The Alluring Mystique of Candy Darling

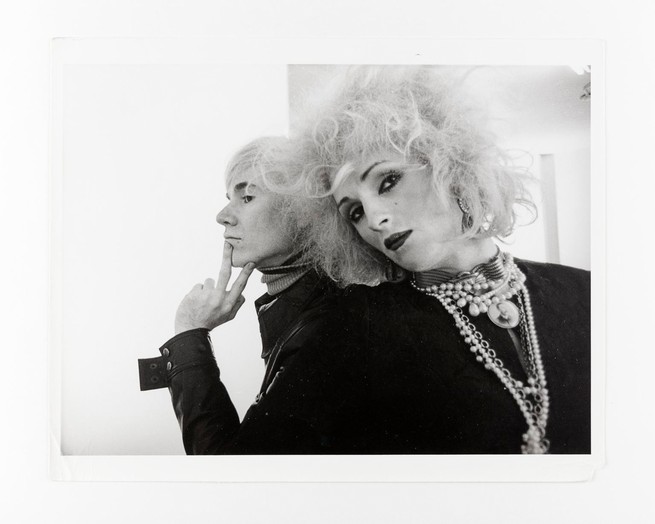

The Warhol superstar was inscrutable in life—and years after her death, her work continues to draw in new admirers.

About midway through the movie Klute, as Jane Fonda, playing a young woman named Bree Daniels, mazes through a sweat-soaked club, the actor Candy Darling appears in the crowd. Pink-lemonade sunglasses frame Darling’s face; her blond locks are held by a patterned bandanna. Bree, floating in a druggy haze, is surrounded by sweaty men with comb-overs. As she steps onto the dance floor, she seems relieved to spot Darling, who’s one of the few women in sight. The two embrace each other as if they’re long-lost sisters before Bree fades into the sea of partygoers. Darling disappears from view; she is only seen, not heard.

Darling’s cameo, which lasted for less than a minute, was one of her few brushes with Hollywood—a world she was desperate to enter. With performances in cult films such as Flesh and Women in Revolt, Darling had become one of the more visible stars to emerge from Andy Warhol’s creative scene, a rarefied clique of experimentally inclined artists, actors, and musicians who left a considerable impression on mainstream culture. But despite flirting with name recognition, she rarely got the chance to escape the realm of the counterculture. When she died of lymphoma at 29, in 1974, Darling still harbored dreams of making it big. It wasn’t enough that Oscar-nominated actors such as Susan Tyrrell, Lily Tomlin, and Sylvia Miles were her fans or friends. She wanted to be one of them, as the author Cynthia Carr makes clear in her prismatic new biography, Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar.

Carr’s book, which is the first biography of Darling, signals a new era for the star’s posthumous fame. Darling, long beloved in queer and trans circles, has been the subject of prior resuscitative efforts such as the filmmaker James Rasin’s 2010 documentary, Beautiful Darling. But between the biography and a planned biopic, a fresh renaissance for her life and art seems to be nearing.

That Darling continues to inspire such fervent devotion isn’t surprising. The miracle of her career is that, despite the hostilities toward trans people in her lifetime—during which members of the community faced nasty prejudice that sometimes metastasized into violence—she produced work of lasting import. Because Darling died young, the scent of unfulfilled promise surrounds her reputation. Carr pieces together Darling’s life from diary entries and a chorus of what she calls “unreliable narrators” who crossed Darling’s path; many times, her research yields no easy answers for what motivated the actor. The portrait of Darling that materializes is one of a woman who was inscrutable even when she lived—a resistance to being read that’s rare in modern celebrity, which might explain her abiding appeal.

The mystique that makes Darling such a compelling biographical subject is mirrored in her screen work. Darling’s breathy, dreamlike line readings may seem like a put-on, but her oblique approach doubled as its own form of emotional honesty: The way she delivered dialogue was often edged with a touch of melancholia suggesting a complex inner life, whether she was playing a wealth-obsessed socialite or some other variation of her off-screen persona. Darling’s cinematic presence was reminiscent of studio-era actors such as Jayne Mansfield and Marilyn Monroe, and in her most piercing performances, she—like the Old Hollywood actors she sought to emulate—had a fearless ability to tap into the reserves of pain from her life. Beneath that carefully constructed mask of composure was a truth—the same truth she lived when the cameras stopped rolling. “You must always be yourself,” Darling wrote in the 1960s, “no matter what the price.”

Born in 1944 to a lower-middle-class family in Queens, Candy Darling spent most of her childhood on Long Island. Her father was verbally and physically abusive, and she was bullied mercilessly at school (“the snake pit,” as she called it). “I was a recluse at seven,” Darling would write of this period. She found refuge in the fantasies of Hollywood—fixating, in particular, on the lavender-blond Kim Novak and her alchemic mix of vulnerability and strength. Novak was groomed to be a palatable starlet in films such as Joshua Logan’s Picnic, where she played a Kansas-bred beauty navigating life in a small town. But the performances she gave in subsequent movies such as George Sidney’s Jeanne Eagels and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, where she convincingly played doomed heroines fighting their fate, expanded her emotional range. Darling worshipped her.

Dropping out of high school at 17, Darling began forging her path away from the hamlet of Massapequa, which she felt was a spiritual prison, toward the relative haven of Manhattan—a place where she could comfortably reinvent herself. In queer hangouts such as Washington Square Park, away from the eyes of her family, she started to transition. Christening herself Candy Darling, she wore sundresses and paisley kerchiefs, and started taking hormonal shots and pills. (She never received gender-affirming surgery—the procedure wouldn’t be offered by an American hospital until 1966.) Making ends meet through sex work, she cultivated an air of glamour by claiming that she was a distant cousin of Novak’s, and referring to her mom’s Massapequa house as her “country home.”

This was a period, Carr reminds the reader, before deadnaming, transgender, nonbinary, and misgendering entered the cultural vernacular. Homosexuality and cross-dressing were illegal. Terms such as transsexual and transvestite were deployed interchangeably; the word queer was still a slur, not yet reclaimed by an empowered younger generation. Darling’s “very existence was radical,” Carr notes, given the climate of bigotry surrounding her, even in comparatively welcoming spaces such as New York City. Not everyone who came across Darling immediately knew she was trans: As a sex worker, she’d sometimes claim to be on her period to avoid detection, and reportedly stopped working as a file clerk at an investment firm because she was “terrified” of people finding out that she hadn’t been born a biological woman.

As the Vietnam War began, Darling made her way into off-Broadway productions and quickly fell in with an avant-garde crowd commandeered by Warhol. His frequent collaborator, the director Paul Morrissey, cast her in Flesh, a film that Warhol was producing about a male hustler. Wearing a shock of poppy-red lipstick, Darling made her screen debut playing herself in a one-scene role. “I think things that move are beautiful,” she says to another woman while frowning after looking at her own appearance, her delicate cadences conveying an unsated longing. “Like your bust. It moves.”

Even though Darling had a minor role, this film effectively announced her as part of Warhol’s entourage; she now had easy entry into the back room of Max’s Kansas City, a favored bar and restaurant for the artist and his social set. But despite the social currency that came with the association—she also began posing for Richard Avedon in the pages of Vogue, and was enshrined in songs by the Rolling Stones and the Velvet Underground—Darling continually struggled to pay her bills and maintain a stable address. Still, her dreams got bigger. Darling lobbied for the lead in a screen adaptation of Gore Vidal’s raucous Myra Breckinridge, a novel about a trans woman who, like Darling herself, is obsessed with fashioning herself into an Old Hollywood actor. Instead, studio suits went with the bombshell Raquel Welch, and losing out on the role would remain one of Darling’s great heartbreaks.

This was an era in which a woman like Barbra Streisand, simply by virtue of her prominent nose, was considered a disruption to conventional female movie stardom typified by the likes of Goldie Hawn and Ali MacGraw. The box office, meanwhile, was dominated by machismo—recall the popularity of very fine films from the early ’70s such as The French Connection and The Godfather. Hollywood was not quite ready to welcome a trans actor into the fold. Acclaimed narratives about homosexuality such as Midnight Cowboy and The Boys in the Band were aberrations in an industry still sloughing off the censorious injunctions of the Hays Code, which had, since its inception in 1934, outlawed “sex perversion” (a byword for a number of perceived moral transgressions, queerness chief among them) in films and was abolished only in 1968.

Darling got a finer opportunity to harness her hypnotic screen presence in the Warhol-produced Paul Morrissey film Women in Revolt, playing a Long Island socialite who yearns for big-screen glory—a biographical extension of the actor herself. Darling, in a delicious early scene, tries to resist entreaties to join the developing women’s-rights movement. “Yes, I want to see everybody liberated,” she sighs, elongating each syllable. “Yes, I want to see everybody happy and free.” Coming from her mouth, these lines register as verbal eye rolls. During the film’s denouement, a New York Times reporter lobs accusations at her, saying she’s just slept her way to the top. Ferocious in her self-defense, she lunges at him. “How humiliating!” she wails. “I’m a big star!” Her hurt is theatrically volcanic but never false.

This haunting performance seemed to emanate from a place deep within Darling, who, like the character she played, moved through public life while concealing her unresolved heartache. “So many times in life, one must put on an act,” Darling once wrote, in a diary entry quoted by Carr. “There are so many situations where the true feelings must be covered by a more acceptable one.” This passage might double as a statement of intent regarding her craft, or at least explain her approach to acting. Darling excelled in playing characters who were big dreamers—and whose retreat into fantasy was, like her own, a form of self-preservation.

Even if the Warhol clan may have been too insular to contain Darling’s ambitions, Warhol’s movies partially functioned as a guardrail against a more caustic mainstream film culture. In Flesh and Women in Revolt, Warhol and his artistic associates cast Darling as a woman, a courtesy other filmmakers didn’t always extend to her. One film Darling made outside of Warhol’s purview, 1971’s Some of My Best Friends Are …, turned out to be an awful experience. The role was a drag queen who is violently assaulted by a man who feels duped by her seeming ruse of femininity, calling her a “little stinky fruit.” Darling’s subsequent on-screen breakdown felt so real that she seemed to be gutting her traumas open for the camera. Carr writes that Darling hated making the film, so intense was her identification with the character’s plight.

That two of Darling’s most wrenching, resonant performances—Women in Revolt and Best Friends—are predicated on verbal and physical male violence against her may make viewers today wince. Yet both films illuminate one of the animating tensions of her life. Darling existed in a perennially uneasy limbo: She could pass for a cisgender woman to the casual eye, a privilege that other trans women did not possess. But she was also subject to discrimination from those who could clock her. One unnamed old-guard actor reportedly refused equal billing with her in a slated 1973 Broadway production of the play The Women; men stopped dating her when they learned about the circumstances of her birth. The theatrical director Ron Link was once so angry about her pulling out of a 1968 production of the play Glamour, Glory, and Gold—she was dissatisfied with the puny size of her name on the poster—that he put up stickers around Greenwich Village featuring her deadname (the name she was born with).

In Darling’s later years, her artistic partnership with Warhol dissolved, partially because of his tendency to discard talent when he felt they’d lost their luster; this contributed to Darling’s own feeling that she was “washed up,” as Carr puts it. Tennessee Williams threw her a life raft when he cast her in his 1972 off-Broadway play, Small Craft Warnings, but Darling could see that her grander ambitions would go unrealized. When her cancer diagnosis came, in 1973, Darling resigned herself to dying young like her tragic blond idols.

Watching these movies a full 50 years after her passing, what sticks out is Darling’s performance style, which was so directly and knowingly referential to Old Hollywood’s studio stars. The outsize theatrics of those women was their way of achieving a more emotive truth, though popular American film, as it turned further toward realism in the 1970s, had little room for such work. The ’70s were a time that the critic Molly Haskell, in her seminal 1974 polemic, From Reverence to Rape, called a cinematic era of “virility and violence”; mainstream movies were so barren of substantive women’s roles that actors such as Ellen Burstyn even threatened to boycott the Academy Awards.

It was as if Darling was working to maintain a link to a form of expression that was becoming an endangered species. And the fact that she fought so openly to carve out a place for herself in such a fallow, harsh landscape—and to be seen as the equal of her other female peers—only makes her work more admirable. She was in search of a future few thought possible for a trans woman like her, even if she couldn’t see the fruits of those dreams in her lifetime.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.