The world's strangest economies that have experts BAFFLED

Economic oddities from around the globe

maloff/Shutterstock

Some of the planet's economies are downright bizarre. Did you know, for example, that one nation makes most of its money from an internet domain name?

From an economy skewered by multinationals to one that's massively affected by the price of milk, read on to discover the world's top 10 most unusual economies. All dollar amounts in US dollars unless otherwise stated.

Tuvalu

Mario Tama/Getty Images

As economic mainstays go, this is one of the most curious: an internet domain name. The tiny Pacific island nation of Tuvalu, which has a population of just 11,000, is making millions by licencing out its lucrative .tv URL suffix.

The country was assigned the serendipitous suffix, coincidentally the worldwide abbreviation for television, in 1995 – and hasn't looked back. In the late 1990s, Tuvalu's government teamed up with a Californian firm and finalised a $50 million (£40m) leasing deal, which was transferred in 2001 to a company called Verisign.

Tuvalu: internet domain moneyspinner

Sharaf Maksumov/Alamy

The island nation made around $2 million (£1.6m) a year from the Verisign deal up to 2011, when the annual payment increased to $5 million (£4m). Thanks to the success of Twitch.tv and the proliferation of streaming services, the .tv suffix soared in prestige and value during the 2010s.

Luckily for Tuvalu, its contract with Verisign came up for renewal in 2021. Capitalising on the popularity of the domain name, the country wasted no time signing a plum deal with GoDaddy that's estimated to be worth $10 million (£8m) a year. This represents a sixth of the nation's GDP.

Tuvalu: key government funding source

maloff/Shutterstock

The windfall has been a boon for the country, funding everything from hospitals and schools to road paving schemes and the expansion of the electricity grid. Tuvalu's government is even using some of the proceeds to help bankroll its Future Now Project, which aims to mitigate the effects of climate change. (The nation is one of the world's fastest-sinking countries and risks being completely wiped out as a consequence of rising seas.)

And Tuvalu isn't the only country that's got lucky with its domain name; Anguilla has recently started cashing in on its .ai suffix, which is on fire amid the artificial intelligence boom. The Caribbean territory is reportedly making a tidy $3 million (£2.4m) a month by licensing the letters, which is around a third of the government's monthly budget.

Djibouti

YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP via Getty Images

One of Africa's smallest sovereign states, Djibouti has a population of only 990,000. Trade is the country's economic bedrock, but weirdly, it's another nation's trade that underpins the economy.

According to the World Bank, the country is powered by “a state-of-the-art port complex, among the most sophisticated in the world.” This complex handles an estimated 95% of Ethiopia's international trade, hence its importance.

Djibouti: trading conduit for Ethiopia

Dereje Belachew/Alamy

The bordering nation of Ethiopia is landlocked. For years, the country has been reliant on Djibouti to take care of its maritime trade, with the country's ports acting as a conduit for Ethiopia's exports (mainly coffee) as well as its numerous imports.

Ethiopia's economy dwarfs Djibouti's, with respective GDPs of $120.37 billion (£95bn) and $3.66 billion (£3bn) in 2022, according to Statista. It makes sense, then, that Ethiopia's trade activities dominate the port complex – especially as 80% of the country's manufacturing and services sectors are totally dependent on port activities.

Djibouti: threats to the economic mainstay

Mohammed Hamoud/Getty Images

Djibouti may come to regret putting all its eggs in one basket, though. While the country's status as a trading hub has benefited of late from factors such as China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which has seen a huge amount of Chinese investment in the tiny African nation, its economic success is closely intertwined with Ethiopia's – for better and worse.

Moreover, Djibouti's ports have suffered as a result of the Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping. The latest threat is a proposed deal between Ethiopia and Somaliland, which could see Somaliland all but replacing Djibouti as Ethiopia's maritime trading hub, spelling catastrophe for the Djiboutian economy.

Guyana

SINCHAI_B/Shutterstock

The world's fastest growing economy, Guyana is in the midst of an astonishing economic boom. Last year, growth came in at a sensational 33% and is expected to top that figure through 2024. No other economy's performance even comes close.

Guyana owes its bonanza to vast oil reserves that have been discovered in recent years by a consortium led by ExxonMobil. The first deposits were pinpointed in 2015, and the US fossil fuel giant began production in the country in 2019.

Guyana: the oil bonanza in numbers

MJ Photography/Alamy

Guyana's oil production stood at just 1,200 barrels a day in 2019. The number has since skyrocketed to around 645,000.

Guyana has never been so flush with money. To date, the 21st century oil rush has made the country $3.5 billion (£3bn) according The New York Times, and the government predicts annual oil revenues of $10 billion (£8bn) by 2030.

Guyana: spending the proceeds wisely

LUIS ACOSTA/AFP via Getty Images

President Irfaan Ali says the proceeds are being spent on investing for the future and improving Guyana's infrastructure, healthcare, education, and agriculture. The powers-that-be have even pledged to fund projects that mitigate climate change, offsetting the damage the oil causes... to a limited extent.

In other words, the Guyanese government is going all out to avoid the dreaded resource curse. Also known as the paradox of plenty, the 'resource curse' is a phenomenon whereby countries with bountiful natural resources end up experiencing less growth or development than countries with fewer resources.

Having created a natural resource fund, the authorities will judiciously invest oil revenues rather than fritter them away, probably taking at least some of its cues from Norway...

Norway

dpa picture alliance archive/Alamy

Norway's economy has long been considered 'weird' among economists because, for one reason, it's avoided falling prey to the all-too common resource curse, making it a stark outlier.

This tends to happen when resource-rich countries focus all their energy on one commodity, which can leave their economy at the mercy of its boom and bust cycles, and sapped by low growth over the long-run. Norway could have easily squandered its oil and natural gas, which were discovered in significant quantities in 1969. Instead, the Nordic nation took the sensible approach.

Norway: oil economy stewardship

dpa picture alliance archive/Alamy

Guided by the government's 10 Commandments of Oil, a concerted effort was made to develop the sector to be as economically sustainable as possible, while considerable portions of the proceeds have been funnelled into the country's famed sovereign wealth fund. Now the largest sovereign fund in the world, it's currently valued at an astronomical $1.4 trillion (£1.1trn).

The Norwegian economy is also known for its paradoxes or puzzles.

Norway: economic paradoxes

Alexandre Patchine/Alamy

For instance, the country enjoys high levels of productivity and an ever-buoyant economy despite relatively scant research and development investment, an enigma that has bewildered economists for years.

Other contradictions include Norway's decision to embrace green energy and electric vehicles in spite of its role as a major producer and exporter of oil and natural gas.

North Korea

VLADIMIR SMIRNOV/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

North Korea's economy is strange for many reasons – not least of which is the extraordinary control the Kim Jong-un regime exerts over it.

The country's Soviet-esque command economy (an economy where production is closely controlled by the government) is in fact the most closed-off in the world. Unlike other command economies, which have either gone extinct or been watered down with capitalist principles, North Korea's is becoming even more centralised and Stalinist.

North Korea: return to a Soviet-style command economy

ANTHONY WALLACE/AFP via Getty Images

The market-oriented reforms that boosted the economy in the 2000s and much of the 2010s have been harshly reversed as the North Korean regimes tightens its grip, leading to untold suffering for the population.

Following the almost total closure of the country's borders, ostensibly to prevent the spread of COVID-19, basics have become hard to come by. Although North Korea was fortunate to have a good harvest in 2023, which has alleviated the crisis to some extent, starvation is a harsh reality for many citizens.

North Korea: economy going backwards

Jon Arnold Images Ltd/Alamy

As the rest of the world moves forward, North Korea is regressing, according to Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein of the Swedish Institute of International Affairs.

With the focus now shifted to heavy industry, the country has stepped into an economic time machine. Trade with Russia has grown since Putin's unlawful invasion of Ukraine, harking back to the days of the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, China is North Korea's only other significant trading partner, recalling the situation in the late 20th century.

Iran

SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images

Like North Korea, Iran is regarded as a pariah by the civilised world and has been subject to punishing sanctions for decades.

The first sanctions were imposed by the US in 1979 amid the Islamic Revolution. Over the years, the West has levied further sanctions. They were waived for a time as part of the Iran nuclear deal, but President Trump had the US sanctions reinstated in 2018 and added further restrictions in 2019 and 2020.

Iran: record low rial/US dollar exchange rate

ATTA KENARE/AFP via Getty Images

The sanctions the West has imposed have been incredibly damaging to Iran's economy and have created a number of distortions. Take the country's currency, the rial.

Back in 1978 before the Ayatollahs took power, 70 rials bought one US dollar. Fast-forward to 2024 and the currency has plunged to record lows. At the time of writing, 1 rial is worth $0.000024.

Iran: world's weakest currency

ATTA KENARE/AFP via Getty Images

Adding to the pressure of strict sanctions, the rial has been racked by political unrest in the country and rampant inflation these past couple of years.

At one point this year it nosedived to 606,000 rials to the US dollar as per the open market exchange rate. This makes the rial the world's weakest and least valuable currency.

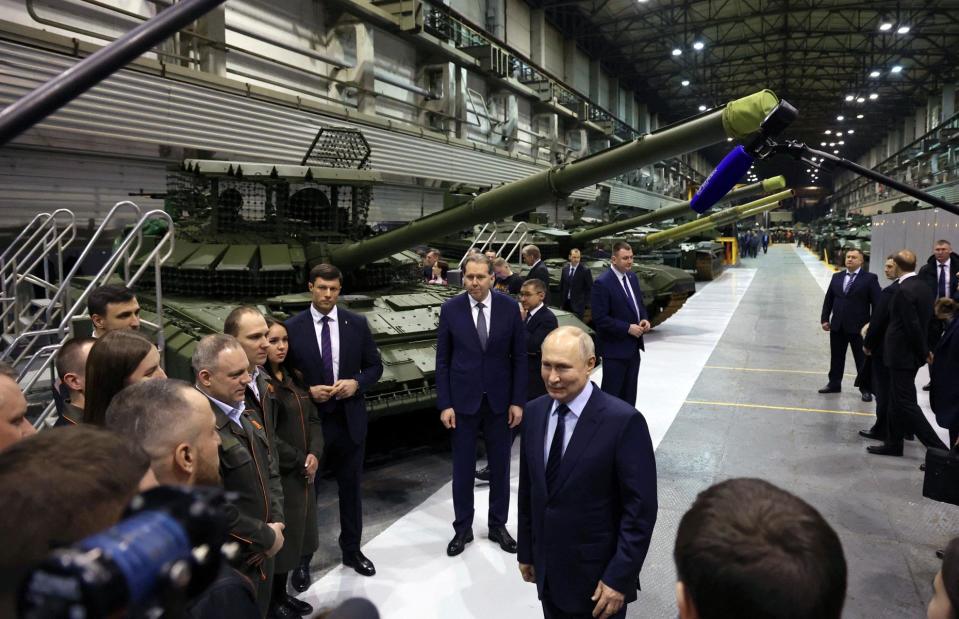

Russia

ALEXEY NIKOLSKY/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

In marked contrast to North Korea and Iran, Russia seems to be doing just fine – despite becoming the world's most sanctioned country following its invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The long list of Western trade restrictions was meant to bring Putin's regime to its knees. But the country's economy appears to be ticking along very nicely indeed, growing by as much as 3.6% in 2023.

So what's behind this weird contradiction? Shouldn't the Russian economy be on the verge of collapse?

Russia: economic resilience

NATALIA KOLESNIKOVA/AFP via Getty Images

The Russian government has found new trading partners such as China and India for its key commodities, including oil and natural gas. What's more, a significant number of Western companies have chosen to stay put in Russia – and many of those that did quit have simply been replaced by local copycats. For example, McDonald's has become Vkusno i tochka, Starbucks has become Star Coffee, and Zara has become Zarina.

What's more, Moscow has managed to sidestep some of the Western sanctions by trading through intermediaries and engaging in other shady schemes. And crucially, it's enormously ramped up its defence spending, which has been fuelling the domestic economy.

Russia: unsustainable economy

ALEXANDER KAZAKOV/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Those who were hoping for a swift collapse of the Russian economy are no doubt disappointed. That said, a slew of economists suggest Russia's economic success is likely to be short-lived.

The country has had to offer discounts on its oil and natural gas exports, and these price markdowns aren't sustainable going forward. Long-term, Russia's OTT military spending won't be possible to maintain either, meaning the country could find itself in dire economic straits in the not-too-distant future.

Ireland

David Creedon/Alamy

The weirdness of Ireland's economy came to the fore in 2016 when the country posted mind-boggling growth of 26%, later revised up to 34.4%. Half of this was attributed to the fact that Apple had moved its intellectual property to the country.

Dubbed 'leprechaun economics' by economist Paul Krugman, this skewering of GDP by foreign multinationals has characterised Ireland's economy in recent years.

Ireland: heaven for multinationals

Madrugada Verde/Shutterstock

Ireland is blessed with a disproportionate number of large, mainly American, multinationals. Drawn to the country's low corporate tax rates, these major global firms have made the country their HQ and have chosen to report their international earnings and assets there. This artificially distorts Ireland's GDP figures since much of the economic activity hasn't actually taken place in the country.

Still, Ireland's economic success is very real. While more telling measures such as gross national income (GNI) put Ireland's growth closer to its European peers, the figures are impressive nonetheless, with the country consistently ranking among the world's richest and most productive.

Ireland: mutual benefits

Dmitry Kalinovsky/Shutterstock

Drawn to the country on account of its EU membership and highly educated English-speaking workforce, as well as the favourable tax regime, multinationals are producing tangible high-value products in Ireland, from pharmaceuticals to consumer electronics. Plus, the taxes these businesses pay, though comparatively low, are filling Ireland's coffers – so much so the country is running a fat budget surplus.

But will this arrangement last? New global tax rules that force companies to report part of their tax revenues locally, as well as the hike in Ireland's corporate tax rate from 12.5% to 15%, are making the country decidedly less attractive for multinational firms.

New Zealand

Dmitry Pichugin/Shutterstock

Milk is to New Zealand what oil is to petrostates. The country's dairy industry has long been a crucial part of the economy, generating annual revenues of $6.8 billion (£5.4bn) and accounting for one in four of New Zealand's exports.

Needless to say, the fluctuating price of milk can have a major effect on the nation's wider economy.

New Zealand: dairy price effect

Naruedom Yaempongsa/Shutterstock

When milk demand is low and prices subdued, New Zealand's export earnings tank and considerably less tax is collected from the country's dairy farmers. With demand for New Zealand's dairy exports low in slumping China, last year dairy cooperative Fonterra slashed the fixed farmgate milk price per kilo to as low as $3.62 (£2.86), which sparked an outcry.

Farmers warned lower prices would result in billions of dollars in lost revenue and cuts that would reverberate across New Zealand's economy.

New Zealand: milk's economic importance

ChameleonsEye/Shutterstock

This just goes to show the importance of milk and other dairy products to the country's economic wellbeing.

Fortunately, things have picked up this year, with the milk price per kilo currently set at between $4.53 (£3.58) and $4.89 (£3.86), so catastrophe appears to have been averted. Meanwhile, China has lifted all tariffs on Kiwi dairy products, and price forecasts are looking good for New Zealand. Rabobank expects the milk price per kilo to rise to $4.68 ($3.70) though 2024.

Bhutan

Kateryna Mashkevych/Shutterstock

Bhutan stands out from other economies due to the way the government measures performance. Instead of concentrating on GDP and productivity, the small Himalayan kingdom of 800,000 people is primarily concerned with gross domestic happiness (GDH).

Bhutan adopted the GDH Index in 2008 when it was written into the country's constitution. It consists of nine domains and 33 development indicators covering living standards, health, education, psychological wellbeing, and more.

Bhutan: gross domestic happiness

Starflector/Alamy

The country's government is devoted to increasing Bhutan's score on the index, which has increased significantly since 2008. This more human-centric approach to economic growth has actually resulted in excellent GDP growth averaging 7.5% a year while reducing poverty, increasing living standards across the board, and protecting Bhutan's culture and environment.

A testament to the success of this ethos, Bhutan has seen poverty plummet and is now the world's only carbon-negative country.

Bhutan: flourishing economy

angela Meier/Shutterstock

The icing on the cake? Bhutan's graduation last year from the UN's Least Developed Country (LDC) category, which it had been stuck in since 1971. Other nations that boast this achievement include Vanuatu, Equatorial Guinea, Samoa, Maldives, Cabo Verde, and Botswana.

Bhutan is now classified as a middle-income country, which is quite the achievement for a once-impoverished country that has chosen to put people over profit.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance