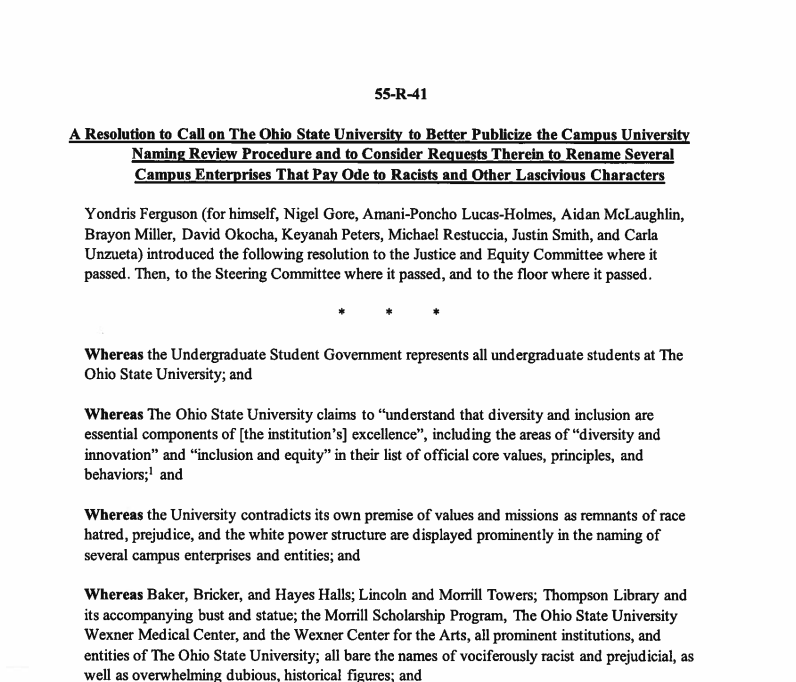

For three years, it was the Undergraduate Student Government’s mission to remove the name of John W. Bricker from Bricker Hall. They even challenged six other buildings for honoring legacies that do not align with Ohio State’s mission of diversity, equity and inclusion. Although Thompson Library is the only official building name change to be requested, three years later, it has resulted in no change.

Amani Bayo

John R. Oller Special Projects Editor

Before he graduated, Yondris Ferguson made it his mission to get Ohio State to remove John W. Bricker’s name from an academic building on the Oval.

“This is a person whose whole career in public service was of no benefit to any marginalized group whatsoever,” Ferguson said.

The campus activist used his platform as speaker of the house in the Undergraduate Student Government to write two of the three resolutions passed regarding the renaming of Bricker Hall and several other buildings between 2021 and 2023, arguing that the legacy of certain individuals was not worth honoring.

“We felt it was counterproductive to the mission of diversity, equity and inclusion that Ohio State prided itself on,” Ferguson said.

Ferguson was not alone. Citizen Advocates for Public Education — an organization that started in 2013 to support public education, quality curriculum learning and teaching experiences — also requested the removal of William Oxley Thompson’s name from the Thompson Library for the leading role he played in segregating Columbus schools.

According to university records, this lone request has been lying in the abyss of Ohio State’s renaming portal for three years.

“They had looked at the evidence that we submitted and they were going to give the request consideration,” said Linda Fenner, Ohio State alum and retired Columbus educator. “That’s pretty much where we are now.”

Though universities across the country— including UC Berkeley, Indiana University, University of Richmond and Yale University — have removed names with a problematic legacy from their buildings, the names of Bricker Hall, the Wexner Medical Center, Thompson Library and four other building names with challenged reputations remain at Ohio State.

“Building name changes is not an erasure of history. We still want the history to be told but we want it to be contextualized.”

— Shira Greer, UNC-Chapel Hill master’s student

“Building name changes is not an erasure of history. We still want the history to be told but we want it to be contextualized,” said Shira Greer, a master’s student at UNC-Chapel Hill and one of the pioneers in the building name changes at Richmond University in 2021.

Despite Ohio State having an official naming portal for students, faculty and alumni to submit renaming requests, university spokespersons said removing a naming designation will occur under exceptional and narrow circumstances.

“The naming review process is thoughtful and thorough and therefore could take several years,” university spokesperson Ben Johnson said.

Former officials in USG, retired long-term Columbus educators and the examples of other universities show the appeal to align namesakes with the values of the institution has yet to result in any change.

Looking into past scrutiny

It wasn’t until the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 that people began to collectively pay attention to the reputations of certain namesakes.

From the removal of the Christopher Columbus statue at Columbus City Hall in 2020 to the 169% increase in chief diversity and inclusion officer positions at the start of the new decade, the world seemed to have mobilized a revolution that acknowledges America’s past.

Within two years, USA Today reported on Nov. 10, 2022, that 82 schools had removed some namesakes as a result of this new call to action.

There are about 133 Ohio State buildings named after an individual, according to Ohio State’s building index. Of those, nine are named after a former university president, 10 after donors or benefactors. The other names are individuals who either held a leadership role at the university, made historical contributions or died honorably.

According to the Naming of University Spaces and Entities from the Office of University Advancement, building namesakes are placed under three categories: administrative — a formal assignment like 18th Avenue Library — honorific and philanthropic naming. The latter two give names to buildings to recognize a distinguished individual or appreciation for a donation.

Originally issued in 1992, this policy has been revised five times, most recently in July 2020. Article four of this policy goes over the revision or removal process.

“Although generally discouraged, existing spaces and entities with honorific naming recognition may be renamed with the approval of the President’s Cabinet and the Board of Trustees,” the policy states. “If at any time the university determines that the continued naming of a space or entity may compromise the university’s integrity or reputation, the university may amend or remove the name.”

Before Ohio State developed its renaming request portal in 2021, naming requests were not processed officially, according to university spokesperson Chris Booker. Instead, individuals or groups made written or verbal requests, which were not maintained in any official process.

“If at any time the university determines that the continued naming of a space or entity may compromise the university’s integrity or reputation, the university may amend or remove the name.”

— Naming of University Spaces and Entities, Article Four

Other universities

The issue of naming buildings after people with reputations that contradict a university’s commitment is not unique to Ohio State.

As an undergraduate at the University of Richmond, Greer became involved in the Black student coalition to push for the change of two campus buildings that were named after a slave owner and a segregationist, the Rev. Robert Ryland and Douglas Southall Freeman, respectively.

“We sort of had an organic student movement among Black students who were advocating for those building names to be changed for greater academic accommodations for students,” Greer said.

Shira Greer is a master’s student in library science at UNC-Chapel Hill. As an undergraduate at the University of Richmond, she played an active role in advocating for the removal of a few building names.

Courtesy of Shira Greer

In 2022, about a year after an initial rejection to remove these names, Richmond officials decided to update their naming policy, resulting in the renaming of not just Ryland and Freeman Hall, but more.

“We were only initially advocating for the changes of two building names, and I believe when they actually did that, it was like six buildings,” Greer said.

At Yale, students also campaigned for the change of an undergraduate residency college, formerly known as Calhoun College.

Julia Adams, a professor of sociology and director of the college, said she not only played a role in this name change but she also noticed a positive change in the student body culture as a result.

Just like Richmond, the university initially announced in 2016 that the name would not change after students voiced their displeasure with Calhoun’s legacy and its misrepresentation of the university values.

“After the university had first announced that the name would stay, it had really already been culturally rejected by the students, and so that was a period in which we all, for quite a long time, kind of tried to handle that collectively as a community,” Adams said.

“After the university had first announced that the name would stay, it had really already been culturally rejected by the students, and so that was a period in which we all, for quite a long time, kind of tried to handle that collectively as a community.”

— Julie Adams, director of Yale undergraduate residency college

The name eventually changed a year later to the Grace Hopper College in honor of Yale alum Grace Murray Hopper, a computer scientist, mathematician and U.S. Navy rear admiral.

“I think what worked here, not just in the college but also with renaming, was leading with scholarship that is putting a serious thought and research into the decision,” Adams said. “Including scholarship about the individuals themselves, the character and the impact of names, how they function and all sorts of aspects. It keeps us all honest.”

“Including scholarship about the individuals themselves, the character and the impact of names, how they function and all sorts of aspects. It keeps us all honest.”

— Julie Adams, director of Yale undergraduate residency college

A look at Leslie H. Wexner

Leslie H. Wexner was given the name of The Ohio State University hospital in 2012, which is now known as the Wexner Medical Center. This philanthropist and billionaire has faced criticism for his association with convicted sex offender Jeffery Epstein, which has produced 524 signatures in a petition to remove his name from the university.

Credit: Molly Goheen | Managing Editor for Digital Content

Ferguson introduced resolution 54-R-42 in USG along with parliamentarian John Fuller in 2022, calling on the university to rename seven building names with legacies that contradict Ohio State’s values. The Wexner Medical Center was included in this resolution.

In 2022, USG passed a resolution urging the university to make its naming portal more publicly known to the student body and subsequently remove the names of individuals with “racist and other lascivious” characters from several campus buildings.

Credit: Ohio State Office of University Advancement

Philanthropist and billionaire Leslie H. Wexner was given the name of The Ohio State University hospital in 2012, which is now known as the Wexner Medical Center. The 1959 alum began his philanthropic connection three years after graduating with a donation of $5 million. According to the medical center, Wexner donated more than $200 million to the university within 30 years.

Wexner founded Limited Brands, or L Brands, in 1963 and was the owner of several retail chains including but not limited to Victoria’s Secret, Abercrombie & Fitch and Bath and Body Works. He also served on the board of trustees from 1988-1997 and 2005-2012 and was chairman of the board from 2009-2012.

Wexner had a close relationship with financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, who he gave control over his personal finances.

Epstein pleaded guilty to charges of procuring a child for the means of prostitution in 2008 and was arrested in 2019 on federal charges for the sex trafficking of minors in Florida and New York.

Wexner resigned from his position as the CEO of L Brands in February of 2020 allegedly due to brewing controversy.

Wexner’s representatives declined to comment publicly on his behalf, however, they point to statements made by attorneys who represent some of Epstein’s victims, who state it is highly likely Wexner was unaware of Epstein’s wrongdoings.

In addition to a 2023 USG resolution 54-R-42, 524 people signed a petition to remove Wexner’s name.

The legacy of William Oxley Thompson

The university library opened in 1913 and was renamed the Thompson Library in 1951 as an honorific naming to William Oxley Thompson, the fifth president of the university. Thompson also established de facto racially segregated schools in 1909, which had decades of lasting effects on the city of Columbus.

Credit: Molly Goheen | Managing Editor for Digital Content

Thompson was the fifth president of Ohio State from 1899-1925. He served concurrently as the president of the Columbus City Schools Board of Education for nine years. The university library opened in 1913 and was renamed the Thompson Library in 1951 as an honorific name.

Citizen Advocates for Public Education argued that Thompson instituted the university’s segregationist policies such as countermandering laws that gerrymandered neighborhood maps.

“Thompson was responsible for segregating Columbus public schools, which even those of us who worked there did not know that,” said James J. Bishop, a retired educational administrator and former director of the Young Scholars Program.

As a member of the Columbus City Schools Board of Education, Thompson established de facto racially segregated schools in Columbus, starting in 1909 and lasting until 1977. At Ohio State, he maintained racially segregated student housing during his presidential tenure.

Citizen Advocates for Public Education members said they sent their first letter to the Ohio State Board of Trustees in July 2020 and followed up with a letter to former university President Kristina M. Johnson in September of that year. The group was then directed by the university to submit an official renaming request using the online portal.

The evidence presented in the request included resources from “Getting Around Brown,” “Tigerland,” “Builders of Ohio, A Biographical History” and the 1979 U.S. Supreme Court case, Columbus Board of Education v. Penick.

“William Oxley Thompson was an avowed segregationist,” the request states. “Unlike many people who shared this view at the time in our history, he was in a position to help develop and implement policies and practices that were discriminatory and harmed generations of students.”

“William Oxley Thompson was an avowed segregationist. Unlike many people who shared this view at the time in our history, he was in a position to help develop and implement policies and practices that were discriminatory and harmed generations of students.”

— Renaming request submitted by Citizen Advocates for Public Education

The organization suggested Thompson Library be renamed after Robert M. Duncan, a federal district judge appointed by Richard Nixon and a graduate of the Ohio State College of Law.

Duncan was the first African American to serve on the Ohio Supreme Court and is credited for deciding the Columbus schools’ historic desegregation cases, according to the Supreme Court of Ohio.

“We thought it was much better to put in the hands of the Ohio State son who worked on the segregated Columbus schools and brought some sort of remedy that would address the longstanding problems of a segregated school district,” Bishop said.

Bishop said the university should still recognize Thompson’s contributions to the university by relocating his statue to where he made the greatest impact, like the Ohio Stadium.

“Part of education is about truth and how we perceive truth,” Bishop said. “In this day where we’re trying to scrub history out of the history books, we need to bring truth to their contribution for future generations.”

“Part of education is about truth and how we perceive truth,” Bishop said. “In this day where we’re trying to scrub history out of the history books, we need to bring truth to their contribution for future generations.”

— James J. Bishop, former director of Young Scholars Program

Bricker’s legacy

The building Bricker Hall was an honorific naming given to Ohio Attorney General John W. Bricker in 1983 for his long service to the university. USG passed its first resolution in 2021 to remove Bricker’s name because of the role he played in defending separate but equal facilities.

Credit: Molly Goheen | Managing Editor for Digital Content

Bricker served as Ohio attorney general from 1933-37 and governor of Ohio from 1933-45. He was a member of the Ohio State Board of Trustees from 1948-69, and the hall was named in honor of his long service to the university in 1983.

Bricker is also responsible for successfully defending the university position of separate but equal facilities for minority students in a case against Doris Weaver, a home economics student who took to the Supreme Court of Ohio to sue her denial of housing with her white counterparts, according to The Lantern.

He also adopted, along with U.S. Sen. Harry P. Cain, the Bricker-Cain amendment that prevented agencies from prohibiting segregation, according to USG resolution 54-R-42.

USG argued that having a university building named after Bricker is “incongruent with the university’s stated values of diversity and inclusion.”

The initiative also pointed to several other universities that successfully removed the names of historically racist figures from their buildings, which included UC Berkeley removing the name of John Boalt and Indiana University removing the name of Jordan Hall.

USG ultimately recommended Bricker Hall be renamed after Doris Weaver in recognition of her treatment as a Black student and her efforts for equality.

Though this resolution was passed in 2021, no further action took place. In the following two years, Ferguson drafted two similar resolutions, this time listing several other university building names.

“If we peeled back the layers deep enough, we would find that John W. Bricker was not the only unsavory figure that had a building named after him on campus,” Ferguson said.

Other building names challenged

Rutherford B. Hayes was given the building name Hayes Hall in 1891 by the board of trustees. The hall is the oldest remaining building on campus and houses the Department of Design.

Hayes served as the U.S. representative of the 2nd Congressional District of Ohio, 29th and 32nd governor of Ohio and the 19th president of the U.S. Through these roles, he played an integral role in the disbandment of the Reconstruction Era, such as the creation of the Jim Crow laws, according to resolution 54-R-42.

Abraham Lincoln, who is commonly known as the “great emancipator,” had Lincoln Tower, a coed residential dormitory, dedicated to him by the board of trustees in 1965.

While Lincoln enacted the Emancipation Proclamation, he also expressed that Black people were not entitled to equal rights and protection under the law, and freed an insignificant number of slaves.

He also stated in an 1858 debate that there “is a physical difference between the white and the Black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together … while they do remain together, there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any man am in favor having the superior position assigned to the white race.”

Justin Smith Morrill, a former Vermont senator, is considered to have been essential to the establishment of Ohio State and was granted an honorific dedication in 1965 that opened the coed residential dormitory of Morrill Tower as a companion tower to Lincoln in the autumn of 1966.

Morrill is also credited with introducing and writing the Land-Grant Agricultural and Mechanical College Act of 1862, which is commonly referred to as the Morrill Land Grant Act. This act led to the redistribution of more than 10.7 million acres of land seized from more than 250 indigenous tribes for the appointment of 52 postsecondary educational institutions.

While Lincoln enacted the Emancipation Proclamation, he also expressed that Black people were not entitled to equal rights and protection under the law, and freed an insignificant number of slaves.

Baker Hall was dedicated in memory of Newton Diehl Baker by the board of trustees in 1940 and became an all-male residence hall in September of that same year. In 1957, it was expanded into Baker Hall West and Baker Hall East.

Baker served as the mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, and then secretary of war under President Woodrow Wilson from 1932-37. He also served on the university board of trustees from 1932 until his death in 1937, according to the University Libraries.

Though he may be known for implementing the Selective Service Act of 1917, he also made it so that Black Americans registering would serve in segregated military units, according to USG resolution 54-R-42.

A part of Ohio State’s values, principles and behaviors is to act responsibly and be accountable. Some have argued the university has yet to fulfill this until its buildings and entities accurately represent the student body and its commitments.

Ferguson was committed to his mission to see the name of Bricker Hall changed before he graduated. Now, he fears no one cares about the legacy of building names at all.

“You have younger people that are coming in who are unaware of the work and the advocacy that others before them did related to this issue. Building renaming was one of the top issues that USG had in 2020 going into 2021,” Ferguson said. “Now, you don’t hear about it.”

As Citizen Advocates for Public Education members also continue to wait for answers, Bishop fears he won’t see any solutions in his lifetime.

“I think they’re playing a long game,” Bishop said. “I’m 87 years old.”

Words by Amani Bayo

Photo Illustration by Molly Goheen

Web Design by Gaurav Law