I WAS TOLD that He would come.

We were a few hours into Man Camp—an evangelical men’s retreat in the OhioRiver Valley—and this promise was part of the level setting that Tyler, our ball-capped and rosy-cheeked group leader, thought we needed to hear. “You shouldn’t expect to shift all your perspectives on life in 48 hours,” he said with the buoyant enthusiasm of a radio DJ. “But you should definitely expect God to show up.”

I saw nods among the dozen and a half other faces lit by campfire. Our group consisted mostly of first-timers in their 20s and 30s from all over Ohio. Out in the darkness, there were nearly 2,700 other Jesus-loving dudes in 279 groups who’d come from as far as Mexico, Canada, and Ghana to camp on the 431-acre property.

Due to the BYO-Everything nature of the weekend, most Man Campers looked like they’d just looted an adventure supply store: technical doodads, hunting knives, hiking boots, cargo pants, lots and lots of camo. Our group fit that mold, except that practically everyone but me wore a credit-card-sized cross around his neck that one of the guys had handmade from wood.

Having been to other men’s retreats, I expected us to kick rocks around for hours before finally opening up, but we got right into it. As a hearty flame crackled beneath a tar-black sky, two men bonded over their wives’ miscarriages. Another told us wistfully that his long-estranged father had rebuffed his attempts to reconnect. The most chilling story came from a guy who, almost two years earlier, had lost three people to suicide, including his mother. “Holy crap,” someone said. Was there anymore whiskey to drink?

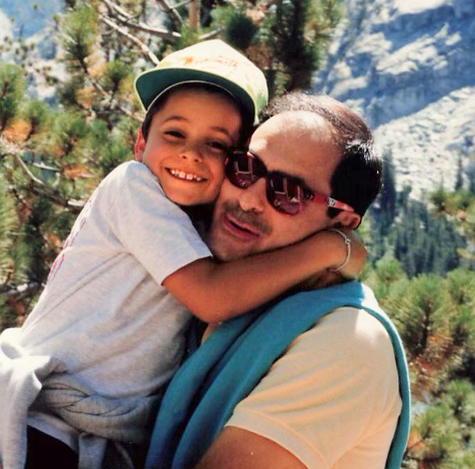

I revealed that I was going through the agonizing process of losing my dad toALS. The incurable neurodegenerative condition would soon rob him of his ability to speak and swallow. It was the uncertainty of his slow erasure that weighed most heavily on me and my mom. We’d lose a fraction of him every day until some future unknown day when we’d lose all of him.

The eldest member of my group, a 71-year-old organic farmer named Herman, handed me his cross. “I have felt in my heart that I needed to give that to you for this weekend,” he said. I sensed that he wanted me to put it on. Instead, I discreetly slipped the object into my pocket.

OFFICIALLY, I’D COME to write about Man Camp as one of the latest examples in a tradition of evangelical men’s retreats that combine macho activities with the sincere pursuit of God.

The event, which costs $150, is the brainchild of Brian Tome, 58, the square-shouldered and silver-tongued senior pastor of the Cincinnati-based Crossroads Church (the fifth-largest church in the U. S.). Man Camp, which promises to “destroy your spiritual comfort zone,” is a legal-vices-welcome weekend. (When I first encountered Tome the day before, during setup, he greeted me with an easy gaze and a Coors-and-cigarette combo in hand.) In addition to the intense fireside chats, the schedule featured a manual-labor activity, an arm-wrestling competition, and an obstacle course. There were spiritual talks and a prayer tent situated next to 80 kegs of free beer. The weekend culminated with baptisms in an uninviting cow pond.

I’d arrived in Ohio at a point in my life when I was more spiritually open than ever before. My parents are lapsed Catholics, so I’d adopted an agnostic lifestyle. But my dad’s 2022 ALS diagnosis had kicked up all kinds of existential questions about life, death, and his place in the much-contested beyond. I’d also just crossed into my 40s with a profound sense of being stuck. With no kids, I’d been trying to achieve my way out of feeling empty. (Never a great strategy.) Therapy was helping, but my gut told me I needed something bigger to overcome my soul-deep malaise.

That’s not to say I was fully prepared to accept Jesus into my heart. My friends inLos Angeles have their own biases against Christianity. Most of them are culturally Jewish or comfortable only with commerce-led, noncommittal spirituality: new-age self-help books, Transcendental Meditation, psychedelic trips, yoga retreats. BeforeI left for Man Camp, I jokingly asked my wife—an atheist from Sweden, one of the least religious countries on earth—what would happen if I came back converted. “I’d divorce you,” she said in a ha-ha-but-maybe-I’m-not-really-joking kind of way.

All of that was running through my mind on Friday night when that cross landed in my hands by the campfire. I wanted to arrive at a greater sense of peace with everything happening in my world. But I wasn’t quite sure what that looked like, or if I was comfortable with what it might take to get there.

THE NEXT MORNING, our group headed to the center of camp for the weekend’s first spiritual talk. Along the way, I spotted a group of dudes chopping wood with fluid competency and then another attempting to lift a set of Atlas stones. One campsite flew an “Easter Grizzlies” flag—apparently a reference to Tome’s suggestion one time that the holiday’s symbolic bunny be replaced with something more masculine, like a bear.

We made it to the big tent, which looked like it could house a circus. It had metal pillars as thick as tree trunks and a platform stage with a maze of musical equipment, speakers, and amps. Despite its size, it struggled to contain the swelling mass of men, and we had to find a spot outside.

Two burly Man Camp volunteers kicked things off by leading everyone in a grueling session of pushups and squats. I saw no one abstaining from the grunt-inducing activity, including a withered gentleman who had to have been 80-plus.

Then the house band, Bloodbrother, played rock-infused worship music. “Come like a FLOOD . . . like a FIRE. . . HOLY SPIRIT COOOOME!” the frontman wailed. Thel yrics were projected onto the underside of the tent roof, and men raised their hands and swayed like cornstalks, singing loudly. Many had tears in their eyes.

Suddenly, Tome appeared onstage wearing an orange anorak and a black cap

with a crosshairs logo for Buds Gun Shop & Range. He quieted the music and asked if anyone was feeling open to Jesus in new ways. Men began to rise from their seats one by one. When about 30 were standing, Tome pumped his fist like a proud football coach and bellowed, “FUCK YEAH!” into the mic. He quickly added it was his first time dropping the f-bomb onstage in a godly context, but I didn’t think so. The moment ended sweetly, with the seated men standing and laying their hands on the shoulders of the attesters, forming little huddles.

Earlier, Tome had told me that he and Judd Watkins—the event’s stocky cofounder, who roamed the grounds in head-to-toe camo—had come up with the idea for ManCamp on a 2014 adventure motorcycle trip with buddies. Over fireside beers, they’d lamented the state of male friendship and decided to help men experience what they had: the great outdoors; activity-based bonding; the thrill of the unknown; and, of course, God.

In his view, Man Camp was critical considering the country’s problem with male loneliness, a topic he returned to during his talk that morning, calling it the“greatest epidemic of our time.” Before the trip, I’d read The Five Marks of a Man,Tome’s 2018 book on masculinity, and found it a bit generic. (Men should “work,” have “a vision,” be “protectors,” etc.) But onstage, he was a charismatic presence with a habit of delivering a serious point and then quickly releasing the tension with a comedic flick of the wrist.

“Men are not well,” he said, citing statistics as easily as passages in the Good Book.Men are about four times as likely to die by suicide as women and nearly two times as likely to battle with alcohol or chemical-substance abuse. Here’s a gnarly one: About15 percent of men say they have no male friends.

“I hear guys say that ‘I’m sort of a lone wolf,’” Tome said. “My response is normally ‘You mean you’re small, weak, and going to die soon?’” Laughter rippled through the crowd.

The quip made me think about my dad, who stopped confiding in other guys decades ago after feeling Judased by a close male friend. Any community he joined was strictly for professional reasons. He remained well-liked in social circles managed by my mom, but he offered his secrets only to her. No therapist, either.

He’s told me he regrets this kind of stubborn individualism. And so I’ve worked hard to do things differently—opening up to close buddies, sitting in men’s circles, and even starting one once. But over time, groups disband, friendships fizzle. I’ve often wondered why I let that happen—sometimes worrying I’ll never overcome my anti-joiner instincts and other times telling myself I didn’t have a broader or lasting reason to stay.

There in the audience, I thought of something Tome had said to me over the phone before the event: “[Man Camp] is a failure if guys don’t sense a connection with other guys and with God.” Whenever the music kicked back up, men’s arms shot into the air as if seeking an upward embrace. Their bond was, first and foremost, in submitting to something bigger than any one of them.

WHEN PERFORMING, MARK Lukey, Bloodbrother’s bass and keys player, had a tendency to headbang his long dirty-blond hair. But when I’d spoken to him the previous day, before the campers arrived, he was a calm, cerebral presence.

Despite being a decade-long employee at Crossroads, he told me that he avoided the first four years of Man Camp (it’s been operating for nine) because of its hypermasculine marketing. Dudes jumping dirt bikes. Black-and-white imagery. In the early days, it had a “pseudo-militaristic” vibe.

“I don’t love the way it looks on the Internet,” Lukey said. “But I can’t deny that it gets people here wondering what they’re about.”

There’s a long history of evangelicals presenting a more muscular depiction of Christ—an effort typified by the 2001 book Wild at Heart, which has sold more than 4 million copies. For too long, author John Eldredge wrote, the church had offered a feminized vision of Jesus: “Mister Rogers with a beard.” Aggression was innate to a man’s soul, and he needed to get out in nature to rediscover God and his warrior spirit.

I’d already heard guys in my group cite Wild at Heart as an inspiration, and I knew that Eldredge had exerted some influence on Tome’s work. Or at least the Crossroads pastor seemed to be living out that same vision online.

For his 155,000 Instagram followers, Tome posts photos of himself hunting, forging rivers, and crashing motorcycles. His podcast, The Aggressive Life, encourages listeners to embrace “healthy aggression.” On his YouTube channel, Tome hosts“Garage Bible Study,” on which he preaches God’s word in the same oil-slicked space where he repairs old Jeeps.

It all felt a bit performative to me, but I also recognized that his presentation as a guy’s guy may be the precise reason that Man Campers—some of whom may worry that emotionality is a feminine trait—trust him to take them to uncomfortable interior places.

Kristin Kobes Du Mez, the author of Jesus and John Wayne—a book about the history of evangelical masculinity—says experiences like Man Camp can facilitate profound social and spiritual moments for guys. But they can also leave those who aren’t the beer-guzzling, bow-slinging type feeling inadequate as they wonder, Is this one way to be a Christian man or the only way to be a Christian man?

There were a few instances that left me feeling uneasy and thinking about the tension raised by Kobes Du Mez. For example, Tome made an onstage comment suggesting that being gay was sinful: “Tempted by a same-sex encounter? Yeah,Jesus was, too!” If Jesus could resist, then apparently so could we. He didn’t linger on the point or launch into a homophobic diatribe as some evangelical pastors are wont to do. But it was enough to invite some awkward questions: Who, exactly, was welcome at Man Camp? And what kinds of masculinity did it endorse?

Lukey, the Bloodbrother musician, told me that when a close friend who is nonbinary parted ways with Crossroads after feeling alienated, he nearly left as well.“I don’t think the Bible neatly answers the questions that a lot of Christians think it answers,” he said, referring to sexuality and gender. Lukey ultimately stayed because he believes Crossroads loves its people and, at its core, wants to help them follow Jesus in the best possible way. (In a phone call after the trip, Tome clarified that Crossroads is very welcoming to the LGBTQ+ community. Yet he’s also called the church’s position the “radical middle” and personally believes that although your sexuality doesn’t send you to hell, marriage between a man and a woman is the only sexual union celebrated by the Bible. It’s all a bit of a brain twister.)

Halfway through the weekend, I felt embraced by the Man Campers. But I knew my status as a straight married man, a former Olympic athlete (fencing), and an on-the-record reporter played some role in that. And my growing discomforts revealed as much about me as they did about Man Camp or Tome. I have a natural allergy to the whole rugged-adventurer thing. I was brought up in the city and went camping with my dad a total of once. (The first night of Man Camp, I slept in a manhole-sized puddle due to an inept tent setup.) I also live in Echo Park, a neighborhood in Los Angeles that’s home to a salon advertising “lesbian haircuts” and an independent bookstore piled high with queer literature. My own writing has supported “New Masculinity,” a feminist-influenced lens on gender that encourages a softer expression of manhood. Of course I’m suspicious of a Christian “man camp.”

But lately I’ve noticed that I’m not as sure about my feelings as I used to be. OnFriday night, Tome performed a bit about a newlywed husband coaxing his resistant, virginal bride in bed: If you want to have sex, reach your hand under the covers and pull my penis once. If not, pull it a hundred times. Heaving waves of laughter rolled over the crowd. And I laughed, too, at first. Then I immediately felt weird about it, knowing the same kind of locker-room joke told in my part of the world could invite eye rolls and perhaps even angry rebuttals about the patriarchy and sexual consent. Those critiques resonated with me, but I was growing tired of having to walk on eggshells around all these culturally sensitive topics.

I couldn’t deny that here, something freeing was happening. As one of my group members said on the first day, Man Camp is a place where we can actually be men, and it doesn’t have to be a dirty word.

WE WERE BACK in the big tent on Saturday afternoon, and Bloodbrother was playing the same rotation of earworms the crowd had heard many times already but was still very into. I caught a glimpse of Tome lingering outside, his head dropped in what I thought was a moment of

silent prayer. Then I realized he was relieving himself on the tire of a supply truck.After finishing, he took the stage and gave a talk about navigating spiritual doubt.

Did we know that John the Baptist had once doubted Jesus while in prison? (Obviously, his uncertainty didn’t last.) He also wore camel-hair robes and went commando, prompting a new operating metaphor from Tome: “You’re one of the ones that can deal with scratchy hair on your balls!”—meaning that the men should be proud of their ability to weather life’s challenges while clinging to their faith.

Tome told a story about recently losing a friend to a heart attack. One of the man’s sons said the loss felt like “losing a safety net.” Hearing the precise articulation of my own fear made my throat tighten. “When you believe in Jesus, that He is a savior, you inherently believe that [you] have a safety net,” Tome said.

With seemingly cosmic timing, Tyler—my group leader—slipped me a note with a message scribbled in all caps: “THE BIGGEST QUESTION I WOULD BE ASKING MYSELF IS: IS THIS JUST ANOTHER GATHERING OF WEAK DUDES WHO NEED A CRUTCH TO FUNCTION OR WHAT IF, MAYBE, JUST POSSIBLY, I MAY HAVE STUMBLED INTO SOMETHING REAL?”

THERE WERE MIRACLES happening in the prayer tent, apparently—visions presented, energies released, backs healed. When I arrived there late Saturday, large winged insects buzzed in the air and asperitas clouds undulated overhead like waves of foam.

Inside, I was led through trios of men seated on hay bales and camping chairs to meet my prayer partners. Scott had a dark beard and a corn-fed, 40-ish handsomeness. Adon had a wide, 30-something face and a scraggly goatee. When they asked why I’d come to the tent, I explained what was going on in my life: professional frustrations; general anxiety; and, above all, concerns about my dad. I was curious about all this Christian stuff, but I also felt a deep resistance in equal measure.

“There’s not any magic fairy dust that we sprinkle on guys,” Adon said. “All we have to offer is Jesus and the relationship He wants with you.”

Scott asked where I thought my dad would go when he died. I tried to explain that I didn’t think my dad believed strongly in an afterlife, despite several close calls with death. Notably, he’d suffered a serious stroke in his 30s, shortly after my parents got married and before I was born. I’d heard the story many times. He remembered floating peacefully up off the hospital gurney but then saw the doctors talking to my weeping mother. He decided to stay with her, floated back down, and made a miraculous recovery.

And yet my dad, a deeply thoughtful man, rarely waxed metaphysical on the topic of life after death and seemed shockingly unconcerned about the whole affair.“Throw my body in a ditch, I don’t care.”

Scott clarified his question: Where did I think he was going? Choking up, I told him that I hoped he was going to a better place, aware that this magical thinking contradicted the doubt welling up in me.

“We get a lot of folks who have Jesus knocking on their heart, but the door opens from the inside,” Scott said. I couldn’t help but think of a line by the essayist John Jeremiah Sullivan: “Faith is a logical door which locks behind you.” In other words, if you accept the terms of Christianity, your belief will then modify incoming information to reinforce itself.

For another ten minutes or so, I hesitantly expressed my doubts. Scott and Adon commented thoughtfully but ultimately soft-pedaled me Jesus as a one-item, all-you-can-eat buffet. The two men asked to pray for me, putting their hands on my shoulders and back. Scott petitioned God to make direct contact before asking for my father’s safe passage into heaven. Adon asked the same God to restore my dad to full health.

I winced at the inconsistency.

Then, for several moments, we stood in silence, the men’s hands shaking as if zapped with electricity. Afterward, they looked at me expectantly. Had I felt anything?I told them ruefully that I had not been reached.

“No sense of the spirit through all of that?” Scott asked, incredulous.

It was not the first time that weekend that men had asked to pray for me. But suddenly, I was aware of the dark chasm those prayers revealed. No matter how kind, patient, and loving the tone, they bore an instructive undercurrent, like when a kindergarten teacher sweetly rephrases a command to make a child feel that compliance was their idea. Didn’t I know that failing to accept Jesus resulted inconsequences? Didn’t I want to be saved?

I SLEPT FITFULLY that night and awoke on Sunday, the final day, with a sore throat.

Our campfire had run late, past 1:00 A.M. Libations had gone around the circle, and someone had handed me a cigar. It was the pleasant fraternal wrap-up you’d expect—good men making commitments to be better men. One guy who’d been a bit cagey at the outset said the weekend had reminded him that real friendships were possible. He’d meant it, and I agreed.

I’d told my group about my struggle in the prayer tent. While not spiritually significant, it had been emotionally helpful, I said. But I just couldn’ts wallow the pill.

“I fully respect you trying to figure something out on your own timeline,” Tyler said.

Baptisms were in a couple hours.But first Tome brought us back into the big tent to hear the guest speaker, Otis Williams, an ex-paratrooper with a compact, coiled frame and a booming voice.

“This land has been specifically purchased and developed for you to leave the shit that keeps you from advancing to the kingdom of God,”Williams shouted over aggressive, organ-heavy music.

He told the men to make a noise symbolic of their commitment to letting go of anything holding them back—doubt, fear, infidelity, sexual misconduct, gambling, addiction, drugs. A torrent of male screams ripped through the tent.

Without missing a beat, Williams started up a vociferous chant. “God. Wants. Warriors. I’m. Signing. Up,” they all repeated together.

I was well aware that every self-helpish weekend has one of these moments when participants’ demons get a “swift kick in the ass,” as Tome later put it. Still, I was compelled to spiritually steel myself against this harsher energy. It felt like Jesus was no longer knocking. He was kicking in the door.

Men began heading down to the cow pond for baptisms. Tome called the ritual the “watery grave,” a description that seemed appropriate considering the weather had turned chilly and, in the gray light, the surface of the pond was mucus green.

A few hundred men stripped down to their underwear and formed a line at the pond’s muddy ingress.

With a large audience watching from the sidelines, members of Bloodbrother—Lukey included—received men one by one in waist-deep water. Before dunking them, the band repeated in unison with the crowd: “I baptize you in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit!” Several of my group members waded in together. What was happening? I realized the event had turned into something of a baptism free-for-all, friends dunking friends and fathers dunking sons. The joy emanating from the pond was infectious. And for a split second, I felt like hopping in there myself before realizing it would be disrespectful to do so without genuine faith.

After the baptisms were finished, I found Tome at the side of the pond, where he’d been watching the scene unfold. As we hugged goodbye, he used his free hand to hold my head against his shoulder and spoke into my ear. “God,” he said, “anything you deposited in him, I pray that you help it grow.”

A MONTH AFTER Man Camp, my father lost his ability to eat and had a feeding tube installed. A couple weeks later, we could no longer understand him, and he began communicating exclusively through writing or a text-to-speech app.

One night, I visited him at home and told him about the trouble I was having finishing this article. A central thread was eluding me. Worse, I questioned myo riginal intentions. I’d convinced myself I was open to the Christian experience, but I was doomed from the start. The world I came from—progressive politics, feminist wife, skeptical dad—was too vast a moat to cross. I asked why he’d given up Catholicism, thinking we could find solidarity in our mutual doubt. “Too much punishment and purgatory,” he wrote on his little handheld tablet.

Then he shared that despite leaving his parents’ faith, he had “one-way conversations” each night with a Christian-esque God—and he’d been doing it for “a long time.”

I nearly fell off my chair.

His float-up-off-the-gurney experience had stirred something deep in him. But he never spoke of it that way, preferring his own personal rituals. I couldn’t think back on the rock concert and rah-rah faith I’d witnessed at Man Camp without feeling at least a little spiritually checked out. But perhaps this was the belief I could get behind—the kind steeped in a private stillness, far from the fervor of a crowd.