This story is a collaboration with Biography.com.

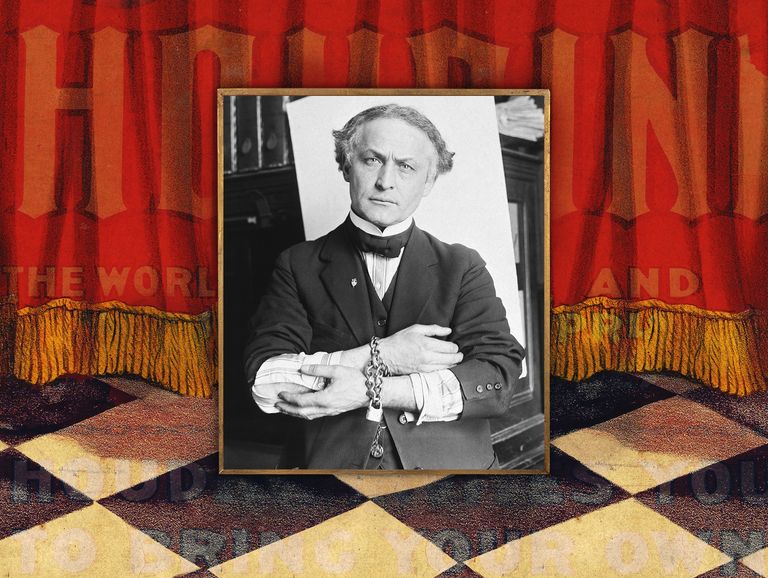

One hundred and fifty years ago this month, on April 6, 1874, the legendary illusionist Harry Houdini was born in Appleton, Wisconsin.

Or so he claimed.

The man we call Houdini was actually born Erich Weisz on March 24, 1874, in Budapest, Hungary. He did grow up in Appleton, as one of seven children to Rabbi Mayer Samuel Weisz and his wife, Cecelia, so Houdini’s professed Wisconsin heritage isn’t a total fabrication—just a little bit of misdirection, like he would use in one of his famous sleight-of-hand tricks.

From the very beginning, Harry Houdini’s life was never quite what it seemed. And, as it turns out, neither was his death.

Harry Houdini’s Cause of Death

Harry Houdini, the world’s most famous magician, died in Room 401 of Grace Hospital in Detroit, Michigan, on October 31, 1926—fittingly, Halloween. The 52-year-old’s cause of death was, according to Biography, “peritonitis from a ruptured appendix.”

For many fans, it was hard to believe. After all, “defying death” was a signature element of Houdini’s act. When he began his career in 1894, “his magic [was] met with little success,” but Houdini “soon drew attention for his feats of escape using handcuffs.” Biography attributes Houdini’s escape skills to “both his uncanny strength and his equally uncanny ability to pick locks,” noting that rather than rely on a gimmick, “Houdini’s feats would involve the local police, who would strip search him, place him in shackles, and lock him in their jails.”

He escalated his performances from handcuffs and straitjackets to locked, water-filled tanks and sealed packing crates. His escape acts eventually incorporated elaborate props, such as his renowned Chinese Water Torture Cell and the Milk Can Escape.

Just as audiences were amazed by Houdini’s incredible escapes and puzzled over the secrets behind his tricks, many found it hard to believe that a ruptured appendix could take the life of a man who so regularly seemed to cheat death on stage. In the same way that a “volunteer from the audience” might search a box used in a sawing-a-woman-in-half trick for a trap door, people started to seek explanations other than the official cause of death to make sense of Houdini’s sudden demise.

As the U.S. transitioned from the 19th to the 20th century, Americans often looked for clear-cut explanations for tragedies, preferring to pin the blame on a single “culprit” rather than accept the inexplicable. Someone, or something, had to be responsible, and this quest for accountability led to popular scapegoats.

For example, we still blame Mrs. O’Leary’s cow for starting the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, even though it was officially cleared of any wrongdoing in 1997. And the 1997 blockbuster Titanic perpetuated the false narrative that J. Bruce Ismay, the highest-ranking White Star Line official to survive the ship’s sinking, was a coward who contributed to its fatal encounter with the iceberg. However, as the Titanic Historical Society points out, the reality is quite different: “The truth was Ismay helped with loading and lowering several lifeboats and acquitted himself better than the behavior of many of the crew and passengers.”

So, the official cause of Harry Houdini’s death was a ruptured appendix. But early 20th century Americans craved a more sensational story, one that pointed a finger at a culprit. And they got two versions: an explanation that implicated a mysterious man, and another that hinted at a sinister conspiracy.

The Man Who “Killed” Harry Houdini

You might have heard the simplified version of how Houdini died: he was unexpectedly punched in the stomach. However, the identity of the person who delivered the fatal punches isn’t widely known, which has led to many myths and fabrications. Some say the puncher was a professional boxer (he wasn’t), while others suggest he was a hitman hired by fraudsters or Spiritualists (there’s no evidence to support this).

You would expect that, nearly 100 years later, the man who allegedly dealt the abdominal blows that killed the world’s most famous magician would be infamous, with his life examined as closely as those of Lee Harvey Oswald or Mark David Chapman. However, surprisingly little information is available about J. Gordon Whitehead.

We know that at the time of the incident, Whitehead was a student at McGill University. Houdini had given a lecture at the university a few days earlier and had invited some students to see him in his dressing room on October 22 at the nearby Princess Theater.

As HISTORY recounts:

“At some point, a student named J. Gordon Whitehead arrived and asked Houdini if it was true that he could resist hard punches to his abdomen—a claim the magician had supposedly made in public.”

Houdini, reclined in a seat at the time, said that was true. Then, as witness Sam Smilovitz described, Whitehead swiftly delivered “four or five terribly forcible, deliberate, well-directed blows” before the magician had time to prepare. The punches left Houdini in noticeable pain, which persisted in the days to come.

Less than two weeks later, Houdini would be dead. But what happened to Whitehead?

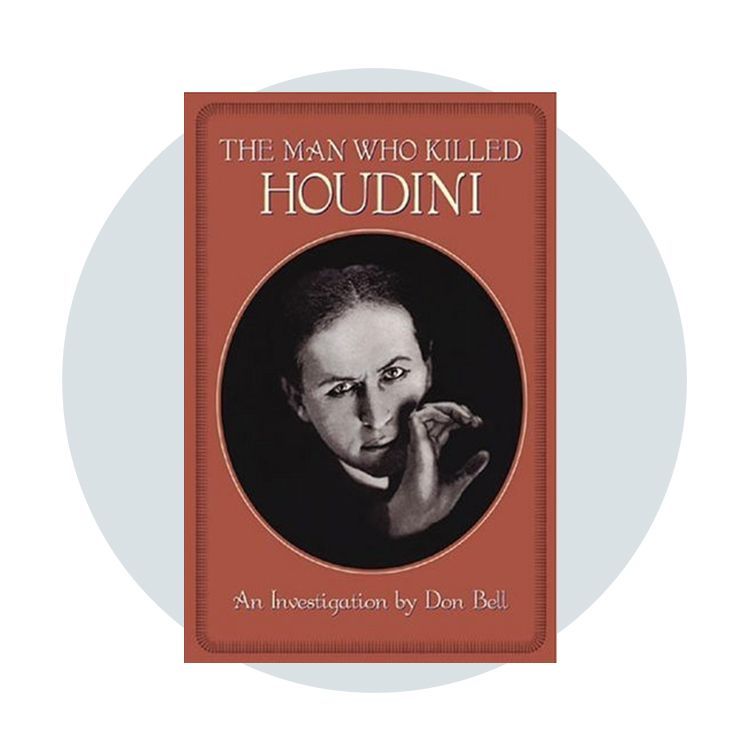

The most comprehensive research on J. Gordon Whitehead can be found in Don Bell’s 2005 book, The Man Who Killed Houdini. It reveals details not included in the widely accepted story of Houdini’s death, including other occasions in Montreal where Houdini withstood punches prior to the encounter with Whitehead. Bell also visited the grave of Whitehead, who died three decades after the incident with Houdini, and found the only known photograph of the man associated with Houdini’s death.

Despite Bell’s thorough investigation, information about Whitehead remains scarce. And so, the limited facts available leave ample room for suspicion, suggesting that Whitehead could have been more than just an impulsive college student ... and that he might not have acted alone.

Who Wanted Harry Houdini Dead?

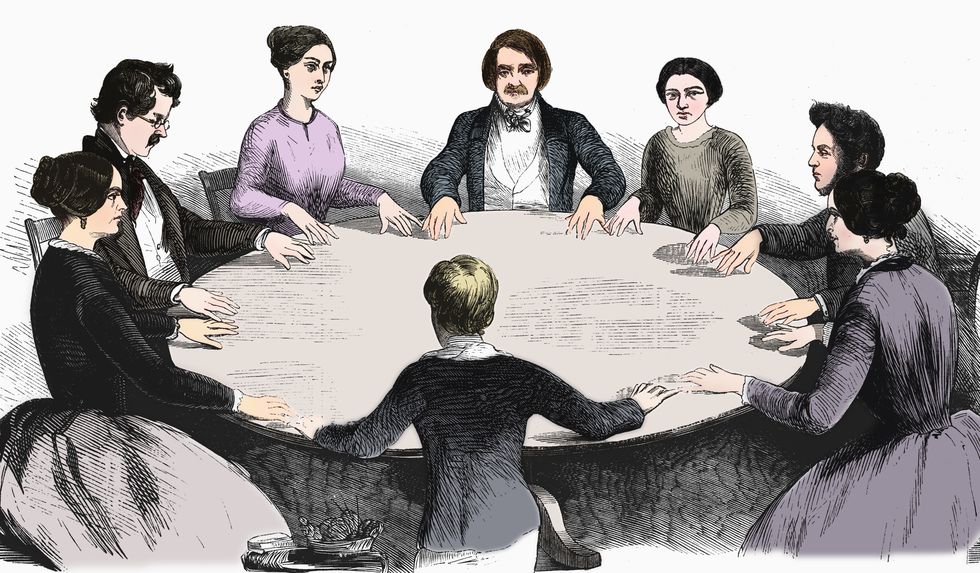

In our modern times, “spiritualism” has become a catch-all term, a philosophical descriptor for belief in anything beyond the material world. But in the early 20th century, Spiritualism was big business.

The shadow of death loomed large in America during the late 1800s. The Civil War had taken more than 620,000 lives from both the North and South, leaving countless people yearning for a way to connect with the souls of their lost loved ones and to hold onto the hope of an afterlife.

Spiritualism, a movement that involved mediums holding séances to “speak to the dead,” blossomed in America at the time thanks to a combination of contemporary religious philosophies from thinkers like Emanuel Swedenborg and Franz Mesmer, and parlor trick showmanship, as these mediums relied on “signs” like knocking on walls and conveniently snuffed-out candles to show their paying customers that “spirits were present.”

“By the end of the war,” an article on AustinTexas.gov notes, “...a reported 11 million people subscribed to Spiritualism and 35,000 were practicing medium.”

In the wake of the Civil War, Spiritualism was as widespread as it was lucrative. And like any other aspect of American life in the so-called Gilded Age, if there was an unregulated way to make a profit, unscrupulous figures would flock to it.

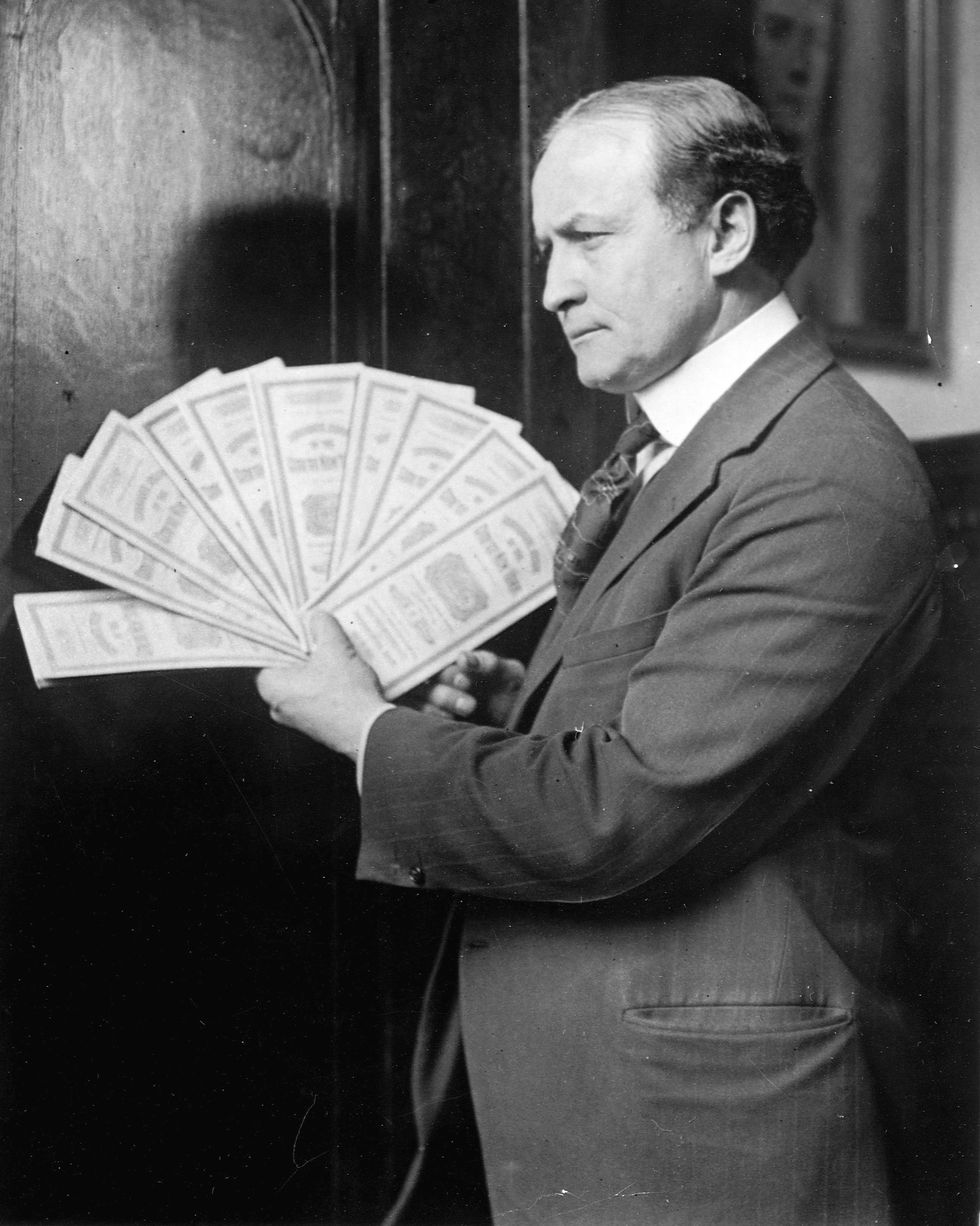

Harry Houdini personally detested Spiritualists, making it his life’s mission to debunk them. As Biography notes:

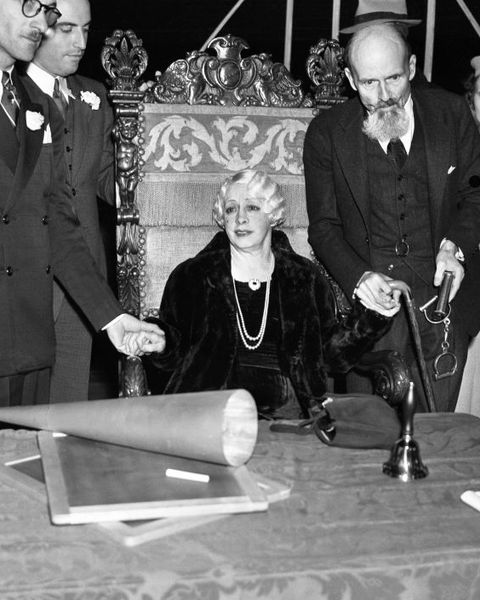

“As president of the Society of American Magicians, Houdini was a vigorous campaigner against fraudulent psychic mediums. Most notably, he debunked renowned medium Mina Crandon, better known as Margery.”

Margery, a 36-year-old who claimed to have psychic powers, drew Houdini’s scrutiny because she was a frontrunner for a $2,500 Scientific American magazine prize. This prize was promised to any medium who could convincingly demonstrate psychic abilities under controlled tests. By 1924, the income potential for mediums had grown—it wasn’t just about taking money from grieving people anymore. With a legitimate publication like SciAm offering over $45,000 in today’s money for real psychic proof, the incentive for those staging fake supernatural events increased dramatically—perhaps enough to be willing to kill.

Houdini was on the committee that examined Margery’s psychic claims and he strongly condemned her as a fraud. Before Scientific American could formally dismiss her, Houdini proactively released a pamphlet discrediting her, and even staged a public exposé at Boston’s Symphony Hall to reveal her deceit, all with his own money.

Houdini put his proverbial, and literal, money where his mouth was when it came to debunking Spiritualists. “It takes a flimflammer to catch a flimflammer,” he once told the Los Angeles Times. But Houdini’s campaign against fraudulent psychics didn’t just cost him money; it also cost him his friendship with author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a devoted Spiritualist.

Houdini’s efforts also cut deeply into the income of the organized crime groups that profited from the unregulated Spiritualist industry, which exploited grieving people. This has led some people, including Bell, to speculate that Whitehead might have been following orders from those involved in the Spiritualist scam, suggesting his punches weren’t accidentally lethal, but were deliberately meant to kill Houdini.

Indeed, in 2006’s The Secret Life of Houdini, authors William Kalush and Larry Sloman take this speculation a step further, asserting that Houdini wasn’t fatally punched by Whitehead at all, but rather, that he had been slowly poisoned over time, a tactic they say Spiritualists had previously used to silence their opponents. As evidence, Kalush and Sloman point out that an autopsy was never conducted on Houdini, which means the exact cause of his death was never officially confirmed.

How Did Harry Houdini Actually Die?

J. Gordon Whitehead’s punches didn’t directly cause Harry Houdini’s ruptured appendix. A 2013 article in the World Journal of Emergency Surgery noted that “blunt abdominal trauma leading to appendicitis is rare.” If someone wanted to murder Houdini, trying to burst his appendix with punches would be a poor plan of attack. Additionally, the suggestion that Houdini might have been poisoned, based solely on the absence of an autopsy, is speculative at best. It essentially argues that without an autopsy, you can’t rule out poison, which certainly isn’t the solid evidence Houdini would have demanded when investigating a claim.

So, what really killed Harry Houdini? Much like trying to figure out a magic trick, it’s best to not get swept up in the fanciful story the magician is telling, and instead, keep an eye on the hand he’s hiding at his side, out of the spotlight.

Harry Houdini was seated when Whitehead struck him. Why? Because several days prior, as HISTORY notes, during a performance on October 11, 1926, Houdini had fractured his left ankle while performing his Chinese Water Torture Cell, and “hobbled his way through the rest of the show.” Houdini was in Montreal despite his doctors advising against it. Determined that “the show must go on,” he chose to endure his pain in private, which is why he was sitting down in his dressing room when the McGill students visited.

If Whitehead played any real role in Houdini’s death, it was that his punches gave Houdini a reason to dismiss the abdominal pain he felt afterward. Houdini used this excuse to reassure himself and his worried wife, Bess, which led him to continue his tour to Detroit. He ignored the true cause of his symptoms—a ruptured appendix, not the punches. Houdini’s determination to perform meant he delayed seeking medical help until it was too late. By the time surgeons operated to remove his appendix, the infection had spread too far.

Was Houdini’s Death Really “The End”?

In his life, Houdini escaped from milk cans, water tanks, and prison cells. But in the act of dying, did Houdini achieve the “ultimate escape,” one of his soul from the flesh-and-blood prison of his own body?

In spite of his many crusades against Spiritualists, Houdini didn’t completely discount the possibility of life after death. And if anything at all could endure after his heartbeat ended, it was his love for Bess, the girl from Coney Island who stole his heart and became his stage assistant and devoted lifelong companion.

“Houdini and his wife did in fact experiment with otherworldly Spiritualism when they decided that the first of them to die would try to communicate from beyond the grave with the survivor,” Biography notes. They devised a secret code that only they knew: The surviving partner would participate in yearly séances with different mediums, hoping to find one who could genuinely reach the dead and deliver the secret message that only their departed loved one would know.

The surviving spouse had to hope to hear, “Rosabelle—answer—tell—pray answer—look—tell—answer answer—tell.” The first word was the title of a song the couple would perform in the early days of their routine together in Coney Island (a love song with a story that isn’t quite so romantic a century later), and they developed the rest of the code words for the “mentalist” portions of their performances, where each word corresponded with a letter, in this case spelling out, “BELIEVE.”

In the 10 years after Houdini’s death, Bess held annual séances, but she never heard that phrase. “Before her 1943 death,” Biography notes, “Bess Houdini declared the experiment a failure.”

As the World Journal of Emergency Surgery article suggests, it’s highly unlikely—but not impossible—that a fatal flurry of punches struck down Houdini. And it’s highly unlikely—but not impossible—that anyone was “behind” the death of Houdini besides Houdini himself, neglecting his health in favor of putting on a good show. And the Houdinis’ failed experiment suggests that it’s highly unlikely—but not impossible—that a conscious part of the magician survived beyond October 31, 1926.

The enduring interest in these theories, and the fact that people continue to explore them nearly a century after Houdini’s death, drive home the magician’s true lasting legacy: He made us all reconsider what we would otherwise deem “impossible.”

Michael Natale is the news editor for Best Products, covering a wide range of topics like gifting, lifestyle, pop culture, and more. He has covered pop culture and commerce professionally for over a decade. His past journalistic writing can be found on sites such as Yahoo! and Comic Book Resources, his podcast appearances can be found wherever you get your podcasts, and his fiction can’t be found anywhere, because it’s not particularly good.