- India

- International

Work or vote? It’s a choice no citizen should have to make

Socio-economic causes, practical constraints, and structural barriers deter migrants from participating in the biggest festival of democracy. Their rights need to be protected better

People wait in queues to cast their votes during the Tripura Assembly elections in Agartala. (Express photo by Abhisek Saha)

People wait in queues to cast their votes during the Tripura Assembly elections in Agartala. (Express photo by Abhisek Saha)Every year, millions of internal migrants are pushed out of their homes in search of livelihoods. They gravitate towards urban centres. After migrating, they usually get absorbed and frozen in the interlocking and exploitative urban informal sector, inviting a new array of problems. Consequently, their migration affects the quality of human capital as it does not significantly change their lives. They remain cogs in the machine and are marginalised. Along with vulnerable employment, the disenfranchisement of millions of internal migrants due to their mobility and multi-locational residence further invisibilises them.

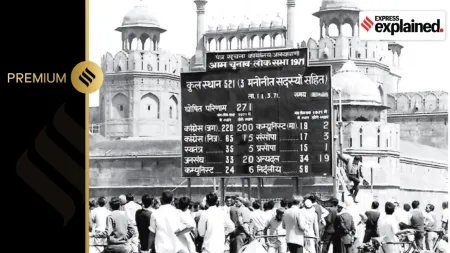

According to the Census (2011), 450 million people (or 37 per cent of the total population of India) are internal migrants. By 2023, their number is likely to have increased by another 150 million. These numbers are enormous and most are short-term and temporary migrant workers. They also indicate that many citizens were deprived of their fundamental right to vote. To ensure social protection, access to justice mechanisms, and to make inclusive democratic practices, the political and civic inclusion of internal migrants is a prerequisite. Unfortunately, in the 2019 general election, nearly 300 million voters were missing, among whom migrant workers constituted a major proportion.

It is essential to understand the socio-economic causes, practical constraints, and structural barriers that exclude migrants from participating in the biggest festival of democracy.

Due to prolonged unemployment after sowing or, according to agricultural off-seasons, most workers migrate seasonally. As their migration is temporary and circular, they prefer not to change their voting constituency to their place of work. Vulnerable employment, low wages, uncertain livelihoods, cheating, and payment delays are baked into the informal sector, where most migrants work. In addition, the Covid pandemic led to catastrophic after-effects on migrants and deepened the inequalities in the informal labour market. Against this background, leaving work and travelling to their hometown to vote becomes unfeasible. Travel expenses constitute a huge additional financial burden, including taking gifts for family members, leave without pay, the possibility of wage loss, and wage theft. Migrants have to choose between voting or working and often, circumstances force them to work.

Long distances remain a crucial stumbling block that keeps inter-state migrants from casting their vote. Labour source states — Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh – are generally less urbanised than destination states of Maharashtra, Delhi, Punjab, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Kerala. Several urban centres in these states have emerged as “growth engines”, pulling interstate migrants from backward regions across the country. In addition, the Smart Cities Mission will also attract migrants to both established and emerging cities.

While many inter-state migrants are rendered disenfranchised, creating a space for proxy voting, local candidates bring short-distance migrants to their hometowns during elections. This can lead to unethical practices and can compromise democratic principles.

To recognise migration-based disenfranchisement and improve voter turnout, the Election Commission of India has introduced Remote Voting Machines (RVMs) to extend voting facilities to migrant workers, which is indeed a crucial step. Several technical, logistical, and institutional challenges exist in implementing the RVM. However, it is possible to overcome these hurdles with political and public will. Many migrants do not have proof of domicile, such as an Aadhaar card and voter IDs. Without essential documents, migrants remain unenumerated and unrecognised at the local, regional, and national levels. It negatively impacts their political inclusion and bargaining capacity. In 2024, many migrants, especially from West Bengal and Assam, are travelling home to cast their vote to ensure their citizenship credentials. This is because of anxieties stemming from the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and National Register of Citizens. Such mobility is distressing and puts a financial burden on these migrants.

Migration symbolises aspiration and freedom. It has the potential to expand people’s capabilities. Many studies have noted migrants’ critical contribution to the country’s GDP and socio-cultural growth. Despite this, their political exclusion raises several concerns about their rights.

With disenfranchisement, internal migrants are disconnected from their native places on the one hand and cannot claim citizenship rights at their destinations either. In some places, the politics of the “son of the soil” triggers hostility towards migrants. It is important, in this context, to see how political parties include internal migrants in their election manifestos. Their votes will empower them and make their problems more visible, resulting in effective policy measures. Specific measures to protect their right to vote and the right to migrate will result in a more inclusive and vibrant democracy.

The writers are Chair and Senior Research Fellow, respectively, at the International Institute of Migration and Development (IIMAD), Kerala, India

EXPRESS OPINION

More Explained

May 01: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05