A dark moment for Connecticut

Editor’s note: This story was drawn mostly from the archives of The Day, the New London Daily Globe and the Westerly Sun, with additional material from many online sources. Click links in the text to see original stories in The Day.

The first sign that something big was happening came a year in advance: Officials from the U.S. Naval Observatory were in New London scouting locations for a giant telescope.

Nothing came of it, but the search heralded an astronomical event rarer than rare. Twelve months later, on Jan. 24, 1925, New London and most of Connecticut saw a total solar eclipse as a crisp winter morning turned to night.

The event was unique in modern times here, though northern Connecticut also had one in 1806. The next one isn’t due for 55 years.

On Monday, Connecticut will experience something slightly more common: a partial eclipse that’s total elsewhere. That last happened in 2017. Weather permitting, it should be a good show but nothing like the experience of 99 years ago.

The 1925 eclipse brought mass movements of people, saw astronomers take to the skies, inspired artists and advertisers, and drove a few people crazy. And thanks to the unpredictability of Mother Nature, it was all almost for naught.

* * *

As anticipation built in January, people looked ahead with a sense of amazement.

“Then will be felt much the same instinctive feelings of wonder and humility and a bit of fear which smote the ancients,” columnist Frederick P. Latimer wrote in The Day.

Astronomers could count themselves doubly fortunate. The eclipse would pass over New York City and Connecticut, a populated stretch full of colleges. That meant no fewer than five observatories were near the center of the totality path, including those at Wesleyan and Yale.

“These will afford to professional astronomers … opportunities which are granted to individuals less than once in a lifetime,” H.C. Wilson wrote in “Popular Astronomy.”

Harvard’s astronomers weren’t so lucky. Totality wouldn’t come to them, so they had to go find it. Teams were dispatched to take photos and measurements in Buffalo, Poughkeepsie, Nantucket and New London. The four locations were a hedge against cloudy skies.

Observers also had new options thanks to the miracle of flight. The most ambitious undertaking involved a craft that had the briefest of heydays. A Navy airship, USS Los Angeles, would carry seven scientists into the totality zone, hopefully providing a stable platform for observation.

Connecticut Gov. John H. Trumbull issued a proclamation that called the eclipse “a scientific event of the first importance” and urged schools to devote time to studying it. Interest was also sparked by public lectures and Sunday sermons.

Thousands wanted to see the show, and that created opportunity for the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, which scheduled “Eclipse Specials.” One train would travel from Wellesley College to New London, two more from Worcester to New London and another from Boston to Westerly. The coast was closest to the center line, where the eclipse would last longest. Locally the line passed just south of Plum Island.

With the shore as ground zero for viewing, there were plenty of last-minute questions. Where would all the incoming people go? What about traffic? What should be done about streetlights?

And most important: What if the weather didn’t cooperate?

* * *

Humans have been predicting eclipses for so long that legend says two Chinese astronomers were beheaded for missing one in 2134 BCE. Rulers saw them as bad omens, like the one that coincided with the death of King Henry I of England. In ancient Greece, the warring Lydians and Medes put down their arms after interpreting an eclipse as a sign of peace.

Eclipses have played a role in the discovery of helium and the confirmation of Einstein’s theory of relativity. In 1806, the brother of Shawnee Chief Tecumseh successfully predicted one, helping to unite several tribes.

For all the hoopla and misunderstanding, the science is straightforward: The moon passes between the Earth and sun, briefly obscuring the sun along a narrow path where its shadow falls. The sun is partly visible in a much wider area.

When the moon is farther from the Earth, its apparent size is smaller, resulting in an “annular” eclipse, in which sunlight forms a bright ring around it.

Eclipses loom large in popular culture, appearing in works of fiction like Mark Twain’s “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court,” films including “Fantasia” and “2001: A Space Odyssey” and TV shows from “Star Trek: Voyager” to “Mad Men.”

* * *

Leon Campbell, a Harvard astronomer, arrived in New London with more work than he could do alone. A reporter from The Day was recruited to help with photography, and Bulkeley School students would assist measuring light and temperature. The team would work from Connecticut College.

At Naval Air Station Lakehurst in New Jersey, the dirigible Los Angeles stayed in its hangar as eclipse day approached. A blizzard had scrapped plans for a dry run, and winds remained high.

There was snow locally too, and the 5 inches on the ground in Westerly included waist-deep drifts. There were only a few days to clear it before crowds started arriving.

Foster farm off Beach Street was picked as the viewing spot for out-of-towners in Westerly. Landowners opened other properties, including Cochegan Rock farm in Montville and a stretch on Hinckley Hill in Pawcatuck.

The railroad sold over 2,000 tickets, and Westerly anticipated a huge influx from Providence and Boston. The marquee visitor was expected to be inventor Thomas Edison, but he was a no-show.

“Let our guests have our first attention in every way,” the Westerly Sun exhorted. “Let people be courteous in the willingness to help.”

New London recruited Boy Scouts to meet arrivals from Worcester and direct them up State Street to Williams Memorial Park.

Power companies thought the brief darkness would cause a spike in demand as people turned on lights, but the opposite view was more realistic. A Yale astronomer urged cities and towns to turn off streetlights to improve the view.

“To see it properly, there should be no lights, no moving about and no noise,” Ernest W. Brown wrote.

The trolley company planned to halt service so passengers could watch, and drivers were urged to pull over in the dark. Stores would wait until after the mid-morning event to open.

On Jan. 23, the Mariners Savings Bank in New London handed out free “eclipse-o-scopes” for safe viewing. An ad in The Day proclaimed that two great events would occur in tandem: the eclipse and Lyon & Ewald hardware’s closing-out sale (“which will also never come your way again”).

Weather remained a question mark, and in his column, Latimer cited statistics that New London had been cloudy eight years out of 10 on Jan. 24. But he held out hope.

“It is a very rare thing indeed for the sun to go on strike after it has once begun the labors of the day,” he wrote.

* * *

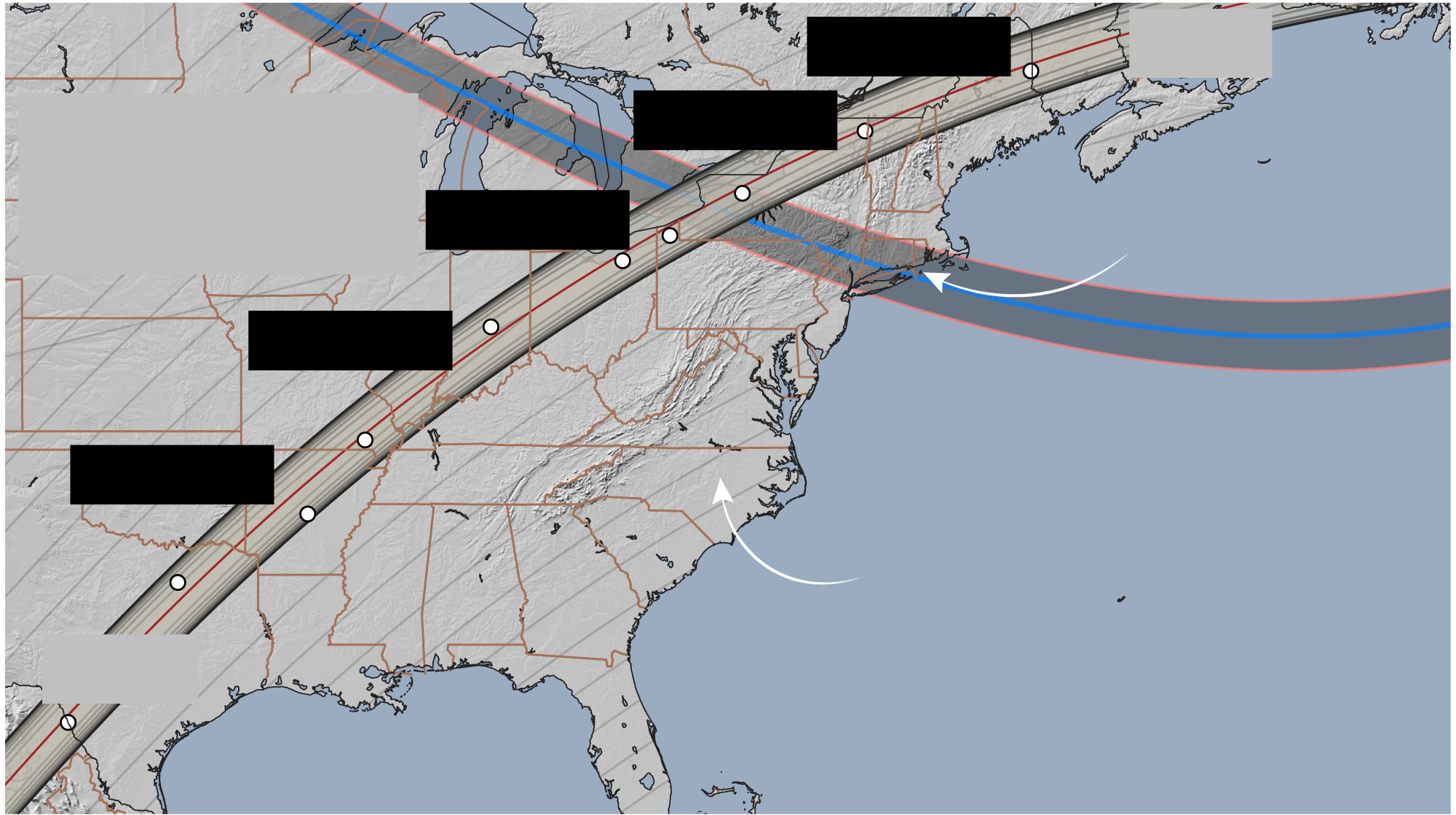

Monday’s event has been called the “Great American Eclipse.” Either partiality or totality will be visible everywhere in the continental U.S., and in Mexico and most of Canada.

2024

Houlton, Maine

3:32:05 EDT

1925

Tale of two eclipses

The path of the Moon’s shadow across the U.S. Monday just skirts Connecticut. It was a different story Jan. 24, 1925, when the state was squarely in the path of totality.

Plattsburgh, N.Y.

3:25:43 EDT

Cleveland

3:13:45 EDT

New London

95%

1925

Indianapolis

3:06:06 EDT

90%

85%

80%

Little Rock, Ark.

1:51:21 CDT

Skywatchers in Connecticut should see a good show Monday, depending on cloud cover. Using data from NASA, this shows the “contours of obstruction” -- the percentage of the Sun’s area covered by the Moon -- by location. For Connecticut, that’s between 90% and 95%.

2024

Maps: Scott Ritter/The Day | 2024 eclipse data from NASA; 1925 data from Xavier Jubier’s “Five Millennium Cannon of Solar Eclipses Database;” map data: Natural Earth

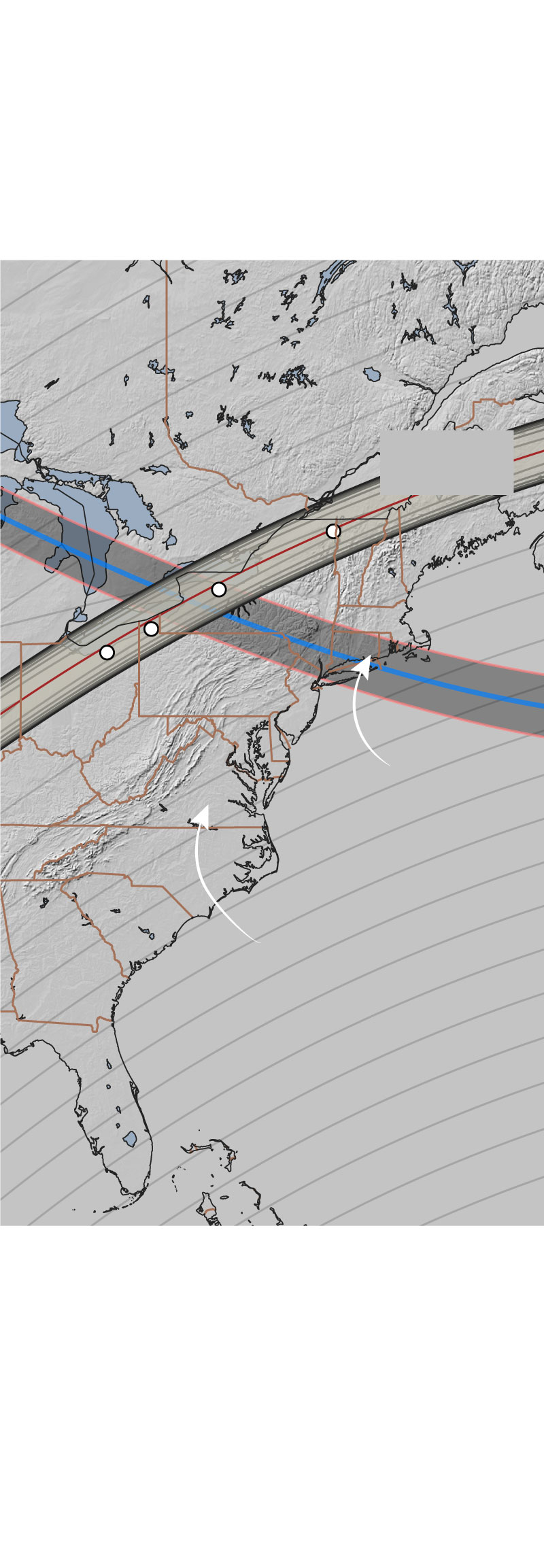

Tale of two eclipses

The path of the Moon’s shadow across the Monday just skirts Connecticut. It was a different story Jan. 24, 1925, when the state was squarely in the path of totality.

85%

90%

2024

95%

1925

95%

90%

New London

85%

Contours of

obstruction

Skywatchers in Connecticut should see a good show Monday, depending on cloud cover. Using data from NASA, this shows the “contours of obstruction” -- the percentage of the Sun’s area covered by the Moon -- by location. For Connecticut, that’s between 90% and 95%.

Maps: Scott Ritter/The Day | 2024 eclipse data from NASA; 1925 data from Xavier Jubier’s “Five Millennium Cannon of Solar Eclipses Database;” map data: Natural Earth

Beginning in the Pacific, the eclipse will travel northeast, reaching the Mexican coast at 11:07 a.m. PDT, according to NASA. It will enter the U.S. in Texas and pass through Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine.

In southeastern Connecticut, we’ll see just under 90% totality, NASA says. The moon will begin to cover the sun at 2:14 p.m., obscuring all but a thin crescent by 3:28. Then it will move away, and by 4:38, the eclipse will be over.

The forecast calls for sunny, delightful weather with a high temperature of 57 on the shore and 62 inland. Fingers crossed.

If things don’t work out, there will be other partial eclipses in Connecticut over the next few years, but if you want totality without traveling, that won’t happen till May 1, 2079.

Mark your calendar.

* * *

The wind in Lakehurst died down early on Jan. 24, and ground crews walked the giant Los Angeles out of the hangar. Its helium-filled bulk rose at 5:22 a.m., more than two hours late. As a result, its destination was changed from Nantucket to Block Island.

In Duluth, Minn., the sun rose already eclipsed, then the phenomenon started its eastward trek over the Great Lakes and into New York.

The southern edge of the totality zone was expected to divide northern Manhattan, and speculation abounded on where exactly the line would be. It ended up falling on 96th Street.

Just north of there, Alexander Calder, a young painter not yet famous for mobiles, saw a crowd watching the sky and captured the scene in an oil on canvas. Another artist, Howard Russell Butler, stood on the roof of a Middletown hotel, also making observations for a painting. Stephen W. Macomber did the same in Watch Hill.

At Conn College, the crowd that shivered in 0-degree air was 1,500 strong and included groups from Harvard and Wellesley who had come in on the special trains. In the distance, they could make out the Los Angeles gliding southeast. The view of the airship was better from Westerly.

Ten thousand people crowded Hosmer Mountain in Willimantic, where conditions were frosty but ideal.

In New London, the sun was hidden, though not in the hoped-for way: Clouds spanned the sky. But at 8:03 a.m., just as the eclipse began, they began to part and a few minutes later were out of the way. Leon Campbell from Harvard started taking pictures.

The path of Monday’s solar eclipse is shown in grey. The 1925 eclipse, in blue, crossed directly over Connecticut.

In Williams Memorial Park, visitors from Worcester waved arms and stamped feet against the cold. The Day described the crowd as “beautiful damsels, kaleidoscopic apparel, hundreds of flapping galoshes, cosmetics galore, fur coats of every description, and merry ripples of laughter.”

At 9:13 the last sliver of sun was extinguished by the moon, and night reigned for 110 seconds. Mercury, Venus and Jupiter appeared in the sky. Multicolored waves of light shot up from the horizon amid “oohs” and “ahhs.”

The moment passed as quickly as it had arrived. Frozen spectators got back on their trains and left town. The Los Angeles flew back to Lakehurst, its mission a disappointment. Wind had buffeted the ship, and photos turned out blurry.

Rosa Ponselle, star soprano of the New York Metropolitan Opera, should have been long gone from New London. But a few days earlier, she had fallen ill en route to her appearance in the Connecticut College Concert Series and was recovering at the Mohican Hotel. She saw the eclipse from there. “It’s grand,” she said simply.

It wasn’t grand for deer at the Bronx Zoo, which tumbled over one another in terror. Monkeys ceased chattering in awe, and birds fell asleep.

A few humans were similarly disoriented. A man in New Jersey stared directly at the sun and claimed it cured his vision, which had been clouded by cataracts. A Middletown woman suffered an emotional collapse and was unconscious for hours. An elderly barber at the U.S. Capitol ran amok with a razor, fearing the end of the world.

For most, the experience was less extreme.

“The whole affair was ‘perfect,’ exactly on schedule, and full of more wonders … than ordinary folk can ever forget,” Latimer wrote. “It is too bad we won’t have another locally in our lifetimes.”

j.ruddy@theday.com

Comment threads are monitored for 48 hours after publication and then closed.