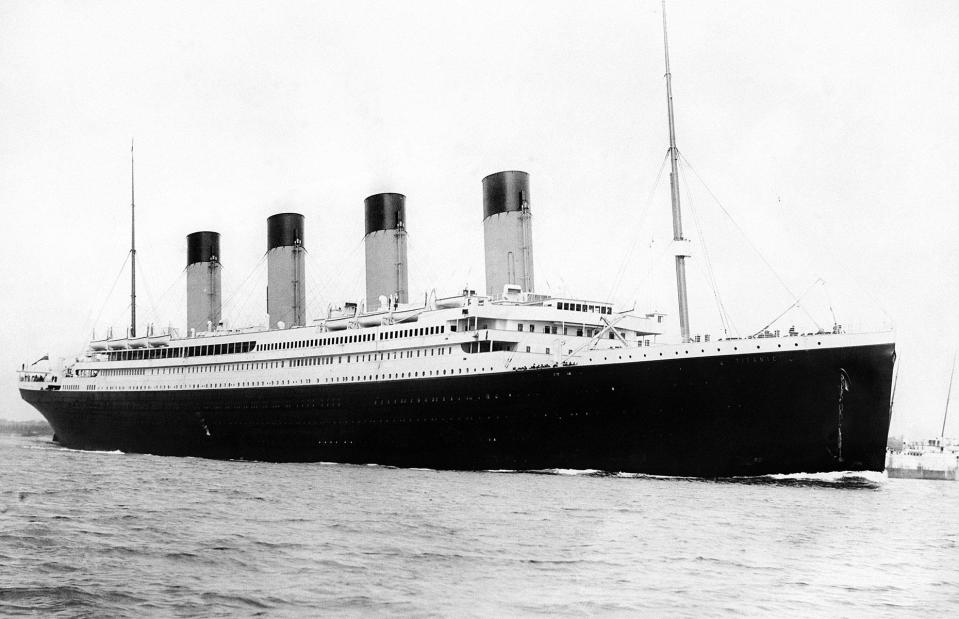

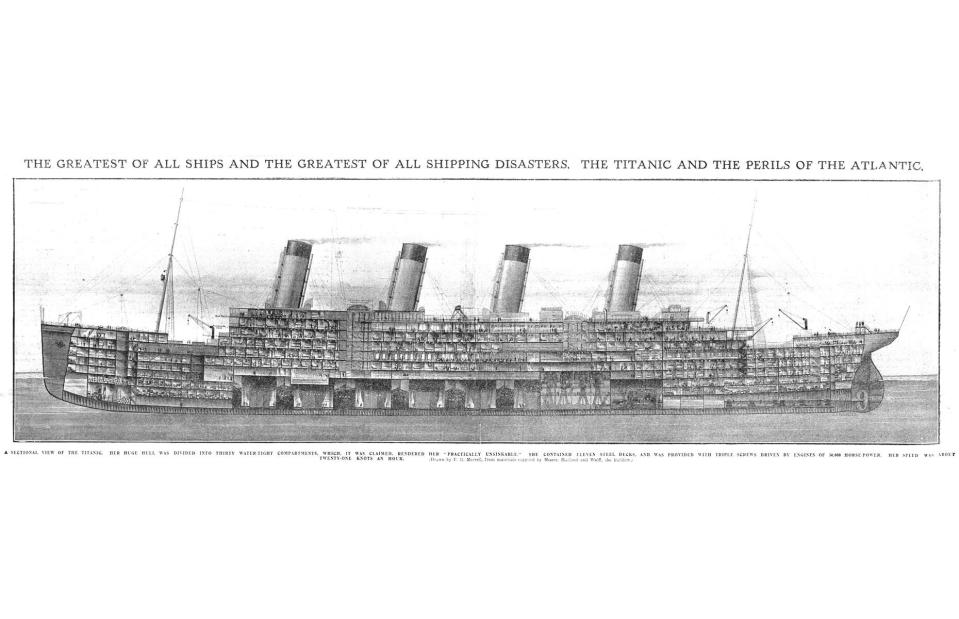

When the RMS Titanic left Southampton, England on 10 April 1912 bound for New York, she was the largest ocean liner afloat and thought to be unsinkable. More than just a ship, the Titanic was a symbol of the wealth, sumptuous tastes and engineering skill of the Edwardian age. But her collision with an iceberg in the North Atlantic on 14 April – and the loss of more than 1,500 lives – marked the end of an era. Today, more than 112 years later, the Titanic's tragic story continues to captivate.

We reveal incredible images that show what life was really like on the most famous and ill-fated voyage in history...

The creation of a legend

Georges Jansoone (JoJan)/Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

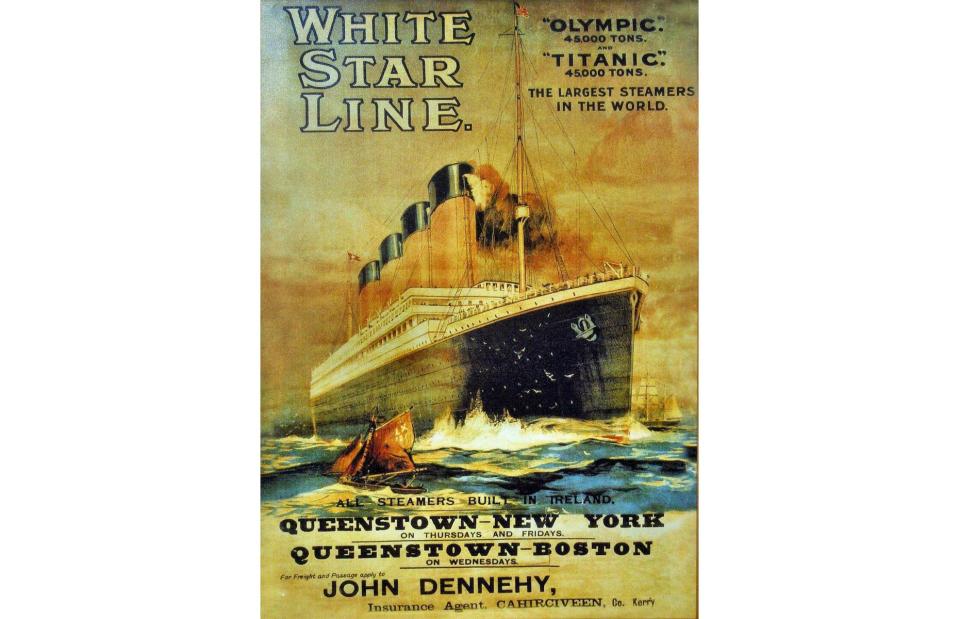

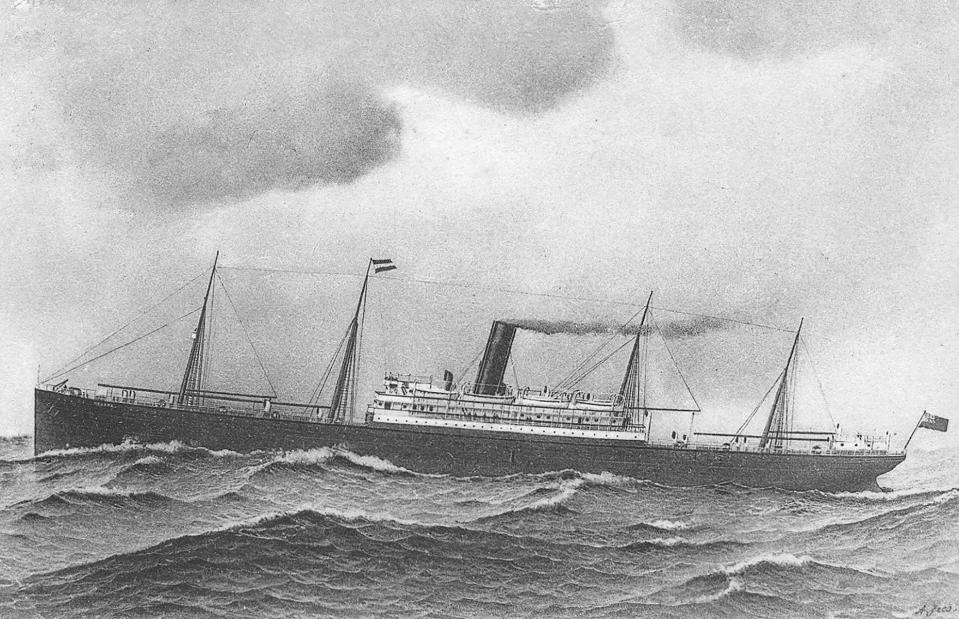

The Titanic was built during a golden age of sea travel. Growing numbers of immigrants to the New World and wealthier passengers during the early 20th century meant competition for business on Europe to New York sailings was fierce. Plans were first laid for the Titanic (and her near-identical sister ships the Olympic and Britannic) in 1907 by the White Star Line. Other companies, including Cunard, already had popular passenger ships such as the RMS Lusitania and the RMS Mauretania, and the Titanic was designed to compete with these stars of the sea.

Building the Titanic

Ralph White/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

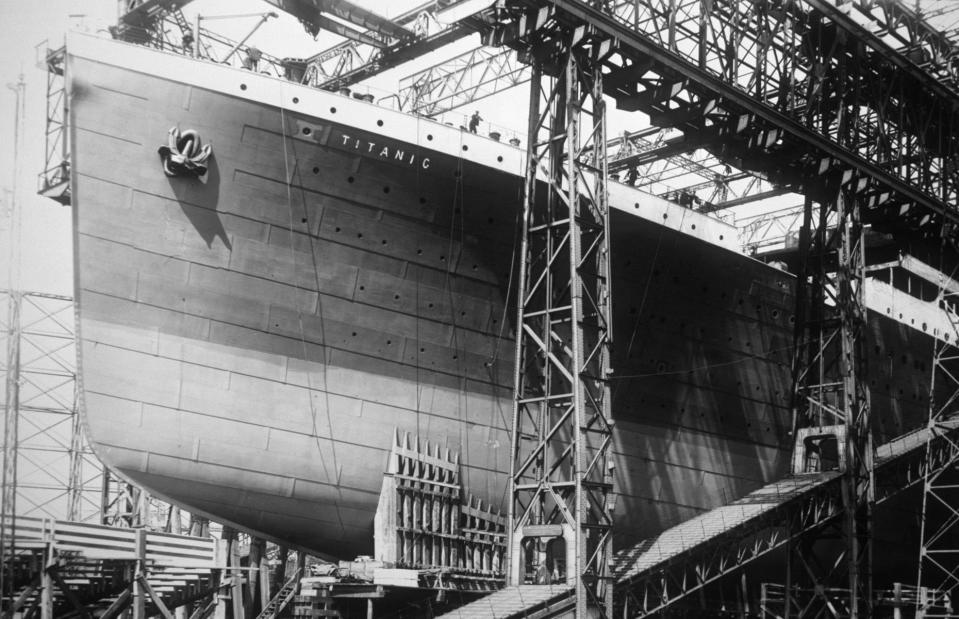

It took four years from 1909 to build the Titanic at the Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Costs were lavish at the time – around £1.5 million ($7.4m) in total, or £147 million ($192m) in today's money. Thanks to 16 watertight compartments (known as bulkheads) that could be shut to prevent flooding, the Titanic was designed from the off to be unsinkable and considered one of the safest ships afloat.

Building the Titanic

Library of Congress/Public domain

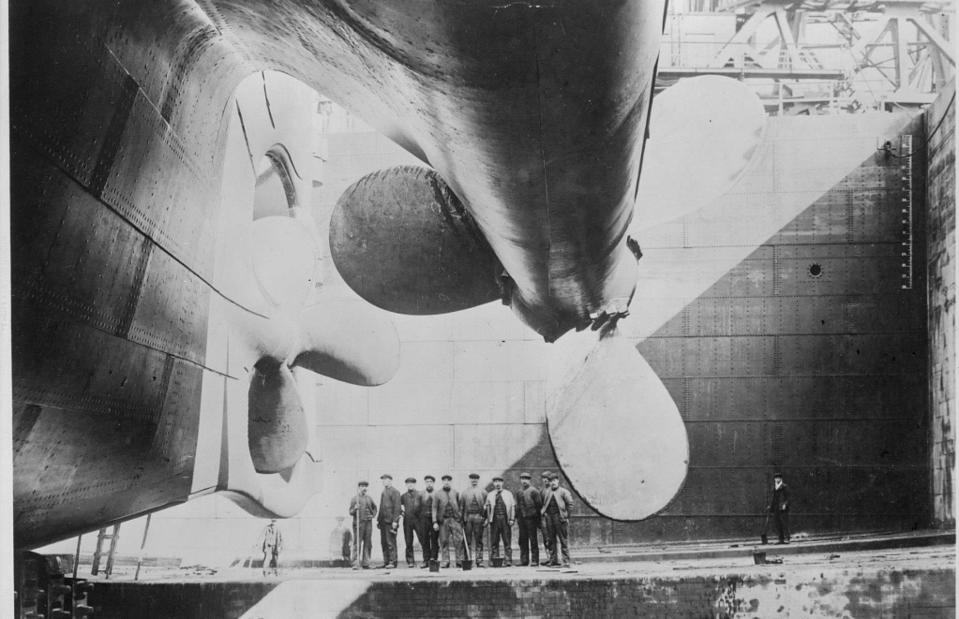

The cost of creating the Titanic wasn't just financial. Eight workers were killed between the keel being laid and her first launch, and 246 injuries were recorded during her construction. The Titanic's 26,000-tonne hull was launched on 31 May 1911 ready to be fitted out, with the propellers added later.

The ship of dreams sets sail

Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

Despite many setbacks the RMS Titanic sailed on her maiden voyage on 10 April 1912 from Southampton. The Titanic made two stops before heading out to the Atlantic Ocean, calling at Cherbourg in northern France and Queenstown (now called Cobh) in County Cork, Ireland.

A shocking near miss

Unknown author/Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

But even the Titanic's departure wasn't without drama. As she pulled away from the dock at Southampton she almost crashed into another ship. The New York (pictured right) was moored nearby and, as the Titanic was leaving, the massive ropes that held the smaller ship snapped. Only quick thinking from the Titanic's crew, who used a wash of water from a propeller to push the other ship away, avoided a collision. It was an ominous start to the voyage.

Heading into history

Ralph White/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

At Queenstown the dock wasn’t large enough to accommodate the ship so passengers and mail were ferried over to the Titanic in small boats known as tenders. Happily the weather for this portion of the voyage was sunny and bright and just after lunch on 11 April, the ship left Ireland to meet her fate. This picture is among the last images of the Titanic taken from land.

First class: the grand staircase

Ralph White/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

While at the time RMS Titanic was the largest ship afloat, the ship's appeal wasn't just her size – once on board, passengers would have been staggered by the ship's jaw-dropping interiors. The grand staircase in first class (pictured) was one of the most lavish at sea and featured a wrought-iron and glass-domed roof and oak panelling.

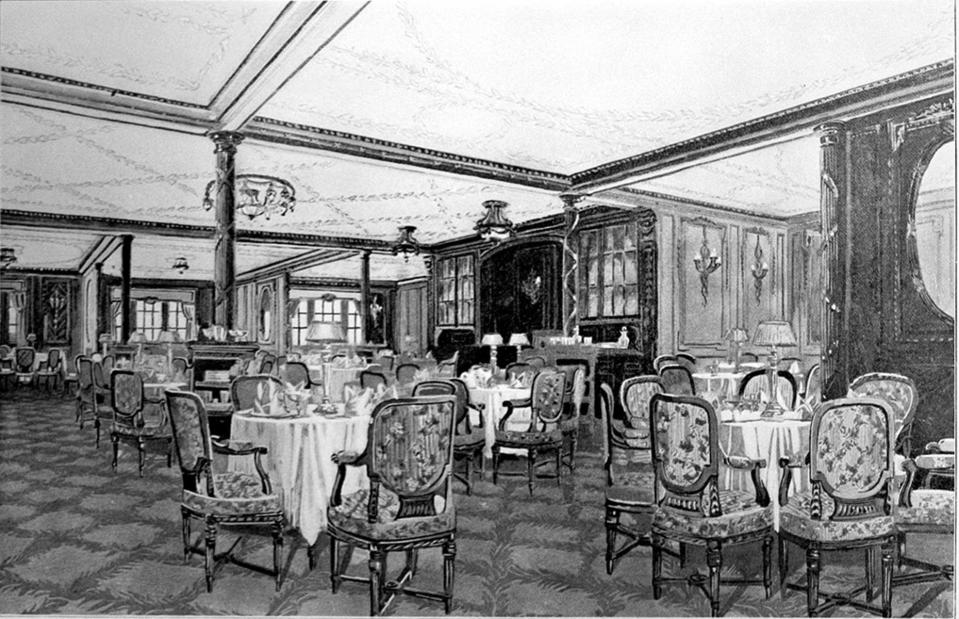

First class: dining saloon

Everett Collection Inc/Alamy Stock Photo

The 100-foot-long (30m) first-class dining saloon could be found on D Deck between the second and third funnels. This location was specifically chosen to ensure uninterrupted dining in the smooth, central part of the ship. The room featured leaded windows and Jacobean-style alcoves. First-class passengers were offered a luxurious choice of menus each evening with a selection of fine wines to accompany the food.

First class: a la carte restaurant

White Star Line/Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

For an extra cost, first-class passengers could also book to dine at restaurateur Luigi Gatti’s intimate a la carte restaurant nicknamed the 'Ritz'. Gatti had been poached from upmarket Oddenino's Imperial Restaurant on Regent Street, London to run the Titanic's high-end spots. The elegant space was fully carpeted with French walnut-panelled walls and picture windows. Small tables were lit by crystal lamps and guests could eat any time between 8am and 11pm, which made it a popular choice.

First class: Veranda cafe and Palm Court

World History Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

The options for first-class guests didn't end there. Pictured is the Veranda cafe and Palm Court, the perfect place for afternoon tea. Cafe Parisien was another spot, designed to offer first-class passengers a sea view while they dined, the first of its kind. On the night the Titanic sank the menu included oysters, pate de foie gras and chocolate eclairs.

First class: keeping fit

Robert John Welch/Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

While the lavish food was all part of the experience for those in first class, fitness and wellbeing were catered for too. Passengers could burn off the calories in the state-of-the-art gymnasium, pictured in this colourised image. It offered cycling machines, an electric horse and camel and a rowing machine. There was even a squash court below deck.

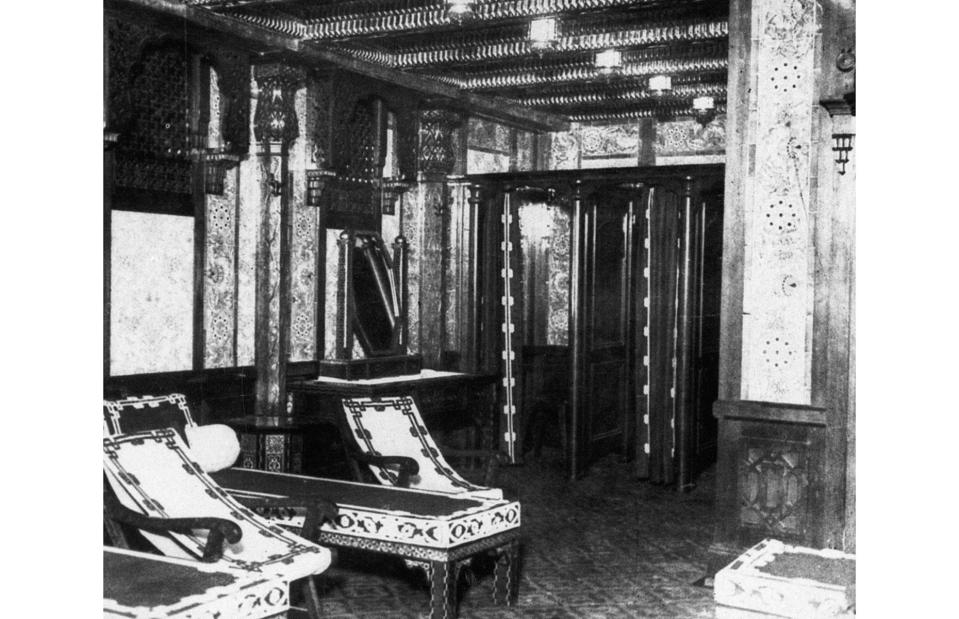

First class: the Turkish baths

Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

The Turkish baths were the height of luxury for the time. First-class passengers could visit the Moorish-inspired suite for the price of $1 dollar a day. The facilities included a steam room, hot room, cooling room, temperate room and an exciting new invention, electric beds that heated the body using lamps.

First class: swimming pool

George Rinhart/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Located in the middle deck, alongside the Turkish Baths, was an impressive swimming pool for first-class passengers only. A novel feature for the time, the 'swimming bath' was 30 feet (9.1m) long and 14 feet (4.3m) wide and filled with heated saltwater, which was pumped into the pool from the sea via a tank. The bath was available for ladies between 10am and 1pm and for men from 2pm to 6pm.

First class: smoking room

Library of Congress/Public domain/via Picryl

This first-class smoking room on RMS Olympic (pictured) would have been similar to the Titanic’s. While ladies retired to the reading and writing room after eating – they were forbidden entry – male passengers went to the smoking room for cards and Scotch.

First class: reading and writing room

George Rinhart/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

This comfortable reading and writing room was where first-class ladies retired after dinner and White Star Line stationery would have been provided for those wishing to write to loved ones back home. Books could be borrowed from the lounge next door too.

First class: staterooms

Public Record Office of Northern Ireland/R Welch/Public domain/via Picryl

The most expensive rooms on board were the four parlour suites located on B deck. Each had a lounge, two bedrooms, two wardrobe rooms and a private bathroom and toilet. They offered the latest in modern electrical appliances including telephones and heaters.

First class: staterooms

Robert John Welch/Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

Two of the parlour suites were occupied by J Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the White Star Line (more about him later). The suite pictured here, B-58, was taken by the Baxter family, from Montreal, Canada, who boarded at Cherbourg. Mrs Baxter was a widow and travelling with her daughter Mary Helene and her son Quigg (who had also brought his girlfriend Berthe Mayne on board). Tragically, Quigg went down with the ship.

First class: staterooms

Public Record Office of Northern Ireland/R Welch/Public domain/via Picryl

Those staying in one of the four parlour suites had access to one of two private interior promenades. These measured 50 feet (15m) in length and were styled in a wooden Tudor design. They were on either side of the Titanic, offering exclusive views.

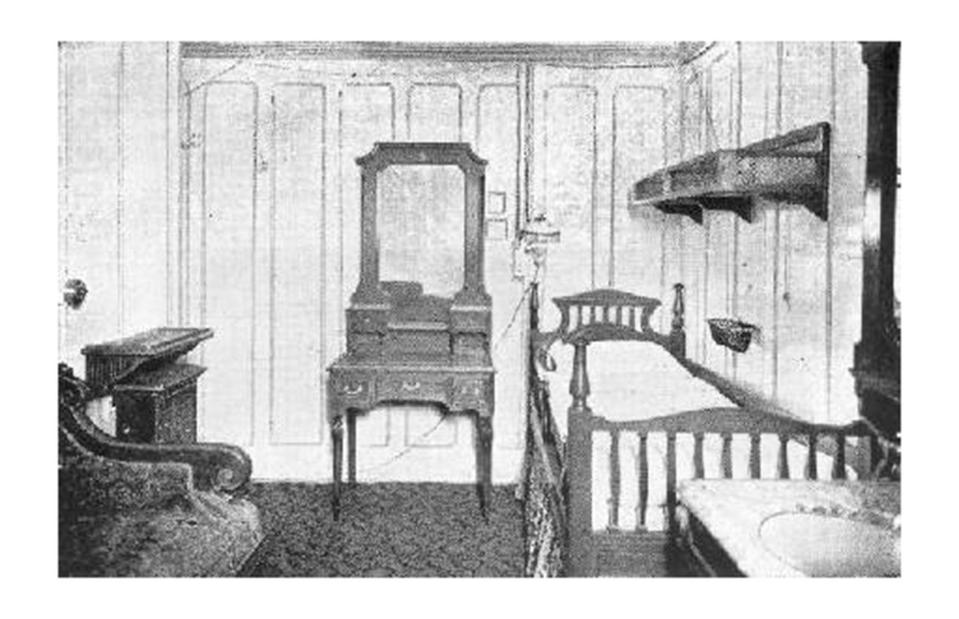

First class: staterooms

Unknown author/Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

First-class cabins were not furnished identically, but decorated in different styles including Queen Anne and Louis XV. And not every cabin in first class was as luxurious as you might think. This is stateroom B-21 which came complete with a single bed and sink. Some first-class staterooms even had shared bathrooms.

First class: the super-rich passengers

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The luxury and status of the Titanic attracted some of the wealthiest and most prominent businessmen, political figures and celebrities of the day. John Jacob Astor IV, reputedly the richest man in America and the owner of the Astoria hotel in New York, was travelling in first class. His family fortune was estimated to be around $87 million ($2.26bn) today. He lost his life on the Titanic, leaving behind his wife Madeline, who was five months pregnant and survived.

First class: the super-rich passengers

Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Other famous names who were on board included Isidor and Ida Straus, the owners of Macy's department store. They both lost their lives in the disaster.

Second class: staterooms

Bedford Lemere & Co/Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

Those travelling in second class would have enjoyed facilities that were similar to first class on other liners. Most of the second-class cabins had bunk bed-style sleeping. This room pictured is from the RMS Olympic and would have been like the staterooms on the Titanic. These cabins were comfortable for the time and often had a writing desk or a small sofa as well as beds.

Second class: elevators

R Welch/Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

Like in first class, second-class passengers had access to elevators, like this one from the RMS Olympic. Although not as extravagant as those in first class where there were sofas to recline on, they still saved passengers the effort of having to climb the stairs between decks.

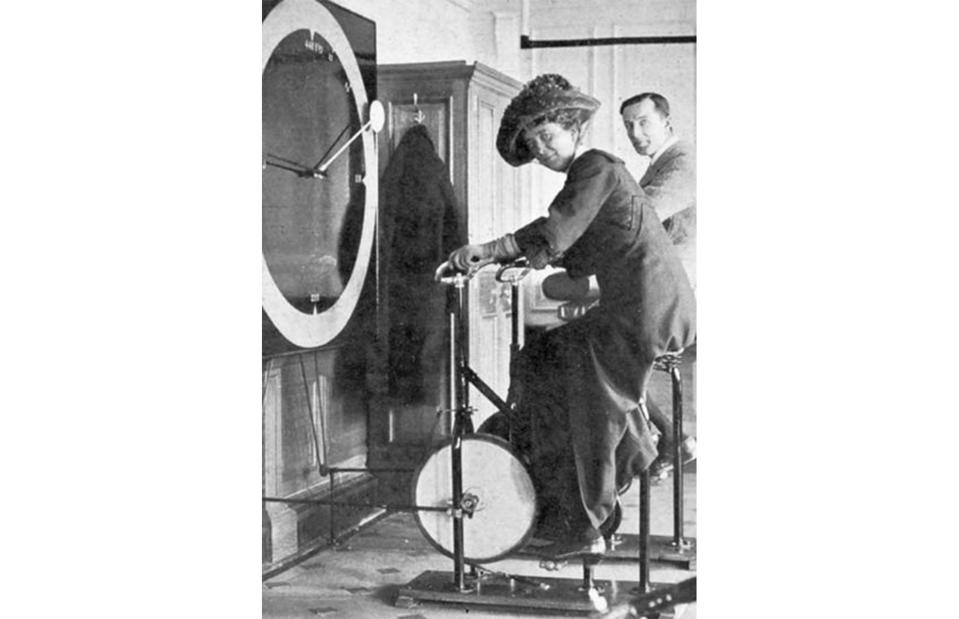

Second class: facilities

Central News And Illustrations Bureau/Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

Before she set sail, second-class guests had been allowed to tour the Titanic's first-class facilities. Pictured on the right is second-class passenger Lawrence Beesley, a science teacher from Dulwich College in south London who was impressed by the gym. However, no such luxuries were available for those travelling on a second-class ticket.

Second class: promenade deck chairs

Ralph White/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Second-class passengers did have access to three promenade areas where they could relax or take a stroll around the deck. Passengers could rent one of the ship’s wooden deck chairs for three shillings, or $1 per person for the whole voyage.

Steerage: staterooms

CHARLY TRIBALLEAU/AFP/Getty Images

Compared to other ships, life in steerage (third class) on the lower decks was comfortable for its time. Passengers often slept in four to six berth cabins which housed either families or single sex passengers. Single men and women were separated at opposite ends of the ship, with men at the bow and women at the stern. This replica shows the size of a four-berth cabin which might have been shared by strangers. Although there were lots of toilets available for steerage passengers, there were only two baths available – one for men and one for women.

Steerage: dining room

Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

The dining salon had white enamelled walls and tables were communal, meaning little privacy for passengers. Third class passengers weren’t offered a choice of menu, but they had freshly baked bread and fruit every day. It was a huge luxury when compared with other shipping lines, who usually made steerage passengers bring their own food. (Pictured is the dining room on the Olympic.)

Steerage: smoking room

Bedford Lemere & Co/Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

Third-class communal spaces had a simple, elegant feel. For example, this smoking room included wooden benches and chairs, plus a tiled floor. It's likely this image is from the Olympic.

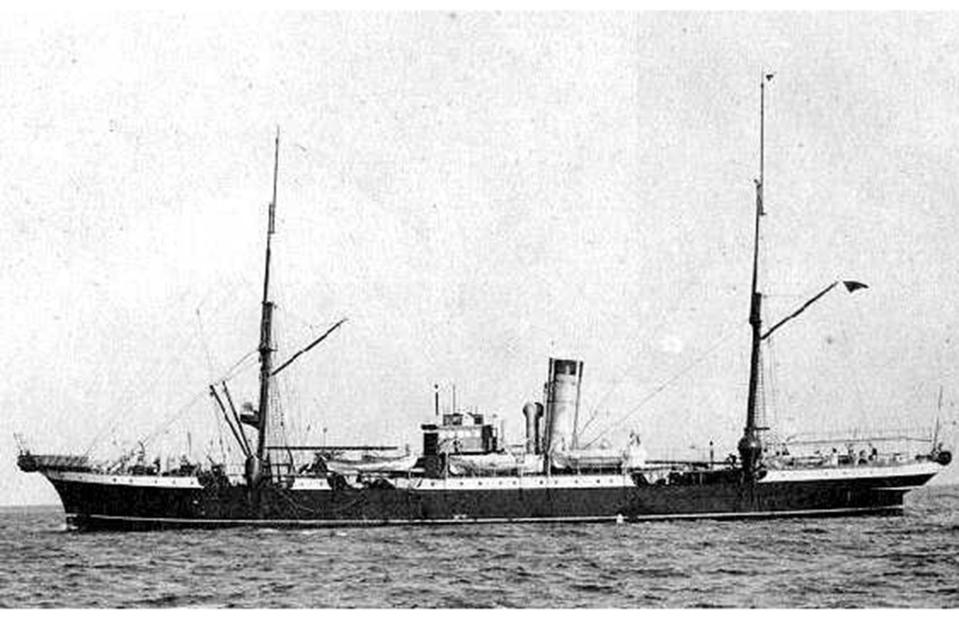

SS Mesaba sends a warning

GL Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

The steam-powered SS Mesaba had travelled in the same waters and sent a radio message warning of heavy pack ice and high number of large icebergs. However, the message was never relayed and the Titanic would eventually meet its fate later that night. The SS Mesaba sank in 1918 after a German torpedo attack during the First World War, but in October 2022 the shipwreck was finally located; multibeam sonar technology showed it had split into two parts in the Irish Sea.

"Iceberg right ahead"

Everett Historical/Shutterstock

Sadly all this opulence was destined to meet a watery end when, at 11.40pm on 14 April, the Titanic collided with an iceberg. Frederick Fleet, the Titanic's lookout, was one of the first to spot the iceberg, raising the alarm with the words "iceberg right ahead". Frederick was relying on his eyes only as the Titanic's binoculars were locked away in the crow's nest, the Titanic's lookout point.

Extreme peril

Print Collector/Getty Images

Captain Smith ordered the doors to the 16 watertight bulkheads to be shut. The Titanic could stay afloat if four of these compartments were full. But with over 100 feet (30m) of the ship opened up to the sea, six had flooded, including one of the boiler rooms. The walls of the compartments didn't extend far enough up the ship to prevent the water flooding into the next section. Within three hours of striking the iceberg, she had sunk.

To the lifeboats

Library of Congress/Public domain

There were just 20 lifeboats on board, enough for around 1,700 crew and passengers. Priority was given to women and children, with a much greater percentage of first-class passengers saved than those in steerage.

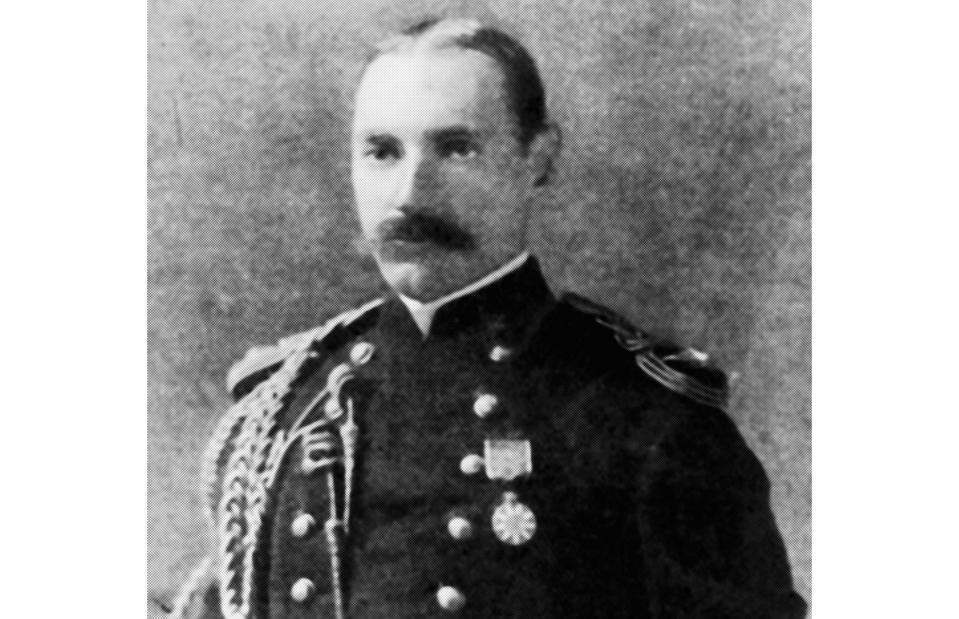

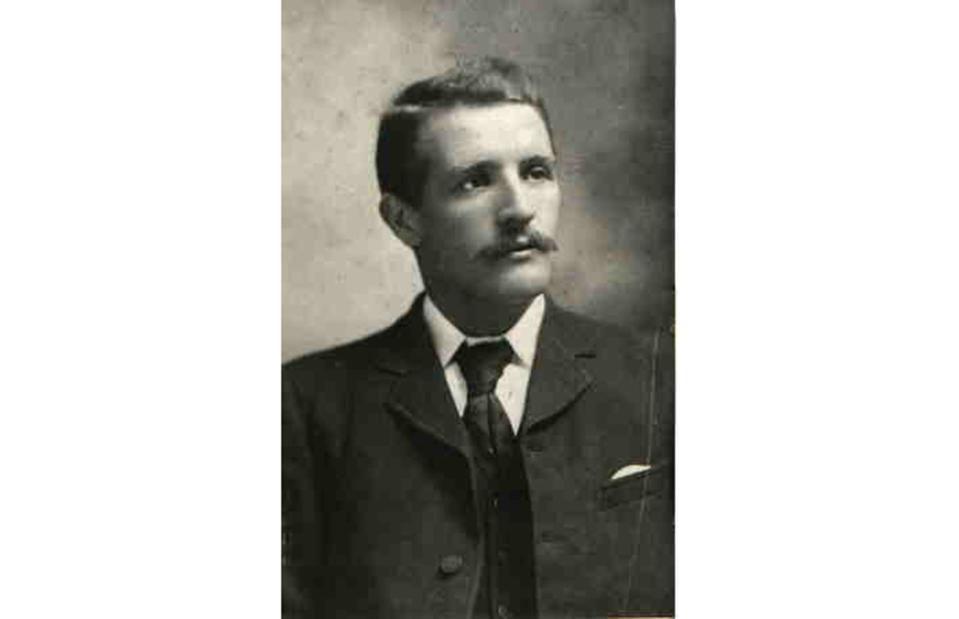

A hero

Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

First Officer William Murdoch was on the bridge (the area from which the ship was commanded) at the time the Titanic hit the iceberg and later that night he was put in charge of loading lifeboats on the starboard side. It has been suggested that more passengers disembarked on the starboard side as a result of Murdoch’s organised approach to lowering the lifeboats and the fact he let more men board. Perhaps he also understood the gravity of the situation, having witnessed the collision. Murdoch went down with the ship.

The final plunge

Bettmann/Getty Images

Those in the lifeboats would have witnessed the noisy horror of the ship sinking. As the front of the liner was pulled further into the water by the flooding, Titanic's stern was lifted further out of the sea. Eventually the hull of the ship snapped into two sections, between the third and the fourth funnels. The remaining part of the stern then gradually righted itself before flooding, pointing straight up out of the ocean and descending to the sea bed.

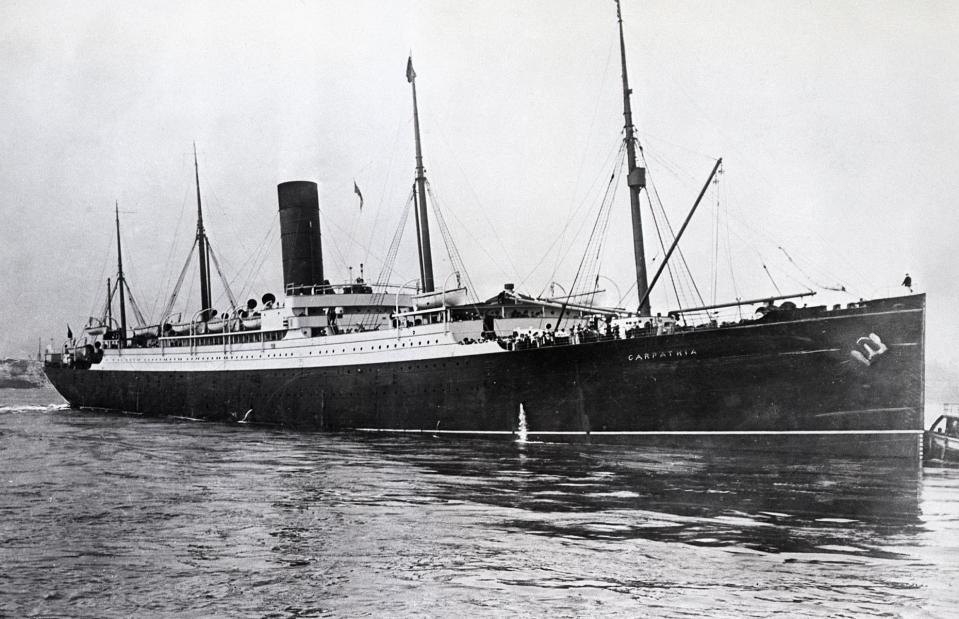

Carpathia to the rescue

Bettmann/Getty Images

While the Titanic had sent multiple distress signals it was Cunard's ship Carpathia which came to the rescue of survivors, taking them to New York. However, the Carpathia couldn't reach the scene until 4am, four hours and 20 minutes after the Titanic struck the iceberg. It took a further four hours to get survivors from the lifeboats onto the Carpathia. Six years later in July 1918, the unlucky Carpathia met her own terrible end too, sinking during the First World War after being torpedoed by a German U-boat.

Carpathia to the rescue

GL Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

Of the 20 lifeboats, four were collapsible Engelhardt lifeboats. These had a wooden base and canvas sides, but being less robust were harder to launch into the water. Collapsible Boat D was the last to leave from the port side of the ship and is pictured here approaching the Carpathia at dawn, flooded with icy seawater.

Survivors on the Carpathia

Library of Congress/Public domain

Because of the lack of up-to-date passenger and crew lists it's very difficult to say exactly how many died that night. Some crew members wouldn't have been recorded at all – a few certainly joined as last-minute replacements, stepping in for stokers who failed to show up. A US investigation found that 1,517 lives were lost while the British one claimed 1,503 died. It was the Titanic's crew who took the biggest hit: of 900 staff, 720 were from Southampton, England and only 124 returned. Overall there were just 706 survivors.

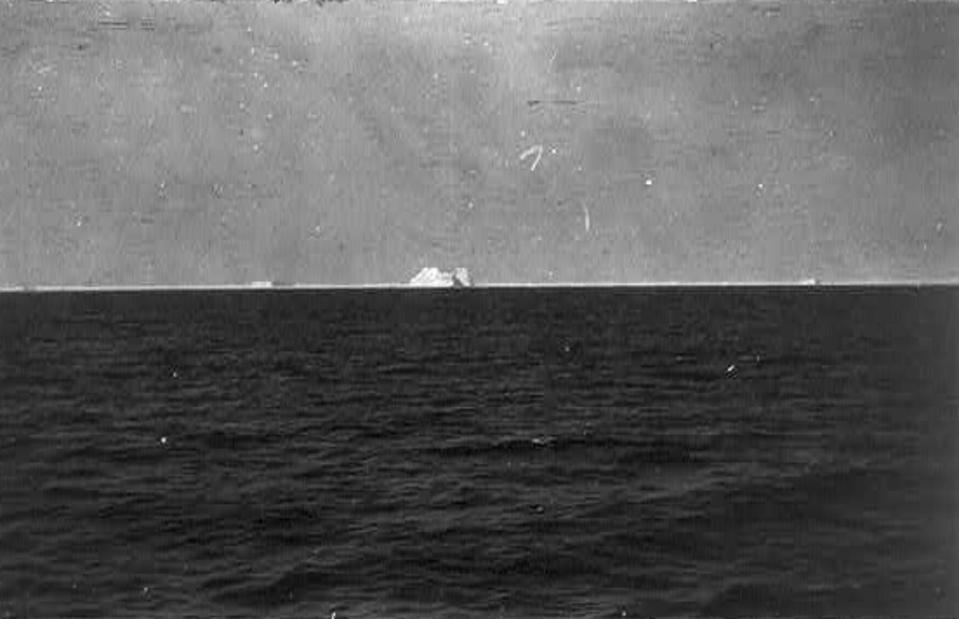

The iceberg that sank the Titanic?

Library of Congress/Public domain

This picture was taken from the Carpathia of the iceberg it's thought the Titanic struck. The Titanic was travelling through an ice pack that consisted of larger bergs such as the one pictured, and smaller formations called 'growlers'.

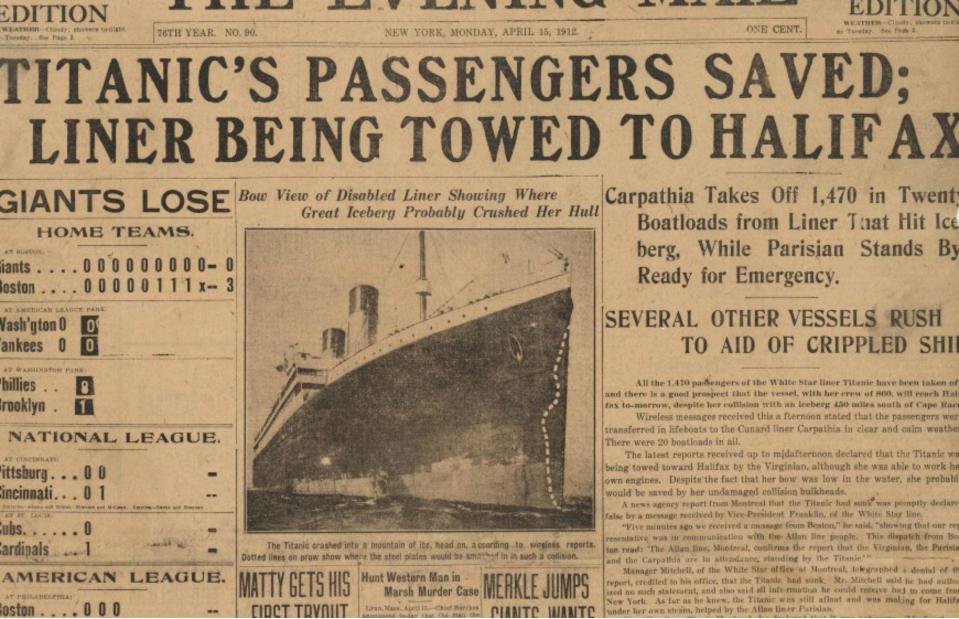

Everyone saved?

Courtesy NewseumED Washington DC

Several newspapers at the time reported the Titanic was safe and that all passengers were alive. The Times in the UK claimed the Titanic was being towed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada by the RMS Virginian on Tuesday 16 April 1912. The horrible truth wouldn't be fully reported until nearly 48 hours after the Titanic struck the iceberg.

The rescue ships

Unknown author/Public domain/via Wikimedia Commons

Four ships, including the CS Mackay-Bennett (pictured) were sent on a recovery mission on 17 April from Halifax. The ships collected both bodies and artefacts such as deckchairs. Over 100 of those who died are buried at Fairview Cemetery in the Nova Scotian city. There is also a highly informative exhibition at Halifax's Maritime Museum of the Atlantic that charts the city's role in the aftermath.

What happened to the crew?

Library of Congress/Public domain

Many survivors suffered from mental health issues for years after the sinking. Frederick Fleet, the Titanic's lookout, took his own life in January 1965, two weeks after his wife passed away. He was so poor he was buried in an unmarked grave.

Captain E.J Smith

Ralph White/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

The ship’s captain, Edward John Smith (pictured right), was one of White Star Line’s most experienced commanders and had served for over 40 years at sea at the time of the disaster. There have been mixed accounts of the Captain’s death, but it is believed that he refused to abandon the Titanic as it sank and went down with the ship. This image was taken by Father Francis Browne. An Irish Jesuit, he had been gifted a first-class ticket from Southampton to Queenstown by his uncle and took many of the last photographs of the Titanic's passengers, interiors and crew, which survived thanks to his early departure from the ship.

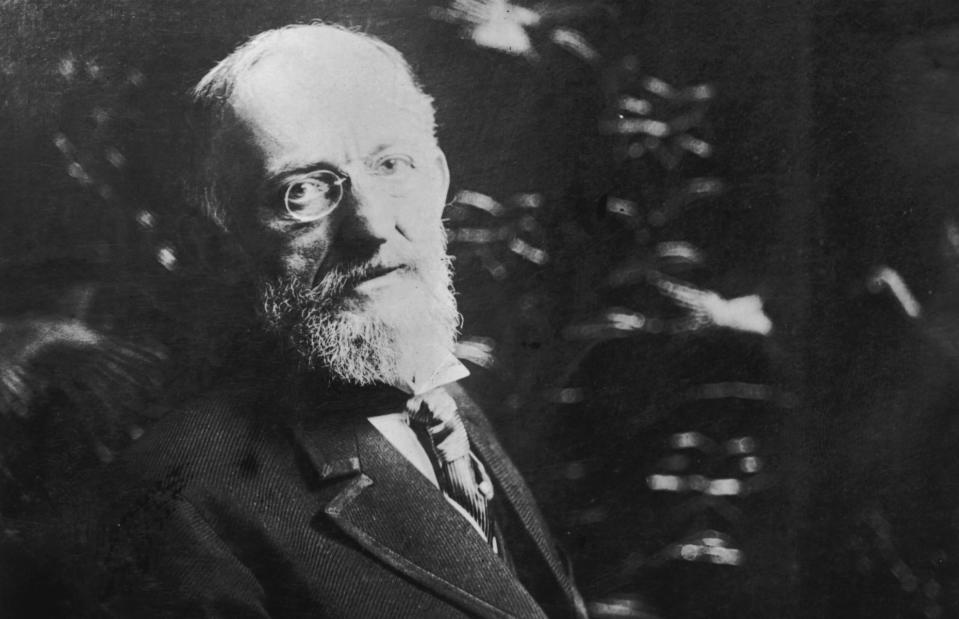

"The greatest coward in history"

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

White Star Line's chairman J Bruce Ismay was vilified by the press for getting in a lifeboat, with many considering he'd selfishly saved himself. Dubbed one of the "greatest cowards in history", he resigned from the White Star Line in 1913. He kept a relatively low profile afterwards, but did contribute to some significant seafaring charities. He died on 17 October 1937.

The inquiries

Bettmann/Contributor/Getty Images

The sinking of the Titanic prompted inquiries on both sides of the Atlantic. The US investigation highlighted that there was no lifeboat drill, which meant the lowering of vessels hadn’t been rehearsed and was haphazard. Most significantly, the two inquiries instigated a change in the rules: ships were required to have a lifeboat place for every passenger, changing safety at sea forever.

Raise the Titanic?

Keystone Press/Alamy Stock Photo

The story of the Titanic didn’t end with her sinking and the ship has been the subject of many films including 1958’s A Night to Remember and 1997’s Titanic. The 1980 movie Raise the Titanic, based on Clive Cussler’s bestselling book, is one of the most curious. The timing was unfortunate, as the film was made before the wreck was found and (spoiler alert) it depicts Titanic being raised from the seabed in one piece. The movie was an expensive flop, with the model of the Titanic, a tank to house it and the special effects costing millions of dollars that weren’t recouped at the box office.

Finding the ship

PA/PA Archive/PA Images

While the idea of finding the ship was first suggested in 1914 it wasn't until July 1986 that Robert Ballard (pictured centre with survivors Eva Hart and Bertram Dean) discovered the wreckage of the ship. He and his team had been photographing US submarines on a secret Cold War mission, and were allowed to search for the Titanic as a side project after the main job was done.

Exploring the wreck

WHOI Archives, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

In February 2023, never-before-seen footage of the Titanic's wreck was released to coincide with the 1997 blockbuster's 25th anniversary. The 80-minute video, shot in July 1986, reveals what the ship looks like as it sits under 12,400 feet (3,780m) of ocean: covered in seaweed, inhabited only by deep-water fish, but still unmistakably recognisable as the stricken liner from its portholes, railings, and once-opulent interiors.

Treasures from the seabed

AFP via Getty Images

Since the ship's discovery in 1986, there have been many research and discovery expeditions recovering around 6,000 artefacts. Director James Cameron’s team made 12 visits to the site in 1995 while filming Titanic. However, in August 2019 a deep dive to the site revealed that the wreck is starting to decay significantly. An agreement has now been signed that limits the number of licences to enter the wreck and remove artefacts, in the hope of preserving this poignant site for as long as possible.

Tragic search for Titanic wreck

American Photo Archive/Alamy

When OceanGate's Titan submersible descended to the depths of the North Atlantic, off the coast of Newfoundland in June 2023, another Titanic-related tragedy struck. The five-man crew were heading on an expedition to view the Titanic's wreck when the sub suffered a catastrophic implosion due to enormous water pressure, killing everyone on board immediately. The sub lost contact with the US Coast Guard one hour and 45 minutes into the dive, at 12,467 feet (3,800m) below sea level. When the sub failed to resurface on its scheduled ascent, a huge search mission was conducted to find the vessel and its passengers, which took four days. OceanGate has since suspended all exploration operations.

Titanic's lost sister

NomadicBelfast/Facebook

But it is possible to experience the Titanic’s magic first-hand today. The Titanic’s forgotten tiny sister ship, SS Nomadic, was used to ferry passengers and luggage to the doomed liner at Cherbourg, France. Now the tender has been restored and is open to visitors at her home in Hamilton Dock at Titanic Belfast, Northern Ireland. Designed and built by the same team as the Titanic, the Nomadic is the last White Star Line vessel in the world.

Suite dreams

The White Swan Hotel/Facebook

Many of the RMS Olympic's furnishings and fittings were almost exactly like the Titanic's and were sold when she was scrapped in 1935. Today you can still see some of the Olympic's interiors at the White Swan Hotel in Alnwick, England. Hardcore seafaring fans can even get married in the hotel's Olympic Suite.

No more replica

Sipa US/Alamy

An unfinished full-scale replica of Titanic sits rusting away in a dry dock in the landlocked state of Sichuan, China. Set to be a hotel and tourist attraction at Romandisea theme park, building work got under way in 2019. However, when construction was stopped during the pandemic, it was reported that the project had run out of money and there are no further updates on the project.

Titanic II

Blue Star Line

In April 2012, Australian mining billionaire Clive Palmer announced his plan to build Titanic II, a near-to-scale seaworthy reproduction at an estimated cost of £396 million ($500m). Currently there is no opening date for the project, but in March 2024, Palmer announced that plans were being finalised. He said: “We are very pleased to announce that after unforeseen global delays, we have reengaged with partners to bring the dream of Titanic ll to life. Let the journey begin."

Now discover jaw-dropping pictures of the world's most stunning shipwrecks