As part of the NHL Green initiative celebrating Green Month in April, NHL.com will feature stories on how the NHL is looking to grow and protect the game of hockey and its communities for generations to come. Today, Robert McLeman from Wilfrid Laurier University and the RinkWatch Project, writes about the future of outdoor rinks. NHL Green and RinkWatch have been working together since 2016 with a common of goal of our protecting our game and planet for future generations.

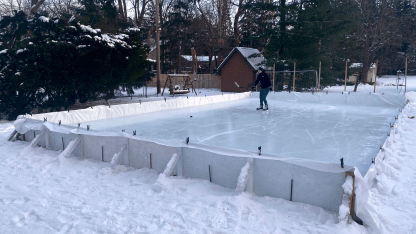

This past winter was challenging for outdoor skating rinks. Cold weather was slow arriving, and temperatures bounced up and down like yo-yo. January saw short periods of intense cold across extending so far south that people in Dallas and Atlanta got in on the ODR action. There were many more mild periods and some rain, but not much snow.

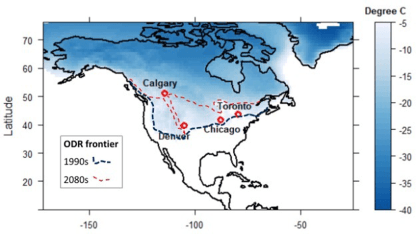

In early February, summer-like temperatures broke records in cities of the NHL's Atlantic and Metropolitan Divisions, and in much of the Central Division as well. Many ODR makers from Chicago eastward decided to break down their boards and get out the golf clubs. Those who hung in were rewarded with a few extra days of skating in mid-to-late March and packed up their rinks about the same time as ODRs on the Canadian Prairies and northern Great Plains, where the ODR season is longer because of the West's generally colder winter climate.