When they entered a Manhattan recording studio on a spring day in 1986 to record the mash-up that would change the world, Run-DMC and Aerosmith were on very different career trajectories.

Run-DMC were rising stars in the then-novel field of hip-hop. Aerosmith were arena-rock dinosaurs — in their mid-30s, but they seemed older — on a downward slope.

The session, assembled by then-fledgling producer Rick Rubin, came at the end of the recording of Run-DMC's third album, Raising Hell. Hip-hop still existed mostly within an underground niche. Rubin thought a joint cover of Aerosmith's 1975 hit "Walk This Way," with its instantly iconic, globally familiar opening riff, might help the rappers appeal to white kids in the suburbs.

He coaxed the reluctant members of Run-DMC into the studio and paid Aerosmith's singer Steven Tyler and guitarist Joe Perry $8,000 to show up. It's an indicator of the former rock gods' prospects at the time that this seemed like a lot of money.

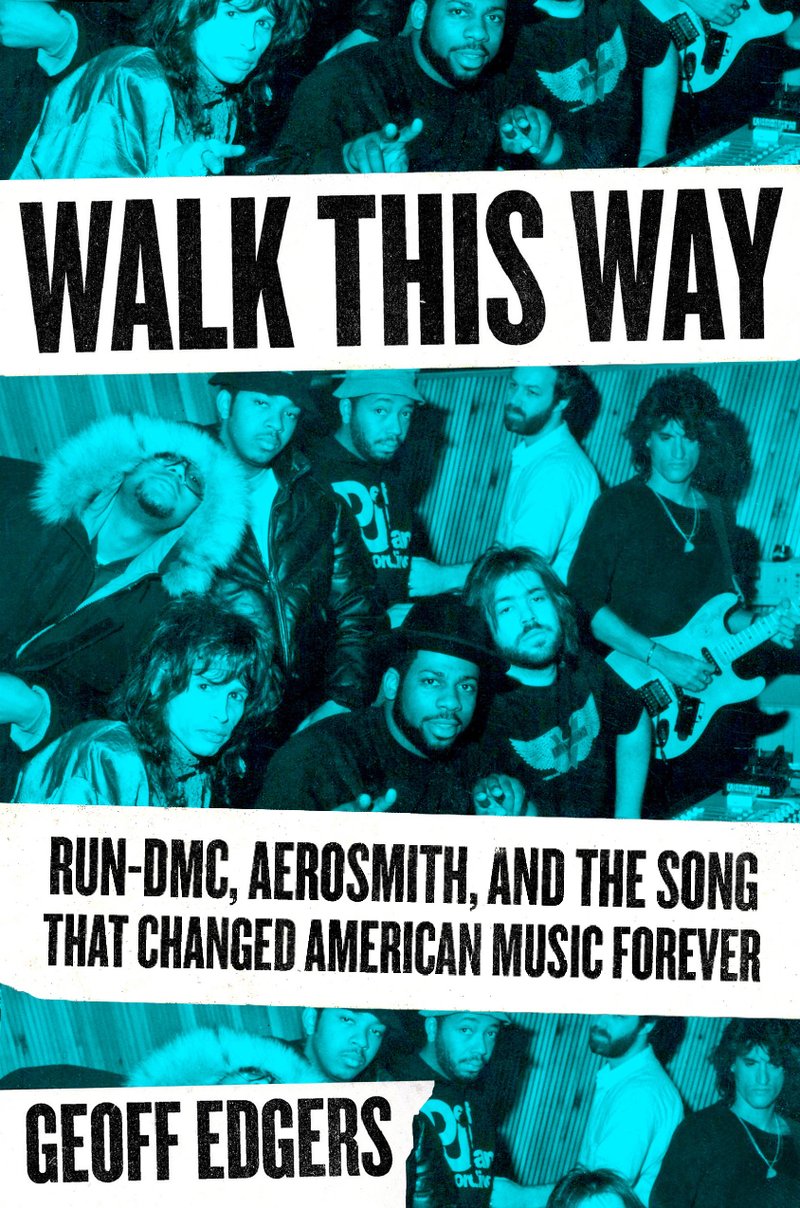

In Walk This Way: Run-DMC, Aerosmith, and the Song That Changed American Music Forever (Blue Rider Press, $27), Washington Post staff writer Geoff Edgers makes a convincing case for the track as a line of pop cultural demarcation: Before Run-DMC and Aerosmith joined forces, rock radio and MTV, the twin engines that powered any hit song, were off-limits to rap artists. After the song became a genre-busting smash, Edgers says, Run-DMC became the first rap group to ascend to pop stardom, the first to ever breach the barricades of rock radio. "By tapping into the classic rock canon and surrendering the chorus to Steven Tyler's distinctive howl, the song basically served as hip-hop's Trojan horse, the music camouflaged enough to give timid programmers permission to play," Edgers writes.

After "Walk This Way" came the deluge: Yo! MTV Raps. Arsenio. Rage Against the Machine. President Obama. That Puff Daddy/Jimmy Page collaboration (not all change is positive).

Edgers' book, birthed from an oral history of the collaboration published in The Post in 2016, shows "Walk This Way" as a blunt instrument of change, the thing that, he writes, "made it safe to be black and mainstream." It's an exhaustively sourced, briskly entertaining read: a ground-level recounting of that 1986 recording session, and a just-enough-information primer on the histories of Run-DMC and Aerosmith, and the early days of rap and MTV.

In their earliest days, Run-DMC, like a lot of hip-hop artists, would rap over the meaty opening riff of Aerosmith's original "Walk This Way." They didn't know its name or who performed it, were only familiar with its beat, the only part they needed. If the song played long enough for Tyler's voice to come in, the DJ was doing it wrong. "That record was done for hip-hop after about 45 seconds," rapper Chuck D tells Edgers.

Years later, Rubin walked in on Run-DMC in the studio, "Walk This Way" on the turntable. Rubin explained the existence of Aerosmith (he was a longtime fan), and told the group to go home and learn the lyrics, because they were going to cover the song. To Rubin, Tyler's lyrics were a kind of scattershot poetry, a rap song in waiting. To the alarmed members of Run-DMC, Edgers writes, it was "some spazzy white dude double-talking through verses that might as well have been the Norwegian national anthem."

Once in the recording studio, the groups eyed one another warily. Perry and Tyler, whose heroic consumption of drugs helped earn them the nickname the "Toxic Twins," spent extended periods in the bathroom. "They were sniffing a lot of coke," Russell Simmons tells Edgers. Run-DMC didn't take the session seriously — they were really worried about a rental car that had disappeared — and had to come back to redo their parts.

The video shoot didn't go much better. The rival camps were uneasy with one another. Aerosmith hadn't been to rehab yet. Stand-ins were hired to represent the rest of their band, whom no one seems to have thought to invite. Tyler and Perry were worried about looking ridiculous, Edgers says, and the rappers viewed the rockers as addled has-beens who should have been thankful for the exposure. "Somebody's riding somebody's coattails," an observer tells Edgers, "and each of them think it's the other."

Both groups would go on to greater stardom after their collaboration, though Aerosmith likely had the better end of the deal. They became multiplatinum MTV darlings, more famous after "Walk This Way" than during their '70s glory days.

After selling 3 million copies of Raising Hell, Run-DMC made an unfortunate feature film, Tougher Than Leather (directed by Rubin, indifferently), battled their record label, opened arenas for Aerosmith and lost their DJ, Jam Master Jay, in a still unsolved 2002 murder.

They would also struggle with the feeling that their breakout hit wasn't merely inauthentic to them, but an unnecessary sellout. If the collaboration had never happened, if Rubin had not chosen Tyler and Perry as his unlikely Ambassadors to White People, it is suggested to Edgers, rap would have soon found its way into the American mainstream anyway.

Lyor Cohen, a fabled industry executive who was in the studio that day, felt the song's easy packaging, its sonic obviousness, forced rap from the underground before its time. The song's success "was jumping to the third act and skipping the second act," he tells Edgers. "Unfortunately, after the third act, the curtain falls."

Style on 02/17/2019