Shift Your Mindset is a monthly series from CNN’s Mindfulness, But Better team. We talk to experts about how to do things differently to live a better life.

Since time immemorial, humans have done their darnedest to try and cheat death. Today, as revolutionary advancements transform the stuff of science fiction into everyday reality, are we closer to extending our lifespan or even perhaps immortality?

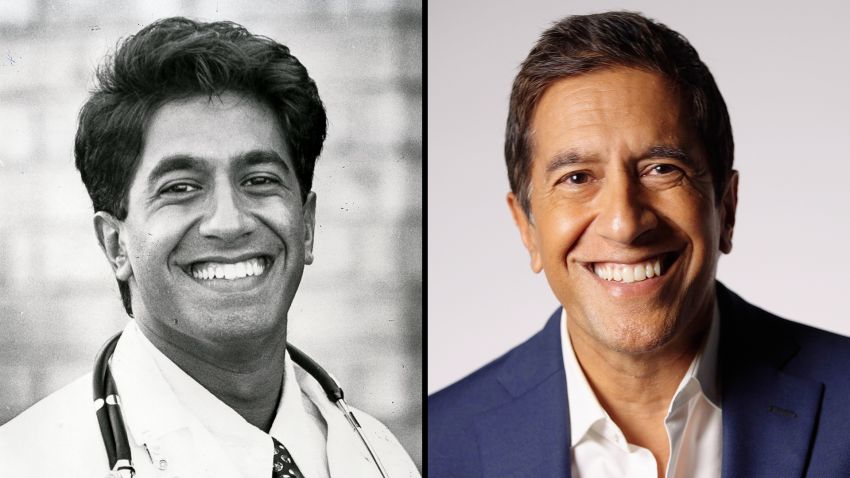

If so, do we really want eternal life? In his new book, “Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for Immortality,” Nobel Prize-winning molecular biologist Venki Ramakrishnan sifts through past and cutting-edge research to uncover the aspirational theories and practical limitations of longevity. Along the way, he raises critical questions about the societal, political and ethical costs of attempts to live forever.

Already, humans live twice as long as we did 150 years ago due to increased knowledge about diseases and their spread. Does that suggest interventions to triple or quadruple our lifespan lie just around the corner? Ramakrishnan shares his perspectives on the realities of aging, death and immortality.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

CNN: What is aging? How does it lead to death?

Venki Ramakrishnan: Aging is an accumulation of chemical damage to the molecules inside our cells, which damages the cells themselves, and therefore the tissue, and then eventually us as an organism. Surprisingly, we start aging when we’re in the womb, although at that point, we’re growing faster than we’re accumulating damage. Aging happens throughout our lives, right from the very beginning.

The body has evolved lots of mechanisms to correct age-related damage to our DNA and to any poor-quality proteins we produce. Without ways to correct these sorts of problems, we would never live as long as we do. Still, over time, damage begins to outpace our ability to repair.

Think of the body as like a city containing lots of systems that must work together. Once an organ system critical to our survival fails, we die. For example, if our muscles become so frail that our heart stops beating, it can’t pump the blood containing the oxygen and nutrients our organs need and we die. When we say someone dies, we mean the death of them as an individual. In fact, when we die, most of ourselves, such as our organs, are alive. This is why the organs of accident victims can be donated to transplant recipients.

CNN: Does human lifespan have a fixed limit?

Ramakrishnan: The lifespans of all organisms range from a few hours or days for insects to hundreds of years for certain whales, sharks and giant tortoises. A layperson might assume that all life forms are preset to die once they’ve reached a certain age. But biologists don’t believe that aging and death are programmed in the sense that a fertilized egg is programmed to develop into a human being.

Instead, evolution has optimized a lifespan equation of resource allocation that’s optimized for every species. Larger animals tend to live longer. If you’re a small animal — and therefore more likely to get eaten by a predator, starve or die in a flood — it makes no sense for evolution to waste resources repairing the damage necessary to keep you alive longer. Instead, evolution selects for growing fast and maturing quickly so you can reproduce and pass along your genes.

If you’re a larger animal, staying alive longer will grant you a better chance of finding a mate with whom you can have more offspring over your longer lifetime. Lifespan is all about evolution maximizing the chances of your passing along your genes. In humans, this finely tuned resource balance grants us a maximum lifespan of about 120 years. But that doesn’t mean we can’t alter biology and intervene in these processes of aging, and maybe extend our lives. Like many aging scientists, I believe that it’s possible. I don’t, however, share their optimism for how feasible such interventions would be.

CNN: Who has lived the longest so far?

Ramakrishnan: The oldest person for whom we have reliable records was a French woman named Jeanne Calment, who died in 1997 at age 122. She smoked for all but the last five years of her life and ate more than two pounds of chocolate every week. But I wouldn’t recommend those particular strategies for longevity, except for the chocolate perhaps.

CNN: Can the aging clock ever run backward?

Ramakrishnan: The aging clock does run backward, every generation. Although a child is born from the cells of adult parents, the child still starts at age zero. A child born to a woman who’s 40 years old is not 20 years older than a child born to a 20-year-old; they’re both starting at zero. So, at some level, the aging clock can reverse.

There’s also cloning. While Dolly, perhaps the most famous cloned sheep, was sickly and died at about half the normal age, other cloned sheep have gone on to live normal lives. This has convinced some that resetting the aging clock must be possible on a wider scale. While tricking adult cells into becoming embryonic and beginning to grow again has been successful, practical difficulties make cloning very inefficient. Many cells have accumulated too much damage to take, which necessitates an enormous number of experiments to grow a single animal.

Experiments in mice, meanwhile, have used cellular reprogramming so that cells can revert developmentally, partway, to have the capacity to regenerate tissue. By converting cells to a slightly earlier state, scientists have produced mice with better blood markers and improved fur, skin and muscle tone. Despite all the research in this area, I’m not sure how easy it’s going to be to translate into something useful for humans.

CNN: Your father just turned 98. What bearing will his good health and independence likely have on your own life? How much of aging and longevity are influenced by genetics?

Ramakrishnan: There is a correlation between the ages of parents and their children, but it’s not perfect. A study of 2,700 Danish twins showed that heritability — how much of our longevity is due to our genes — only accounted for about 25% of lifespan. Still, researchers have found that mutation in just a single gene can double the lifespan of a certain type of worm. Clearly there’s a genetic component, but the effects and implications are complex.

CNN: What does cancer science reveal about anti-aging research?

Ramakrishnan: The relationship between cancer and aging is complicated. The same genes can have different effects over time, helping us grow when we’re young but increasing risk of dementia and cancer when we’re older. Our risk of cancer increases with age because we accumulate defects in our DNA and genome, which sometimes cause gene malfunctions that lead to cancer. But many of our cellular repair systems that seem to be designed to avoid cancer early in life also cause aging later.

For example, cells can sense breaks in our DNA that might allow chromosomes to join in an abnormal way, which could lead to cancer. To prevent that joining, a cell will either kill itself or enter a state called senescence, where it can no longer divide. From the perspective of an organism like us, which has trillions of cells, this makes sense. Even if millions of cells are destroyed this way, these actions protect the whole organism. But the buildup of senescent cells is one of the ways we age.

CNN: Has your research on why we die influenced how you live your life?

Ramakrishnan: It’s interesting that all the evidence-based recommendations for what can help us live a long, healthy life reflect the common-sense advice that’s been passed on through the ages. We got it from our grandmothers: Don’t be gluttonous. Get exercise. Avoid stress, which creates hormonal effects that change our metabolism and can accelerate aging. Get enough sleep.

Aging research is helping us understand the deep biological implications of this advice. Eating a variety of healthy foods in moderation can prevent the health risks of obesity. Exercise helps us regenerate new mitochondria — the powerhouses of our cells that provide energy. Sleeping allows our bodies to do molecular-level repair. Learning the biology behind this age-old, rock-solid advice can encourage us to take other actions that will help promote a long and healthy life.

Personally, I often say I’m way past my expiration date, but as a human being, I still feel like I’m alive and have things to contribute.

CNN: What are the societal costs of the quest to cheat aging and death, particularly inequities?

Ramakrishnan: Already the top 10% of income earners in both the US and the UK live more than a decade longer than the bottom 10%. If you look at health span — the number of years of healthy life — that disparity is even greater. Poorer people are living shorter, less healthy lives.

Many very rich people are pouring huge amounts of money into research, hoping to develop sophisticated technologies to prevent aging. If these efforts succeed, the very rich will benefit initially, followed by people with very good insurance, and so on. Rich countries will likely have access before poorer countries. So, both within countries and globally, such advancements have the potential to increase inequalities.

CNN: Has exploring this topic changed your thoughts and feelings about aging and dying?

Ramakrishnan: Most of us don’t want to get old or leave this life. We don’t want to go while the party’s still going on. But even as cells in our body are made and die all the time, we continue to exist. Similarly, life on Earth will go on as individuals come and go. At some level, we have to accept that’s just part of the scheme of things.

I think this quest for immortality is a mirage. One hundred and fifty years ago, you could expect to live until about 40. Today, life expectancy is about 80, which, as author Steven Johnson has said, is almost like adding a whole extra life. But we’re still obsessed about dying. I think if we lived to be 150, we’d be fretting about why we’re not living to 200 or 300. It’s never-ending.

Jessica DuLong is a Brooklyn, New York-based journalist, book collaborator, writing coach and the author of “Saved at the Seawall: Stories From the September 11 Boat Lift” and “My River Chronicles: Rediscovering the Work That Built America.”