Ro Khanna Wants to Be the Future of the Democratic Party

Khanna, a congressman who represents Silicon Valley, sees himself as a bridge between America’s faded industrial might and its digital future.

Updated at 5:17 p.m. ET on April 3, 2024

In January, as the 2024 primary season got under way, Representative Ro Khanna stood in the middle of a spacious New Hampshire living room and marveled at the dozens of Democrats who had crammed in. “What enthusiasm for President Biden!” Khanna said as the crowd cheered. The California progressive wasn’t in the land of would-be presidents to promote himself—at least not directly. He came here to boost his party’s flagging 81-year-old incumbent.

Khanna represents Silicon Valley, but he’s lost count of how many times he’s been to New Hampshire; a local Democrat introduced him to the room as “the fifth member of our congressional delegation.” He told me he initially felt “sheepish” about coming back after he stumped here for Bernie Sanders four years ago, worried that people would assume he wanted to run for president. He’s gotten over that.

I spent a day driving across the state with Khanna as he made the case for Joe Biden as a write-in candidate. Before voters and the cameras, Khanna was a loyal surrogate, hailing Biden as a champion for the middle class, the climate, and abortion rights, while insisting that the president still has plenty of support. Back in the car, however, his worries and frustrations spilled out. Khanna is 47, three decades younger than the two men set to be on the ballot in November. He’s waiting—not altogether patiently—for the decks to clear, for the Biden and Sanders generation to finally retire. “We haven’t been driving a clear message,” Khanna told me. “We have to have a better message on the economy, and we have to have a better message on immigration.”

The proximate cause of Khanna’s distress was the bipartisan southern-border compromise that was then emerging from the Senate—and which, at the behest of former President Donald Trump, Republicans promptly killed. Khanna wasn’t a fan of the deal. He had wanted Biden to give a rousing speech about why immigration matters to America; instead, the president was about to give Republicans almost everything they wanted. “You’ve got no affirmative case,” Khanna told me. “There’s nothing. There’s a void.” What’s missing, he said, is “an aspirational vision.”

Here’s Khanna’s. He wants to marry the forward-looking spirit of the companies founded in and around his district—Google, Apple, Tesla—with the traditional middle-class values of his suburban upbringing in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. And he wants to inspire a “new economic patriotism” to rebuild America’s industrial base with climate-friendly technology—a project that he hopes will bring manufacturing jobs back to the Rust Belt, and working-class voters back to the Democratic Party.

A representative from America’s tech capital is an unlikely avatar of nostalgia, but Khanna speaks with as much longing for the country’s past, and his own, as any politician. He sees himself as a bridge between the nation’s faded industrial might and its digital future, appealing to a set of often-warring constituencies: progressives and pragmatists, tech capitalists and the working class, climate activists and coal country.

Khanna got his start in politics working for Barack Obama, who clearly serves as a model: a progressive who proposed transformative change without alienating too much of the country. The divide that Khanna wants to cross extends beyond the factions of the Democratic Party; it’s geographic, economic, cultural, technological, generational. And it’s wider than the one Obama faced. The nation that embraced the former president’s message is now even more polarized and dug-in.

Sometimes Khanna’s project seems naive, as though he’s trying to be everything to everybody at a time when nobody agrees on anything. But he believes that to defeat Trump and build a coalition that can survive beyond November, Democrats must offer an agenda that can excite the voters who have soured on the president and their party. Khanna wants to run for president on his vision one day—as soon as 2028—but his more urgent quest is trying to get his party to adopt it now. “Do I think I have a compelling economic vision for this country, for the party? Yes,” he said. “Do I mind if the president steals all of it? Absolutely not.”

If you recognize Khanna, you’ve probably seen him on cable news; he told me—and this was a point of pride—that he goes on Fox News more than nearly any other House Democrat. Early in his presidency, Biden was so impressed with Khanna’s cable appearances that he asked Ron Klain, his chief of staff at the time, to schedule more TV hits for Khanna. “Well, Mr. President,” Klain replied, “I think he does a pretty good job getting on TV all by himself.”

Khanna’s willingness to engage the right has gained him an audience that many Democrats have ignored—and the unofficial title of Congress’s “ambassador of Silicon Valley.” He frequently visits rural districts where GOP members of Congress seek investments from lucrative tech giants. (Khanna isn’t shy about getting tech executives on the phone. “I joke sometimes that I’m going to try to discover the limits of Ro’s Rolodex,” Representative Mike Gallagher, a Wisconsin Republican who serves with Khanna on the House select committee on China, told me.)

Khanna is also more willing than other progressives to work on legislation with Republicans, having co-sponsored bills with staunch Trump supporters and lawmakers who voted to overturn the 2020 election. Two months after the January 6 assault on the Capitol, Khanna appeared on Fox News alongside Representative Matt Gaetz of Florida and bragged about their legislation to reduce money in politics and end U.S. involvement in “forever wars.”

Khanna “has a risk tolerance that I think is rare for most members,” Gallagher, who is resigning from the House this month, told me. He recounted a meeting that he and Khanna had with Elon Musk last year, in which Khanna got the billionaire to host a live event with them on his social-media platform. “I’m not sure how many Democratic members would be able to do” that, Gallagher said. Or be willing to.

Khanna occupies an ideological space to the left of Biden but just to the right of progressives like Sanders and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, who identify as democratic socialists. He supports Medicare for All, tuition-free public college, and tax increases on high earners. But he also made plenty of money as a lawyer representing tech firms, and Khanna is not about to say that “billionaires should not exist,” as Sanders has. He defines himself as a “progressive capitalist,” and he believes progressives should frame wealth as a feature, not a bug, of the American system. “The progressive movement has to talk about a vision of production, a vision of wealth generation,” Khanna said.

The policy that best exemplifies this is Khanna’s push for federal investment in manufacturing technologies such as green steel and clean aluminum, which he sees as a way of reindustrializing the Rust Belt while minimizing carbon emissions and air pollution. After months of negotiations with environmental groups, labor unions, and manufacturers, Khanna is planning a trip later this spring to Johnstown, Pennsylvania, to unveil legislation that would spend billions to build steel plants in former industry hubs. (The bill will have at least one Republican co-sponsor from the region, he told me.) He thinks it will “capture the imagination”—a favorite Khanna-ism—of voters longing for America to reclaim its status from China as the world’s great manufacturer.

“We’re living in a time of big ideas, of big moments,” Khanna told me. “And I think we need a big vision to meet the times.” He’s worried, though, that Biden’s ambitions are only getting smaller. After two years of sweeping legislative accomplishments—a $1.9 trillion COVID-relief bill, $1.2 trillion for infrastructure, the most significant climate bill in American history—Biden has, in the face of a more hostile Congress, scaled back his domestic-policy goals. Among the objectives that the president dwelled on longest during his recent State of the Union address were fighting junk fees and restoring the number of chips in a snack bag—not exactly the stuff that captures imaginations.

No issue has tested Khanna’s ability to satisfy all of his party’s factions more than Israel’s military campaign in Gaza. Khanna called for a cease-fire seven weeks after the Hamas attack—much later than some of his progressive colleagues, and much earlier than Biden, who resisted that demand until last week, when the U.S. allowed a United Nations resolution backing a one-month cease-fire to pass.

Seven weeks was too long for many of Khanna’s supporters. One of his top political staffers resigned in protest in mid-October, and when demonstrators staged a sit-in at his office near the Capitol, one of Khanna’s interns joined them on the floor. By November, even his mother, Jyotsna, was getting on his case. “I wanted him to declare much sooner,” she told me.

Khanna is still not as critical of Israel as some on the left; he doesn’t describe its campaign in Gaza as “genocide” or “ethnic cleansing.” But as Palestinian casualties have increased, he’s called more forcefully for Biden to demand that the Netanyahu government halt its shelling of Gaza. “We have a lot of levers that we haven’t used,” Khanna told me.

In February, Khanna traveled to Michigan, trying to persuade the state’s large Arab American population to support Biden despite his own reservations about the president’s approach to Israel. A few days after Khanna’s visit, more than 100,000 Michigan Democrats—about 13 percent of the primary electorate—marked “uncommitted” on their ballot in protest of Biden’s Israel policy. Khanna urged the Biden campaign to take their message seriously. The party can’t afford to have the war still going on during the Democratic convention, he told me. “You’d have mass protests.”

The president’s advisers insist that the White House has no problem with Khanna’s critiques. They see him as exerting pressure in the right way—respectfully, not caustically—and serving as a conduit to younger, more progressive voters Biden needs to turn out in November. “The fact that Ro sees some issues differently than the president makes him an effective surrogate,” Klain told me. “That gives him credibility.”

Some progressives see Khanna differently, not as a bridge between generations but as an ambitious politician cozying up to power brokers. “He walks a fine line,” one official with a prominent left-leaning group told me on condition of anonymity to avoid criticizing an ally. For now, Khanna’s close ties with the Democratic establishment—Biden and Obama in particular—are politically useful. But soon, the official noted, many progressive voters will want a sharp break with the two men, and Khanna’s proximity to his party’s past could cost him.

Khanna wasn’t visiting early presidential-primary states solely to promote Biden. In between events in New Hampshire, Khanna met privately with leaders of the state’s largest labor union and a Democratic candidate for governor, people whose endorsements he might seek in a few years. Democratic activists alluded to his candidacy in 2028 as if it were a certainty. Khanna isn’t about to announce a campaign more than four years out—“Who knows what the future holds?” is his stock reply to questions about his plans—but he does nothing to dispel the assumptions that he’ll run.

When I asked party activists which Democrats they were excited to see more of after this election, some of them mentioned Khanna. More often, however, they cited bigger names with bigger jobs, such as Governors Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, Gavin Newsom of California, and Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania, as well as Vice President Kamala Harris and Pete Buttigieg, the transportation secretary. In New Hampshire, a few Democrats even mentioned Representative Hakeem Jeffries of New York, the House minority leader. As a compelling speaker, Khanna would hold his own on a primary-debate stage, but could he make it into the top tier of candidates?

Only James Garfield went directly from the House to the White House, and that was 143 years ago. But Khanna seems undeterred. As he often notes, his district contains some $10 trillion in market value, giving him a bigger platform than most representatives. “There are a lot of very, very high-profile House members that I think have an equivalent impact on the national debate as the Senate,” he said. “I think the rules of traditional politics have changed.”

Among many progressives, the heir to the movement Sanders created—and the dream presidential candidate—is AOC. “She occupies her own space,” says Joseph Geevarghese, the executive director of Our Revolution, the political group started by veterans of Sanders’s 2016 campaign. “Ro is not quite there yet, but he could be.”

As Khanna tries to make a national name for himself, voters will hear as much about Bucks County, Pennsylvania, as they do about California. Khanna remains nostalgic for the America that welcomed his parents from India in the 1970s. After graduating from the University of Michigan, his father became a chemical engineer and settled in Pennsylvania. Aside from two years in India, Khanna spent his childhood in a town about 45 minutes north of Philadelphia that offered him a quintessential middle-class upbringing—Little League baseball, Eagles football games, well-funded public schools. Khanna was one of just a few Indian American students in a large, almost entirely white high school, but he doesn’t remember experiencing any discrimination. “My faith in the country comes from here,” Khanna told me.

He insisted on giving me a tour of the county, now one of America’s most closely watched political bellwethers. His staff had arranged for him to speak at his alma mater, where he took an hour’s worth of questions from some of the school’s more politically informed students. They asked about steel manufacturing, the threat of China invading Taiwan, and how he reconciles his support for aid to Ukraine with his votes against defense spending. The exchanges were more substantive than many congressional hearings.

A couple of students pressed him on why the nation’s leaders, and in particular its two likely presidential nominees, were so old. “There’s a lot of frustration with the gerontocracy,” he acknowledged. “There’s a need for a new generation. I’m hopeful that will happen in the next cycle, that we will see very, very talented new voices emerge.”

None of the people I met in Bucks County who knew Khanna as a teenager was surprised that he’d ended up in Congress. Two of his teachers presented him with papers and clippings from his school days that they had kept for more than 30 years. We met Gretchen Raab, who taught Khanna’s ninth-grade English class, at a local diner, where she recalled thinking that he would become the first Indian American president. (Khanna seemed embarrassed by this disclosure, but only slightly.)

Khanna was civically engaged by the time he started high school, which he attributes at least partly to his family history. His maternal grandfather was active in Mahatma Gandhi’s independence movement, serving time in jail before becoming a member of the Indian Parliament. Khanna joined his school’s political-science club and once played then-Senator Joe Biden during a mock foreign-policy debate. His opposition to U.S. military adventurism started around this time: Raab raved about the op-ed that Khanna sent, as part of a class assignment in 1991, to the local newspaper arguing that President George H. W. Bush should not invade Iraq.

As an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, Khanna volunteered for the state-Senate campaign of a lecturer at the law school, a 35-year-old Democrat named Barack Obama. Several years later, when Khanna was contemplating his own first run for office in 2001, he emailed Obama, who advised him to avoid running in a big state. (Obama had just lost a congressional primary in Illinois.) Khanna ignored him and moved to California, where he challenged a 12-term incumbent in a 2004 House race. Like Obama, Khanna got crushed. He would go on to work for Obama’s administration before finally winning a seat in Congress on his third try, in 2016.

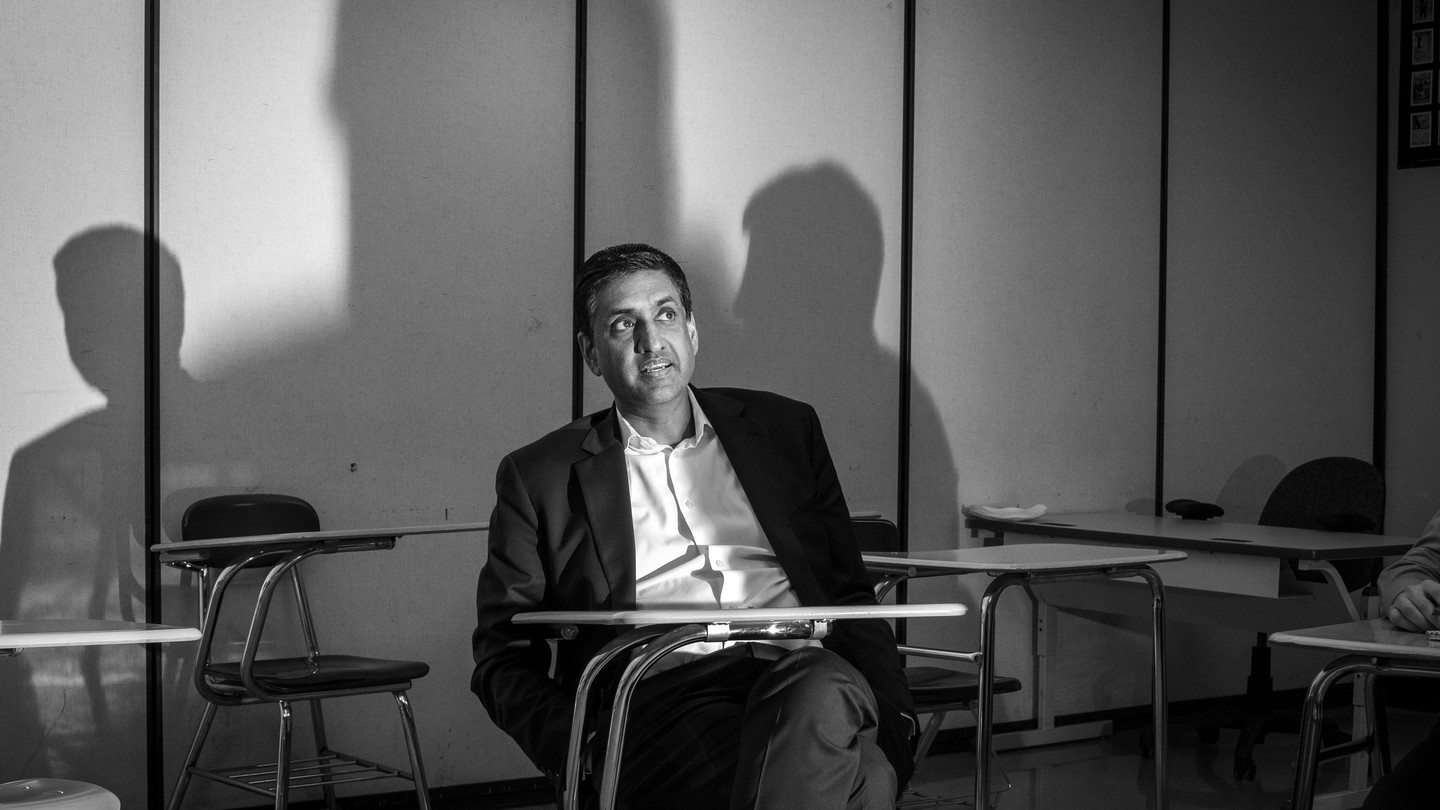

After Khanna finished talking with the students, he and I squeezed into desk chairs inside a small classroom and spoke with Derek Longo, one of Khanna’s history teachers. Longo described how a long-ago visit to the American cemetery in Normandy made him want to teach history. Khanna asked him what he thought about the rise of Trump.

Perhaps Khanna was expecting his teacher to talk about the threat Trump poses to democracy. Instead, he revealed something Khanna didn’t know: Longo voted twice for Trump. He praised Trump’s business background and told us that he worries about urban crime. In 2017, his daughter and son were struck by a driver under the influence of heroin as they were standing on a sidewalk in New Jersey. Longo’s son spent 10 days in intensive care, and his daughter, who was seven months pregnant, didn’t survive. Under state law, prosecutors couldn’t charge the driver with a double homicide because Longo’s granddaughter wasn’t born. The driver pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of vehicular homicide. He’s due to be released from prison next year.

The tragedy hardened Longo’s views on crime and abortion. “I could not vote for President Biden,” he said. Khanna sat quietly as Longo spoke. “One of the challenges we have as a country is we have a wrong stereotypical view of the Trump voter,” Khanna said to us after the conversation had moved on. “The Trump voter includes possibly the teacher you most respect.”

Longo spoke highly of Khanna, praising his slogan of “progressive capitalism” and his push to use technology to create economic opportunity. He even said he might be able to vote for Khanna one day. “A Trump-Khanna voter!” Khanna marveled.

That moment of exhilaration had faded by the time we got back to the car. Khanna conceded that Longo wouldn’t consider voting for him if he hadn’t been a former student. Yet he was exactly the kind of voter, Khanna said, that Democrats need to figure out how to reach—the Trump supporters who might respond to a progressive economic plan. That someone like Longo, so turned off by the Democrats now in power, will listen to his message—and even consider voting for him—seemed like an affirmation of Khanna’s vision. That he still wasn’t sold on his cherished former student, however, might be a sign of its limits.

This article previously misstated the amount of time that Derek Longo’s son spent in intensive care.