Why Pop Culture Keeps Falling for the “Gay Liar”

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

In Ripley, we are asked a question that goes to the very heart of the gay experience, where envy so often meets desire: Does he want him? Or does he just want to be him?

Andrew Scott stars in the latest adaptation of novelist Patricia Highsmith’s 1955 psychological thriller The Talented Mr. Ripley, last seen onscreen in the 1999 film of the same name starring Matt Damon and Jude Law. The new Netflix limited series, directed and written by Steven Zaillian, feels much darker than its predecessor—and not just because it is gorgeously shot in black-and-white. First, we see a more weathered Tom Ripley than Damon’s, living in a dilapidated New York City apartment and making money via a series of small-time scams. Then, he sneaks his way into the opportunity to travel to Europe in search of Dickie Greenleaf—a wealthy heir living off a trust fund on the Italian coast. Though his mission is to lure Dickie back to the United States, Tom instead becomes entranced by him: his handsome looks, his expensive clothes, his knowledge of the arts, and the privilege that helps him glide through the world as he pleases. Tom wants it all.

The more terrible things Tom does (and he does many), the more his lies keep piling up. Netflix’s fresh take on this story is timely, because our culture in this moment is especially fascinated by liars. Often, their motivations seem clear—money, power, fame—but other times, we’re less sure. Now, a particular subset of fabricator is being welcomed into the content stream: the Gay Liar. From the corridors of Capitol Hill to real-life scammer stories, novels, and prestige TV dramas, cultural representations of gay men are leaning toward figures who lie, betray, and then lie some more.

Despite the long history of queer people being mischaracterized and indeed demonized by the media, I find myself drawn to these villains—and not just because they’re so often dramatic in a distinctly gay way. Their stories, both real and fictional, are complex and tap into decades-old tensions still at the heart of queer life today. In a sea of tepid LGBTQ+ representation, even the most prolific Gay Liars can spark more honest conversations.

On the second and most recent season of The White Lotus, one guest from season one returned to HBO’s cursed resort. Tanya McQuoid—the damaged and delusional millionaire played by Jennifer Coolidge—ended up lured to her death by a British aristocrat named Quentin. Spoiler alert: It turned out “high-end gay” Quentin was secretly broke and plotting to scam Tanya out of her fortune with the help of Jack, a sex worker posing as his nephew. Coolidge’s memeability achieved new heights when, aboard Quentin’s palatial yacht off the Sicilian coast, Tanya finally realized what was going on, and disclosed her plight to the boat’s captain: “These gays, they’re trying to murder me!”

It amused me that, out of all the terrible people on this show, the most deceptive and evil were a group of gay men. (British gay men, specifically—a subset I belong to.) The scene’s similarities to Ripley are obvious: a stunning Italian backdrop, a financial scam and brutal murders, but also the depiction of Gay Liars as well-dressed sophisticates with a certain fabulosity. Watching Scott’s psycho-chic take on Tom Ripley, I was reminded of Andrew Cunanan—the real-life killer whose final victim was Gianni Versace. In the 2018 FX American Crime Story season devoted to the murder, Darren Criss portrays Cunanan as a pathological liar, who used his beauty and charm to his advantage.

Gay Liars, both real and fictional, are often driven by the pursuit of money. Cunanan would invent false aliases and life stories, racking up huge bills on stolen credit cards—a gateway to more serious violent crimes. Watching Ripley, I was struck by how much more subtly Tom’s romantic and sexual obsession with Greenleaf is portrayed compared to the 1999 film. Scott’s version of Tom seems more obviously driven by financial yearning and jealousy—not only of Greenleaf, but also his queer-coded friend Freddie, played by Eliot Sumner. There are clear parallels here with Saltburn, too—Emerald Fennell’s much kinkier British take on class and envy, in which queer villain Oliver Quick enjoys the company (and fluids) of women and men throughout a Ripley-esque rise to the top.

In 2023, disgraced former congressman George Santos became one of the most famous (and shameless) Gay Liars in America. Since being expelled from Congress amid fraud allegations, the list of federal charges against him has grown to 23—a serious docket by anyone’s standards. The accusations include using campaign funds to pay for designer clothes, OnlyFans, and Botox, stealing from the credit cards of donors, and falsifying campaign finance records to secure more funding from the GOP.

New York Times reporters Michael Gold and Grace Ashford aired the inconsistencies in Santos’s claims after pulling together a story on his election win. First, there was a pet charity he said he’d founded, which didn’t check out. Then, neither Goldman Sachs or Citigroup, where he claimed to have worked, had any record of his employment. “That’s when the dominoes started to fall,” Gold tells me. Santos’s backstory quickly unraveled, including most of his employment history and his education, financial status, property ownership, ethnicity, and religion. His most bizarre claims were that his mother had died during the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, and that four of his employees had been murdered in the 2017 shooting at Pulse Nightclub. (Oh, and that his niece was abducted by Chinese communists.)

Looking back at how huge the story became, Gold thinks Santos fits into a wider trend of fraudsters making headlines, including Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes and Fyre Festival organizer Billy MacFarland. “There is an American fascination, I think, with the way that lying can get people into positions of power,” Gold says. “Fraud and scamming were at the center of pop culture—and here comes this congressman, right on time.”

There is a specific gay love for women who scam. I remember my feed being full of posts (semi-ironically) stanning Desperate Housewives actor Felicity Huffman after she was arrested in the 2019 college admissions scandal. (#FreeLynette started trending, and there was even court-themed merch.) The previous year, fake New York heiress Anna Delvey served high fashion courtroom looks. A few months ago, a photograph went viral of Theranos’s Holmes and Real Housewives star and convicted wire fraudster Jen Shah together in the Texas prison where they are both serving jail time, not looks.

Queer academic José Muñoz calls the process of gay men identifying with female icons disidentification. He thinks it could be a “coping mechanism” for our feelings of exclusion from mainstream culture. Traditionally, gay icons are vocal powerhouses like Cher and Patti LuPone, or tragic figures such as Judy Garland and Princess Diana, but there is also a gay love for villains. Fictional scammers like Rosamund Pike in Gone Girl tap into a survivor spirit that is similarly relatable or even inspiring to a gay audience. At a time of greater queer inclusion in the mainstream, stanning real-life criminals comes with an even greater sense of taboo, or being “in on the joke.”

Speaking of survival, I wonder how the closet fits into the Gay Liar archetype. Growing up, I don’t remember a specific moment when I realized I was gay, but I do recall lying about not being gay all the time. In fact, I still remember the very first time I was asked directly and gave a response that I knew, deep down, wasn’t truthful. (Maybe a lie was my moment of realization? Whew.) To be in the closet is to create a “straight” version of yourself, who might have fabricated interests and hobbies specifically designed to throw others off the scent, or even a partner of the opposite gender. The most messed-up part of this is that, while we teach children not to lie from a young age, this specific type of lying is encouraged when our society either promotes heterosexuality as superior or assumes it as the default.

In his 2023 novel Confidence, author Rafael Frumkin explores these ideas through the lens of a queer scammer duo. The book is a queer Robin Hood tale, in which besties (and occasional lovers) Ezra and Orson unite to start a company that promises “instant enlightenment.” Frumkin argues that queer and trans people might be “uniquely well positioned” for scamming, precisely because they are used to “being different people to different people” in a more conscious way. “If you didn’t grow up in an accepting place, you are immediately forced into a kind of chameleon-ism,” he says. “If you’re 12 years old and in the closet, you’ve got to keep your story straight!”

Frumkin thinks this type of “assimilationist instinct” is grounded in self-preservation. In a wider sense, assimilation has been at the heart of intercommunity political disputes since the 1969 Stonewall uprising. Should LGBTQ+ people assimilate within existing systems like capitalism and structures like marriage? Or should we seek to liberate ourselves from them? In this debate, gay scammers could be read as disruptive or even liberationist. By gaming the system, they’re subverting it, surely?

I think the opposite is true. The vast majority of the gay scammers we see in pop culture are American, and in her book Trick Mirror, Jia Tolentino argues that scamming is central to American life. She writes that to be American is to learn that “one of the best bids a person can make for financial safety” is to get “really good at exploiting other people.” She positions scamming as, rather than subversive, “the quintessential American ethos.” Gay scammers merely represent queer inclusion into, or assimilation within, a capitalistic interpretation of the American dream. “Queer people can now join the army and they can get married—and they can fucking con people, too,” Frumkin says. And there is a tension here, between inclusion in the American ethos of individualism, and the supposed collectivism of the LGBTQ+ community. “Gay scammers are sort of saying, well, who gives a fuck about the collective? It’s about me,” he says. “Wanting to be at the top of the pyramid scheme? That’s as American as apple pie.”

Initially, Santos’s historic 2022 election win looked like a sign of a changing America. He became the first-ever Republican to be openly gay before election to federal office. Santos defeated Democrat Robert Zimmerman, another gay man, also making the race likely the first time that “out” gay candidates from the two main parties had faced off. “A gay Brazilian Republican was running for Congress, and eventually won, at a time where the Republican Party was talking a lot about winning over different kinds of voters,” Gold remembers. “It was definitely an interesting story.”

Santos’s transition from corrupt politician to celebrity is the next chapter of his story. Reflecting on Santos’s newfound fame, Gold thinks it was partly driven by how “brazen” his lies were—even against the backdrop of former president Donald Trump, who made over 30,000 false statements while in office—but also the “tech and media ecosystem” he is shrewdly navigating. “When you can set up a Cameo account and make more money than you ever did in Congress,” he says, “that is a pretty unique thing.” Santos alluded to this himself during an interview with Ziwe, who asked: “What can we do to get you to go away?” He replied that people should stop inviting him to things. “But you can’t,” he added, “because people want the content.” Santos does in fact represent a changing America—one where lies are a form of monetized entertainment.

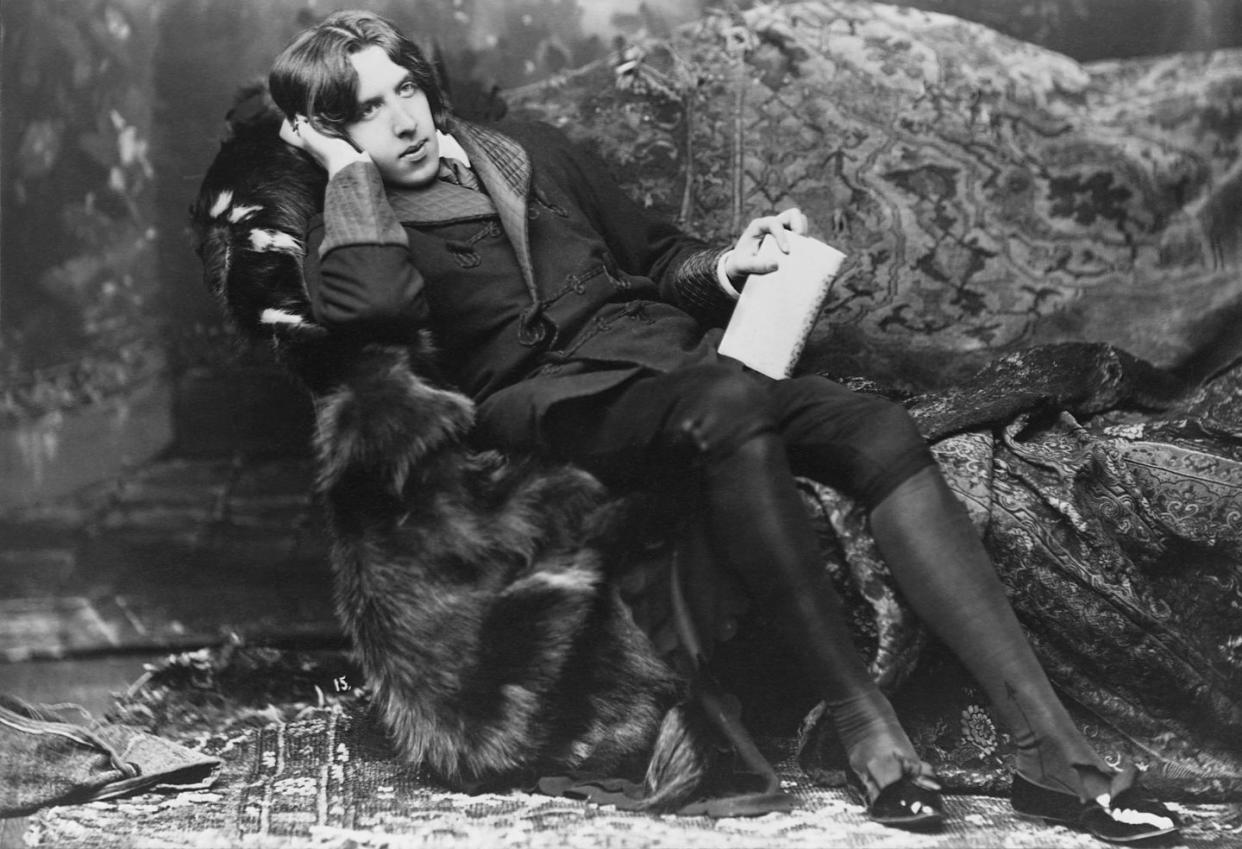

When discussing any trope in queer representation, it’s important to mention that the line between archetype and harmful stereotype has always been fairly thin. Some might interpret representations of Gay Liars and scammers as homophobic—part of the long lineage of queer-coded characters who are also villains. I grew up watching characters like Scar in The Lion King—a curiously British and very flamboyant lion who sends Simba’s father, Mufasa, falling to his death. Devious characters like Oliver in Saltburn, or Francis Underwood in House of Cards—another Machiavellian man who had sex with men, and was known for pushing his enemies in front of moving trains—could be interpreted as perpetuating a harmful link between queer men and danger. This narrative has been reappearing with varying intensity in the media right back to the trial of Oscar Wilde, when the writer’s affair with a British aristocrat sparked a moral panic in 1895 Britain.

I don’t think that is what is happening here currently. Gay Liars having a cultural moment feels more like a response to a wave of queer representation that has frequently produced pedestrian and risk-averse characters. In 2022, historian Ben Miller and novelist Huw Lemmey published Bad Gays: A Homosexual History, a book based on the authors’ podcast of the same name. Both projects approach queer history with a central thesis: If we analyze the past solely from the perspective of queer heroes like Wilde, then we’re getting only half the story. The duo argues that the gay gangsters and evil twinks from queer history—like Lord Alfred Douglas, the young lover who betrayed Wilde—have contributed just as much to what we might recognize today as a cohesive Western gay identity.

Miller thinks that the newfound cultural prominence of “bad gays” comes from a desire among queer audiences, specifically, for a more “grown-up” conversation than #PositiveRepresentation often allows. “Actual queer people are interested in more complex stories that are by, about, and for grown-ups—as opposed to the kind of childish or adolescent narratives that make up a lot of queer representation.” It’s great to have cute TV shows about gay teenagers holding hands in school, queer lifestyle gurus (influencers) giving people makeovers, or Glee kids shrieking their way through “Defying Gravity.” But there is greater inclusivity and value in striking a balance with queer people who are complex and flawed. How does someone go from being a drag queen in Brazil, to advocating against same-sex marriage and speaking at a “Stop the Steal” rally wearing a stolen Burberry scarf? Santos asks us these questions. “We would very much like it to be true that living through repression sanctifies people, or makes them better,” Miller says. “When in fact, it can often make people worse.”

Watching Ripley, I was struck, as I often am watching scammer stories, by how much I ended up rooting for Tom. There is something about his ability to shape-shift that makes him addictive to watch. Reinvention comes up often when discussing Gay Liars. Gold thinks Santos taps into a fascination that we all have with people who use bold lies to “reinvent themselves in massive, huge ways,” while Frumkin says Gay Liars share America’s central premise: “You can constantly remake yourself.” Transforming oneself in pursuit of more, or better, is as close as you can get to a universal gay experience—one that these stories take to the darkest extremes. If Gay Liars tell us one truth, it’s that reinvention is the queerest form of fantasy.

You Might Also Like