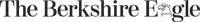

A Berkshire Evening Eagle clip from Jan. 1, 1916, hypes the upcoming screening of the D.W. Griffith film "The Birth of a Nation," which portrays the Ku Klux Klan as a heroic force.

At noon on a Friday, two men in the robes of the Ku Klux Klan rode their horses down Pittsfield’s North Street.

The date was Jan. 7, 1916, and they were heralding the debut of D.W. Griffith’s film “The Birth of A Nation” at the Majestic Theater. The film’s arrival had been hyped for weeks, and hundreds had already bought tickets to the controversial epic.

The theme was not unfamiliar to local attendees — its source material, Thomas Dixon’s “The Clansman,” had been performed for the stage multiple times at Pittsfield’s Colonial Theatre, and the Empire in North Adams. Despite the promotional theatrics, most northern moviegoers assumed the KKK — depicted so favorably in the film — were a fraternity long since vanished.

Hardly anyone knew that six weeks earlier in Georgia, William Simmons led a group up Stone Mountain after viewing the film, and declared himself Grand Wizard of a new KKK.

This regime remained relatively small for the first several years, but grew rapidly in the early 1920s, to a peak of about 4 million members, or up to 15 percent of eligible Americans.

In some ways, the new order operated as a multilevel marketing scheme — new members paid steep dues of $10 per year, out of which the person who recruited them kept a percentage, kicked some up to their local and regional “kleagles,” and sent half to the national office.

The money-hungry cause was happy to customize its message of who was ruining America to local prejudices and demographics — in Pittsfield, it beat the drum of anti-Italian sentiment; in Williamstown, the message seemed to be focused on the black community in White Oaks.

Members met at White Oaks Congregational church, Whitcomb Summit, and at Prospect Lake Park in Great Barrington. They met at Red Bat Cave in New Ashford, at the Rice Farm near the site of the North Adams Walmart, at the Odd Fellows hall in Pittsfield, and even the Otis Town Hall.

When denied space to meet, the organization was quick to claim it as discrimination against members as native-born white protestants, what they referred to as “100 percent Americans.”

In the 1941 book "Mind of the South," journalist W.J. Cash described this second Klan as ”anti-Negro, anti-Alien, anti-Red, anti-Catholic, anti-Jew, anti-Darwin, anti-Modern, anti-Liberal, Fundamentalist, vastly Moral, militantly Protestant. And summing up these fears, it brought them into focus with the tradition of the past.”

A headline in the North Adams Transcript from May 1926 tops a story about a large meeting of the Ku Klux Klan in New Ashford.

At least some of these fears struck chords with locals. Some residents blamed immigrant groups for the rise in violent crime and narcotics in the Berkshires, for expanding socialism and labor flare-ups like the bitter GE strikes of the late 1910s, and for the perceived collapse of family harmony (the 1920s saw record levels of divorce). To these concerns, the Klan offered platform slogans of “America First,” fixing “the immigration nightmare,” and “the protection of pure womanhood.”

By the mid-1920s, it was holding nighttime “konklaves” with anywhere from 1,000 to 1,500 local men, inducting hundreds of new members in a single cross-burning ceremony. When you look at the 100,000 population of the county at the time, and subtract all the people who weren’t allowed to be there, it starts to look like it may have been around 15 percent of eligible men in the Berkshires, as well.

In 1924, locals were among 15,000 who attended an October Klan rally in Worcester that descended into rioting. Thousands more gathered in Charlemont, at the Deerfield Valley Fair Grounds, two years later. Outsiders were banned, and newspaper photographers who attempted to get close to gatherings were treated roughly.

While the local chapters were sometimes implicated in “White Cap”-style intimidation, the new Klan took a more organized tact, and soon was exerting influence on various town elections. The 1925 elections in Buckland and Shelburne Falls were completely dominated by Klan discussions, with Klan-friendly candidates elected in both towns by narrow margins.

In Hancock, February 1927 saw a longtime incumbent town clerk ousted in favor of the Klan-backed candidate Harry K. Hinds. The same week, a cross was burned in White Oaks after the favorable outcome of polls in Williamstown.

By 1930 the organization was again in decline, in part due to internal strife within the national pyramid scheme, and they withered out by the 1940s. A third KKK reemerged during the Civil Rights struggles of the 1950s and '60s, but remained much smaller, and largely confined to the South.

But in 1966, a cross was burned on the lawn of NAACP organizer Lawrence Caesar in Dalton; another was lit in front of the Black Students Union at Williams College in 1980.

These days, people around here don’t tend to express political sentiments by setting things on fire … save maybe for the occasional hay bales. Hoods are unnecessary in a world of electronic communication that offers so much anonymity, where insurrections can be coordinated via phone apps.

It’s not the hoods and the crosses, but the often-veiled messaging that demands vigilance. The attitudes and the xenophobia behind the words are as alive as ever.