Sextortion

Scammers are targeting teenage boys on social media—and driving some to suicide.

One word from a stranger on social media was all it took. “Hey,” she said.

Jordan DeMay read the Instagram message at 10:19 p.m. on a Thursday night in March 2022. He had just kissed his girlfriend goodnight and was on his way home to pack: The next day he was escaping Michigan’s frozen Upper Peninsula for spring break in Florida.

“Who is you?” he responded.

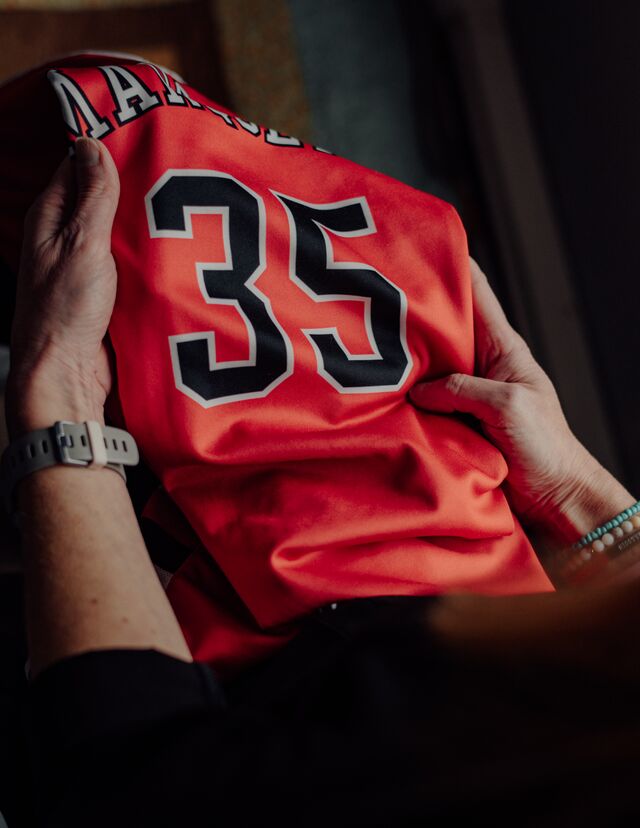

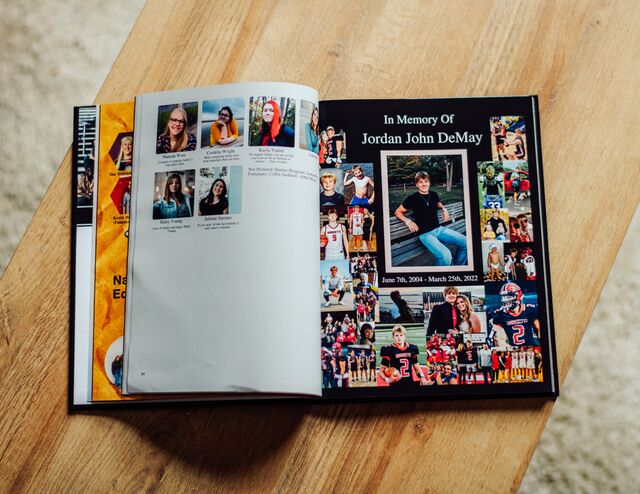

Tall, athletic and blond, Jordan was a football and basketball star at Marquette Senior High School, as well as its homecoming king. The 17-year-old often received friend requests from random girls on social media. He liked the attention.

This one came from Dani Robertts. Her profile photo showed a teenager with a cute smile, sunglasses perched atop shiny brown hair, hugging a German shepherd. Dani told Jordan she was from Texas but was going to high school in Georgia. They had one mutual friend and started texting about school life while he did his laundry.

Around midnight, Dani got flirtatious. She told Jordan she liked “playing sexy games.” Then she sent him a naked photo and asked for one in return, a “sexy pic” with his face in it. Jordan walked down the hallway to the bathroom, pulled down his pants and took a selfie in the mirror. He hit send.

In an instant, the flirty teenage girl disappeared.

“I have screenshot all your followers and tags and can send this nudes to everyone and also send your nudes to your family and friends until it goes viral,” Dani wrote. “All you have to do is cooperate with me and I won’t expose you.”

Minutes later: “I got all I need rn to make your life miserable dude.”

Jordan’s tormentor knew his high school, his football team, his parents’ names, his address. Dani had created photo collages of his family and friends and plastered his nude picture in the middle. One screenshot had his nude selfie in a direct message addressed to his girlfriend. Dani said Jordan had 10 seconds to pay, or the message would be sent.

“How much?” Jordan responded.

The price was $300. He transferred the money via Apple Cash and pleaded to be left alone. But it wasn’t enough. Now Dani wanted $800. Jordan sent a screenshot of his bank account showing a balance of $55, offering to send everything he had.

“No deal,” Dani replied.

By 3 a.m., Jordan was starting to unravel.

Jordan:Why are you doing this to me?

I am begging for my own life.

Dani:10 … 9 … 8 …

I bet your GF will leave you for some other dude.

Jordan:I will be dead.

Like I want to KMS [kill myself]

Dani:Sure. I will watch you die a miserable death.

Jordan:It’s over. You win bro ….

I am kms rn. Bc of you.

Dani:Good. Do that fast.

Or I’ll make you do it.

I swear to God.

It was early 2022 when analysts at the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) noticed a frightening pattern. The US nonprofit has fielded online-exploitation cybertips since 1998, but it had never seen anything like this.

Hundreds of tips began flooding in from across the country, bucking the trend of typical exploitation cases. Usually, older male predators spend months grooming young girls into sending nude photos for their own sexual gratification. But in these new reports, teen boys were being catfished by individuals pretending to be teen girls—and they were sending the nude photos first. The extortion was rapid-fire, sometimes occurring within hours. And it wasn’t sexually motivated; the predators wanted money. The tips were coming from dozens of states, yet the blackmailers were all saying the same thing:

“I’m going to ruin your life.”

“I’m going to make it go viral.”

“Answer me quickly. Time is ticking.”

“I have what I need to destroy your life.”

In January 2022 the center received 100 reports of financially motivated sexual extortion. In February it was 173. By March, 259. The numbers were trending up so quickly and the script was so similar that the analysts reported it directly to Lauren Coffren, the executive director of the center’s exploited children division. “The bad actors were so fast and so ruthless,” Coffren says. Last year, after the center asked social media platforms to start tracking the crime, NCMEC received more than 20,000 such reports.

Sextortion Cases

Monthly reports of sextortion made to NCMEC

The scam, which the FBI calls sextortion, has become one of the fastest-growing crimes targeting children in the US, according to the agency. In an 18-month period ending in March 2023, the FBI says, at least 20 minors, primarily boys, killed themselves after falling victim to the scam. (Seven more sextortion-related suicides have been reported since then, the latest in January.) The crime is “just out of control,” says Mark Civiletto, a supervisory special agent in the FBI’s Lansing, Michigan, office. “This is something that’s touching every neighborhood across the country.”

The FBI, Civiletto says, is used to handling online fraud cases, such as romance scams or elder abuse, which require a long runway so the perpetrator can build rapport with their victims. Sextortion can be done in minutes. Scammers have zeroed in on a faster method, Civiletto says, one that returns a higher payout by exploiting the shame and embarrassment of teenage boys. And social media has given scammers a direct line to American teens. With the swipe of a thumb, criminals can see a scrapbook of these kids’ lives, including the names of their friends and family members.

Last year a Snap Inc. survey of more than 6,000 young social media users in six countries including the US found that almost half said they had been targeted in an online sextortion scheme. One-third of those said they had shared an intimate photo.

The scammers have been bold enough to publish playbooks for how to commit this type of blackmail via TikTok and YouTube, in clear violation of social media platforms’ community guidelines. Both companies said in written statements that they had removed posts related to this scam that have been brought to their attention and vowed to continue to take down such content. But a search on both platforms found similar content is still available.

In late January the chief executive officers of the world’s biggest platforms, including Meta, Snap and TikTok, were grilled during a congressional hearing about how their companies have endangered a generation of children. There were questions about addictive algorithms and youth suicide rates—and the sudden rise of sextortion.

At one point in the hearing, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta Platforms Inc., which owns Instagram, was asked to say something to the dozens of bereaved parents sitting in the gallery, holding photos of their dead children. “I’m sorry for everything you have all been through,” he said.

The 911 call blared over the sheriff’s office radio in the picturesque lakeside city of Marquette at 7:40 a.m. on a Friday morning: “17-year-old suicide, gunshot.” Detectives Lowell Larson and Jason Hart caught each other’s eye. Suicides in the area were rare; the sheriff’s office had responded to only three the previous year. Teen suicides were even rarer. They ran to an unmarked Chevy Tahoe, leaving two steaming coffee cups behind. The sun was just beginning to rise over Lake Superior.

The detectives arrived at the scene within minutes. John DeMay, a former police officer who went to school with Larson, was standing in the doorway of his beige split-level house, wide-eyed and wearing a T-shirt despite the below-freezing temperature. “My son … ” he started. “It’s OK, John,” Larson said, placing a hand on his shoulder. Hart guided DeMay upstairs, and Larson walked toward Jordan’s bedroom.

He took a deep breath and stepped inside. Jordan was sitting upright in his bed, leaning against a blood-spattered wall. His left arm hung from the mattress, and his right hand held a pistol. His cellphone was in his lap, the screen lighting up with messages.

Larson photographed the scene. He pulled on a pair of black nitrile gloves before picking up Jordan’s phone, switching it to airplane mode and sliding it into a paper bag. He also bagged the gun, which belonged to Jordan’s father, and the cartridges, entering it all into the case file.

The “what” of the case was already clear, Larson recalls two years later from behind his desk at the sheriff’s office, raccoon and beaver hides splayed on a wall behind him. It was the “why” that was disturbing him.

Looking around Jordan’s messy bedroom that morning, Larson didn’t see a suicide note. Jordan had no history of unhappiness or mental illness. His bag was packed with swimsuits and sunscreen, ready for Florida. The alarm on his phone kept going off. Everything Larson could see indicated that when Jordan got into bed, he intended to wake up.

Kyla Palomaki was in class but couldn’t concentrate. Text messages to her boyfriend weren’t going through. She kept rereading Jordan’s last cryptic message, sent at 3:30 a.m.: “Kyla, I love you so much. I made a mistake and wish I could continue but I can’t do this anymore. This was a choice I made and I must pay myself.”

Jordan had left her house at about 10 the night before. What mistake could he possibly have made in the early morning hours? He hadn’t replied to three phone calls and eight text messages, including her last one that just said “JORDAN!” The only message she’d received about Jordan that morning was from his mom, Jennifer Buta, asking whether he was in school—which seemed odd.

She was sitting in her second-period class, watching a movie she couldn’t care less about. Kyla, an A student who goes to church every Sunday, was instead staring at her phone, willing Jordan to reply. She recalls that at this point her unease was giving way to fear.

When the school administrator knocked on the classroom door, Kyla prayed that her name wouldn’t be called. It was. The administrator wouldn’t answer any of her questions on the one-minute walk to the principal’s office or even look her in the eye. When she saw her mom and dad inside the office crying, she melted to the floor. “No, no, no, no!” she screamed.

The next student pulled from class was Justin Jurmu. His dad was sitting stone-faced in the assistant principal’s office, waiting for him, they both recall. “Jordan’s gone, buddy,” Justin’s father said softly. “He shot himself last night.”

Jordan had been Justin’s best friend since they were 8. “There’s no way, Dad,” he said. “There is zero chance Jordan is gone.” For 10 minutes, he shook his head, growing increasingly agitated.

Then he saw Kyla leaving the school, propped up by her parents. He watched her collapse, shoulders heaving. Her dad scooped her up and folded her into the back seat of his car. Justin howled.

Everyone in the school knew Jordan. He was the guy everybody was jealous of, the one who picked up a hockey stick and just knew how to play. He danced in the hallways between classes, headphones plugged in, blasting rap music. He had a big ego and wasn’t afraid to admit it. “Jeez, how can one young man be so happy all the time?” his football coach, Eric Mason, asked Jordan a week earlier. “That’s just the way I am, Coach,” Jordan chimed back.

Marquette is a city of 20,000 where front doors are rarely locked and stolen mountain bikes make the news. Nothing stays secret for long. The school administrator who escorted Kyla to the principal’s office is also her next-door neighbor. Kyla’s dad attended high school with Detective Larson’s sister and now works at the local bank where John DeMay is a client.

Kyla’s parents had been high school sweethearts. They had married and had children young. Kyla and Jordan talked about doing the same. Jordan started attending church with her family and scrapped plans to seek a basketball scholarship at an out-of-state school. He applied to Northern Michigan University in Marquette, where Kyla was planning to go.

For their one-year anniversary, he asked his mom for Kohl’s cash to buy Kyla a promise ring. On her 18th birthday card, he wrote: “I want to spend the rest of my life with you. You would be such an amazing wife, mother, grandma, everything, and I cannot wait for those days to come.” He wore hair ties around his wrist in case she needed to pull her wavy blond hair into a ponytail. He was wearing one when he died.

Kyla’s phone wouldn’t stop vibrating. People were messaging her, asking if it was true that Jordan was dead. Rumors were spreading that Kyla had dumped him and that’s why he killed himself. She decided to get out of the house. That afternoon, she and a friend drove to Presque Isle Park, where Kyla and Jordan would go to watch the sun set. They parked at the end of the road, facing the lake, and tried to reckon with what had happened.

As Kyla fixated on the last text Jordan had sent her, new Instagram messages kept popping up. Strangers were finding her account because Jordan’s public Instagram profile looked like a tribute to her. Half of his photos were of the two of them together, kissing, cuddling, dancing at prom.

One message was from someone named Dani Robertts. The message contained no words, just a photo of Jordan exposing himself in his bathroom mirror.

Kyla stopped breathing. This was the first nude photo of Jordan she’d ever seen. He was wearing the red, white and pink plaid pajama bottoms that matched her own and the T-shirt he’d had on when he left her house. She looked at the time stamp: 3:30 a.m.

This must be the mistake he was talking about. “I need you to drop me home now,” she told her friend. Then she replied to Dani Robertts.

Kyla:What is this about?

Dani:Do you know him?

Kyla:Do you?

Dani:Answer me

Kyla:Who are you?

Dani:I bet you know him.

Kyla:That’s my boyfriend why

Dani:I swear I will ruin his life with this

Kyla:He killed himself last night. Please don’t

Dani:Do you want me to ruin his life?

Kyla:He’s gone. No

Dani:Do you want me to ruin his life? Yes or no

Kyla:He’s already ruined. Wdym

Dani:He his [sic] going to be in jail

Kyla:HES DEAD

Dani:And this will go viral

Kyla:HE SHOT HIMSELF

Dani:Haha.

Do you want me to end this. And delete the pics?

Yes or no....

Cooperate with me and this will end...

Just do as I say and all this will end.

Dani started video-calling Kyla on repeat. Kyla ran to her parents. “Something happened last night,” she sobbed. “Someone has a nude picture of Jordan.”

By the time word of the nude selfie got to Larson, it was late that Friday night. He immediately called Kyla. She told him about her message exchange with Dani Robertts, and Larson asked her for screenshots so he could investigate. He hung up at 10 p.m., ending a 15-hour shift, but at least now he was one step closer to the “why.”

First thing Saturday, he drove to the sheriff’s office. It was his day off, but he had to file a preservation request with Meta for all records associated with the Jordan DeMay and Dani Robertts accounts.

Meta has a portal for police to file requests to preserve records of accounts connected to criminal investigations. Like other social media companies, it has to hold the records—including emails, IP addresses, message transcripts and general usage history—for 90 days. It only hands over user data if it’s ordered to do so by a court.

There’s one way to expedite the request: file it as an emergency, meaning a child could be harmed or there’s risk of death. Larson believed this case qualified. He told Meta that a 17-year-old was already dead, and there was a high probability other kids were in danger, too.

Meta declined his request within an hour, he says. “The request you submitted does not rise to the level of an emergency,” the company responded.

“Screw you,” Larson thought. He drafted an affidavit and looked up the county magistrate who was on call that weekend. He asked her to sign a search warrant and a nondisclosure order so Larson could gain access to Dani Robertts’ records without alerting whoever was using the account that an investigation was underway. Larson got the signed documents back later that day and forwarded them to Meta. Then he waited.

“I was helpless,” Larson says. “I was at their mercy.” (A Meta spokesperson declined to answer Bloomberg Businessweek’s questions about the matter.)

The following night, as Larson was getting into bed, he received a notification that the judge-ordered report from Meta was ready. The five-hour message exchange between Dani Robertts and Jordan DeMay was worse than he could have imagined. He read it twice, adrenaline pumping at the brazenness of the blackmailer.

“I will watch you die a miserable death.”

Larson had found his why. His next question was who. It was clear to him that the messages had not been written by a teenage girl.

The Dani Robertts Instagram account records contained a clue: time-stamped IP addresses—a unique set of numbers that identifies a specific device on the internet. Larson plugged them into a geolocation tool, and it kicked back latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates. Whoever was running the Dani Robertts account was based in Lagos, Nigeria.

Larson called a friend, an agent in the FBI’s Marquette field office. “You got a minute?” Larson said. “I might need some help.”

That day, Jordan’s red iPhone XR was dropped off at the Michigan State Police Computer Crimes Unit in Marquette. Ryan Frazier, a digital forensics analyst who’d been on the force 10 months, opened the sealed evidence bag. He’d already heard about Jordan’s death and recognized his name. He’d played for the same high school football team a few years earlier.

Frazier needed a four-digit passcode to unlock the device. He tried Jordan’s birthday and those of his four younger sisters and his girlfriend. Then he called Jordan’s basketball and football coaches to ask about his jersey numbers. He wore 05 on the court and 02 on the field. Bingo. The device unlocked.

Frazier was able to extract a full file system from the phone until the moment of Jordan’s death. It was a digital footprint of Jordan’s usage history, including what applications were active, what time they were opened, what messages he sent and when. Frazier returned the iPhone to the sheriff’s office the next day along with his report.

Larson noticed there was no message history with Dani Robertts. Jordan had deleted the conversation before he killed himself. The last activity on the phone was his 3:30 a.m. message to Kyla and one he sent to his mom: “Mother, I love you.”

Recounting the specifics, Larson’s bottom lip starts to quiver. An imposing figure with a buzz cut, he asks to pause the interview, gets up from his desk, adjusts his holster and walks to the back of his office, looking for a tissue. “This case,” he mumbles under his breath, “it’s haunting.”

By mid-2022 sextortion was dominating NCMEC’s cybertip report line. In June the center summoned social media companies to an urgent meeting to warn them about the scam. More than 50 people joined the call, including representatives from Meta, Snap and TikTok.

NCMEC’s Coffren says she described the targets, the motives and the mechanics of the crime, warning that some teenage boys had already killed themselves. “We need you to take action. Fast.”

The month after the call, the 17-year-old son of Brandon Guffey, a Republican South Carolina state representative, received an Instagram message late on a Tuesday night. “Your cute,” it said. The message was from a biracial girl wearing a crop top in her profile photo. Her bio said she was a freshman at a nearby college.

Gavin Guffey was in his bedroom playing video games with friends online. He told them he was going to drop off to chat with a girl. It didn’t take long for the conversation to turn risqué. She sent a sexy photo and asked for one in return. When he complied, she threatened to forward it to everyone he was friends with on Instagram unless he sent her money. He paid $25 via Venmo. It wasn’t enough. Around 1 a.m. she sent a mock-up of a news story with his photo and the headline “Gavin Guffey Caught Sending Nudes on the Internet.”

According to his father, who’s seen a transcript of the conversation, Gavin wrote back that he was going to end his life if the photos came out. Less than an hour later, he did.

His father, who had just returned from a political event, heard a shot from inside the bathroom and kicked down the door. His son was already gone.

A few days later, while planning Gavin’s funeral, Guffey got a call from an aunt who shares the same last name. She said her 14-year-old son had been contacted online by someone claiming to be Gavin’s girlfriend, saying dangerous people were blackmailing her over nude photos of Gavin. She said they were going to ruin her life if she didn’t pay them $2,000.

When Guffey opened his own Instagram account, he found a similar message. “She said she needed to talk to me right away and that she was going to ruin my political career,” Guffey says.

A month later, in August 2022, Guffey was in Myrtle Beach with his wife to mark what would have been Gavin’s 18th birthday. He was sitting on the back deck of a family member’s condo with a glass of bourbon, smoking a cigarette, when a WhatsApp message from a random number flashed on his screen. It said: “Did you know your son begged for his life 😂”.

Guffey snapped. “I will f---ing end you,” he replied. A back-and-forth between Guffey and the scammer ensued, lasting for hours. They sent him photos of his house from Google Street View, threatening to break in. He invited them to do so: “I will kill you with my bare hands.” In the end, the scammer told Guffey he was sorry about what had happened to his son and said he’d been hired by a political opponent. No arrests have been made, but Guffey says an FBI investigation is ongoing. The FBI didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Since sharing the story of his son’s death, Guffey says he no longer silences his phone at night. That isn’t for the blackmailers; it’s for their victims. He says he’s received about 200 calls from teens, usually between midnight and 3 a.m.: “I’ll answer, and they’ll say, ‘Mr. Guffey, what happened to Gavin is happening to me. Please help!’ ”

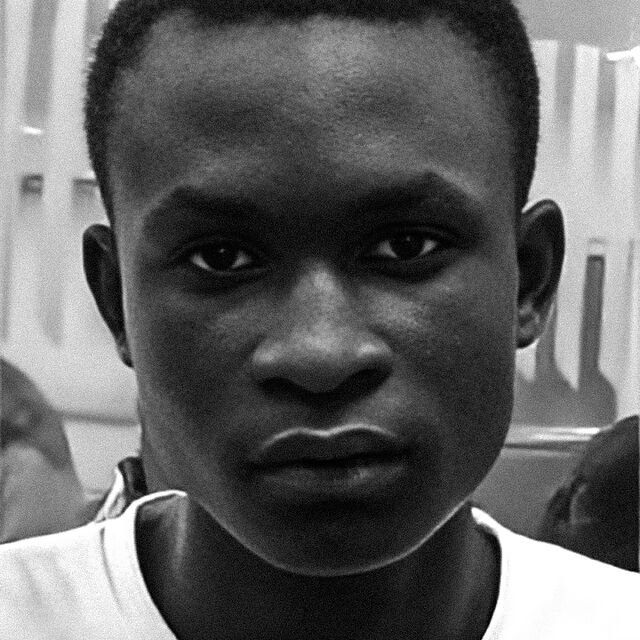

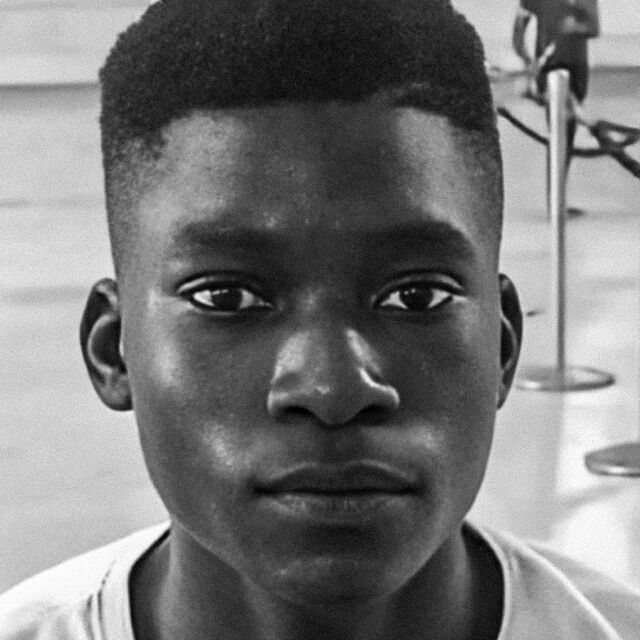

By early 2023, FBI agents in Michigan were homing in on an apartment complex in Lagos. Social media records and email addresses obtained from Apple, Google and Meta linked two brothers who lived there to the crime. Buried inside their Gmail and iCloud accounts, FBI agents found evidence that Samuel and Samson Ogoshi, 22 and 20, respectively, had bought hacked Instagram accounts, including the one being used by the fictitious Dani Robertts. They had 12 photos including the profile picture of the account’s original owner, a teenage girl who hasn’t been identified, as well as the nude photo of Jordan DeMay and the Photoshopped collage sent to torment him. Their emails contained a word-for-word script of what was in the messages sent to Jordan the night he died.

The FBI found evidence that the brothers had used the Dani Robertts account to message Jordan and target more than 100 other victims in the US, according to court records. On the same day Jordan died, they were messaging another victim in Warrens, Wisconsin, threatening to “make u commit suicide.”

The agents also found an incriminating Google search history that included “Instagram blackmail death,” “Michigan suicide,” “how to hide my IP address without VPN?” and “how can FBI track my IP from another country.”

The Ogoshi brothers were arrested by Nigerian authorities in January 2023. Court records show they come from a middle-class family. Their father is a retired member of the military, and their mother runs a small business selling soft drinks in their apartment complex. The boys grew up attending church, singing in the choir and playing soccer with neighborhood friends. The older brother, Samuel, was studying sociology at Nasarawa State University, while Samson was training to be a cobbler.

In August the brothers left Nigeria for the first time, escorted by the FBI. They were extradited to Grand Rapids, Michigan, to face federal charges in connection with the death of Jordan DeMay. A third defendant, Ezekiel Robert, has been arrested and is appealing a Nigerian extradition order.

The FBI says the Ogoshi brothers and Robert worked with three unnamed co-conspirators, according to court documents. They bought the hacked Instagram account from one and got the victims to pay a US-based money mule, someone who converted the payment into cryptocurrency before sending it to another co-conspirator in Nigeria. The Ogoshi brothers told the FBI they received only a portion of the money they extorted.

During the brothers’ extradition proceedings, the US government promised it wouldn’t seek the death penalty. On April 10 they pleaded guilty to conspiring to sexually exploit teenage boys and face mandatory sentences of 15 years in prison. The maximum possible penalty is 30 years. Their attorneys didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In the meantime, they are being held in a county jail in White Cloud, Michigan, about an hour north of Grand Rapids and 6,000 miles from Lagos. They haven’t been allowed to speak to each other. For entertainment, they have playing cards, books and a communal TV. They get one hour of recreation a day in a small outdoor courtyard.

One morning in February, as icicles hung from the barbed wire, Samson Ogoshi opted to stay inside. Wearing open-toe sandals and white socks, his orange jumpsuit pants rolled up above his ankles, he did squats with other inmates in a communal day room as a Businessweek reporter watched on a security camera. With snow piling up knee-deep in the courtyard, Ogoshi must have felt out of place, says the county sheriff, who’s in charge of the jail; he’d probably never seen snow before.

In November another Nigerian, Olamide Oladosu Shanu, was indicted for running a similar sextortion ring that received more than $2.5 million in Bitcoin from victims. The US Secret Service spent months investigating Shanu, who allegedly worked with four co-conspirators to hack social media accounts of teenage girls in the US and persuade teenage boys to send nude photos and videos of themselves, according to a 21-page indictment filed in federal court in Idaho.

The Ogoshi and Shanu alleged crime rings are the modus operandi of Nigeria’s Yahoo Boys, according to a January report written by Paul Raffile, an analyst at the Network Contagion Research Institute in Princeton, New Jersey. Nicknamed after the Yahoo.com emails they used to swindle thousands of unsuspecting Westerners into sending money, often posing as Nigerian princes, the Yahoo Boys are a group of digitally savvy con men who design new scams and encourage others to copy them.

Raffile found hundreds of instructional videos on TikTok and YouTube about how to blackmail teens. They were posted by young men in Nigeria who used the hashtags #YahooBoysFormat and #BlackmailFormat. The how-to guides advised targeting, or “bombing,” American high schools and sports teams to make friends with as many kids as possible from the same community. One of Jordan’s football teammates was a mutual friend of Dani Robertts’, which made her account appear legitimate.

Raffile says he started studying sextortion last year after a friend was blackmailed and asked for help. He read victims’ stories in news reports, Reddit forums and social media posts and was struck by the similarities of their experiences, especially when it came to the blackmail script. “There was some mystery to this,” Raffile says, “like invisible organized crime.”

The Yahoo Boys videos provided guidance on how to sound like an American girl (“I’m from Massachusetts. I just saw you on my friend’s suggestion and decided to follow you. I love reading, chilling with my friends and tennis”). They offered suggestions for how to keep the conversation flowing, how to turn it flirtatious and how to coerce the victim into sending a nude photo (“Pic exchange but with conditions”). Those conditions often included instructions that boys hold their genitals while “making a cute face” or take a photo in a mirror, face included.

Once that first nude image is sent, the script says, the game begins. “NOW BLACKMAIL 😀!!” it tells the scammer, advising they start with “hey, I have ur nudes and everything needed to ruin your life” or “hey this is the end of your life I am sending nudes to the world now.” Some of the blackmail scripts Raffile found had been viewed more than half a million times. One, called “Blackmailing format,” was uploaded to YouTube in September 2022 and got thousands of views. It included the same script that was sent to Jordan DeMay—down to the typos.

While YouTube and TikTok are the preferred platforms for how-to videos, the extortion typically happens on Instagram or Snapchat, according to Raffile’s report. Instagram contains extensive personal information blackmailers can use to torment victims, including their location, school and friends. Snap’s disappearing messages give users a false sense of security that their images aren’t being saved. Both companies say they have zero tolerance for this crime and have vowed to do more to protect their users.

Snap has been “ramping up our tools to combat” sextortion, a company spokesperson says. “We have extra safeguards for teens to protect against unwanted contact and don’t offer public friend lists, which we know can be used to extort people.”

Antigone Davis, Meta’s global head of safety, said in an emailed statement that sextortion “is a horrific crime, and we’ve spent years building technology to combat it and to support law enforcement in investigating and prosecuting the criminals behind it.” She said scammers keep changing their tactics, but the company tracks new trends “so we can regularly improve our tools and systems.”

Meta says it’s using artificial intelligence to detect suspicious activity on the platform and to blur nudity and is now showing teens a sextortion-focused safety notice if they message with a suspicious account. And it has helped run a training session in Abuja, Nigeria, to educate law enforcement and prosecutors there. Meta is also a founding member of Take It Down, an initiative launched by NCMEC last year for teens to flag intimate images and block them from being shared across social media.

Raffile says none of the companies contacted him after his report was published and before Businessweek made inquiries. Social media companies “could have curbed this crime from the beginning,” he says. “It’s a disastrous intelligence failure that over the past 18 months all these deaths and all this trauma was preventable with sufficient moderation.”

In January, Jordan’s parents filed a wrongful death lawsuit in a California state court accusing Meta of enabling and facilitating the crime. That month, John DeMay flew to Washington to attend the congressional hearing with social media executives. He sat in the gallery holding a picture of Jordan smiling in his red football jersey.

The DeMay case has been combined with more than 100 others in a group lawsuit in Los Angeles that alleges social media companies have harmed children by designing addictive products. The cases involve content sent to vulnerable teens about eating disorders, suicide and dangerous challenges leading to accidental deaths, as well as sextortion.

“The way these products are designed is what gives rise to these opportunistic murderers,” says Matthew Bergman, founder of the Seattle-based Social Media Victims Law Center, who’s representing Jordan’s parents. “They are able to exploit adolescent psychology, and they leverage Meta’s technology to do so.”

Bergman also represents a family from Arizona whose 14-year-old son was blackmailed after sending nudes. And Guffey, the South Carolina lawmaker, filed his own wrongful death case against Meta. A spokeswoman for Meta says the company can’t respond to questions about these cases because litigation is pending.

The lawsuits face a significant hurdle: overcoming Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. This liability shield has long protected social media platforms from being held accountable for content posted on their sites by third parties. If Bergman’s product liability argument fails, Instagram won’t be held responsible for what the Ogoshi brothers said to Jordan DeMay.

Regardless of the legal outcome, Jordan’s parents want Meta to face the court of public opinion. “This isn’t my story, it’s his,” John DeMay says. “But unfortunately, we are the chosen ones to tell it. And I am going to keep telling it. When Mark Zuckerberg lays on his pillow at night, I guarantee he knows Jordan DeMay’s name. And if he doesn’t yet, he’s gonna.”