Why Is It So Hard to Get a Doctor’s Appointment in Philadelphia?

If Philly is one of the greatest medical cities in America, why does it take so long to get a doctor’s appointment here — and does it have to be this way?

Why has getting a doctor’s appointment become a waiting game? / Photo-illustration by C.J. Burton

I’m sitting in an armchair in a brightly lit room, my hands gripping my knees, head bowed as if I’m deep in prayer, when I feel the first needle pierce the back of my scalp. One sharp prick. My eyes water.

Then comes number two. A familiar relief washes over me as I feel the sting of the third shot, then the fourth. The doctor presses a small square of gauze to the area, pats away tiny dots of blood, then fluffs through my hair to repeat the process in another spot.

These quick little jabs to the back of my head deliver doses of cortisone to treat an autoimmune condition called alopecia areata. It causes me to sporadically develop bald spots the size and shape of coins — from dimes to half-dollars — on my scalp. The condition enjoyed a moment in the spotlight a few years ago when it was revealed to be the catalyst behind Jada Pinkett’s shaved head, which was the catalyst behind the Chris Rock joke at the Oscars that was the catalyst behind the infamous Will Smith slap.

Despite the prestige, I mostly associate my ailment with stress — not cancer stress or even torn-rotator-cuff stress, but stress in the sense that I’m vain and the bald spots can grow, and I don’t have Jada’s Hollywood bone structure. So when I notice a new dime or quarter on my head, I simmer in self-conscious helplessness until I can get in to see a dermatologist for the shots. When I’m lucky, it’s a short wait — a few weeks, maybe even days. When I’m unlucky, it can be a month or more — eons in simmering time. Once, some years back, the scheduler told me they were booked out for six months, at which point, she offered, I could try again. Or look elsewhere.

I was incredulous, then perplexed. I’d already left my last dermatologist because of exceedingly long waits for appointments. And anyway, I wondered at the time, what the hell is even happening here? This was Jefferson Med — a behemoth! My appointments rarely exceed 10 minutes. I’m punctual. I’d birthed two babies in their hospital, even courteously scheduling one of them. Couldn’t we work something out?

Eventually we did, in that I called every day until I finally snagged someone’s cancellation. And once there? The doc told me I could message him in the portal when I needed to be seen and he’d squeeze me in himself. The offer felt like a winning lottery ticket, and I cashed in a couple times, gratefully. But this past fall, I got a Dear Patient letter — he was moving out of state. I’d have to start fresh with a new doctor, hopefully working my way into a new portal, a new safety net.

And so there I find myself one frigid day last January, relating all of this semi-sheepishly to the new doc between jabs: “I mean, I know it’s not life or death or a torn rotator cuff. … ” But she’s a sympathetic audience: Roughly half of her patients have mentioned waiting to her, she tells me. And she has a story of her own, about a time her father — not a Jeff patient — noticed a lesion on his head and called for a dermatology appointment. Six months, they told him. He took it.

Later on, he happened to mention this to his daughter, who was at that point still a medical student but knew enough to tell her dad to call back, giving him specific language to use — magic words I no longer remember. (Bleeding? Growing?) Tell them there was suspected malignancy, she directed. That word I do remember: malignant. Which, it turned out, it was.

The callback got him the appointment, and he was promptly diagnosed with a particularly aggressive form of cancer. Today, after chemo and radiation, he’s doing fine, my dermatologist tells me — but, she adds, dabbing the last droplets of blood from my scalp, his own doctor told him that had he waited that six months, it would have been too late.

By now, most of us understand that access to care is one of the many issues that plague America’s beleaguered health-care system. But there’s been a sense, I think — at least among those of us in the habit of absorbing the daily headlines — that the problems have mostly revolved around certain specific, desperate contexts. The medical deserts plaguing rural America, for instance. Niche specialists facing exceptional bursts of demand, like child psychiatrists since COVID. And the increasing number of patients in our country — the poor, the undocumented, those seeking reproductive or gender care — at the mercy of merciless legislative crusades.

What’s becoming more and more apparent, though, is how much more widespread, even mundane, the issue of getting to your doctor — or a doctor — really is, particularly when it comes to primary and preventative care. You know, the kind of care that keeps chronic conditions in check and keeps you out of the more expensive, overcrowded ER and also just generally helps keep you up to snuff and/or alive.

When I say widespread: Anecdotally, everyone I know — and probably you, too — has a story about waiting. A friend of mine who called for a physical with her Jefferson-based primary-care doctor in October couldn’t be seen until February. Another got a quote for a year-and-a-half waitlist to see a Penn Med gynecologist for an annual exam. When she looked instead to private practice, she took the best they could offer: a telehealth visit in two months. Still another friend who had an iffy mammogram at Penn was told she’d need to wait a stomach-churning month before she could even call to make an appointment for a biopsy.

Meantime, a Main Line Health patient I know needed a sick appointment, but her doctor had left the practice and they were booked out three months for “new patients.” When her asthma flares up, she says, her MLH pulmonologist appointments are regularly three to six months out. One of my neighbors waited upwards of four months last year for a run-of-the-mill pediatric allergy appointment at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), while another sought an appointment with a CHOP autism specialist and was told there were none, and no waitlist, no cancellations. “Please don’t call back,” the scheduler said.

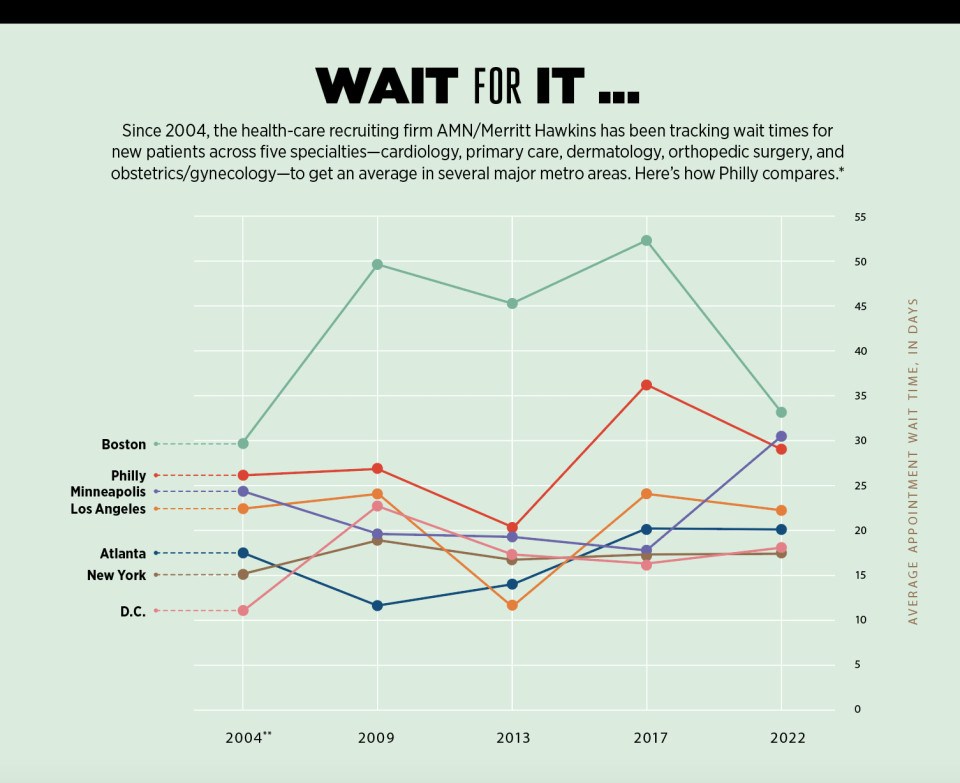

It bears mentioning that all these people are insured, English-speaking, internet-literate city dwellers who have some flexibility within their schedules. It’s hard to imagine getting to see a doctor is easier or more expedient for anyone else. Last May, the Inquirer ran a piece about the sole low-cost, city-run primary-care clinic in the Northeast — a place at which 40 percent of patients lack insurance or the money to pay a typical medical bill. Many are immigrants. Patients there might wait up to a year to see a doctor, squeezing into cubicles for exams. Still, like so many frogs in so many pots, it’s been easy for us collectively to miss the extent of the trend here — at least, until a 2022 survey from health-care recruiting company AMN/Merritt Hawkins put numbers to it. Across five different specialties, the average wait times for new patients in 15 of the country’s largest metropolitan areas, Philly among them, were as long as they’ve been since the company started tracking them 20 years ago — up 24 percent, to an average of 26 days.

Here in Philadelphia — a city that trains one of every six doctors in America, in a metro area with one of the highest per capita rates of health-care workers in the country — the average wait to see a cardiologist was 39 days (up from 28 in 2017, which was up from six in 2013), 34 days for a family-care practitioner (up from 17 days in 2017), and 59 days for an ob-gyn (up from 51 days).

Why, though? The question that nagged at me years back with the dermatologist has only intensified as everything else in the world seems to be getting faster, more geared to our on-demand economy. Why — especially in this eds-and-meds city — can it take such a maddeningly long time to see a doctor? And in a health-care system teetering on the backs of already-overburdened providers, is there anything anyone can do about it?

“When I was a kid,” says Elaine Gallagher, a brisk 50-something senior vice president at CHOP, “I didn’t know anyone who had a food allergy. Right?”

I think back to my own childhood, in the 1980s. I knew a couple kids who were allergic to peanuts or chocolate — but only a couple. I know a whole lot more now, which is the point Gallagher is making. She leads CHOP’s six specialty practices, the hubs for its pediatric specialists — including the food allergy program, now one of the most in-demand appointments in the system, with new-patient waits that frequently exceed a year.

“I’ve worked here for over 30 years,” she says. “And for over 30 years, we’ve been talking about access. It’s just a very difficult problem.” Part of the inherent difficulty, she explains, is the way demand has evolved nationally over the years, and how certain conditions have exploded — conditions that require follow-ups, specialists, time. Like food allergies diagnosed in children, which the CDC says have grown by 50 percent since the 1990s.

Also up? Developmental disabilities. Type 2 diabetes. Anxiety. Depression. All of this is according to a 2023 study from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM), which also showed that between 2017 and 2020, obesity affected almost 20 percent of our children, up from about 14 percent two decades earlier. (One pediatrician I talked to noted that half the kids she saw that day had childhood obesity, which can bring with it conditions — sleep apnea, disrupted menstrual cycles, elevated cholesterol, etc. — that require closer tracking … and thus more follow-up appointments.)

Meantime, not only has the number of pediatric doctors not kept pace with the ballooning need, but a catch-up feels utterly out of reach, given current trends. Fewer medical-school graduates are choosing to go into pediatrics, Gallagher says — some 600 fewer from 2019 to 2023, to be exact. This year, 13 of the 15 accredited pediatric sub-specialty training programs saw fewer applicants nationally than in previous years, Gallagher adds, and couldn’t even fill all their slots.

But wait! It gets worse. Much of medicine is facing a similar plight: On one side, there’s seemingly endless demand — we’re a growing population and an aging population, and people over 65 go to the doctor at least twice as much as younger people. Six in 10 of us have a chronic condition. And the Affordable Care Act gave more of us the financial means to actually see a doctor. On the other side, supply isn’t growing fast enough to keep up with demand, and not enough doctors are going into the areas where we need them the most.

This is particularly and painfully true when it comes to primary care. In Philly, there’s just one PCP for every 1,243 of us — and that’s actually slightly better than the national average. As a nation, we’re also staring down shortages of neurologists, ob-gyns, pulmonologists, psychiatrists, cardiologists, optometrists, urologists, and critical-care specialists.

At this point, you must be wondering why in God’s name we’re short on all of these doctors when being a doctor in America is still a relatively well-paying, noble, mom-pleasing profession. The answer, like everything else in modern health care, is complicated.

A CliffsNotes explanation might well begin with COVID, which spurred some 145,000 burned-out practitioners to leave the field. (Half were doctors; a quarter were nurse practitioners.) This has been, to put it mildly, a major gut punch to the system — but it was hardly the first blow. A full decade before the pandemic, nurses and doctors were reporting high levels of burnout relative to the general population — too many patients in a day, too much bureaucracy, too much wrangling with insurance, too much work in off-hours.

The burnout and resulting labor shortages have exacerbated the situation for those who remain, notes Christian Terwiesch, a Wharton and Perelman School of Medicine professor who studies operations, innovations and policy in health care — creating “a huge problem that over the last 10 or 15 years has bubbled up to be one of the top three challenges every health-care system struggles with.”

Consider the age of our current medical workforce: Some 30 percent of working docs are 60 or older right now, on the cusp of retirement.”

Another factor is that even as demand has expanded, there’s been no significant expansion in funding for training new doctors. Not for lack of interest from would-be practitioners (hey, did you know medical-school applications shot up during COVID?), but because internships and residencies are largely funded by the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Since 1997, that funding has only expanded to support some 1,200 more residencies. That’s not enough. Especially given the age of our current medical workforce: Some 30 percent of working docs are 60 or older right now, on the cusp of retirement.

Then there’s the paltry rate at which Medicare reimburses doctors for their services — a rate that’s decreased 26 percent since 2001, despite inflation. That means physicians are providing the same services as always but for less money, and spending more to do it. This, the AMA notes, has led more doctors to drop patients who rely on Medicare or Medicaid. This often means — here we are again — longer waits and more hoops to jump for those patients, who scramble to find care elsewhere.

Another whammy: Doctors practicing certain types of medicine — pediatrics, endocrinology, family and internal medicines, for example — make less money than many specialists. This has a little to do with how much training and insurance is required to practice in their areas, but far more to do with the rates at which insurance (both private and Medicare) reimburses their services. Broadly speaking, procedures big and small are valued at higher rates than more preventative, prescriptive, diagnostic general care, and the take-home pay reflects this.

Now, it’s true that your average family practitioner or pediatrician does better than most of us, financially speaking — their median salaries are $255K and $251K, respectively. But it’s also true that plastic surgeons do way better ($619K a year on average). So do cardiologists ($507K) and orthopedic surgeons ($573K). Tack on to that student debt — on average, doctors graduate owing roughly $250K. Even the most altruistic helper-types aren’t totally immune to that math.

So: Swirl the laws of economics together with all these factors over a couple decades, and here we are. The Association of American Medical Colleges predicts a national deficit of up to 124,000 physicians by 2034, but there’s no need to look even that far ahead. “The physician-shortage crisis is here,” American Medical Association president Jesse Ehrenfeld announced last November. “And it’s about to get worse.”

There are variations as to what this crisis (and worse) can look like. As Ehrenfeld noted, there are already swaths of pregnant women in some states who can’t find an ob-gyn; countless Americans have no easy access to specialists. By comparison, Philly boasts an embarrassment of riches — unevenly distributed, yes, but riches nonetheless. Still, nobody is immune to the effects of the shortage.

“We’re constantly recruiting,” says Adam Edelson, who runs ambulatory operations as a VP for Main Line Health, a 13,000-employee mega-system. (He’s not alone: I hear this from executives at Penn Med, Jefferson and CHOP as well.) Top-notch doctors, advanced-care providers — every system wants more of them, Edelson says, which is an ongoing challenge. (Not to pile on here, but there’s a shortage of support staff, nurses and midwives, too.) And his is a high-quality urban/suburban health system ranked in 2023 as one of the best employers in the state, with competitive pay and benefits. “I can only imagine what other organizations may face,” he says.

CHOP’s neurology department offers another window into the morass. At 70 neurologists deep, it’s bigger than many entire pediatric practices, Elaine Gallagher points out: “And we still can’t meet the demand.” Any attrition at nearby neurology departments means more patients land at CHOP — which is what’s happened, to the tune of 1,500 more kids over the past two years. And yes, hiring more neurologists would help, she adds — “but there just aren’t a great number of them out there waiting to be recruited.”

Even CHOP can’t get blood from a stone.

But if there’s any good news here, it’s this: We know how to fix this issue. (And by “we,” I mean the AMA, NASEM, medical economists, regular economists.) We know, for instance, that better Medicare reimbursements are crucial. As is tamping down some of the time-sucking, demoralizing red tape insurers put health-care workers through. Also: better loan repayment plans, debt forgiveness, and (yes!) tuition-free education, to sweeten the deal for doctors; easier pathways for foreign-trained physicians to practice here; money to expand residency training programs. Many of these solutions are already in actual pieces of legislation floating around right now.

But therein lies the rub: The task of caulking the sizable gaps in the medi-verse essentially falls to the only system more beleaguered, teetering and glacially slow than health care — the American government.

In the meantime, how would you feel about a group physical? Or AI listening in on your next doctor’s appointment? Or an asynchronous appointment where you’re treated but never actually see a doc?

These are just a few of the ways health care is evolving to deliver care to the people who need it. Tackling delivery is the best way forward, Wharton’s Terwiesch says, in large part because the high demand will never go away, no matter what happens on the supply side. It’s just the nature of health care: If it’s done well, people live longer and consume still more — “like we’re running a race on a treadmill that gets faster than we can ever run.”

Improving care delivery, he says, might just begin with reframing the mission. “We believe that if we keep researching and working, we’re going to find the one thing, the silver bullet that cures the health-care delivery problem we have in this country.” Having recently immersed myself in the canon of health-care troubleshooting, I understand what he means: Could the answer be team-based care? Value-based care? A single-payer system! And so forth.

Instead, Terwiesch says, “I think we’re better off saying, ‘Look, health care is a very complex thing.’” Or — he corrects himself — a mass of interconnected things. And in this mass, “It’s thousands and thousands of little problems plaguing the system. So let’s just acknowledge them, and get to work, and every day, with these thousands of problems, just try to fix one at a time.”

Enter Roy Rosin, the affable, animated chief innovation officer for Penn Med, who has spent a great deal of time over the past decade aiming to fix one problem at a time, particularly the ones that relate to getting more people more care faster. When I called him one day last winter, he rattled off so many different Penn pilots and new protocols — a.k.a. “The Portfolio” — with such enthusiasm and encyclopedic breadth that I could barely keep pace typing.

There are too many to name here, but among some of the more fascinating Portfolio highlights, at least from this layman’s perspective, are these:

- A custom-designed software system that finds unused rooms and spaces in the labyrinthine Penn system where patients can be seen and doctors can work — literally making the best use of its real estate resources.

- A project being run by a sleep neurologist that helps determine for doctors at what point it becomes more efficient to bring a patient in for a visit than to communicate over the portal.

- An asynchronous model — this one in dermatology — that allows a patient to send in photos and information via a portal. The doctor later reviews the treatment plans sans visit, thus hopefully allowing doctors to see more patients, catch skin cancer faster, and get more people with minor problems into treatment “at higher and faster rates.”

Rosin gets really jazzed by the work of “reimagining care models.” One of his favorite examples, among many, is what Penn Med did with breast reconstruction surgery for cancer patients some years back. Because Penn’s a global leader in this arena, there’s always high demand, which has translated to long waits. Part of the issue, Rosin says, was the intensity of the 90-day post-op care schedule — five separate clinical visits for stuff like drain and pain management and checks for motion, infection and scars.

“There was no waste in those visits,” Rosin says — every piece of care was necessary. But, the innovation team wondered, could a Penn home-care team manage drain care and removal? Might some of the motion and pain assessment be done via a portal? Could the surgical site be assessed at home, with photos? When they tried these things, they realized that a 30-minute in-person visit could essentially be reduced to a five-minute phone call, Rosin says, eliminating 50 to 60 percent of in-person follow-up needs. This allowed new breast-cancer patients to get in more quickly without changing outcomes for current patients. And — a bonus — it saved people recovering from surgery a whole lot of schlepping.

You can see why Rosin gets excited about ideas like this. You can also see why so many organizations in Philly’s health-care ecosystem are putting money and talent into exploring and making similar changes. Everywhere around Philly, providers are experimenting with such innovations, from the granular (like those automated text reminders with “cancel” options that cut down on wasteful no-shows) to the massive (see: the telemedicine revolution).

Speaking of telemedicine, some fixes are so widespread that they are now — or soon will be — de rigueur, like online self-scheduling, and the automated “fast passes” that offer patients already in the books earlier appointments when cancellations occur. (This works! Jefferson Health, for one, reports moving up some 4,000 appointments a month by an average of 30 days.) Some fixes involve rethinking who should do what, like the now common practice of having nurse practitioners and physician assistants offer care, or like a CHOP pilot exploring how primary-care doctors can successfully manage certain conditions — headaches, maybe, or constipation — without needing to refer patients to a specialist. Nemours is looking at ways to embed specialties into primary-care outposts to make it easier to access things like preventative cardiology and autism evaluations; it’s also setting up school-based health centers.

Some other solutions seem absolutely wild at first blush, like sharing appointments with other patients who have the same or similar needs. (Maybe not so wild: A National Institutes of Health paper a decade ago found that patients in a shared-appointment model were more satisfied than those receiving ordinary care.) And some proposed fixes are still a bit … unsettling, like AI “listening” in on appointments, ostensibly to help docs with note transcription, summary generation, prescription ordering, and other time-saving efficiencies. “We have a number of AI initiatives on how we might reduce the time physicians spend with the medical record,” Elaine Gallagher says. “Those are in really early stages.”

Medical providers seem to hover between measured curiosity and circumspection when it comes to AI. But the technology will surely continue to speed ahead.”

The providers — at least, the ones I’ve spoken to — seem to hover, as Gallagher does, between measured curiosity and circumspection when it comes to AI. But the technology will surely speed ahead. Last year, one Axios story pointed to the multiple AI tools already “interacting” with patients by listening for signals or voice indicators of self-harm and clinical depression, based on clips of people talking to their doctors.

Of course, the reporter noted, there are some obvious issues here — namely, “a number of privacy concerns as well as worries about accuracy of the data and potential biases.” Which reminds me of something Terwiesch says about trying to move the needle, problem by problem: “It’s a lot of work, and it will keep us busy for a very long time.”

But then there’s this: I can always get in to see Alexis Lieberman. In the 10-plus years I’ve been taking my kids to see their pediatrician, I can’t remember a time I struggled for an appointment. This isn’t because Lieberman isn’t busy; she runs a private practice affiliated with a large regional physician group, and between two offices, she has five providers, nine support staff and 3,000 patients.

Over the years, I’ve awakened her in the middle of the night in a croup-induced panic (twice). I’ve texted photos of rashes and random medical mysteries in off-hours, earnestly messaged her about how to cook my baby’s first bite of egg (“Well, how do you like your eggs?” she answered an hour later), and just generally relied on her for everything from easing coughs to delivering discipline. In my neighborhood-parent circles, this sort of doctoring has made her very popular.

So why, I ask her, can I always snag an appointment at her office with none of the Sturm und Drang that exists elsewhere?

“Because,” she says matter-of-factly, “I made a decision that I want you to be able to.” (Have I mentioned that I love her?)

Lieberman goes on to explain that this decision has really entailed a series of choices. Like, for instance, the choice to open the office’s schedule just two weeks in advance, which, she allows, was scary at first: You lose the financial security of knowing that for months at a time, patients will be steadily pouring in, one after the other. But it also means the books are never too full for people to get a timely appointment. She reserves a certain number of sick slots every day; beyond that, as issues come up or appointments are needed, patients can see if there are slots open and, if not, wait at most two weeks to jump back in and grab an opening.

She’s also chosen, she says, “to do today’s work today.” That means filling out everyone’s school forms that day, no waiting. And if she hasn’t held back enough “sick time,” she stays late to see patients in need. In short: “I work harder on a day when there’s too much work and less hard on a day when there’s less work.”

That she has choice in these sorts of decisions and others — including the one to grow her practice over the years as demand has climbed — is in part a function of the relative autonomy that comes with private practice and in part a function of scale. The fewer dominos you have, the fewer can fall, and the less time it takes to right them, you know?

This is something that Alexander Vaccaro, president of the private Rothman Orthopaedic Institute, talks about. “I have 238 orthopedic surgeons and a staff of 2,200,” he says — compared to tens of thousands at larger systems — “so I have the ability to quickly pivot.” At Rothman, “pivoting” has meant tweaking the model to allow for same-day and weekend appointments, plus opening walk-in clinics in addition to urgent-care facilities.

The private model has different drivers when it comes to access, Vaccaro says: “I have to make you happy, because if I don’t make you happy, you go elsewhere. And then I go away tomorrow. But if you’re at an institution, that institution is not going away tomorrow.”

This is not to dump on the institutions, which perform plenty of services that private practices can’t and serve as cornerstones of the regional economy. (Also, please note where all that research and innovation is coming from.) But private practices have an edge of their own in the medical ecosystem: One 2018 Merritt Hawkins survey showed independent physicians seeing 12 percent more patients on average than employed physicians.

Herein lies yet another problem contributing to long waits: Thanks to the many economic pressures on medicine (including the havoc COVID wreaked), the number of private practices in the U.S. is shrinking. Doctors employed by a hospital or corporate entity shot up from 62 percent to 70 percent between 2019 and 2021. “Is the End of Private Practice Nigh?” Forbes pondered a couple years back.

One would hope not — aside from that being a bummer, more options are obviously better for patients. As Lieberman posits to me: “Does a shortage mean that every practice is full? Or is it just that certain popular practices are full?” With this in mind, I recently checked how soon I could get in for a physical with my own PCP: four months. Then I called, somewhat randomly, the Ala Stanford Center for Health Equity in North Philly — semi-expecting a longer wait, since it’s known for taking patients whether they pay or not, which you would think might make it hard to get an appointment. They could fit me in within the month, the scheduler said. Huh.

There’s good news to be found elsewhere, too — including in the Merritt Hawkins survey that revealed the troubling trend of longer appointment waits. There were two exceptions. One was orthopedic surgery, which held steady at a mere 10 days. The other? Dermatology. In 2017, the average wait for a derm appointment was 78 days. In 2022, it was nine days.

Nine!

This tracks, actually, with my last dermatologist appointment, back in January. I’d gotten in within a week and a half. At the time, I thought it was sheer luck. Now I see what it actually was: a series of small fixes (and maybe also some luck). In the past handful of years, Jefferson reports having boosted its number of telehealth follow-ups, which opened up more in-person appointments. It has expanded hours and streamlined waitlist and scheduling processes, including offering 10-day open-access slots, similar to Lieberman’s model.

The prospect of thinking about our access problem this way — fix by fix — is equal parts exhausting and reassuring. Exhausting because of those thousands and thousands of problems, plus the Sisyphean demand. Reassuring because it’s better than throwing up our hands, and because, as we’ve seen, sometimes things actually do work, and people get the care they need. Just ask Elaine Gallagher. Over her 30 years at CHOP, she says, “I can see that we’ve made a difference. We’ve increased the number of patients we’re seeing.” That’s not everyone’s lived experience, she knows. Also: How much care could ever be enough in this world? And yet, she says, “We are making some dents.”

Published as “The Waiting Game” in the May 2024 issue of Philadelphia magazine.