The extraordinary life of Los Bravos singer Mike Kennedy, a genuine musical rebel

Of German descent, he was Spain’s first rock star. He was an international hit but lost everything due to extravagant behavior. ‘I’ve been my own worst enemy,’ he tells EL PAÍS from a care home in the city of Vitoria, as he’s about to turn 80 years old

Mike Kennedy knows that he will no longer sing in public. But still, there’s some melody left in his voice, as he tells EL PAÍS the extraordinary story of his life from his room in a long-term care home in Vitoria, in northern Spain. He especially enjoys singing a tune – Louisiana (1970) – from his solo career.

Michael Volker Kogel (his real name) was Spain’s first rock star in the canonical sense. As a teenager, he rose to fame as the lead singer of Los Bravos. He became known for his wild attitude, his carefree way of living, his persistent rebelliousness and his inevitable decadence.

“He was a force of nature. He sang as well as Gene Pitney or Del Shannon, in the same register, but with more volume in his voice. [Nobody had ever heard] such a peculiar voice,” asserts Miguel Ríos, one of the pioneers of rock and roll in Spain, who was consulted for this story.

In the 1960s, Kennedy — who was born in Germany — landed in Spain. He brought with him his outlandish character, his hypochondria and an anarchist attitude to a frightened, conservative country living under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. “I’ve always been my own worst enemy. I trust that you’ll be tough on me,” Kennedy jokes with the interviewer.

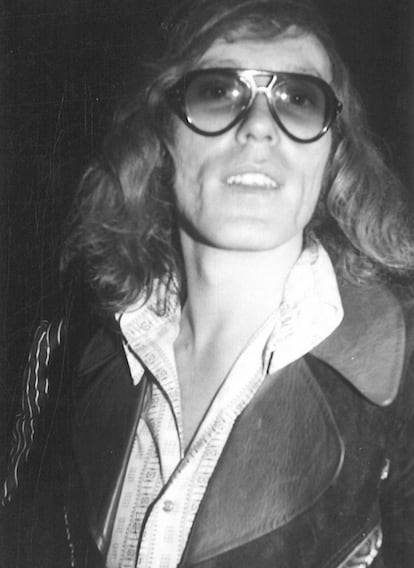

In many images from his golden era, Mike Kennedy poses while wearing tinted sunglasses. But during his conversation with EL PAÍS, his sky blue eyes are visible. They fill with tears at some points, as he remembers moments from his life.

During the interview he is accompanied by Begoña Arteaga, his guardian angel for the last 15 years, a woman who has tried to bring order to the chaotic life of an ungovernable man. “If it wasn’t for Begoña, I’d be dead,” the singer acknowledges. On April 25, he will turn 80 years old. And, at the moment, he cannot foresee a life in which he isn’t provided with round-the-clock care.

Kennedy didn’t have a very good relationship with his parents. His mother was an actress with an expansive character [who left her husband]. His father, who worked in an actor’s cabaret, barely spent time with his family. “My mother was very nice and she wanted to live her own life. She had the man she wanted. In the emotional sense, or from the standpoint of being looked after, you could say that I didn’t have parents,” Kennedy reflects, with an air of sadness. His mother committed suicide when she was 65.

“I was raised by my grandmother… she was everything to me. She was a Jehovah’s Witness and she indoctrinated me. But eventually, I lost the fervor.” This religiosity lasted for a few years. In the mid-1960s, the first time his band, Los Bravos, decided to make a trip to the United States, Kenney refused to fly. The American authorities were demanding that visitors be vaccinated and, because of his faith, “he wasn’t allowed to.” Eventually, though, he was convinced.

He was born in a dreary Berlin in the 1940s. When he finished school, he moved to Cologne to live with his mother and stepfather. There, he worked serving beer in pubs and performing nightly in the clubs. “I learned to sing because I was a big fan of Elvis Presley. I imitated his voice, his gestures, his makeup. Pat Boone, Eddie Cochran and Ricky Nelson also fascinated me,” he explains. He learned English by listening to the American Forces Network (AFN), the broadcaster for U.S. troops stationed in Germany.

His life was transformed when, while performing at a club in Cologne, he ran into some Spanish musicians from Mallorca, who were touring in Germany. They were called the Runaways. And when the group’s singer returned to Spain because his vocal chords were destroyed after working eight-hour-long days, Kennedy was left to occupy the position of vocalist. And that’s how Mike and the Runaways were born. After their German experience, the band returned to Mallorca, and he went with them. “It was a liberation to come to Spain. My intention wasn’t to succeed. I just wanted to lie on the beach and enjoy the sun,” he smiles.

While he was in Spain, Los Sonor, an established ensemble, signed Mike and some of the Runaways. And this is when composer Manolo Díaz comes into play. He had years of experience as the president of CBS Records in Spain and EMI Music in Latin America.

“Los Sonor told me that they had gone to see this new singer, who was very good… but he was completely crazy and was a kleptomaniac and an anarchist. [He was] very punk… and we’re talking about the 1960s in Spain. But when he started singing, it was impressive. I recommended that [the members of] Los Sonor bear with him and support him, because his voice and his way of singing were among the best in global pop-rock. I told them: ‘You can’t miss out on this, you’re going to make millions.’”

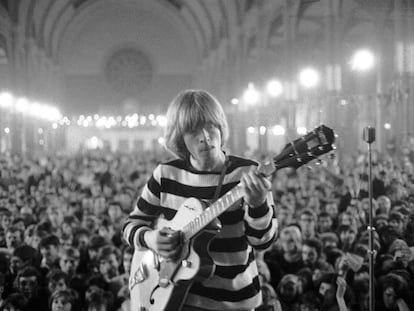

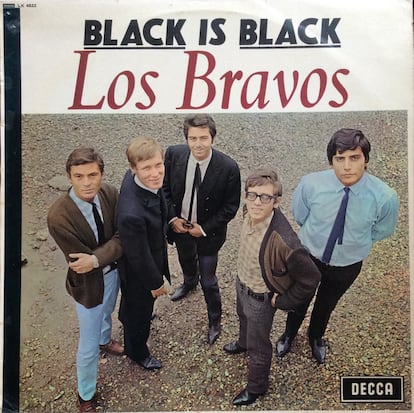

Díaz contacted Alain Milhaud, a Frenchman based in Barcelona who was responsible for getting 1960s Spanish pop to the global market. And then, there was Tomás Martín Blanco, a radio giant in Spain. The plan got quickly underway: with Díaz composing, Milhaud acting as producer and manager (with contacts in the United Kingdom and United States) and Martín Blanco pushing the songs on the airwaves, a new band was born. “[Los Bravos] became the most successful and international Spanish band of all time,” says Salvador Domínguez, who has written extensively about the history of pop-rock in Spain.

The album Black is Black was composed by a group of writers from Decca Records, based in London. It was established in the British capital with a strict rule laid out by the Musicians’ Union: all instruments that were purchased in the United Kingdom had to be played by English professionals. So, Los Bravos packed up all their gear and headed off to London… but Mike, the singer, preferred to record alone.

It’s rumored that Black is Black touched Jimmy Page (the founder of Led Zeppelin), although this has never been confirmed. But John Bonham, Led Zeppelin’s impulsive drummer, participated in the recording of Bring a Little Lovin, another international success for Los Bravos.

“I didn’t like Black is Black… I followed along without liking it. It seemed to me like an easy melody, [with lyrics] that didn’t say much,” Kennedy shrugs, clinging to his self-destructive nature. The song went to number one on the charts in Spain and Canada, number two in the UK and number four in the United States, all between 1966 and 1967.

At the time, Manolo García was 13 years old and getting ready to form El Último de la Fila, a leading Spanish rock band that he still fronts today. “The fact that Black is Black made it onto the English and American lists was a source of pride for Spanish teenagers at the time. It was like: ‘[wow], a Spanish band triumphing in the United States. What’s happening?’” he explains over the phone.

“Los Bravos [and other bands like them, including] Los Brincos, Los Mustang… they conquered a country that was yearning for music. Those were times of dictatorship, very gray, the [cultural output] was garbage. They were a breath of fresh air… the young people [of the 1960s] wanted to breathe. It was a breath of modernity. And it was also convenient for the dictatorship to open things up, even if the intentions were bad.”

Kennedy gave the group a cosmopolitan air: he sang in fluent English and, despite lacking in Spanish, displayed a charismatic, uninhibited character. His songs in Spanish are tinged with the peculiar accent of an outsider. On top of that, at the time, the songs offered subtle messages that managed to get past the formal censorship. In the background, Manolo Díaz composed odes to youth, to fun and to freedom.

The success of Los Bravos was ephemeral, lasting only two years, from 1966 until 1968, but intense. They filmed two music videos to wide acclaim — Los chicos con las chicas (“Boys with girls,” 1967) and ¡Dame un poco de amooor...! (“Give me a little love,” 1968) — and indulged in the eccentricities of stars. They arrived at shows in horse-drawn carriages and landed in helicopters to perform in bullfighting plazas. Once, Kennedy even burst onto the stage while riding a motorcycle.

Every song that they put out that took advantage of Kennedy’s aggressive and powerful voice — Black is Black, Los chicos con las chicas, Bring a Little Lovin’ – had a huge impact, both in English and Spanish. However, while the bandmates made a lot of money in a short period of time, they never held the rights to their work. Without a doubt, this resulted in financial troubles in the long term.

Manolo García notes that “there was a lot of innocence and ingenuity in Spain… young people [were attracted to] everything that involved playing, partying, rocking, drinking, smoking... and that’s what Los Bravos [were all about]. They opened up the hedonistic spaces of life that the military regime had repressed.”

Kennedy assumes that, to a great extent, his own difficult nature caused the band to break up. The singer was spending a lot of time with a doctor, who was basically stuck to him. He explains: “I was a [total] hypochondriac. Everything started before a concert in Istanbul, in 1967. I wanted to try [some hashish] and it was mixed with alcohol and amphetamines. We took amphetamines like candy to hang in there, because we played for eight hours straight. Then, with that cocktail, I went to perform and felt terrible. I had arrhythmias, it felt like my heart was stopping, I had to hold myself up against a wall…”

" [That incident] became an obsession,” he notes. “I still [get that feeling] sometimes; it’s like having ants all over my body. So I always brought the doctor with me, to be able to calm down. But I never had any problems with strong drugs. Hashish, amphetamines… I’ve seen people do LSD, but I never took it, I was too scared.”

Miguel Ríos offers some insight: “When he left Los Bravos, he spent a few years as a soloist. I was amazed that he could get drunk and then go up on stage and sing like it was nothing, perfectly in tune. It’s possible that Mike was shy and needed to drink to combat stage fright. To sing so well, he’s spent a lot of time hungover.”

Another incident marked the end of Los Bravos. In April 1968, Manolo Fernández, the keyboardist, had a car accident in which his wife was killed. A month later, Fernández, heartbroken, wrote a farewell note and shot himself in front of an altar in his house, which was covered with photos of his deceased wife. At the time, suicide was a taboo subject.

This tragedy – along with the troubles that Kennedy was having with the rest of the group – put an end to the original band.

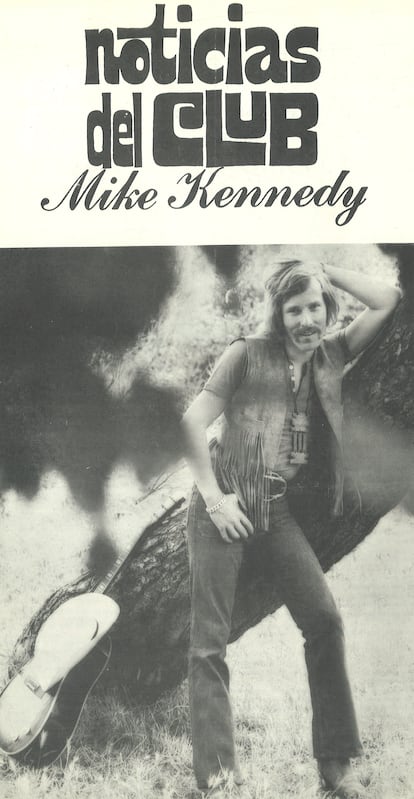

Kennedy published 70 good songs over the course of his solo career, but he never reached the level of success that he had when he was with the band. He also refused to follow the rules, something that also didn’t help.

“I refused to sing some songs that Milhaud gave me. I should have listened to him, but I always had a difficult character. I do harm to myself. Even today. I’ve had a lot of regrets, but I’m still the same mess as always. I should have been more demanding of myself, but I was a major narcissist,” he admits.

Manolo Díaz adds: “Mike didn’t have the business sense or discipline to move his career along. Milhaud and I took advantage of his enormous ability as a singer, but we weren’t able to help him establish himself. He continued to be an anarchist.”

As a record label director, Díaz has worked with dozens of performers, from Julio Iglesias to Enrique Bunbury. “Of all the artists I’ve met, Mike was the most detached from the music business… it didn’t matter to him. He enjoyed success, but he didn’t do anything to get it.

On the contrary: everything he did made [being successful] more difficult. But his voice and his way of singing… there was never anyone in Spain who could compete with him in [the genre of] pop-rock. Not even today.”

Bertha Yebra, the editor of Rock and Roll Popular 1 Magazine, has known Kennedy for 50 years. In a phone call with EL PAÍS, she emphasizes that, “together with Nino Bravo, he’s been the best voice in Spanish music. During his moment of popularity, when he was making lots of money, he would give you whatever you asked for. He would walk into a restaurant and pick up the tab for everyone. He was a crazy and extravagant star.”

The 1980s brought about the golden age of Spanish pop, erasing the musicians from the 1960s. Kennedy, however, continued seeking adventure. He spent time in Latin America — “I was almost kidnapped by the guerrillas in El Salvador” — and participated in some reunion performances organized by Los Bravos. He lived in Barcelona, Mallorca, Valencia, Madrid; he joined the nostalgia tours with other musicians from the 1960s.

“I ended up making a lot of money, but it went like wine,” he confesses. For the last 15 years, before moving to a long-term care home, Kennedy lived in Vitoria, all alone, on the fourth floor of a walk-up building. His apartment was 450-square-feet. “I was happy there.” He used to ride around on a bike and perform in small clubs for a handful of euros. His life was managed by Begoña Arteaga, 70, who has been his caregiver for many years now.

“I always liked Mike Kennedy. I was part of Mike’s fan club when I was a young girl. My husband and I used to follow his career, we sort of got in touch. And, 15 years ago, I suggested that Mike come to Vitoria,” she recalls.

Since then, Begoña has practically been the singer’s only support system. She cooks for him and handles his affairs, looking for gigs here and there. She also manages his social agenda, as Kennedy doesn’t have any children. His only family member is his mother’s brother, who lives in Germany. The two men don’t meet up, but they speak occasionally by phone.

This past October, Kennedy suffered a fall in his apartment and Begoña found him lying on the floor. He had been there for at least 24 hours. After that, he was in the hospital for a long time, until he ended up in the long-term care home where he now resides. He’s improving little by little, but he needs help to walk. His last concert was in 2016, in Madrid, where he shared the stage with other members of iconic bands from the 1960s.

Kennedy doesn’t have any major material assets: no house, no car. His financial situation isn’t the best. He doesn’t get any songwriting royalties from Los Bravos’ greatest hits. But he’s managed to stay afloat with some singing royalties. For instance, Quentin Tarantino included Bring A Little Lovin’ in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019), and this brought Kennedy, in his words, “a bit of money.”

Manolo García is carrying out efforts so that the Spanish Society of Authors and Publishers, which handles artists’ copyrights in Spain, will address this situation. “To me, it seems like a disgrace to leave people [destitute].

Any musician who has formed part of bands that have brought joy and life to the country should get a pension… lots of European countries, including France, do this with public money, given all the taxes we pay. He’s not going to buy a yacht for God’s sake, he just needs a dignified [retirement]. Mike Kennedy deserves a pension of at least €1,500 [a month],” García insists.

In recent years, before she died, Kennedy had been exchanging voice notes with the famous Spanish actress Concha Velasco. “She was a great friend. She cheered me up when I was ill. And she told me that, someday, we would get married,” he smiles.

He tries to sing a song, but he can’t. “Dammit, what’s wrong with my voice… well, I guess I’m in bed all day, I just talk to myself. And when I want to sing, it doesn’t come out.”

Despite so much sadness in recent times, Mike Kennedy has managed to find a little joy. He was able to see Los Bravos in a New Year’s special on TV. He actually visited the same television program many times in the 1960s, but he never watched it. “Shame I had to see it from bed. That’s the way it is…”

After the interview, upon leaving the residence, his doctor informs EL PAÍS, with a dash of humor, that, a few days before the singer arrived in the facility, he wrote in his file: “Watch out: he’s a warrior.” Indeed, that’s what Mike Kennedy has been all his life.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition