For another five hours and 47 minutes, I can buy a Royal Blue Twist Front Cloak Sleeve Slit Back Dress for $5.90, a Striped Pattern High Neck Drop Shoulder Split Hem Sweater for $8.50, or a Solid Sweetheart Neck Crop Tube Top for $1.90. When today’s 90%-off sale ends at 8pm, the crop top will revert to its original price: $4. There are 895 items on flash sale. On today’s “New In” page, there are 8,640 items (yesterday there were 8,760). The most expensive dress of the nearly 9,000 new arrivals – a floor-length, long-sleeved, fully sequinned plus-size gown, available in five sparkly colours – is $67. The cheapest – a short, tight piece of polyester with spaghetti straps, a cowl neckline and an all-over print of Renaissance-style flowers and cherubs – is $7.

I can buy casual dresses, going-out tops, workout leggings, winter parkas, pink terry-cloth hooded rompers, purple double-breasted suit jackets with matching trousers, red pleather straight-leg pants, cropped cardigans with mushroom embroidery, black sheer lace thongs and rhinestone-trimmed hijabs. I can buy a wedding dress for $37. I can buy clothes for school, work, basketball games, proms, funerals, nightclubs, sex clubs. I see patchwork-printed overalls and black bikinis with rhinestones in the shape of a skull over each nipple designated as “punk”. I can buy Christian-girl modesty clothing and borderline fetish wear.

In the grid of product listings, a yellow rectangle indicates if a product is trending: “Trending-Plazacore”, “Trending-Western”, “Trending-Mermaidcore”, and “Trending-Y2K” tags all appear in the new arrivals. “Plazacore” is blazers and faux-tweed in pastels and beige. “Mermaidcore” means a pile up of sequins and glitter. “Western” brings up fringe jackets and bustier tops, fake leather cowboy boots and leopard-print silk blouses. The collection is unimpressive in small doses but starts feeling remarkable as you click through the pages. If I search the word “trending”, there are 4,800 items labelled with trends I’ve never heard of even after a decade-plus of closely following fashion blogs and Instagram accounts: Bikercore, Dopamine Dressing, RomCom Core, Bloke Core. Each phrase alone generates hundreds or thousands of search results of garments ready to buy and ship.

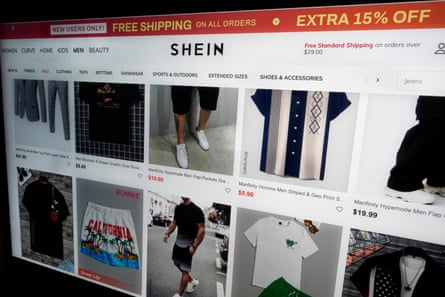

Shein is the world’s most-Googled clothing brand, the largest fast-fashion retailer by sales in the US, and one of the most popular shopping apps in the world. Its website is organised into dozens of categories: women, curve, home, kids, men and beauty, among others, though the women’s clothing section anchors the site. There are hundreds of thousands of products available, and many of them are sorted into Shein’s collections. There’s Shein EZwear, which is solid-colour knitwear and sweatpants with cutouts, and Shein Frenchy, which means delicate floral prints, lace and bows.

In the Shein EZWear collection, I find a super-short plunging V-neck dress split vertically from the waist to the hem with ruching. Long straps crisscross in a double X on the open back and cinch the waist in the front. The fabric looks like cotton jersey; it’s 91% polyester and 9% elastane (100% plastic). There are five colours available: black and brown – which are both, apparently, “HOT” – bright pink, royal blue and emerald green. The model is Photoshopped into Jessica Rabbit proportions, with a tiny waist, wide hips and enormous breasts, her collarbones jutting out several inches. She is tan and hairless, and she is headless. She poses in front of a bedroom set, crumpled white sheets, ivory macrame pillowcases, and drawings of flowers framed in gold. We see her as she sees herself in the mirror, angled to get a look at her whole outfit. She wears white sneakers, a miniature pink handbag and a gold necklace with a tiny red cherry charm. Below, under “customers also viewed”, a sea of identical headless models in black dresses reads like a Captcha image.

I began to fall in love with clothes in 2005, when I was eight. I wanted to wear bright colours and bold patterns that could make people smile or be drawn to my otherwise shy self. I was learning, rapidly, that clothing could do the work of personality. I went shopping with my mom at stores such as the Gap and Banana Republic, but their offerings were stoic and muted. Zara, which opened its first LA store that year, was different: its enormous glass windows were full of trendy, fun pieces and teenage looks I dreamed of wearing.

When the Swedish brand H&M opened its first LA store the next year, I was primed for it. Here were the brilliant Zara clothes at child-allowance prices. I could take a $20 bill and come back from the mall beaming with a new outfit. I never thought about why the clothes were so cheap. I just loved that they could be mine.

And then I started to read more about clothes. I was enthralled by Style Rookie, Tavi Gevinson’s fashion blog. Tavi was my age and clothing-obsessed: her careful outfits were brilliant, multilayered collages of hand-me-downs, vintage finds and even objects such as guitar straps and children’s toys. I checked her blog daily, hoping for a new after-school dispatch of her Outfit of the Day. Style Rookie linked me to other blogs, and those blogs linked me to even more blogs: an ecosystem of fashion-loving young women, all posting elaborate, outlandish outfits. The fashion bloggers taught me about designers and runway collections, both contemporary and historical. I learned about styling, and the many, many ways a single piece can be reworn and recombined. I learned about thrifting and the endless bounty of goodwill bins.

In an attempt to wear clothes like those I’d seen on niche blogs, and with the help of even more niche blogs, I learned to sew. I coveted things I couldn’t afford – designer pieces I’d learned about on the blogs and rare 1960s vintage dresses with frilly hems – so I constructed analogues. It was time-consuming, I learned, to make something, and much more time-consuming to make something well.

By the early 2010s, the phrase fast fashion had been in circulation for a couple of decades, but had yet to acquire a widespread pejorative connotation. Though the 1990s saw the rise of a robust anti-sweatshop movement, the public consensus a few decades later was that fast-fashion stores were a different kind of retail experience, but not necessarily an evil one. H&M and Target were producing highly coveted designer collaborations with Alexander McQueen, Rodarte and Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons. Cheap clothing chains were exploding all over the country. News articles about the industry’s growth were positive, or at least neutral: accessible, stylish clothes were seen as a common good. The rare hesitations – like a 2008 New York Times article that considered “a feeling of unease at how the ultra-cheap clothes can be manufactured” – were afforded significantly less space.

The sewing bloggers, however, were already voicing their concerns. They called out the chains who ripped off styles by independent designers to a comically exact degree (clothing isn’t copyrightable under current laws, so the chains got away with it). I learned that any new clothing I could ever afford would be far from a fair price for all the skill and labour involved in its creation. Garment workers were toiling in bleak conditions, working 16-hour days, seven days a week for pennies in crumbling factories full of toxic chemicals in China, India and Vietnam; cheaper price tags pointed to worse conditions and, unimaginably, even worse pay. I also learned about the environmental costs – the oil to run the equipment, the factory pollution spewed into the air, the energy required to fly and ship garments around the globe, and the billions of pounds of fabric waste destined for landfills, never to decompose.

In 2013, the Rana Plaza garment factory collapsed, killing nearly 1,200 low-wage garment workers. The eight-storey complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh, had manufactured clothing for Walmart, JCPenney, Primark and Mango, among others. The collapse was a tragedy – and a media tipping point. For a while it really felt like the realities of fast-fashion production were reaching the masses. How could anyone read about the deaths of those workers and walk into a Primark again? Wasn’t it clear that the conditions and exploitations at Rana Plaza were endemic to the entire fast-fashion industry?

For years I remained a loyal reader of the blogs. Then the bloggers moved to Instagram. But the internet was changing. The fashion girls I loved were becoming more like advertisers, tagging the brands in their outfits in every post and occasionally doing sponsored content. Instagram became like a shopping mall, adding features that allowed you to buy clothes straight from the app. I missed the uniqueness and idiosyncrasy of the blogging era. The fashion subcultures I loved were subsumed by the logic of algorithms.

Then, around 2019, the fashion internet moved to TikTok. There were new faces here: younger women more adept at producing videos than their older counterparts. They had ring lights and smooth, cherubic faces seemingly made for the camera. When I joined TikTok in late 2020, the algorithm quickly directed me to them. Every day I opened the app and watched “Get Ready With Me” (GRWM) videos, the contemporary iteration of the bloggers’ Outfit of the Day posts. I watched “content creators” review jewellery brands and makeup looks, or pose cheekily on a New York sidewalk for a quick “fit check” (always kicking up a heel to show off their shoes).

TikTok was where I learned about Shein. For a while my For You page served me videos of sustainable fashion influencers decrying Shein’s labour and environmental practices. Of all the fast-fashion producers, Shein has attracted the most criticism. It has removed products from sale after toxic chemicals were found in them; it produces fabrics such as spandex that never decompose (at this point an image would flash across the screen: a mountain of discarded clothes in the Chilean desert so large it is visible from space); workers in some of its factories earn $556 a month to make 500 pieces of clothing every day, work 18-hour days, and use their lunch breaks to wash their hair – a schedule they repeat seven days a week with only one day off a month. A more nuanced TikToker might point out, briefly, that conditions in Shein factories are not necessarily unique, or that focusing on suppliers – rather than the larger systems of western consumption and capitalism that create these conditions – is a fool’s errand, but the platform isn’t built for that kind of dialogue. I clicked on the comments and invariably read ones with several dozen likes saying: “I’m so willing to die in Shein clothes.”

Before long I was watching Shein hauls. There are millions of them – the tag #Sheinhaul has been viewed a collective 14.2bn times on TikTok. In each haul, a woman rips open a plastic bag filled with smaller plastic bags filled with small plastic clothing. Sometimes the woman holds up each garment and narrates its merits, but often the clothes are disembodied, laid flat on a floor or a bed in an accidental stop-motion animation. Sometimes a haul is five pieces, and sometimes it is too many pieces to count. The garments appear and disappear in seconds, edited to the beat of a trending song. Rarely do we see the clothing on a body.

It was uncanny to bounce between videos: here was a girl showing off her new halter, here was another girl giving a litany of reasons why it was unconscionable to buy clothes for so little money. Didn’t these TikTokers hear one another? But then again, how could they? “This is what we keep missing here in the whole conversation about sustainability in the industry,” Nick Anguelov, a professor of public policy from UMass Dartmouth, said to a Slate journalist writing about Shein in June. “We keep failing to understand that our customers are kids and they don’t give a fuck.”

In 1963, Amancio Ortega Gaona started a business making housecoats and robes in the small Spanish city of A Coruña, where he had grown up and trained with a local shirtmaker. When he set out on his own, he predicted that rather than designing new clothing styles, a better way to make money was to ascertain precisely what high-end designs people wanted, copy those designs with inexpensive materials, and sell them at lower prices.

By then ready-to-wear brands were already outsourcing manufacturing to factories in Asia, where labour was cheap. At the top of each season, those factories would send large batches of completed orders to stores. It was a way to save costs, Ortega knew, but it meant inventory was at the mercy of manufacturers thousands of miles away. Ortega wanted to be nimble – so he decided to manufacture locally.

When Ortega opened his first store, in 1975, he called it Zara. From the start, it was an enormous success. Zara designed all its own clothing, placed small inventory orders at its local factories, and shipped products to stores within five weeks – significantly faster than the traditional design-to-retail timeline of six months. The managers reported sales data and more amorphous information such as “buzz” around particular products or other in-store customer reactions. Limited stock also created powerful demand; on the flip side, there would be a whole new range to buy in a few weeks – encouraging shoppers to quickly return to Zara’s stores. Fashion, for the first time, became fast.

Zara was a colossal, world-altering success. By 2011, Zara had stores on every populated continent. Today Zara produces 450m garments a year, generating an annual revenue of $26bn. The 20,000 garment styles Zara produces every year can move from concept to product-for-purchase in one of the company’s 3,000 retail stores in as few as 15 days.

Zara arguably set the blueprint for every major fast-fashion brand. But unlike Zara, brands such as H&M, Forever 21 and Asos do most of their production in China, Bangladesh and India, where labour is wildly cheap and the factories are far from their headquarters.

The rise of Shein marks a new era in the fast-fashion industry. The company produces garments at a rate incomprehensible to its predecessors, all of which were already producing a world-historical quantity of products at an incredible clip. In a recent 12-month period in which former fast-fashion giants Gap, H&M and Zara listed 12,000 to 35,000 new products on their websites, Shein listed 1.3m. Last year, the company brought in $22bn in revenue, a staggering statistic for a corporation that has been around in its current form for less than a decade.

Shein launched as SheInside in 2011 in Nanjing, China. Its founder, Xu Yang-tian, had no experience in fashion. He was a specialist in search engine optimisation. SheInside started out selling wedding and evening dresses to US-based and English-speaking shoppers and soon expanded into general womenswear. In 2014, SheInside started to design and manufacture products, and soon began establishing its own supply chain in Guangzhou. It transformed itself from an e-commerce website into a clothing brand and, within a year, changed its name to Shein.

Shein spent years cultivating relationships with producers. At first factories were reluctant to take orders from the company – like Zara, Shein wanted to place orders of just 100 pieces and scale up or down depending on demand for each style, which was risky. But Shein rapidly developed a reputation for paying factories on time, an industry rarity that generated powerful goodwill. Shein quickly developed the hi-tech version of Zara’s small-order, quick-response production method, in which store managers collect data about sales and customer preferences and report it back to the factories to adjust production runs. The company’s custom-built production software identifies which products are selling well on the Shein website and reorders them from manufacturers automatically. It’s a flexible system built for the internet’s microscopic attention span: all products are tested on Shein’s website and app in real time.

Shein works both with “original design manufacturers” that design and produce the clothes on the Shein website, and “original equipment manufacturers” that make Shein-designed clothing under the watchful eye of the brand. By some reports the company has close to 6,000 factories making its clothes, many of which are in a single geographic area.

On the marketing side, the company was early to the influencer game, sending promotional products to bloggers as far back as 2012. Shein advertised on social media and relied on digital word-of-mouth to move merchandise – obvious strategies a decade later, but novel ones at the time. Today, Shein contracts thousands of influencers around the world, sending them enormous amounts of free product in exchange for social media posts. In turn, influencers earn commissions on the Shein products sold with their unique discount codes; some earn a flat-rate fee from the company, too. As a result Shein is the most talked-about brand on TikTok, Instagram and YouTube, the centres of the gen Z internet.

In some respects, Shein resembles Amazon more than a fast-fashion retailer: its catalogue of merchandise is so expansive that it functions more like a search engine than a clothing store. It maintains no permanent physical storefronts, and as such is unconstrained by square footage, retail labour or rent. Low overheads mean low prices, and Shein is the place for the cheapest clothes in the industry. Even the user experience is similar, in the way that both Amazon and Shein feel junkified: pages are unpolished, with varying product listings and completely unpredictable product qualities. Shein is a microcosm of the internet and a sibling of the internet’s other most powerful retailer: weird, clunky and seemingly thrown together.

A friend texts me screenshots of a Shein sweater vest she ordered last year. It’s cropped, with bands of cream-coloured ribbing around the neck, armholes and waist, and patterned with brown argyle diamonds. On the website, the sweater is placed into a scene with black loafers and a paper with text in French, evoking an unimaginative fantasy of European life. It casts a fake shadow. “It was not a real garment,” my friend says. She discarded the vest as soon as it arrived. “The pattern was printed on. You could not wear it in public.”

I search for the vest on the Shein website – it takes me a few tries to find the right listing among dozens of similar products – and look at the reviews. Thousands of customers leave five stars for the vest. “The item is exactly like in the photo and the material is a bit thin but I like it,” writes one girl. In her three attached photos, she covers her face with her phone. On screen, at half an inch wide, the sweater looks cute and comfortable, a thing designed to be worn in photos, sold on the basis of a largely computer-generated image.

The reviews are typical for a Shein item. Customers add photos of themselves, holding phone cameras to mirrors to capture their outfits. Every image is a selfie. “OBSESSED!!!!” they write, adding: “(likes are appreciated <3).” Likes are a currency, convertible into Shein points. Posting a review earns five points, a review with pictures earns 10, and a review with size information earns an additional two. Every dollar spent on Shein earns a point, and every 100 points turns back into a dollar. The economy flourishes: “Please like I need points to buy this in a different colour.” “Please LIKE MY REVIEW and help your broke girl out. (Sorry I can’t post wearing the items- broke shoulder – thanks for understanding!)” “Absolutely in love with these pants wearing them right now super cute please like I’m broke LOL.” “(pls like I need points).”

Other customers focus on the quality of the garments. Pieces are “surprisingly good”, “really well made”, “not see through”. Texture points to quality: “Feels nice for the price.” “Doesn’t feel cheap.” “Im autistic and i hve sensory issues and if actually doesn’t itch at all.” They read like pre-emptive defences, or maybe expressions of genuine surprise.

Only occasionally are customer reviews critical. A reviewer docks a star on a lilac off-the-shoulder bodysuit for the item’s shipping condition: “VERY WRINKLED ON ARRIVAL.” A cardigan review reports, distressingly: “texture was surprising.” But nearly every one, regardless of tone, is five stars. A perfect rating for a “fairycore” black ruffled dress says: “The material kinda sucks … And it kind of makes a lot of noise when you move. Almost immediately the top Lacey pattern snapped off.” A pink dress is “cute but looks kind of cheap, and idk where I would wear it to”.

Taken en masse, there’s a feeling of camaraderie found in the reviews, of people sharing tips, suggestions and advice. But sometimes, the advice is bot to person. A comment on a mint-green dress: “Nice one and beautiful size size and beautiful dress size size and beautiful beautiful size and beautiful dress size size and beautiful dress nice size and beautiful dress size size and beautiful dress dress and dress dress size size and beautiful dress.”

Other reviewers seem somewhere between human and machine. A commenter copies the entire first verse of Justin Bieber’s Sorry into a review for a multicoloured midi skirt with a thigh slit. (No information about the skirt; five stars.) One customer appears to paste a high-school English paper (strained poetry analysis) into the comments of a raglan sleeve letter jacket tagged as “gorpcore”. Another describes the smell of her new jeans as “normal”. I read three sets of five-star reviews posted by the same woman under a listing for long-sleeve crop tops in a variety of colours: “I absolutely love these Shein tops!! Very short though!!!!!” “I absolutely love these Shein tops! Very short though!!” “I absolutely love these Shein tops!!!!” In one of them, the shirt in the photograph is not of the product being reviewed. Seven hundred and eighty-eight customers mark her reviews as helpful.

Away from the computer, I began to look more closely at strangers’ outfits, trying to imagine where they had come from.

The neon-green bikini my friend from high school wore once on Instagram, never to be seen again – Shein? (OK, almost definitely.) But that sweater, which looked suspiciously like a minor designer piece I saved up for months to purchase for myself – was that Shein, too? Was the whole world shopping at Shein?

I started reading more about the accusations against the company. Investigative journalists with Channel 4 found employees at Shein factories working 18-hour days, making poverty wages at less than 4¢ a garment. (Shein said it was “extremely concerned” by the claims and launched an investigation.) But wasn’t that the case at fast-fashion factories all over the world? In 2022, Bloomberg News commissioned laboratory tests of Shein clothing and found that some of it had been made from cotton sourced from the Chinese region of Xinjiang, where Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities pick cotton under conditions of forced labour. The US has banned imports of all goods produced in the region, which would in theory subject Shein shipments to detention – but because of certain shipping loopholes, most Shein packages slip past customs regulators. Still, Shein has claimed it does not contract with manufacturers in Xinjiang, and their own analyses show most of their cotton is sourced from elsewhere, but perhaps it’s all a moot point: only 4% of Shein’s products sold in the US are made of cotton anyway.

When I started to feel sanctimonious about not shopping at Shein, I remembered that the “better” ready-to-wear stores, where I sometimes buy socks and T-shirts, aren’t offering products at a much higher quality – and their factories aren’t necessarily more ethical, either. Even luxury brands sometimes rely on exploited workers to produce their extraordinarily expensive clothes. Overconsumption exists across the price spectrum: Americans buy an average of 68 garments a year and wear each an average of seven times before discarding. We have less money to spend on clothing and quality is more expensive than ever, but clothing prices have stayed the same, thanks to more exploitative labour practices and lower-quality materials masquerading as efficiency and innovation. I can’t justify the desire to consume and collect more dirt-cheap garments than one could ever sustainably wear, but I know the desire to wear just the perfect outfit and the rush of serotonin that comes from buying an exciting new piece of clothing. Many people think of fast fashion as their only option.

Shein didn’t invent the market or the cultural context for fast fashion, and some believe it is unfairly maligned as its worst offender. At least some of Shein’s reputation as exceptionally bad is rooted in anti-China sentiment, as the fashion scholar Minh-Ha T Pham has argued. While we shouldn’t make the claim that Shein is ethical in any way, Pham says, it’s likely that the company would be celebrated as an innovator if it were based in the US; that our prejudice against the brand is related to the fact that Shein is Asian-owned.

Shein is now considering an IPO in the US and has hired its own Washington lobbyists to push back against the forced-labour claims. It says it “aims to reduce supply-chain emissions by 25% by 2030”. It has also gone on a media blitz, and even sent a handful of TikTok influencers to what they claimed was “one of the main supply manufacturers for Shein”, only to have the campaign backfire massively when a video tour of Shein manufacturing centre by a self-described TikTok “confidence activist” was pounced on by critics. (“They showed you what they wanted you to see,” went one of the outraged responses.) It’s as if Shein is seeking a rebrand, though not one aimed at its customer base.

I can’t wonder any longer what the clothes are like in the abstract. I need to experience Shein for myself. After what feels like an hour on the site, I settle on two garments I could envision myself actually wearing, if not buying, under normal circumstances: a long-sleeve black mesh shirt for $6.37 and a strappy light-green summer dress for $8.50. My shipping is free, and I spend a grand total of $14.87. My package will arrive in two weeks. Everything about Shein moves so quickly that I’m surprised by the relatively long shipping time until I remember that my package is being sent 8,000 miles from Shein’s distribution centres in Asia.

Nine days after placing my order and four days ahead of schedule, my shipment arrives. Inside the shipping bag are two smaller frosted ziplock bags with black zippers and a large Shein logo printed across the bottom, familiar to me from TikTok haul videos.

I start with the Shein BAE Glitter Sheer Mesh Top Without Bra. The shirt looks like the pictures: long-sleeved and made of stretchy black mesh, with glittery flecks embedded in the fabric. I’ve bought a size large, and it’s too big: the shoulder seams droop sadly off my collarbones. The elastic seams are puckered. It’s less itchy than anticipated, and the fabric is slinky and cold against my skin. I feel like a different version of myself, like the kind of girl who captions her Instagram posts with the sparkle emoji. I imagine wearing my new Shein BAE Glitter Sheer Mesh Top with a bra and black jeans, drinking with friends. I imagine looking across the room and seeing a girl dressed nearly exactly like me, but she’s wearing the Shein BAE Lettuce Edge Glitter Mesh Top Without Bra, instead.

My other new Shein garment is both uglier and more distinctive. It’s the Shein Unity Tie Shoulder Split Thigh Cami in lime green. The garment inside the ziplock bag is crumpled around a small square of tissue paper, which serves no discernible purpose. I’m surprised to see that neither the dress nor the shirt has any paper price tags attached: there’s nothing to indicate that the clothes are brand new beyond their intense chemical smells. I ordered this dress in a medium, and it barely pulls over my hips. The fabric is a medium-thick stretch knit similar to a heavy T-shirt. Thin, wavy folds have been stitched into the material, creating a ruched effect. The texture is unusual, but almost a nice detail. (My friend takes one look at the dress and describes it as having both the look and feel of a ribbed condom.)

Fully on, the dress barely covers my chest – I can’t lean, bend or jump without flashing my reflection, and any large steps cause the super-high thigh slit to rise dangerously close to my ass. Standing still, though, I look good: sexy, trendy, youthful. But I quickly discover that the dress is too tight to pull over my head. How did I get in here? I shimmy and curse until I’m able to wrench the dress off me, where it springs back, tauntingly, to its original shape. Laid flat on the floor, the form is like a cartoon body: a perfect hourglass, smooth and dramatically curving.

My new Shein clothes lie in a crumpled pile on my living room floor for a week. I can’t figure out what to do with them. Neither garment is particularly wearable, but the hassle of returning the pieces (or donating them, or selling them to a thrift store) seems absurd when they cumulatively cost me less than $15 to begin with. The idea of folding them up and placing them in my dresser alongside my other clothing feels defeating. I think briefly about trying to sew them into something new, but again – the hassle. Mostly I don’t think about them at all. The garments cost so little that I don’t feel pressure to make them fit my wardrobe, or my life. I’ve already forgotten why I wanted these particular clothes in the first place.

A longer version of this article appears in the current issue of n+1 magazine