These oft-bypassed towns have all been, at some period in history, influential if not necessarily powerful; wealth-creating though hardly opulent; and vital to the nation’s wealth and security while never fully rewarded for it. Communications and trade once gave some urban centres the edge over others. Churches and marketplaces were social magnets. Today a brand-name art gallery, celebrity residents, or media chatter are most likely to generate appeal, however specious. What if estate agents sold houses using poetry, memories, polyglotism, ruins and rust?

Crewe

“I’ve decided British people all have faces like baked potatoes, or scones, or plasticine modelled by someone who lost interest halfway through. I have a face like that. And so does everybody on this station.” So said Victoria Wood opening her 1996 episode of the BBC’s Great Railway Journeys. Lyrically, it’s subtitled “Crewe to Crewe”. For the rest of us, “Change at Crewe” is more familiar. When I was a regular user of the West Coast Main Line, my trains from Warrington Bank Quay to London Euston stopped at Crewe. I thought of it as the end of the north-west or even the north. The announcement as the train shuddered to a stop was an inventory of alternative lives: Derby, Nottingham, Stoke, Chester and north Wales, Cardiff, Wolverhampton, Shrewsbury, Wrexham, Edinburgh. And back to Warrington. I studied the faces of those alighting to board shorter, folksier trains. Some were students, like me. People who changed at Crewe were hippyish, hirsute, kind, wholesome. The corruptible continued to the capital.

I’ve been through Crewe hundreds of times. I’ve been to Crewe once, which is more than most people. Crewe is not a railway town. It is the railway town. In the 18th century, there was a village nearby, now called Crewe Green, which evolved out of the settlement of Creu, mentioned in the Domesday book; the name derives from an Old Welsh word criu, meaning “weir” or “crossing”. It was part of an ancient parish, Barthomley, which gives its name to an unofficial service area at junction 16 of the M6.

The Grand Junction Railway Company opened its Liverpool and Manchester to Birmingham line in 1837 and moved its railway works from Edge Hill in Liverpool to Crewe. An early example of what would become the Crewe-type locomotive, Columbine, came out of the works in 1845; the beautiful, glossy black engine, topped by a brass steam dome, is on display at the Science Museum. The new town grew up around the station and the engineering plant, and the railway bosses owned and controlled everything. They supplied gas and water, owned the worker housing, opened a library and Mechanics Institution, and endowed and erected a church. “A veritable railway colony,” as George Findlay, general manager of the London and North Western Railway, put it. By the 1870s, the town’s population had swelled to 43,000. In April 1931 King George V and Queen Mary came to inspect the new Royal Train. More than 8,000 locomotives would come out of the works.

I can get tearfully lost down the melancholy line of railway history. But the glory, and pretty much the story, ends with the razing of Crewe Works to create space for a supermarket and houses. The 700ft-long red wall was torn down in 2019; a short film about it, This Wall is Crewe, won a History Channel prize. The Crewe Heritage Centre, which occupies the site of the former London, Midland and Scotland railway yard, displays assorted rolling stock, signal boxes, steam-puffing paintings by Harry Watson, model railways, and other rail fan-oriented paraphernalia. Everybody sees one of its most evocative exhibits – a prototype of the Advanced Passenger Train – as they ride through. The project to roll out the pioneering tilting high-speed train was dropped when the government of pro-car Margaret Thatcher withheld funds.

The railway company’s monopoly was broken in 1938 when the Crewe Corporation Act was passed. In the same year the potato fields of Merrill’s farm were chosen for the construction of a shadow factory – removed from the Luftwaffe-luring ports and cities – to manufacture Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. After the war, car production began, turning out dream machines like Bentley Mark VI’s and Rolls-Royce Silver Dawns. For some reason, in Crewe motors of the latter marque were always Royces, never Rollers. Today the Bentayga and Continental GT are made in Germany but assembled and painted in Crewe. Crewe is also the UK and perhaps global centre of ice-cream van production. New e-vans sell for £142,245. John Cooper Clarke tells a joke about a man who wants a Silver Cloud and ends up with a hula-hoop. I like the idea that one of Alderley Edge’s footballers messes up his online order form and ends up driving not a royal blue Bentley but a pink and white Mondial Lusso van, kitted out with a Rapida X soft ice-cream machine.

I hate cars. I love trains. In December 2021, the vestigial Crewe Works – part of Alstom – signed a deal to co-produce 54 trains for HS2. In October 2023 Rishi Sunak scrapped the line from Birmingham to Crewe and Manchester; the money is being used to fill potholes. Labour has not publicly confirmed nor denied plans to build at least the section to Crewe. Will this “northern powerhouse” end up being, all over again, merely the workshop for a southern powergrab?

Things to see: Crewe Hall, Bertoline’s Church and White Lion Inn in Barthomley, Crewe and Nantwich Circular Walk.

Stirling

There’s always a degree of jeopardy when tourist boards denominate a place a “gateway” to somewhere else. But Stirling, at least, has the castle atop a precipitous volcanic plug to bellow its substantial claims for attention to those who would otherwise speed onward and upward. From April 2024 to April 2025 Stirling celebrates its 900th birthday as a Royal burgh, which was King David I’s way of endowing Scotland’s scattered and unstable settlements with political representation and legal status, while encouraging foreign trade and local markets along continental lines – and getting his hands on tax revenues. After the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, Stirling shared the rank and privileges of a capital city with Edinburgh; Stuart kings routinely switched residence between them. At the Union of the Crowns, James I/VI moved to England and London took over. If history – laced with myth and legend – is your thing, you have definitely arrived when you come to this gateway.

The Back Walk at the base of the castle is a circular footpath following the old city walls that was built in the 18th century and paid for by William Edmonstone of Cumbuswallace, a scion of an ancient clan. Where the path frees itself from tree cover, there are views across the surrounding Lowlands, up to the Highlands and over the floodplains and rich agricultural land, known as the Carse of Stirling. Along the way, there’s a wooden statue of a wolf – alluding to a local, internationally reiterated, fable about invaders fleeing howling canids – and, on the Mote Hill, a well-used beheading stone covered by a metal cage – presumably to stop anyone stealing it (or using it). Some sources allege it was being employed as a butcher’s block in Bridgehaugh until the Stirling Natural History and Archaeological Society came to the rescue.

You can see the Wallace monument from the Back Walk. You can probably see it from space. In 1997, a 13ft, 12-tonne gold sandstone statue of Mel Gibson as William Wallace made by stonemason Tom Church was erected in the car park. The actor’s face was ostensibly depicted as shouting (“Hold! Hold!” ) but looked as if he was yawning. It was universally loathed, frequently vandalised, and it, too, had to be caged. It was given back to Church, who gifted it to his local football club, Brechin City.

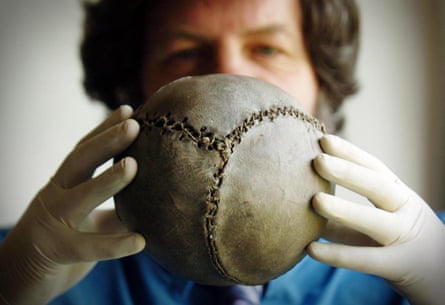

The world’s oldest football was discovered during an excavation project at Stirling Castle in the 1970s; it had been lodged in the rafters of the Queen’s Chamber in Stirling Castle during the reconstruction works commissioned by James V, which dates the hoofing of it to the 1540s. The ball, made from cowhide and a pig’s bladder, is prominently displayed at the Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum. Football was played by some Scottish monarchs and disdained by others as corrupting and sinful. A short Middle Scots poem lists the disadvantages: snapped bones, shredded ligaments, crippling injuries:

The Bewties of the Fute-ball

Brissit brawnis and brokin banis,

Stride, discord and waistie wanis.

Crukit in eild syne halt withal,

Thir are the bewties of the fute-ball.

Things to see: Stirling Central Library, Flanders Moss national nature reserve, Stirling Old Town Jail

Boston

I have a soft spot in my secular soul for St Botolph, after whom Boston is named. When I was a theology student in the mid-1980s, I had a summer job as verger of St Botolph’s without Aldersgate in the City of London. Botolph is the patron saint of boundaries and travel. Three other churches dedicated to him once stood guard at London’s gates.

His greatest house is in Boston, where his church, completed in the 16th century, is known as the Stump – despite being one of the tallest in the country. The lantern tower’s shadow is black and infinite at sunset, but light floods the inside. First Edward VI and then Puritans replaced the original stained glass with clear to let in the “cleanly” light of the Gospel. The tinted glass we see today is Victorian. Though its foundations lie in clay below the water table, often inundated by river and sea, the church is still almost perfectly perpendicular. It’s a vaulting, expansive palace of arches, castellations, friezes and tracery, a Gothic hulk in the least “gothick” of landscapes.

Some people balk at the flatness of the Fenlands. I find them soothing – no need to pant and gasp to get around this kind of landscape – and the dome of sky above liberating. Poet Paul Verlaine travelled to England after being released from prison – he had been sent down for shooting his lover Arthur Rimbaud – and found himself at Stickney teaching French and drawing. He moved to Boston in search of more affluent pupils, where he lodged with an Italian photographer who had a sideline – a museum of curiosities that included a whale skeleton. According to the poet’s biographer, Bechhofer Roberts, the two bohemian expats “emulated Jonah by placing a table and chairs inside the whale’s belly and spending their leisure hours there over a glass of beer and a pipe”. When not out walking with his pupils, Verlaine worked on his poems. He missed Rimbaud desperately and wrote his last ever letter to him while in Stickney. Sagesse (1880/81) contains this verse about the Fens.

Rows of hedges

Roll to infinity, sea

Clear in the clear mist

Which smells good, like young berries.

Debussy used the lines in one of his 3 Mélodies de Verlaine.

Old Boston looked east for trade. The Hanseatic League, which dominated the North Sea and Baltic, had a depot here. In the 13th century, the port of Boston was said to be the second most important after London. Sheep fleeces, lead and salt were shipped to Europe. In came wine, pelts, spices and silk to be sold at the market. The earliest maps of Boston show the Market Place – one of the country’s largest – at its current location. Once a year the London courts would close so that the monied could visit Boston for the May Fair.

The Fens suggest an extension of the Low Countries, as if Doggerland slipped underwater just last week. The surrounding area is known as Parts of Holland. Tulips are grown. The long-serving dykes, ditches and pumps, and even the modern Boston tidal barrier, would be familiar to a Netherlander. The Flemish bond on the high street, the curved gable at Church House on Wormgate and the stepped frontage above 10 South Street feel foreign, but not very. The outdoor sequences for the 1942 war film One of Our Aircraft is Missing, set in Nazi-occupied Holland, were shot around Boston.

But many Bostonians went west, joining the outflow of unhappy Christians who followed St Botolph’s minister John Cotton and the pilgrims’ spiritual leader William Brewster (who was imprisoned in the Guildhall in 1607) to New England. A twelfth of Boston’s population would end up in Massachusetts. Architectural notions accompanied them. Yale University’s Harkness Tower was inspired by the Boston Stump. So is New York’s Riverside Church. Some skyscrapers quote it.

In a distant time when Europeans wanted to live in the UK (2010-2015), Boston attracted the largest contingent of Lithuanians and second highest number of Polish immigrants in the country. Latvians and Romanians also made up sizeable communities and a tenth of the town was “Eastern European”. Ukip targeted the seat, without success, and the right-wing press referred to “Little Poland” and “Boston Lincolngrad”. Some 65 languages were spoken in a town of 70,000 people. Only a microscopic brain desiccated by parochialism wouldn’t find that potentially inspiring. Then again: a tower, a doomed flood plain, many tongues. How high is that Stump?

Things to see: We’ll Meet Again museum, RSPB reserves at Frampton Marsh and Freiston Shore, Bubble Car Museum at Langrick

Barnstaple

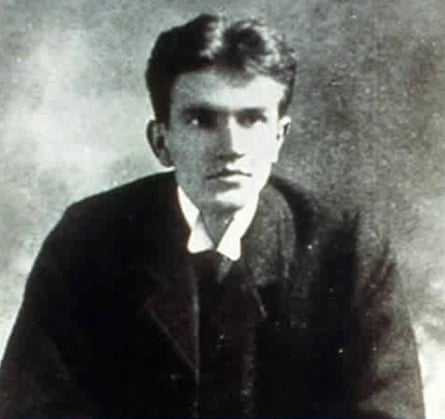

One source says Joy Street, most say Cross Street. Both are, in their way, suitable addresses for WNP Barbellion, the Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, Sartre and Grossmith of Barnstaple – or Downstable as he called it. Born in 1889, Bruce Frederick Cummings – as he was baptised – took a keen interest in natural history, but followed the advice of others and the model of his father, an acerbic Tory columnist, taking up a career in journalism (“my Death Warrant”) via a five-year apprenticeship at the Devon and Exeter Daily Gazette. Later he did manage a stint at the British Museum (Natural History), but illness, his parents’ deaths and a troubled relationship got in the way of any sustained career as a bookish naturalist. The Journal of a Disappointed Man (1919), which he began to keep when he was 13, is a record of dashed dreams, ennui, bouts of sickness, notes for a novel never to be written, assorted vivisections, “mental ebullition”, loathing for Christians and humans in general.

HG Wells provided the introduction to the first edition. Barbellion died seven months after the book was published – to considerable acclaim. He was 30.

Literary pilgrims should be pouring into Barnstaple. Barbellion is as curative as the sea air. Which his town sadly lacks and, given that tourism has fully replaced wool and tin in the West Country, is often bypassed by the surfboard-wielding hordes motoring to Croyde or heading for the wilds of the moors.

Barnstaple had a mint in the 10th century, and a market and annual fair were in operation by 1274. The tax records of 1332 establish Barnstaple as the third most prosperous borough in the county, after Exeter and Sutton Prior (Plymouth). In medieval England, wealth was concentrated along a southern axis that ran from Canterbury to Totnes; Barnstaple was the western extremity. Its wealth was due to shipping and the manufacture of woollen cloth, as well as agriculture and, later, pottery. The town had its own customs house and continued to grow until the mid-18th century. The port silted but the railway came. When I lived in south Devon, I used to watch the slow stopper leave – the sad-looking solitary link to the north of the country. It’s scenic and goes by the family-friendly nickname of the Tarka Line.

If this ancient burh (fortified town – against the Vikings) could write a journal, it would have to confess to some measure of disappointment. Its recent fortunes have traced a sharp parabola. Barbellion writes that he hates the little town (though nowhere really satisfies him), but the gloomy diary entries of Barnstaple’s bard transform the place. Morose existentialists need no longer flee to Copenhagen, Paris or Weimar to walk on the shady side of the street.

Things to see: Pannier Market, Lynton & Barnstaple Railway, Museum of Barnstaple and North Devon