Children, like adults, want to be fair and kind. At the same time, they can be quick to reject those they perceive as different. How does this contradiction arise? And how can we help children develop a sense of morality and justice?

“One time—this was, like, a long time ago—I was new in this school, but these people at the school used to judge me because of my skin color and used to disclude me and make fun of me,” Alex, a student of about 10, said to classmates as part of a study my colleagues and I conducted. (Students’ names have been changed for confidentiality.) “I wanted to be their friend. I kind of just, like, ignored them, but they still found a way to get to me. So, like, every single day I went crying to my mom and told her what happened. She just told me to ignore them, but that didn’t help, and it just, like, escalated to the point where I had to see a counselor and stuff.”

For many children, discrimination inflicts anxiety and misery and interferes with their learning. Schools could be far more welcoming than most now are, and I and other developmental psychologists have an idea of how to help them get there.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

After decades of investigating children’s moral development, my colleagues and I have come to understand the reasoning children use to deal with the dissonance between their desire to be fair and their need to belong to friend groups. And we’ve figured out how to help them think through and share their views, particularly about what makes social exclusion unfair and why it’s necessary to stand up against stereotypes and biases.

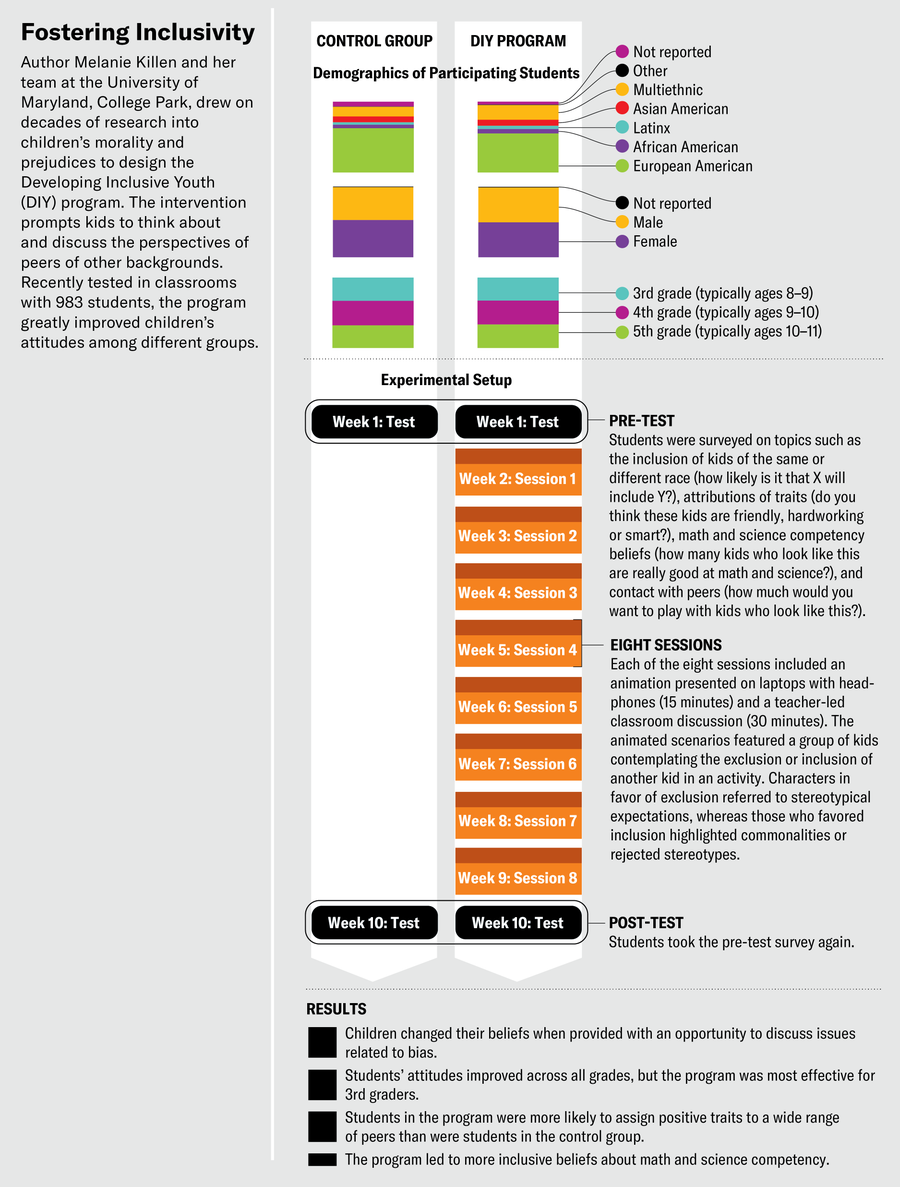

We recently tested our intervention in a randomized, controlled trial, the gold standard for evaluating medical and social treatments, in a Maryland school district. The program significantly improved children’s ability to place themselves in one another’s shoes; enhanced their reasoning in moral conflicts; and helped to foster friendships across boundaries of ethnicity, class and gender. The intervention facilitated Alex’s sharing, after which another student related their experience of exclusion. Responding with empathy and support, the class talked about how to resolve such situations.

Such training and discussions not only help to reduce children’s prejudices but also burnish their ability to resolve conflicts and make school less stressful. Most important, they have the potential to make future societies more just and caring. As kids grow into adults, their ideas of “us versus them” too often harden into prejudices—and that has consequences. If George believes as an elementary school student that boys are better than girls at science, it could influence whom he invites to join the science club in middle school, as well as what he thinks as an adult about whether women can be good doctors, scientists or pilots. Our program shows kids how to challenge such stereotypes with the hope of making society better for everyone.

How do people acquire a sense of justice, and how early does it emerge? Pioneering Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget observed children’s play in search of answers to such questions. He wanted to understand how they develop precepts such as “do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” formalized by philosopher Immanuel Kant as the “categorical imperative.” In his 1932 book, The Moral Judgment of the Child, Piaget reported that even to children, intentions matter: one kid might injure another, but if it was an accident, no one was at fault. To kids, treating others with equality and respect is a matter of justice.

This robust foundation led to studies in multiple countries on how moral thinking emerges. Developmental scientists now know that it starts early: babies as young as eight months old who witness one puppet trying to climb a hill while other puppets either help or get in the way prefer the helpers to the hinderers. Such preferences, based on early forms of empathy, are not yet explicit moral judgments; those show up a couple of years later. By age three, children understand that hurting others is wrong. By age five, they start to share candy equally. Even some animals have a sense of what is wrong, as ethologist Frans de Waal of Emory University and others have demonstrated. In an experiment de Waal conducted with Sarah F. Brosnan, now at Georgia State University, a capuchin monkey became furious when she got a piece of cucumber as a reward for handing the experimenter a rock while another monkey instead got a real treat: a grape.

Children, like capuchins, are social beings, but human morality is exceedingly complicated and requires time to fully develop. As kids grow, family, friends, and others can help them understand why fairness and justice matter. My own lifelong interest in social justice may have something to do with my mother, who was active in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, and my grandfather, who was a leader for workers’ rights in San Francisco during the early 1950s. Growing up in Berkeley, Calif., I attended schools with almost equal proportions of Black, white and Asian students. When I went to college in Worcester, Mass., to study child psychology and moral development, I was surprised to discover that friend groups and dating circles were often segregated by race and ethnicity. I now think these influences contributed to my desire to understand how morality might win out over prejudice.

As an undergraduate, I worked with developmental psychologist William Damon, then at Clark University, on one of his studies of how fairly children divide up resources. In these experiments, chocolate bars were given to students as a reward for making bracelets. Young children often gave more bars to kids of their own gender and age, but by nine or 10 years old they either divided them up equally or gave more to those who had made more bracelets.

During my graduate studies at the University of California, Berkeley, I learned that adults make decisions about morality in the context of group conventions and cultural rituals. Curious about how children would react when rules and norms conflicted with morality, I worked with my thesis adviser, developmental psychologist Elliot Turiel, to offer children hypothetical scenarios and ask questions. If a team captain has to fetch a runaway ball for their team to stay in a tournament, should they do it even if it means ignoring the fact that a little kid is being bullied nearby? Younger children focused on getting the ball, but nine- or 10-year-olds were more willing to violate a convention—the obligation to take care of the team by retrieving the ball—to help the bullied child. As one student said, “Someone could get hurt, and even though you don’t win anything, it’s still good to see that human beings don’t fight.”

These studies made me wonder what happens when a kid’s friends are doing something wrong—rejecting or harassing another kid because of their ethnicity, for example. At the time, very few researchers were studying prejudice in childhood. Social psychologists began studying prejudice in the 1950s because of the dire need to understand how the Holocaust happened. In his book The Nature of Prejudice (Addison-Wesley, 1954), psychologist Gordon W. Allport argues against the idea of an “evil” leader being singularly responsible for that horror, instead focusing on how most Germans had clustered around a shared national identity to the exclusion of Jews, Communists, and others whom they perceived as different and threatening.

It was group dynamics rather than individual psychology that held the key to understanding prejudice, Allport postulated. He elucidated the mechanisms that fostered and maintained group loyalty (such as propaganda campaigns) and pointed out that intergroup contact based on common goals, cooperation, equal status and the support of authorities could reduce prejudice.

Jen Christiansen; Source: “Testing the Effectiveness of the Developing Inclusive Youth Program: A Multisite Randomized Control Trial,” by Melanie Killen et al., in Child Development, Vol. 93, No. 3; May/June 2022 (reference)

But how do prejudices emerge in the first place? After moving to the University of Maryland in 1994 as a professor of human development, I teamed up with Charles Stangor, a member of the school’s psychology department, to study how groups of kids acted when race and gender came into play. Children didn’t always apply their ideas of fairness, we found, when they conflicted with the kids’ group identity. For example, they thought it was wrong to exclude a boy from a ballet club but also said the other kids “would think that John is strange if he takes ballet.” Kids rarely referred to stereotypes when responding to situations of exclusion involving race, however. Clearly, we had to investigate gender- and race-based exclusion differently.

In the early 2000s Martin D. Ruck of the City University of New York, David S. Crystal of Georgetown University and I learned that compared with teenagers who attended homogeneous schools, those who went to more racially diverse schools and had friends of other races and ethnicities were more likely to see race-based exclusion, such as having friends or dates only of the same race, as unfair.

These investigations showed that children identify with groups as early as preschool. These alliances provide social support, camaraderie and protection from bullies. But what happens when being a member of one group means going along with unfair treatment of someone from an out-group? With Adam Rutland of the University of Exeter and Dominic Abrams of the University of Kent, both in England, and my then graduate students Kelly Lynn Mulvey, now at North Carolina State University, and Aline Hitti, now at the University of San Francisco, I started studying how children navigate conflicts between their group affiliations and their sense of justice. When did children and adolescents recognize that their group might be doing something unfair? Would they tell their group that it was wrong, or would they just go along with it?

We showed children of diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds attending Maryland public schools picture cards and asked, for example, whether they thought it was all right for a kid in the picture (named, say, Jordan) to speak up if their after-school club was distributing money unfairly between itself and another club at school. Children between eight and 10 years old were more likely to think that Jordan would tell their friends they were doing something unfair and that those friends would then agree to do the right thing. More important, older children, aged 12 to 14 years, said it was okay for Jordan to tell their friends they were doing wrong, but the group would be unhappy and would probably exclude them. In other words, as they grew older, children came to recognize the cost of arguing against a group norm—a significant obstacle to challenging injustice.

So, for instance, a kid who wants to intervene when their group is teasing a friend of another religion or ethnicity might hesitate to act because they anticipate being kicked out. Further, if they did get rejected, they could be viewed as an outcast by others, adding to the penalty for challenging the norm. Offering hope, however, some kids were skilled at thinking about how to persuade their group to change for the better.

These studies made us wonder whether children would also favor their own group when sharing resources. In one study, led by my then graduate student Laura Elenbaas, now at Purdue University, we asked children whether it was okay that a school attended by Black students got fewer school supplies than a school attended by white students (and vice versa). We also gave them books and other supplies and asked them to divide the items between the schools.

All the kids thought it unfair for one school to get less. But when it came to actually distributing the supplies, younger children had an “in-group bias.” Five- to six-year-olds gave more to the schools that had less to begin with, but they were more likely to give when the disadvantaged school was attended by kids of their own race. In contrast, when giving to schools that had less to begin with, the 10- to 11-year-olds gave more supplies to the schools with Black students than to the schools with white students because, as one kid said, “I’ve often seen that they have less when others have more.”

Surprisingly, there were no differences based on race and ethnicity of the children when it came to giving more to Black schools. A parallel study with my former graduate student Michael Rizzo, currently at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, similarly revealed that a kid’s gender made no difference in how they allocated stickers: they gave more to boys (not girls) who made “blue monster trucks” and to girls (not boys) who made “pink princess dolls.” But as they got older, they allocated more equally.

Regardless of race and gender, kids struggled to prioritize what was right and just over their prejudices and in-groups. The good news was that as children matured, they moved toward what was fair.

Putting together the lessons garnered over decades of research, our team developed what we referred to as the social reasoning developmental model of how children weigh fairness in the context of group dynamics. Morality is more than recognizing that treating someone differently because of their skin color, gender or religion is unfair, we postulated. It requires understanding that systemic biases create disadvantages for certain groups and recognizing when it is necessary to level the playing field.

Using this model, we formulated a set of further questions to understand how to help children become resisters of injustice, or “agents of change.” What factors enabled them to reject unfair treatment of others? And because each child belongs to multiple groups, what happens when these identities come into conflict? It’s not only race and ethnicity but also wealth that confers status, for instance. Which matters more when it comes to exclusion? To answer this question, Amanda R. Burkholder, now at Furman University in South Carolina, and I asked children aged eight to 14 to pick a new member of their club. Children predicted that their peers would pick someone of similar wealth even if they were of a different race, indicating that economic class was a better predictor of common interest than race.

By 2015 we felt we knew enough about children’s moral development to design a program to reduce bias and prejudice, promote friendships across social boundaries and help kids stand up to the unfair treatment of others. Above all, we wanted a program that dealt with children’s own experiences rather than the hypothetical scenarios we’d used in our basic research.

Our intervention program, called Developing Inclusive Youth, offers scenarios involving a morally complex situation and gives children a chance to think through their response and then discuss it with their classmates. After initial testing, we coupled this program with training for elementary school teachers on creating a safe space for classroom discussions so children could think and speak for themselves without being pushed toward any particular ideas.

During the program, elementary school kids between eight and 11 years of age gather in a classroom once a week for eight weeks. Each week they interact with an animated online tool to reflect on and discuss a different type of inclusion or exclusion based on gender, race (Black or white), ethnicity (Asian, Arabic or Latinx), immigrant status or wealth status.

First they get a laptop, put on headphones, then watch 15 minutes of a vignette. As an example, the program might present a situation in which a girl wants to work on a science project with a group of boys. One boy says girls aren’t good at science. Another challenges this notion, saying his sister is good at science. What should they do? After the students watching the program have privately entered their responses, the teacher leads them in a 30-minute discussion while they sit in a circle in the classroom.

During one such session on science and gender, a student shared this story: “I think it was at the University of Maryland summer camp ... we were all inside the dining hall eating dinner, and we saw some older kids do arm wrestles. So [one girl] went up to them and was like—she went up to a boy and was like, ‘Hey, do you want to arm wrestle?’ And then he’s like, ‘You’re a girl; you can’t beat me.’ She ended up crushing him!”

The class yelled in glee, asking how many seconds it took. Then another student offered, “Yeah, at my dad’s work, they’re getting the boys the best jobs and the girls the worst jobs” with less money, after which a third student said, “That’s really unfair!”

The randomized, controlled trial showed that children who went through this program were more likely to view exclusion as wrong; think of children of other groups as nice, hardworking and smart; and have higher expectations about the math and science abilities of children outside their race, ethnicity or gender. Further, they were more eager to play with kids who were different from them and reported fewer social rejections. Many teachers told us they learned new things about their students and became closer to them; the class bonded together more, and, most encouragingly, the students applied what they learned to new contexts, such as when the class read a news article.

Implemented widely, this program has the potential to better equip future generations to stand up to injustice. As one student put it, “No matter who you are, you’re just—you’re part of the civilization. You’re part of humanity. You’re not, like, an alien from another planet.”