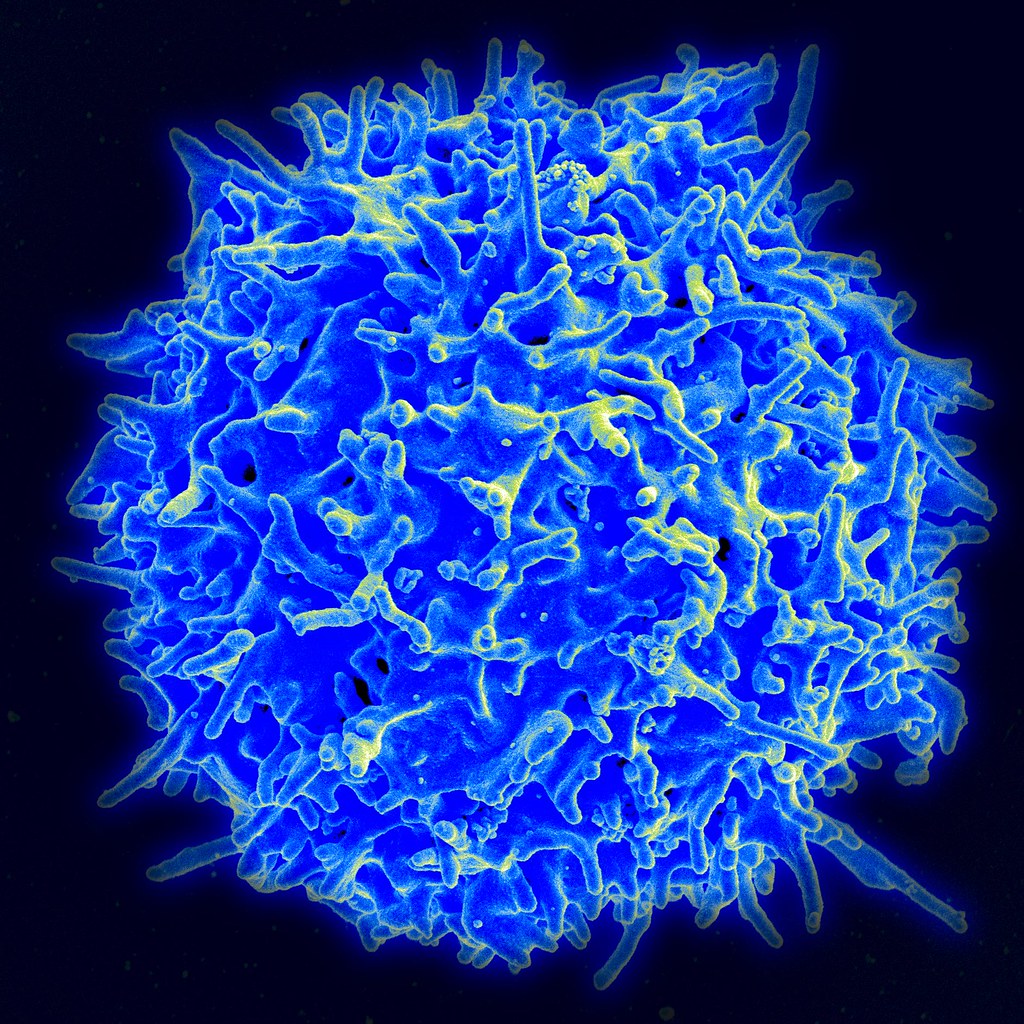

The Short Answer: The Sun’s corona is the outermost part of the Sun’s atmosphere. The corona is usually hidden by the bright light of the Sun’s surface. That makes it difficult to see without using special instruments. However, the corona can be viewed during a total solar eclipse.

About the Solar Corona

Our Sun is surrounded by a jacket of gases called an atmosphere. The corona is the outermost part of the Sun’s atmosphere.

The corona is usually hidden by the bright light of the Sun’s surface. That makes it difficult to see without using special instruments. However, the corona can be seen during a total solar eclipse.

During a total solar eclipse, the moon passes between Earth and the Sun. When this happens, the moon blocks out the bright light of the Sun. The glowing white corona can then be seen surrounding the eclipsed Sun.

Caution! Eye Safety During a Total Solar Eclipse Except during the brief total phase of a total solar eclipse, when the Moon completely blocks the Sun’s bright face, it is not safe to look directly at the Sun without specialized eye protection for solar viewing. For safety information, visit the NASA Eclipse Safety Page.

Why is the corona so dim?

The corona reaches extremely high temperatures. However, the corona is very dim. Why? The corona is about 10 million times less dense than the Sun’s surface. This low density makes the corona much less bright than the surface of the Sun.

Why is the corona so hot?

The corona’s high temperatures are a bit of a mystery. Imagine that you’re sitting next to a campfire. It’s nice and warm. But when you walk away from the fire, you feel cooler. This is the opposite of what seems to happen on the Sun.

Astronomers have been trying to solve this mystery for a long time. The corona is in the outer layer of the Sun’s atmosphere—far from its surface. Yet the corona is hundreds of times hotter than the Sun’s surface.

A NASA mission called IRIS may have provided one possible answer. The mission discovered packets of very hot material called “heat bombs” that travel from the Sun into the corona. In the corona, the heat bombs explode and release their energy as heat. But astronomers think that this is only one of many ways in which the corona is heated.

Coronal loops and streamers

The surface of the Sun is covered in magnetic fields. This is the force that makes magnets stick to metal, like the door of your refrigerator.

The Sun’s magnetic fields affect charged particles in the corona to form beautiful features. These include streamers, loops, and plumes. We can view these features in detail with special telescopes.

How does the corona cause solar winds?

The corona extends far out into space. From it comes the solar wind that travels through our solar system. The corona’s temperature causes its particles to move at very high speeds. These speeds are so high that the particles can escape the Sun’s gravity.

Photographing the Corona: The Pursuit of Cosmic Marmels

Embarking on the quest to capture the elusive beauty of the sun’s corona during a total solar eclipse is an adventure that transcends mere photography; it’s a journey into the heart of celestial mechanics and a dance with cosmic timing. The corona, that ethereal outer layer of the sun’s atmosphere, is a sight to behold, but one that requires both preparation and a touch of serendipity to witness.

The tale begins with an innocent query, a friend’s casual mention of the upcoming solar eclipse. At first, the idea of photographing such an event seemed daunting, especially given the specialized equipment often associated with solar photography. The longest lens in my possession was a modest 200mm—hardly the powerhouse one might imagine necessary for capturing the grandeur of the sun’s fiery halo.

Despite the initial reluctance, the seed of curiosity had been planted. Research revealed that the task was not as Herculean as it first appeared. With the acquisition of a simple sheet of solar film, the possibility of photographing the eclipse with my existing gear transformed from a distant dream into an attainable goal.

As the eclipse drew nearer, the logistics of the journey began to take shape. The path of totality—a narrow band where the moon would completely obscure the sun—would pass over the home of family in North Carolina. An email exchange confirmed that, despite a full house, there was room for one more. The decision was made; I was going to witness and capture totality.

The adventure was not without its hiccups. Companions from Ohio, fellow photographers with whom I had planned to carpool, canceled at the last minute. It seemed as though the expedition was destined to end before it had even begun. But fate intervened once more, with a family from New York making a late decision to join the pilgrimage and offering me a ride.

The journey to the path of totality was more than just a physical relocation; it was a transition into a world where the ordinary rules of day and night momentarily paused. As the moon slid across the sun, daylight waned, and the temperature dropped. The world held its breath in anticipation.

Equipped with my camera, now adorned with the solar film, I was ready. The moment of totality was brief but breathtaking. The sun’s corona revealed itself in full glory—a diaphanous wreath of light undetectable under normal circumstances. It was a photographer’s dream, a rare opportunity to capture a phenomenon that speaks to the very workings of our solar system.

The process of photographing the eclipse was a delicate balance of timing and exposure. Multiple shots at varying exposures were necessary to do justice to the corona’s dynamic range. In the fleeting moments of totality, I worked with precision, acutely aware that any misstep could mean missing the shot.

Back home, the real work began. A week of meticulous editing followed, during which the multiple exposures were combined into a single image that captured the corona’s intricate detail and the event’s raw power. The result was more than just a photograph; it was a testament to the wonder of the cosmos and the human spirit’s tenacity.

The aftermath of the eclipse brought a flurry of activity. People across the country sought to repurpose their solar eclipse glasses, donating them to organizations like Astronomers Without Borders, which would redistribute them to others around the world for future eclipses. The collective experience of the eclipse had fostered a sense of community and shared wonder.

In Montreal, the eclipse was celebrated with music and gatherings, as tens of thousands converged in parks to witness the spectacle. The Orchestre Métropolitain provided a live soundtrack to the celestial event, adding a layer of cultural richness to the astronomical phenomenon.

The eclipse also brought with it a wave of concern over potential eye damage. Despite the warnings and the availability of protective eyewear, many feared they had inadvertently harmed their eyes. Fortunately, such cases were rare, and the human eye’s natural aversion to staring directly at the sun served as an effective safeguard for most.

As the eclipse passed and normalcy returned, the myths and superstitions that had bubbled up around the event were dispelled. No, the eclipse did not emit harmful radiation, nor did it affect pregnant women or spoil food. These were but echoes of ancient beliefs, reminders of the awe and fear that celestial events have inspired throughout human history.

The experience of capturing the sun’s corona was more than a photographic achievement; it was a reminder of our place in the universe—a fleeting moment when the alignment of celestial bodies brought into focus the grandeur and mystery of the sun. It was a reminder that sometimes, the most extraordinary sights require us to look beyond the surface, to seek out the hidden beauty that lies just beyond the reach of our everyday gaze.

The image of the sun’s corona, a product of a thousand-mile journey and a week of editing, stands as a personal milestone and a shared treasure. It is a snapshot of an ephemeral instant when the universe aligns, a dance of shadows and light that captivates and humbles, reminding us of the enduring allure of the cosmos.

Related posts:

Solar eclipse 2024: Follow the path of totality

How to Shoot Solar-Eclipse Images & Videos

Simple tips to safely photograph the eclipse with your cellphone