The Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History in D.C. is celebrating a significant milestone for one of its oldest fossils, known as Allosaurus.

In layman’s terms, the skeleton is considered to be the best anywhere in the world.

The new status was bestowed by members of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). The Smithsonian’s Curator of Dinosauria said this is a coveted scientific honor that took almost 15 years to obtain.

“In 2010, a petition was made to the ICZN to solve the problem that the very famous and scientifically important dinosaur A. fragilis was based on materials that couldn’t really be identified as anything more than a non-descript predatory dinosaur,” Carrano said.

“This decision really emphasizes how important our specimen is — both historically and in the present — for dinosaur science.”

During the Late Jurassic Period more than 150 million years ago, the Allosaurus terrorized other dinosaurs. Stretching 20 feet tall and having a mouthful of dagger-like teeth, the prehistoric predator roamed North America with species of that era including the armored Stegosaurus and a number of supersized sauropod dinosaurs like Diplodocus.

The fossil’s journey from its initial discovery in a Colorado quarry to its esteemed place at the Smithsonian is a 150-year story, just a fraction of the time, when considering its age, seeing that it roamed earth millions of years ago.

In 1884, a colleague of renowned Yale University paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh uncovered a nearly complete Allosaurus skeleton, and the remains were shipped back to Marsh, but he was not able to conduct a detailed examination of the fossil before dying in 1899.

Years later, Marsh’s fossils were shipped to the Smithsonian’s United States National Museum, the precursor to today’s National Museum of Natural History. Then in 1920, the museum’s paleontologist Charles Gilmore and his staff unpacked the treasure trove of fossils, which included the rare, nearly fully intact Allosaurus specimen from Colorado.

Gilmore’s painstaking and groundbreaking work made this specimen and the Smithsonian’s overall collection, an essential piece of the Allosaurus puzzle.

“Gilmore’s paper has remained an important reference for paleontologists and really established our specimen as a sort of ‘flagship’ individual for Allosaurus,” Carrano said. He is currently updating Gilmore’s nearly-125-year-old description of USNM V 4734. “As a result, our specimen has functioned as a sort of de facto type.”

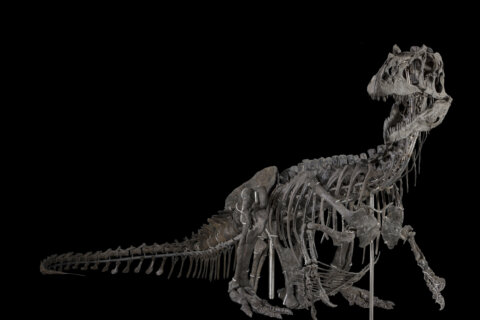

Museum visitors are able to see the historic Allosaurus specimen displayed in the museum’s Deep Time fossil hall along with the type specimen of its fossil foe, Stegosaurus, and the sauropods Diplodocus and Camarasaurus. The exhibition’s Allosaurus mount, which contains the animal’s real fossilized bones, displays the dinosaur in a rarely seen position.

Instead of chasing down prey, the Allosaurus’ skeleton is crouched down like a modern bird as it guards a clutch of fossilized eggs.

“USNM V 4734 has always been a prize of the Smithsonian’s dinosaur collection,” Carrano said. “Now it has a prominent position in the Deep Time Hall, reflecting aspects of its biology that were unimagined in Marsh or Gilmore’s times.”

In an effort to make the display as realistic as possible, the Allosaurus is displayed in the hall alongside its longtime foes the Stegosaurus, and the sauropods Diplodocus and Camarasaurus.

The fossilized bones of the Allosaurus are in a rarely seen position. Instead of chasing its prey, the skeleton is crouched down like a modern bird, guarding a clutch of fossilized eggs.

The museum this summer is celebrating its fifth-year anniversary of the “David H. Koch Hall of Fossils — Deep Time,” containing 700 fossil specimens.

Opened since 1910, the National Museum of Natural History contains the world’s most extensive collection of natural history specimens and human artifacts. It is open daily, except Dec. 25, from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Admission is free. For more information, visit the museum on its website, blog, Facebook, X and Instagram.

Get breaking news and daily headlines delivered to your email inbox by signing up here.

© 2024 WTOP. All Rights Reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.