Five miles deep in the backcountry west of Crested Butte, Jeff Banks stopped the group. The 49-year-old IFMGA guide was leading me and five other skiers around Kebler Pass. He had asked us to set the skin track, and we were aiming for a benign-looking rollover. But avalanche danger was “considerable” and the slope in front of us was roughly 36 degrees, in Banks’ estimation—steep enough to slide and large enough to carry a skier.

“We’re not going to cross under that,” Banks said.

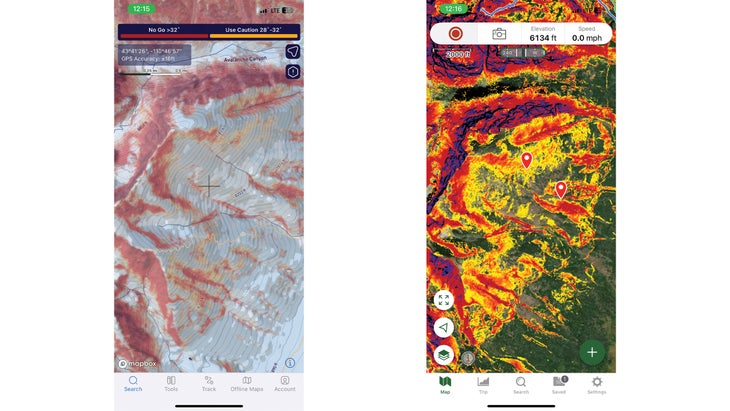

Instead, he gathered our group, pulled out his phone, and booted up AspectAvy, an app that he and a team of developers recently launched in hopes of simplifying users’ decision making and making backcountry travel safer. AspectAvy marked the hill as no-go terrain, coloring it red. Banks was also able to use the app’s runout calculator to demonstrate that, if the snow on the hill above us broke loose, it could run far enough to catch our group.

Banks started developing AspectAvy over a decade ago, after a guiding accident in Europe. He and his clients were traversing a steep face near Sulden, Italy, that other guides and skiers had been crossing for days. But when he and his team crossed the slope, an avalanche broke and carried them nearly 1,800 feet and over three cliff bands. Fortunately, they walked away unscathed, but the experience underscored something Banks had long understood: backcountry skiers, even professionals, don’t make the right decisions 100 percent of the time.

“I’ve been privileged to have the best training and mentorship and exams the country can provide,” Banks says. “And it’s not good enough. The system just isn’t working. If all the pros who crossed the slope for days got it wrong, what are we doing?”

Banks wanted a tool that could help change that. AspectAvy was his answer.

The app’s central feature is its identification of “no-go” terrain, which an algorithm colors red and overlays on topographic maps. The app scrapes data from regional forecast sites and uses it to estimate the safety of a slope on a given day using three variables: the forecasted avalanche danger, slope angle, and the presence of old snow problems, like persistent weak layers. After studying eleven years of avalanche fatality data, the app’s creators determined that these three factors could help them create buffers intended to keep skiers safe.

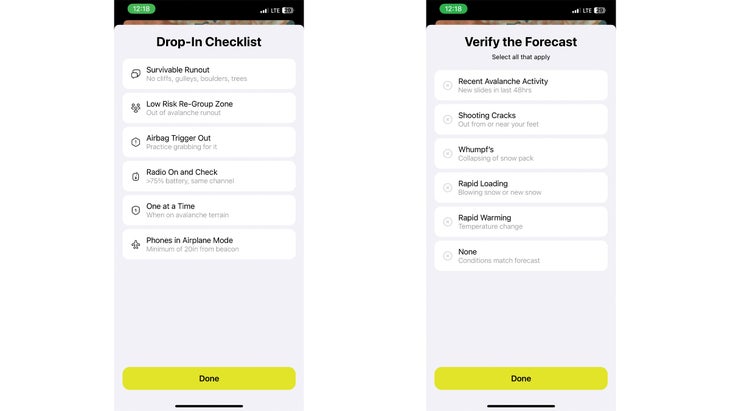

The app also has the aforementioned runout calculator, which is fixed based on slope angle and doesn’t change based on the forecast, as well as checklists for skiers to use at the trailhead and before dropping in, with reminders to check their beacons, ski one at a time, and always keep eyes on the person skiing. There’s a slope angle calculator, and a tool to help skiers verify the local forecast and elevate it if unexpected, dangerous conditions arise. Skiers can note recent activity like shooting cracks, whumpfs, rapid loading, or rapid warming, after which the app will raise the danger rating and shade a more conservative slice of terrain in “no-go” red.

Banks compares each app feature to a slice of Swiss cheese, where holes represent a margin of error. Add more Swiss and the subsequent slices should cover the prior holes. By itself, AspectAvy’s “no-go” slope angle shading might not keep a skier from making a dangerous decision, Banks says. But he argues if you layer AspectAvy’s other tools on top, each additional layer should help prevent skiers from getting into trouble, or dying.

“It’s a risk treatment,” Banks says of the app. “It’s not a mapping app. It’s preventative avalanche safety gear. It’s designed to keep you out of avalanches and still provide good riding.”

Not all avalanche professionals agree. And that’s made the app controversial in ongoing conversations about how to prevent avalanche deaths in the United States, where the COVID-19 pandemic drove about a million more skiers than usual into the backcountry, and where an average of 27 people die in avalanches annually. For forecasters skeptical of AspectAvy, they have a metaphor of their own: One about pedestrians and their phones.

“You can engineer your way into a million things but you still have to look both ways before you cross the street, otherwise you’ll get run over,” says Simon Trautman, director of the National Avalanche Center.

Banks, for his part, thinks the app’s buffers are quite conservative. If forecasters have determined that avalanche danger is low in a given zone, users will be advised to keep it under 40 degrees. If the rating is moderate, the app recommends keeping it under 35. Moderate with an old snow problem in the forecast—a danger rating forecasters informally refer to as “scary moderate”? Keep it under 33. Considerable? Stay under 30. At high or extreme danger the app says to avoid the backcountry altogether. All of those thresholds are based on fatality data. In AspectAvy’s dataset, nobody has died skiing a slope under 40 degrees at low danger, or riding a slope under 30 degrees on a considerable day. Banks and his team also programmed the app to start shading no-go terrain a few degrees early. So, on a considerable day, it might shade terrain as shallow as 28 degrees as no-go.

At scary moderate and considerable, AspectAvy recommends that skiers and riders avoid runout zones because remote triggering is possible. The app also always shades terrain above 40 degrees as no-go, because skiing in terrain that steep is never “low-risk skiing,” Banks says.

“That doesn’t mean they can’t choose to do it,” Banks says. “Think of it as a speed limit. You may choose to go over the speed limit, but that’s on you.”

The idea that a forecast combined with slope angle can give you a concrete yes-or-no answer about whether a slope is safe to ski may, however, oversimplifies the process of navigating avalanche terrain, Trautman says. “That’s really one of the key problems,” Trautman says of AspectAvy. “The hazard is not based on slope angle. Some days it is, some days it isn’t. A lot of different things go into those hazard assessments. They’re a subjective bucketing of something that exists along a continuum.”

Danger ratings give skiers and riders an idea of what terrain could be dangerous to ski and, inversely, what terrain could be safe. But they don’t give slope-specific advice—and they don’t guarantee that slopes are safe. It’s up to backcountry skiers and riders to be educated, verify the forecast, and keep their heads on a swivel to identify not only unpredicted hazards like wind slabs, or surprise warming, but also the best skiing conditions.

“Anybody that says that they can simplify something as complex as either the avalanche phenomenon or decision-making when you’re actually in avalanche terrain—I think we should be skeptical of claims like that,” Trautman says. “Because it’s not simple. It’s incredibly complex. And like it or not, our own brains need to be part of it.”

Beyond that, the in-app shading delineating safe and unsafe terrain could be misleading. Unlike Gaia and CalTopo, which can show users all avalanche terrain at all times, the shading in AspectAvy just delineates the terrain that the algorithm deems “no-go” that day. On a low-danger day, the app wouldn’t mark the 36-degree rollover on Kebler Pass as avalanche terrain. But a wind slab could still lurk on that slope.

Trautman also takes issue with the way the app gathers data to identify old snow problems. Since forecasters describe old snow problems differently, AspectAvy’s developers have identified key terms, like “facets,” that professionals typically used to identify those problems. If any are in the forecast, the old snow warning goes off.

Forecasters will occasionally identify only one avalanche problem, like a wet slab, but discuss other issues, like faceted weak layers. In that situation, the app would identify an old snow problem, even if it’s not in the forecast.

For example, on February 2, when I spoke with Trautman, AspectAvy was calling avalanche danger “scary moderate” in a forecast zone around Mount Baker, indicating there was an old snow problem. But the local forecasters at Northwest Avalanche Center hadn’t identified an old snow problem. They had identified a wet slab problem.

Trautman wasn’t sure how AspectAvy came to its conclusion, which made him question whether the team was “following a rigorous, transparent, or effective scientific process.” Banks says the result that day was likely because of how AspectAvy scrapes forecast websites. On that day, however, the forecast didn’t obviously mention a faceted layer.

The same day, AspectAvy also told skiers to avoid runout zones. But the app typically doesn’t mark runout zones as “no-go” terrain if they’re not steep enough to slide by themselves. Trautman worries that not labeling runouts as closed terrain could falsely indicate that people can safely ski an area that’s not safe—since the app’s runout calculator must be toggled on and off for each individual slope, and because the app’s core feature is identifying “no-go” terrain.

The app has a handful of other concrete limitations. For one, it’s only available on iPhones. It also only operates in places where there’s available LIDAR, highly accurate elevation data that’s collected from an airplane and used to calculate slope angle. In the Teton range, for example, AspectAvy works in Grand Teton National Park. It doesn’t work on Teton Pass, where LIDAR isn’t available. It only works in places with avalanche forecasts, too.

Despite his concerns, Trautman doesn’t want skiers to avoid the app altogether. Rather, he wants them to approach it cautiously. “Anyone using it should seriously question whether the tool is working the way they think it works,” Trautman says. “I do think it’s important to be very honest about it, because this thing is getting a lot of press.”

Other avalanche professionals simply see AspectAvy as just another helpful tool for skiers. Angela Hawse, former president of the American Mountain Guides Association, says she understands Trautman’s hesitation. “But I think that skepticism without a little bit of optimism and the potential utility of it is short-sighted,” Hawse says. “It’s a tool in the kit that helps with decision making. Especially when, as we know, in the field, things aren’t always straightforward.”

Hawse thinks AspectAvy will make people more conservative, if anything, and sees the app as a digital equivalent of a morning guides’ meeting, where experts talk about conditions and identify open and closed terrain for the day. In some ways, Lynne Wolfe, editor of The Avalanche Review, about AspectAvy agrees. She thinks the app might help skiers and riders select an “appropriate mindset,” providing a general indication of what terrain is safe to ski. “But on-the-ground terrain and conditions should trump,” Wolfe says.

The app may be particularly useful in tour planning and checking yourself before you drop in, says Frank Carus, director of the Bridger-Teton Avalanche Center. But Carus, who admitted that he’s old school and a fan of paper maps, was also concerned that the app could create a new heuristic trap, something akin to a digital expert halo, wherein skiers and riders become overconfident in the app.

“If the app makes some part of the process a little simpler, and that helps you devote more time to your surroundings, maybe that’s good,” Carus says. “But any good driver’s ed instructor tells you to look both ways after the light turns green because somebody could be running a red light.”

In Banks’ mind, that thinking is simplistic. He would argue that the app, with its slope angle meter, forecasts, and checklists are the reminders to look both ways before pulling into the intersection.

“The risk junkies who stand at the top of the bowl on a considerable day, they’re going to go anyway. But there are a lot of smart people who are not risk junkies and still get smoked,” Banks says. “This is going to do the greatest good for the greatest number of people.”

That’s a good pitch, but I do think forecasters’ concerns are legitimate. I’m an avid backcountry skier, based out of Jackson Hole, and I’ve used the app to get an idea of what terrain should be off limits in Grand Teton National Park. But that doesn’t mean I take what it says at face value. The app’s recommendations, for me, are just that: Recommendations. Even when skiing terrain I’m familiar with, I toggle AspectAvy and Gaia, my app-of-choice, to double check avalanche terrain that AspectAvy doesn’t always identify.

I don’t, however, rely completely on either app. Instead, I read the avalanche report every day and, in the field, check for surface instabilities, and dig pits to verify the forecast. Which is all to say—I’ll take Aspect Avy up on the offer of extra Swiss cheese. But I’ll also make sure to look up from my phone.