Leftover bombs hidden in the ground decades after World Wars I and II might be getting more explosive with time, research shows.

Because of their unique chemical makeup, bombs and other explosives remaining in the ground after the wars are becoming more volatile and, therefore, have an increased chance of exploding if disturbed, a new paper in the online journal Royal Society Open Science says.

The discovery came after researchers from the University of Stavanger's Department of Safety, Economics and Planning in Norway and the Norwegian Defense Research Establishment tested several bombs. They found that the "high explosives in the examined specimens were generally much more sensitive to impact than previously assumed," according to the paper.

Huge numbers of explosives were fired by both sides during both world wars, many of which never exploded and were embedded in the ground for over a century. Many of the explosives used in these wars contained chemicals known as amatols, which were mixtures of ammonium nitrate and TNT.

These amatols were used increasingly in World War I because of the limited supply of TNT at the time, because amatols were easy to make, and ammonium nitrate was readily available and much cheaper than TNT. They continued to be used in World War II until TNT was produced in much greater quantities toward the end of that conflict.

However, the researchers found that these amatols become more and more volatile with time because they slowly react with substances in the soil. This means that if they are disturbed, these old explosives are more likely to detonate and could endanger people.

"Earlier studies have revealed that the presence of moisture, when combined with certain other factors (i.e., certain metals), can cause chemical reactions, forming unstable compounds and sensitizing the amatol mixture," study author Geir Novik, a researcher with the University of Stavanger and the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment, told Newsweek.

"A contamination could occur during normal handling and mixing of the explosives, or they could come into contact with bare metal surfaces when loaded in ordnance or if the preventive lacquers within the ammunition deteriorate over time."

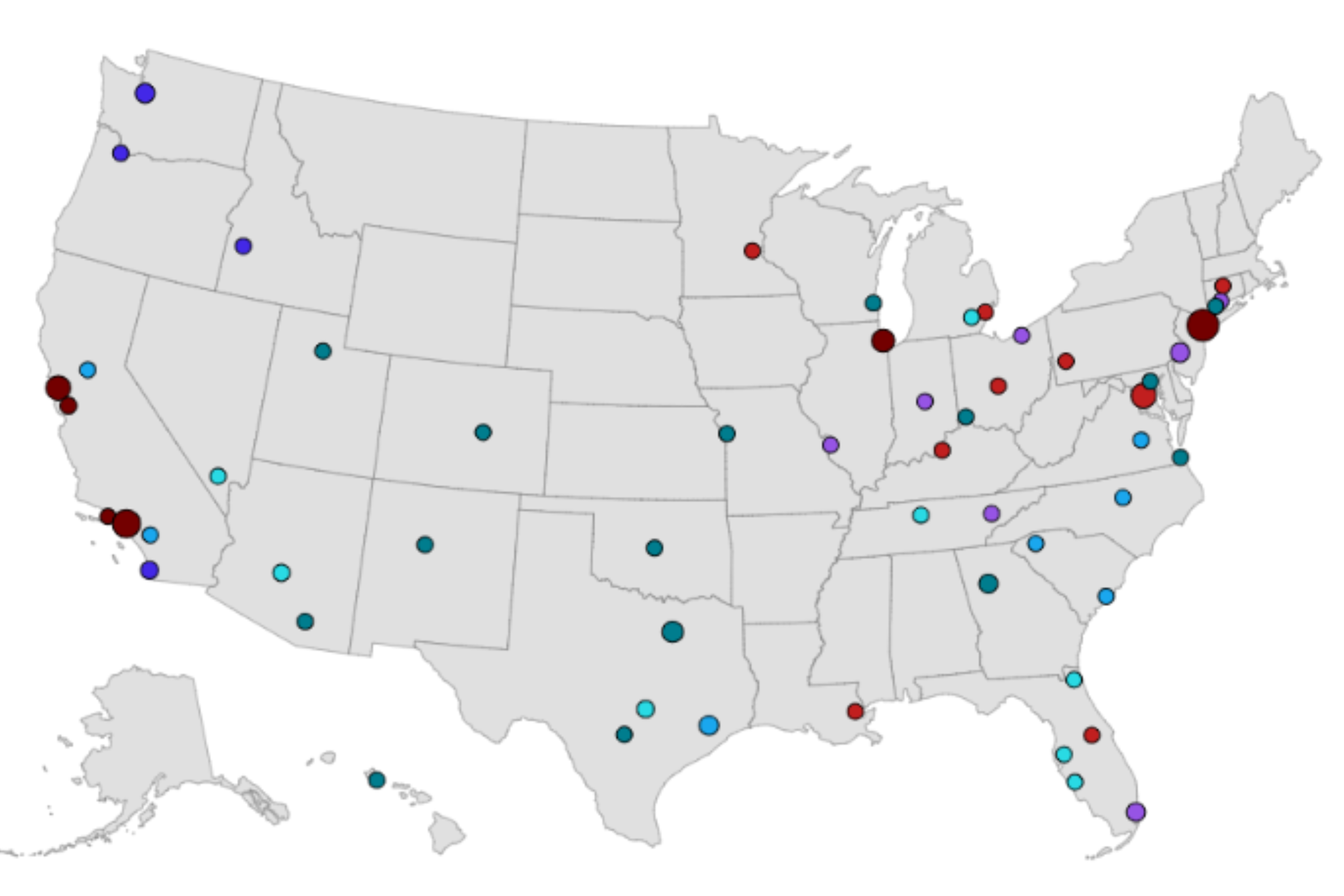

The researchers dropped heavy materials onto small samples of amatol collected from across Europe. They found that amatol bombs are more likely to explode from disturbances over time.

This could pose a major risk for people who stumble across unexploded bombs when building or digging, the authors said.

Explosives are found in backyards on occasion, such as earlier this year, when a 1,100-pound bomb was discovered in a yard in Plymouth, England. It was safely removed and detonated at sea. But in 2008, 17 people were injured after a bomb was detonated by an excavator working in Hattingen, Germany.

In addition, Amatol slowly leaches into the soil, poisoning the groundwater.

"The wide use of nitro organic-based energic chemicals, such as the aromatic TNT as found in amatol, in munitions has resulted in the contamination of terrestrial and aquatic systems," Novik said. "Several studies describe the toxic and carcinogenic effects of these explosives and their degradation products to various terrestrial, aquatic and avian receptors. As munition casings continue to deteriorate, we expect an increase in the release of their harmful constituents in the future."

The authors said these findings are crucial to consider when construction is done in places once involved in battles, as this could lead to explosions and risks to human life.

"The study will have a substantial impact on how ERW-related risks are assessed, and sets in place new boundaries for safe and practically feasible disposal techniques," Novik said. "In the aftermath of war and armed conflict, millions of tonnes of ERW and unexploded ordnance have been left on the battlefield or dumped in landfills, lakes and seas. In the current Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, for example, it is estimated that the number of UXO could be increasing by well over one million pieces each passing year."

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about explosives? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Update 4/3/24, 12:38 p.m. ET: This article was updated with comment from Geir Novik.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.