Nearly half the world’s population live in countries that will hold national elections this year, the largest such proportion in more than a century. But the big picture is complicated: “Over half of the 60 countries holding national elections this year are experiencing a democratic decline, risking the integrity of the electoral process…. The worsening election quality is concerning, given the pivotal role elections play,” warns the V-Dem Institute in a press release announcing its 2024 report, titled “Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot.”

Elections are “critical events,” the report explains, “that can either trigger democratization, enable autocratization, or aid stabilization of autocratic regimes”:

Surprise victories for a democratic opposition in critical elections can lead to the ousting of an incumbent, even in autocratic settings. The Maldives and Zambia are two recent examples of this.

Contrastingly, elections can also serve as powerful instruments of legitimation and spur further autocratization when challengers fail, such as in Hungary and Türkiye in recent times. The fact that a majority of elections during the “record election-year” 2024 take place in such contested spaces makes this year likely to be critical for the future of democracy in the world.

The extraordinary wave of 2024 elections, which encompasses seven of the world’s 10 largest countries — Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, Russia and the U.S. — along with other prominent nations such as Iran, Mexico, South Africa, South Korea and the U.K., comes as the erosion of democracy, or “autocratization,” in V-Dem’s language, continues in many different places.

Strikingly, the report includes two contrasting perspectives: a commentary from four investigators in the larger V-Dem Project argues that the current erosion of democracy “is fairly modest,” and calls for “a more measured tone,” while a special boxed section points in the opposite direction, highlighting a growing threat that V-Dem isn’t fully capable of measuring: the authoritarian-dominated BRICS bloc of nations, which allies the autocratic regimes of Russia, Iran and China with large Global South democracies such as Brazil and South Africa.

Other signs also hint at more troubling trends. Perhaps most notably, Israel has dropped from the ranks of liberal democracies for the first time in 50 years. That has nothing to do with the current war in Gaza or Israel’s treatment of Palestinians in the occupied West Bank, but primarily reflects “substantial declines in the indicators measuring the transparency and predictability of the law, and government attacks on the judiciary.”

Arguably, V-Dem has no measures that capture Israel’s deepest democratic flaws. “We can only speak to issues [on] which V-Dem has data, hence not on topics such as toxic ethno-nationalism,” V-Dem Institute director Staffan Lindberg, lead author of the report, said via email. “While we provide the most comprehensive database on democracy in the world, there are indeed areas we do not cover.”

While the U.S. persists in depicting itself as the global avatar of democracy, its support for Israel’s war in Gaza puts it at odds with the vast majority of the world, and undermines support for the war effort in Ukraine as well as the case for democracy more broadly. While our collective ability to make sense of autocratization and democratization continues to advance, the questions keep piling up even faster. As you may have noticed, we live in a time of chaotic flux.

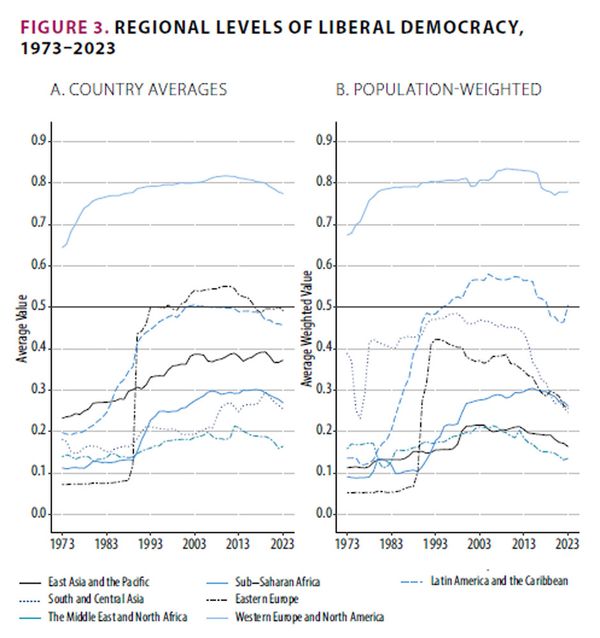

Overall, according to V-Dem’s report, the share of world population living in “autocratizing” countries has overshadowed the share living in democratizing countries since 2009, with the starkest declines seen in Eastern Europe, South Asia and Central Asia. Latin America and the Caribbean go “against the global trend,” the report finds: “Democracy levels increase, and large countries are more democratic than smaller ones.” There are some indications that “the autocratization wave is slowing down,” but that is far from a clear verdict.

Deeper forces, longer patterns

This history-shaping year of elections could have significant effects — but in what direction? Only three of this year’s major elections are in democratizing countries, while 31 occur in more autocratic contexts. Furthermore, underlying forces that are difficult to define will play a significant role. In 2021, Max Fisher analyzed V-Dem data for a New York Times feature, and found that the U.S. and its allies were responsible for a large share of democratic backsliding that occurred in the 2010s (36%), while their contribution to democratization was a meager 5%.

While the U.S. persists in depicting itself as the global avatar of democracy, its support for Israel’s war in Gaza puts it at odds with the vast majority of the world, and undermines support for the war effort in Ukraine and the case for democracy more broadly.

The picture was very different after the end of the Cold War. There was a broad trend of democratization in the 1990s, largely resulting from relaxed great-power backing for autocratic allies, both in the former Soviet bloc and in regions where the U.S. had “backed or installed dictators, encouraged violent repression of left-wing elements, and sponsored anti-democratic armed groups,” as Fisher wrote. After 9/11, however, the U.S. revived it’s longtime support for autocratic allies, particularly in the Islamic world.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, Fisher found that U.S. policy had a stronger impact on autocratization than any policies enacted by the authoritarian governments in Russia and China, “whose neighbors and partners have seen their scores change very little.”

These contradictions of American policy are part of a larger pattern, as described in the recent book “The Deep Roots of Modern Democracy” (Salon interview here). While liberal democracies remain dominant in Western Europe, that dominance rests partly on ethnocentric foundations that are ultimately at odds with the values such democracies claim to support. History suggests, in fact, that Euro-American liberal democracies have played a significant role in retarding democratic progress elsewhere. Their interest in “stability,” free trade and military alliance have taken precedence over a rhetorical commitment to democracy.

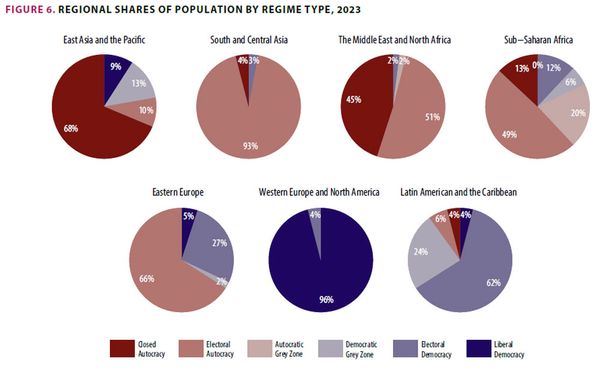

Using its fourfold “Regimes of the World” categories — liberal and electoral democracies on one hand, electoral and closed autocracies on the other — V-Dem finds the world “almost evenly divided between 91 democracies and 88 autocracies,” with a severe population imbalance: More than 71% of the world’s population, or 5.7 billion people, live in autocracies, a dramatic increase from 48% 10 years ago. Only 29% of the global population (2.3 billion people) live in liberal or electoral democracies.

“The level of democracy enjoyed by the average person in the world in 2023 is down to 1985 levels,” V-Dem reports. ; by country-based averages, it is back to 1998,” V-Dem reports. Nearly all of what the institute defines as “components of democracy” are getting worse in more places than they’re getting better, and three of those components stand out: “freedom of expression” has gotten worse in 35 countries; “clean elections” are deteriorating in 23 countries (but improving in 12); and “freedom of association” is more restricted in 20 countries (and expanded in just three).

“Autocratization,” V-Dem finds, is ongoing or accelerating in 42 countries that are home to 35% of the world’s population — but India, now the most populous country in the world, accounts for half of that 2.8 billion total. Of those 42 nations, 28 were previously considered democracies, “illustrating that democratization processes are fragile and are often reverted,” as the report notes. One common theme is that free and fair elections are increasingly being undermined around the world; the autonomy of election management boards is weakening in 22 of the 42 autocratizing countries.

Democratization trends are much weaker, the report finds: While that process is found in 18 countries, they account for just 5% of the world's population, and the majority of them, roughly 216 million people, live in Brazil. The nine nations V-Dem considers “stand-alone” democratizers (rather than autocratizing countries making “U-turns”) represent just 30 million people, less than 0.4 percent of the global population. Several are tiny island states, such as Fiji, the Seychelles, the Solomon Islands and Timor-Leste; the largest such country is the Dominican Republic, with 11 million citizens.

More than 71% of the world’s population, or 5.7 billion people, live in autocracies, a dramatic increase from 48% 10 years ago. Only 29% of the global population lives in liberal or electoral democracies.

V-Dem also finds that 25 countries are “near misses” of autocratization, while nine are “near misses” of democratization. So both categories could increase once this history-shaping election year provides a clearer picture — or doesn’t. We’ve already seen various post-election chaos in countries both large and small, including Argentina, Pakistan and the Netherlands, where a far-right party won the most seats in a Nov. 22 election but has been unable to forge a coalition government.

But even the recent sham election in Russia — which took place after the death in prison of Alexei Navalny, the only plausible threat to Vladimir Putin — provided an opportunity for organized protest, which is normally impossible, via the “noon against Putin” initiative. That could be just a ripple without consequences, as Putin tried to portray it, but years from now it could also stand out as an unlikely turning point — a worldwide pro-democracy protest (since it included overseas Russian embassies) when no such thing seemed possible. V-Dem has no way to capture or measure such things.

As noted above, there’s a tension in the report itself that heightens the uncertainty. The commentary from four investigators arguing that democratic decline is “fairly modest” focuses most heavily on V-Dem’s partial reliance on population-based measures. India’s disproportionate impact is their main concern. Yet the report also contains information pointing in the opposite direction — most notably the expanding influence of the so-called BRICS+ bloc of nations, comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and a growing list of smaller allies.

The BRICS challenge

The boxed section entitled "BRICS Expansion and the Future of Global Democracy" notes that the growing power of these developing nations “sends a message about a shifting balance of global power and an emergence of a multipolar world, and that the weakening relative power of democracies “also poses questions about prospects for human rights and democratic freedoms around the world.”

For generations, a comforting narrative has assured us that expanding global trade will lead inevitably to increasingly open and democratic societies and an era of international peace. That was Richard Nixon’s original rationale in going to China, and the impetus behind the “free trade” push of the 1990s. But the BRICS+ group’s “total share of global real GDP has more than tripled during the last 30 years,” while the G7 nations’ “share of world real GDP has shrunk from 68% in 1993 to 44% in 2023”:

The relative success of BRICS is all the more remarkable when taking into account that ideologically different autocracies China and Russia and now electoral autocracy India managed to work pragmatically together with still democratic Brazil and South Africa for many years. Even the Sino-Indian border dispute, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the following sanctions did not break up the block.

V-Dem’s liberal democracy index, or LDI, reveals stark differences between the G7 and BRICS+. (That index measures rule of law, checks and balances, civil liberties, free and fair elections and a free and independent media.) Within BRICS. Brazil and South Africa represent relatively democratic systems, while Russia and China are the world’s leading autocracies, which also describes recent additions such as Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. India, by the way, slipped from V-Dem’s “electoral democracy” category to “electoral autocracy” two years ago, and its LDI score has fallen by almost half in the last decade.

We need your help to stay independent

Brazil presents an opposed example, as the world’s largest democratizing country. It could have gone the other way, had former President Jair Bolsonaro won re-election. But Lula’s 2022 victory and the unified rejection of Bolsonaro’s attempted insurrection — strikingly different from what happened in America — can be seen as a "critical event" that affected the country’s political system as a whole.

The report’s boxed section on Brazil notes the importance of such events in halting or reversing autocratization, and highlights specific factors in that process. That began before the election, when Brazil’s electoral management body actively sought to counter disinformation and misinformation “and to disavow fake news about the electoral process.” The Brazilian courts investigated “digital militias,” meaning “online criminal groups that work against democracy and the democratic state.” There was a broad pro-democracy alliance of opposition parties; Lula’s running mate was a political centrist who had been “his political adversary for decades.”

Brazil’s system successfully resisted Bolsonaro’s attempts to change the rules in his favor, aided by diplomatic support from the U.S., Britain, France and Germany. International observers agreed the election was free and fair and rapidly recognized Lula’s victory. Legislators, law enforcement officials and the Brazilian Supreme Court all accepted the results and rejected Bolsonaro’s claims of fraud. And despite Bolsonaro’s leading comments in praise of Brazil’s former military dictatorship, the troops stayed in their barracks and made no moves toward a coup. More recently, Bolsonaro was convicted on charges of abusing his power as president, and is now ineligible to seek or hold public office until 2030.

Brazil's example suggests that the pathway to reversing autocratization and restoring democracy is clear. Having the will and capacity to follow that path is quite another matter.

That example suggests that the pathway to reversing autocratization and restoring democracy is clear, although having the will and capacity to follow that path is another matter altogether. Donald Trump, as we know, has not been barred from running again, even after Jan. 6. Indeed, the Supreme Court basically rewrote the 14th Amendment to make sure he could run. Beyond that, the U.S. lacks some of the central institutions that Brazil drew on, such as the electoral management body and a federal court system with investigative powers. But the criticial need to consolidate a broad pro-democracy alliance faces no such barrier. What stands in the way is mostly the perversity of our political system, which helped empower Trump in the first place.

Decoding the global state of democracy

The challenge on the world stage is considerably more difficult. As noted above, democratic decline has been the dominant trend since 2009, most starkly in Eastern Europe, South Asia and Central Asia, with Latin America and the Caribbean going the other way. A historical comparison between those regions is illuminating, as shown in this chart tracking changes from 1973 through 2023.

Graphic from "Democracy Report 2024: Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot" (Courtesy of University of Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute)Both regions were strikingly similar in the early ‘90s, but by 2023, they had steadily diverged. Another chart in the report show each region by percentage of regime type, which makes their current condition strikingly distinct: Latin America and the Caribbean are largely democratic (gray zone or better), while Eastern Europe is 66% electoral autocracy. So the question is why and how that happened.

Graphic from "Democracy Report 2024: Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot" (Courtesy of University of Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute)Both regions were strikingly similar in the early ‘90s, but by 2023, they had steadily diverged. Another chart in the report show each region by percentage of regime type, which makes their current condition strikingly distinct: Latin America and the Caribbean are largely democratic (gray zone or better), while Eastern Europe is 66% electoral autocracy. So the question is why and how that happened.

Graphic from "Democracy Report 2024: Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot" (Courtesy of University of Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute)A partial answer is suggested by the argument laid out in “The Deep Roots of Modern Democracy,” which holds that port cities and access to global trade routes are crucial ingredients. Eastern Europe is largely landlocked, and therefore would logically have a harder time building strong modern democracies, compared to the oceanfront regions of Latin America and the Caribbean.

Graphic from "Democracy Report 2024: Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot" (Courtesy of University of Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute)A partial answer is suggested by the argument laid out in “The Deep Roots of Modern Democracy,” which holds that port cities and access to global trade routes are crucial ingredients. Eastern Europe is largely landlocked, and therefore would logically have a harder time building strong modern democracies, compared to the oceanfront regions of Latin America and the Caribbean.

That also helps explain why Western Europe and North America are the only world regions almost entirely governed by liberal democracies, and why they haven’t spread as inevitably as ideologues of the “End of History” era once suggested. In effect, Europe and the U.S. have been a negative influence overall, due to economic imperialism and military intervention, which have done more to prop up elite rule in many places than to spread democratic values and practices.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Representative democracy is primarily a means of national elite coordination and conflict, subject to broad popular constraints. Its organized influence varies considerably over time as well as between countries. In most of Western Europe that influence helped create robust welfare states, something that never quite happened in the U.S. The American and European elites who drive foreign policy have inherited deep assumptions and orientations drawn from the era of colonialism and imperialism, even as overtly racist or nationalist assumptions have been rejected.

While the U.S. generally claims to value democracy as an abstract goal, our government does not actually pursue that goal in any meaningful or consistent fashion. We have something like 750 military bases around the world as of 2020, but nothing remotely comparable devoted to spreading democracy. Most Americans take that for granted as our nation’s way of being in the world, which supposedly has something to do with spreading freedom and democracy. That’s not how most of the world sees America, or what our lopsided defense budget says. Over and over again, it’s not what America’s global actions actually produce.

V-Dem’s data can’t cover everything, as Lindberg acknowledged. But it does provide a wealth of guidance about specific aspects of democracy that can be improved. If Americans were as seriously committed to democracy as we like to believe, perhaps we would restructure our national priorities accordingly.

Read more

about the tortured state of democracy

Shares