Brazilian curator Adriano Pedrosa proposed the title for the 60th Edition of La Biennale di Venezia. ‘Foreigners Everywhere’. “The expression has many meanings,” Pedrosa said. “One could say that wherever you go, wherever you are (and especially in Venice), you are always surrounded by foreigners… And then in a more personal, perhaps psychoanalytic subjective dimension, wherever you go, you are also a foreigner, deep down inside.” As artistic director of the Sao Paulo Museum of Art, his signature installation technique – taking old paintings off museum walls and floating mounting them in giant panes of glass set into concrete plinths – transformed how we relate to the history of art.

Painfully apt for a city swarming with a locus of foreigners, Pedrosa is only this exhibition’s fourth ‘foreign’ curator in its history. The title, a somewhat sober contrapposto to Cecelia Alemani’s surreal 2022 title ‘The Milk of Dreams’, keys into the global phenomena of mass migration whilst simultaneously triggering a self-awareness of contributing to the swarm. Why are we so enchanted with this city, and why is it so precariously at the forefront of our minds in the context of art? Countless writers and artists have tried to answer this question, perhaps most famously Anthony Burgess. “Despair of man and go to Venice: you will cease to despair. If human beings can build a city like this, their souls deserve to be saved.” (1988). Indeed, if art was honey, this place – built entirely by humans on top of a petrified forest – is a giant honeycomb, deliciously full of opportunities to see, taste and inhale the production of some of the finest things humans are capable of. Here is a roundup of just some of the wonders we were able to see:

Perhaps the most exuberant, celebratory, and uplifting of the Giardini pavilions at this year’s Venice Biennial was by Jeffrey Gibson – a member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and Cherokee descent, at the American Pavilion.

Born in 1972, Gibson grew up in major urban centres in the United States, Germany, and Korea. Being from everywhere and nowhere, Gibson would deploy these myriad influences as a form of resistance in his art – hence his show’s title ‘The Space in Which to Place Me’.His practice unravels how stereotypes of Indigenous people are used to delegitimise cultural expressions that exist outside the mainstream. This stuck powerful cultural chords across numerous minority groups. Awarded honorary doctorates from Claremont Graduate University (2016) and the Institute of American Indian Arts (2023), he is an artist-in-residence at Bard College.

First introduced to his work by Carrie Scott ahead of his solo with the Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, I was sorry not to have seen him in 2023 at the Aspen Art Museum (The Spirits Are Laughing). However, this was well worth the wait. Gibson’s vibrant works – garments, sculpture, performance, video and painting – blend Indigenous aesthetic histories with the hard edge of Modernism. Through this expansive repertoire, Gibson questions the complex, shifting narratives of selfhood and what it means to be several things in a multicultural society that still upholds stereotypes. At the opening, he said, “…we have to stop using the word minority – as it denies the human experience of being with your people in your world – and the feeling of being centre of that – no matter how few of you there are.”

Jeffrey Gibson’s selection to represent the United States at the 60th Venice Biennale marks the first solo presentation of an Indigenous artist for the U.S. Pavilion. ‘The Space in Which to Place Me’ is commissioned by Kathleen Ash-Milby (Curator of Native American Art, Portland Art Museum), Louis Grachos (Phillips Executive Director, SITE Santa Fe), and Abigail Winograd (Independent Curator) and is presented jointly by the Portland Art Museum and SITE Santa Fe.

My happiest moment was slipping into the French pavilion ahead of the crowds, just before it opened to see ‘Attila cataracte ta source aux pieds des pitons verts finira dans la grande mer gouffre bleu nous nous noyâmes dans les larmes marées de la lune, matoutou falaise’, (2024), by the inimitable Julien Creuzet. Curated by Céline Kopp and Cindy Sissokho and commissioned by the Institut Français, this title translates into a cacophony of sounds – Attila cataract your source at the feet of the green peaks will end up in the great sea blue abyss we drowned in the tidal tears of the moon – with reason. The text in this show and his phenomenal catalogue calls for refusing to give away our interpretative freedom.

Including a series of previously unpublished works and extracts from literary texts (poems, fiction, science fiction, critical essays, and a film script), Creuzet reveals common imaginaries shared among the African diasporas. Somehow, in this mele, he gives us access to the otherwise elusive and often unrecognisable. Five researchers he invited proposed titles: Ari Lima, Noémi Michel, Mukashyaka Nsengimana, Sofía Bonilla Otoya, and Maboula Soumahoro. Their voices and collaboration were fundamental in bringing together the sea-related stories and imaginaries that form the show, reflecting Creuzet’s Martinique roots. In this, he references influential members of the Negritude movement – Glissant, Aime Cesaire and Suzanne Cesaire – who understood that the quest for decolonisation was not a quest for the sovereignty of single nation-states but a restructuring of the world itself.

‘The sight of the matatu Falaise (the Antilles pink toe tarantula) is a gift when it appears in dense forests, on the bark of the Zamana trees or the rocks of the Martinique shores. It requires a deep connection to the environment, an eye that sweeps the contours and glides over the textures. It is about appearances and disappearances, what is given, protected, and unseen…’

This tarantula, endemic to Martinique, is Creuzet’s leitmotif. Thinking on this, we enter a heightened awareness as we trip through his hallucinogenic installation at the French Pavilion, swaying his soundtrack of Afro-Island-Acid-House beats. Creuzet is giving us access to a deeper connection to the many ecologies of life; I don’t understand any of it, but I can feel it, and it is utterly magical.

What an honour to meet the superstar curator Azu Nwagbogu and legendary scenographer Frank Houndégla in person at the official inauguration of the Benin Pavilion with Tate Curator Osei Bonsu. For the first time in its history, Benin is participating in the Venice Biennale, now in its 60th edition, and they nearly stole the show! Nwagbogu and his curatorial team – curator Yassine Lassissi and Houndégla – selected four significant artists: Chloé Quenum, Moufouli Bello, Ishola Akpo, and Romuald Hazoumè.

Under the title “Everything Precious Is Fragile”, the exhibition showcases the rich and illuminating ways artists have responded to Benin’s complex, often elusive history – in particular, the figure of the Amazon as matriarch and Vodun spirituality. It also delves into the contemporary realm with the Gèlèdé philosophy, focusing on “rematriation”, a feminist interpretation of restitution that advocates the return of objects and Beninese philosophy and ideals predating the colonial era.

Spotlight on the wall is the curatorial statement that states, “Activists of all convictions in their sincere efforts to enforce emotional truths often lead to polarisation and absurdity. Our overwhelming influx of (mis)information fails to foster genuine understanding. Emotional truths require subtlety and allure. Amidst the clamour for decolonisation through activism, these artists seek to inspire through beautiful nuance.” Such a kind, generous and profoundly inclusive gesture invites us all to collaborate in a better future. As José Pliya, the commissioner of the Benin Pavilion, states, “Benin will then be, in the words of Léopold Sédar Senghor, at the great ‘rendezvous of giving and receiving’.”

Often, the choice of a new medium can transform how we think and, in turn, how we build pictures (or cities) or make sense of the world. It was the mosaic for Romanian artist Șerban Savu, representing his country in Venice. “Now I think in small moments, building up an image – as if with tiles – never certain of the total picture,” he said at the opening of What Work Is. An exhibition centred around the history and relationship of work and leisure, curated by the artist Ciprian Mureșan (showing next week at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, London), it addresses the general theme ‘Foreigners Everywhere’.

Inside the Pavilion, arranged in a vast polyptych, about forty paintings—a cross-section of Savu’s work over the last fifteen years— portray characters, like NPCs, caught in the lull between work and rest. A tableau that captures random, intimate moments of inactivity or elan; because it is also a giant mosaic – paintings set into a cement-coloured wall – there is a sense that we are looking at individual tiles/ pixels. A reflection on the displacement/ loneliness associated with migratory work is also an enquiry into the often-hidden characters who shape our urban spaces. Substrates, like subtexts, matter.

Across from the polyptych, a large bench incorporates plinths displaying architectural models adorned with mosaics. Unlike the labour-focused narratives typical of Socialist mosaic art, which portray grand achievements, the mosaics convey what happens between the main events. Where are the icons now? They seem to ask. What pictures are we building, and more importantly, how are modern materials shaping our minds? Invited to respond to Savu’s project, the Brussels-based graphic design studio @_atelierbrenda (Sophie Keij and Nana Esi) used cement to write onto the building’s façade – almost an invitation for someone to come and place their tiles of thought… the exhibition continues at The New Gallery of the Romanian Institute of Culture and Humanistic Research in Venice.

If you ask me why I do this, why I keep going back to the giant honeycomb that is Venice – aside from its very existence, restores your faith in humanity – is this: the complete, unmediated, unpredictable joy of an encounter with actual creative genius. Enter Wael Shawky – think Monty Python meets a post-colonial musical produced by South Park. By incorporating a musical theatre score’s simple, entertaining device but flipping on a lyrical Egyptian tip, he gives us the soundtrack to his thesis: history is a record of subjectively depicted sequences rather than indisputable facts. It’s bonkers. TA-DA!!! So. Damn. Good.

Oh, and we encounter this film in a burgundy red room set with fantastical objects – geodesic cabinets of curiosity and an immense stone crab – Drama 1882 takes the year 1882 and Egypt’s seminal Urabi revolution (1879–1882) against the imperial rule as starting point. His musical staging – which is at once hilarious and irreverent – recasts the narrative lens on a sequence of events that began with a café fight, erupted into riots, and ended in a full-scale bombardment of Alexandria by British forces and the historic Battle of Tel El Kebir.

As the narrative arc is complete, we are jollied along with foot-tapping beats. We can always see it. Shawky loves a historical rendition; in El Araba El Madfuna (2012), children come to pay homage to an ancient archaeological city and its surrounding mythologies, while in Cabaret Crusades (2013), medieval clashes between Muslims and Christians become a Homeric trilogy retold from an Arab perspective. In his new musical film for the Egyptian Pavilion, something marvellous happens – it’s hilarious, and that will have a more lasting, broader cultural impact. I would love for Shawky to meet Sacha Baron Cohen, AKA Ali G. This was a strong contender for the Golden Lion.

‘Listening All Night To The Rain’ by John Akomfrah, representing Great Britain, is an epic, all-consuming, heart-wrenching body of work in VIII Cantos – and it needs a feature film length of time to absorb (which hopefully means this show will travel). Taking its title from Su Dongpo’s poetry (1037 – 1101), which meditates upon the transitory nature of life during a political exile, Akomfrah’s exhibition is also a manifesto, inviting us to listen as a form of activism. Poetry runs through everything – like water – and carried along by the crowds – petals on a wet black bough – we grasp at meanings formed between the seeing and heard. And because it is gentle and brutal, our mind is tumbled smooth like pebbles in a river bed, ready for the taking.

We enter the Pavilion from the basement (a simple reminder of how many of us access places we are not welcome). We encounter sets of bifocal screens, with moving images split on a horizon like a seascape – as if seeing the world in every direction from a little boat, lost at sea. These time-looped vignettes are set into sculptural installations, painted in darkening hues that reference the colour fields of Mark Rothko, occasionally inscribed with quotes. Such as this:

“Even in the vast and mysterious reaches of the sea, we are brought back to the fundamental truth that nothing lives to itself.” Silent Spring (1962) Rachel Carson

And here we are, the sea rising all around us, ready to wash all this beauty away into the significant current – and we know deep down what the answer is: we need to listen to the world and respond by making things beautiful – so that we can wake up to the birdsong. Again. I am grateful for the chance @tarinimalikwas given to curate this with @shaneakeroyd – It’s just totally, utterly brilliant – I want to see it again.

Nigeria Imaginary, commissioned by Godwin Obaseki, Governor of Edo State, and curated by Aindrea Emelife, was a sensation – amplified by soundscapes created in collaboration with Nigerian artists and musicians – so everyone could tune in. Only the second time Nigeria has had the opportunity for a national pavilion – its transformation of the 16th-century Canal Palace and subsequent off-site gatherings rightly secured its place at the heart of international contemporary. Nigeria Imaginary showcases the work of eight leading lights: Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Ndidi Dike, Onyeka Igwe, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Abraham Oghobase, Precious Okoyomon, Yinka Shonibare, and Fatimah Tuggar, each responding to the theme ‘Foreigners Everywhere’.

Ambitious, photogenic and wildly original, this exhibition has roots in the Mbari Club, a cultural hub founded in Ibadan in 1961 by Ulli Beier, by a group of young writers, including Wole Soyinka and Chinua Achebe, who believed making art was a duty to the nation. The art community, often called The Art Society, declared itself a “laboratory for ideas” during the early years of independence. Encouraged to explore the paradoxes of myths, limitations of stereotypes and experiences of colonial modernity, artists also gave free rein to their utopian imagination.

Celebrating the tradition of Venetian frescoes, Tunji Adeniyi-Jones emblazons the ceiling with a monumental painting – like an African sun, and Yinka Shonibare builds a clay pyramid out of looted historical artworks from the Kingdom of Benin, reimagined. Precious Okoyomon’s radio tower, which records changes in the atmosphere and transforms them into the sounds of bells and electronic synthesisers, also broadcasts the words of selected Nigerian poets, artists and writers. Meanwhile, the unforgettable new music commissioned and shared was also a reminder that we often hear it before we see it – the spirit of Fela Kuti is still all around.

This exhibition, to the left of the Accademia Bridge at the Palazzo Contarini Polignac until August the 1st, will break your heart into pieces and then fill your soul with a bouquet of spring flowers. Featuring 22 artists presented by the Victor Pinchuk Foundation and the Pinchuk Art Centre, it asks the simple but pressing question: can we imagine tomorrow? Do we have the courage to dream? As a counterpoint to Russia’s war in Ukraine, an ongoing global power struggle that has brought war back to Europe, this exhibition weaves a tapestry of stories and dreams by Kateryna Aliinyk, Allora & Calzadilla, Alex Baczyński-Jenkins, Fatma Bucak, David Claerbout, Shilpa Gupta, Oleg Holosiy, Nikita Kadan, Zhanna Kadyrova, Dana Kavelina, Nikolay Karabinovych, Lesia Khomenko, Yana Kononova, Kateryna Lysovenko, Otobong Nkanga, Wilfredo Prieto, Oleksiy Sai, Anton Saenko, Fedir Tetianych, Anna Zvyagintseva, Roman Khimei and Yarema Malashchuk, Daniil Revkovskiy and Andriy Rachinskiy.

Amidst these overwhelming circumstances, individual creativity will blossom, but it is always at risk. Walking through a room strewn with flowers and up to the first floor, we find a room with five screens resting on the floor, each depicting a different child. We learn that these videos of sleeping children relate to the scandal of the abduction of Ukrainian children by Russians. A little girl looks hauntingly like one of the children I have living with me under the Homes for the Ukraine scheme – orphans who came here with their aunt as refugees. I crumble. This war has so many consequences for all of us, and I have so many questions. Fortunately, I met the artist Dana Kavelina and interviewed her next to her work: ‘It can’t be that there’s nothing that can’t be returned’ (2022). Can our collective struggles jointly create a better future? If so, what does this look like? Next door, a pink rose grows on a giant mound of shit, and for the second time that morning, I weep. This is the heart-breaking vision of resilience. Bravo to the curators: Bjorn Geldhof, Ksenia Malykh, Oleksandra Pogrebnyak, and Oksana Chornobrova.

Devising a structure of exchange between her extended group of artist friends, Horvat invited each to contribute a small-scale work that reflects the idea of “foreigners everywhere” and relies on their network of friends to deliver it. Look closely, and you’ll find the catalogue to our times—show in complimemt to Horvat’s own poetic collages, made from observations during her time in Venice.

So often, we ignore the horrendous collateral shipping and waste costs of international shows (especially short-term octopus art fairs). However, this simple concept, replete with an elegant, modular archival system, creates the opportunity for a hand-held network of trust and engagement—like our journey there on arrival with @kristinhjellegjerde to deliver a new work by @sintatantra for the show.

In this appropriately titled show – Welcome! A Palazzo for Immigrants – Omar Yousefzada investigates hard-core, urgent themes (displacement, migration, class and climate change) through the soft but durable textile and the complex but fragile glass medium. Interweaving these themes with new techniques – he provides us with a fresh perspective on his practice in the context of this miracle of a floating city, thus highlighting a mutual precarity. Notably, a series of hand-blown Murano glass sculptures were made in collaboration with the glass masters of Berengo Studio.

Co-curator Nadja Romain says, “The exhibition pays tribute to both Venetian glass and textiles in a dialogue with Osman’s Pakistani heritage. Osman’s interest in the history of glass—which started in the Middle East—and the history of Venice in general nourish his reflections about the migration of cultures, commercial power, and trade.”

“Yousefzada’s practice casts light on displacement and dispossession, fundamental aspects of the immigrant experience,” notes the Co-Curator “In Venice, a place renowned for its production of glass and textiles, his works take on a different dimension given the city’s traditional role as a gateway to the East and an entrepôt of exotic goods and people. The ongoing immigrant crisis in Europe today underlines the exhibition’s significance.”

To coincide with the 60th International Venice Biennale, the Gallerie dell’Accademia is staging the largest exhibition of Willem de Kooning’s work ever presented in Italy. The first exhibition to explore how time spent in Venice and Rome, in 1959 and 1969, shaped his practice brings together 75 paintings, drawings and sculptures. The “Black and White Rome” drawings are shown with iconic works from the late 1950s, and three of his best-loved pastoral landscapes ‘Door to the River’, ‘A Tree in Napes, and ‘Villa Borghese’ are exhibited together. In these, the lingering memory of his trip to Italy manifests in gesture and tone – and we can relate to their thrilling exaltation…

“Willem de Kooning collected from the cacophony of visual excitement, light and movement in daily life to create his lexicon. The impact of any visual encounter could render or generate an idea for moving into a new drawing or painting,” said Gary Garrels and Mario Codognato, co-curators of the show. They call this “a gestalt of glimpses”, which, in our experience of the show, translates into the perception of glimmers. We are mesmerised, and the layout of these masterworks is so elegant. They are variously paired and counterbalanced by his sculptures, and the mind tips into poetry. These unctuous bronzes, richly toned in the darkest of patinas, had morphed out of the building’s polished ebony floor – in ecstatic response to this chorus of works. Little wonder, I saw a gallerist and curator cry.

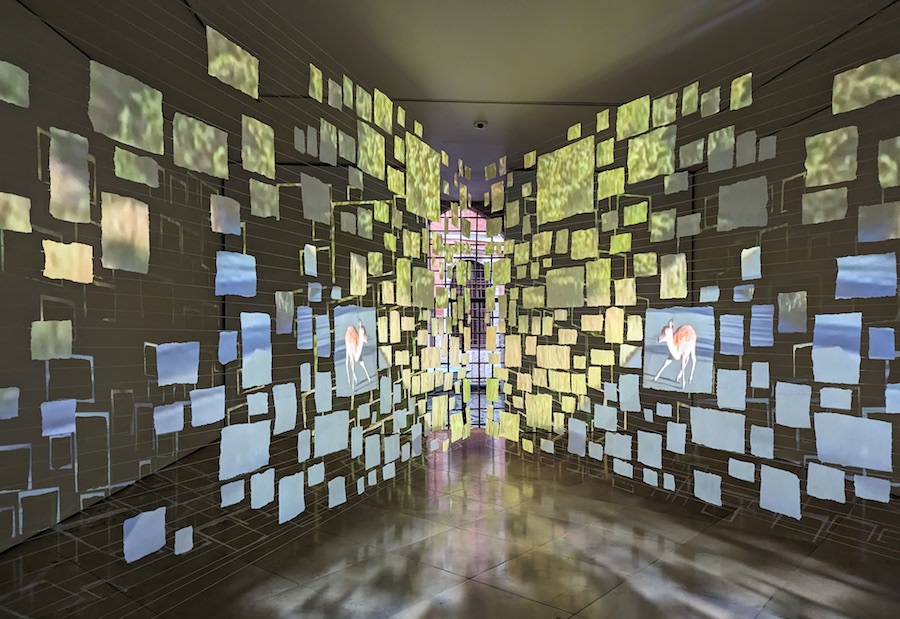

Sarah Sze’s first exhibition at Victoria Miro Venice, the artist’s sixth with Victoria Miro, marks a return to Venice for Sze, who featured in the 1999 and 2015 Biennales and represented the United States with her exhibition Triple Point in the 2013 Biennale.

After a residency there, she created two distinctly immersive environments – one that feels like walking into a sketchbook and the other a mesmeric, museum-grade installation, one of the best things I have ever seen in Miro’s bijou Venice space. A giant web of fine string is drawn into a central point at the back of the room, where a widow frames the shimmering Venetian canal. Onto this, various differently sized pieces of paper with rough edges are suspended in her signature dynamic, floating style. Like a dream catcher, these little pixels of paper catch images projected in their entirety onto the work, then magically reconfigure as individual images in a dance of colour and light that shows the artist’s total mastery of her craft.

Exploring how images and memories are constructed, Sze enchants the viewer with an alternative web. Her moving-image installation, entitled Sleepers, 2024, Sze transforms the gallery with an array of ever-changing projections suspended throughout the space that merge as both memento mori and memento vivere – a reminder that life is transient and also that life must be lived. Just wondrous, strange, and unforgettable.

Top Photo: 60 Venice Biennale Photo P C Robinson © Artlyst