Tomohiro Nishikado’s video game Space Invaders remains the first and last concept for all other “shoot ’em up” video games; the core concept being a single person fighting off a multitude of artificially intelligent enemies. Created in no less than a year, its exquisite attention to imagery and sound, as well as easily understood game play, has offered timeless appeal. What was an amusement of lazy pleasure has since been deemed a work of art, joining the permanent collections of both MoMA and The Smithsonian.

As it celebrates its 40th anniversary, Jon Tannahill of Brisbane – born 17 years after the game was released – holds the Space Invaders world record.

The former world record of 184,870 points was set by Richie Knucklez of New Jersey, USA, who held the position from 2009 to 2018. Tannahill didn’t pip Knucklez at the post – he beat him by a length with a score of 218,870 points. The third highest score on record is only 55,160 points and is held by one of the greatest arcade gamers of all time, Donald Hayes. Most competitive gamers are happy to achieve 5,000 points. It’s a difficult game. Even its creator, Nishikado, has apologised for its difficulty.

With so few people reaching a score of 10,000 points, Tannahill and Knucklez have found themselves in a league of their own, quite literally. They are the only two known players competing for the top score, and in Brisbane on 12 November, they go head to head.

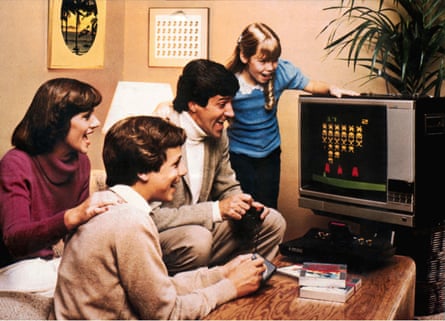

Tannahill didn’t play a game of Space Invaders until 2006. He and his dad were waiting for an order of fish and chips at a local cafe. To bide the time, his dad challenged his son to a game (his dad won).

In 2017, Netherworld – a combined pub and games arcade – opened its doors, inviting local and international gamers to compete on their many pinballs and classic arcade video games from the late 70s to the mid-80s, including Space Invaders, for world record attempts. Tannahill began to frequent Netherworld, meeting other high scorers and world record holders, and set himself a goal: 10,000 points on Space Invaders. If achieved, his score would be in the top ten in the world. Within two months he scored 10,000 points. Within a year he has surpassed every known score performed over the past four decades. His ability to succeed so quickly suggests that everyone else who played Space Invaders for the past half-century is devoid of some quality that Tannahill clearly has.

Now 23, Tannahill admits he wasn’t good at sports and as a kid he didn’t much like running because, as he says, “I was fat”. But, like the majority of Australians, he liked the water. When he enrolled at Brisbane Grammar he chose rowing, thinking it was a paddle on the river. He figured there’d be no cross training. He was wrong. On the first day of rowing he didn’t see water. He ran laps around the oval for an hour and a half, running well behind everyone else. On his second day of rowing, he figured he didn’t have to be the fastest; he just had to beat one person. So he did. Third day of rowing – laps around the oval – he decided he needed to beat at least two other boys. And so on. Eventually, Tannahill lost a lot of weight and earned his way onto the Brisbane Grammar First VIII – an eight-seater rowing boat; and with it, a strict training session.

From age 13 to 18, for four days a week, all year round, Tannahill woke at 4am, got into a boat at 5am to row up to 20km in 90 minutes, in preparation for a 2km race that will exhaust the fittest athlete in less than seven minutes. But, with no requirement to catch or kick a ball, he felt rowing was much better suited to his disposition.

According to Tannahill, the key skill is to be comfortable with being uncomfortable. The most difficult task is acquiring the mental discipline to want to do it again, and again, in order to reach a desired standard: “It’s a sort of discipline, much of the training is learning how to tolerate pain, and how much you’re willing to hurt yourself. It’s gruelling,” he says.

Of course, there is a difference rowing and playing Space Invaders. The former is generally regarded as a noble pastime, the latter is generally regarded as a waste of time. But Tannahill has transferred the cultivated discipline acquired from rowing to Space Invaders.

To claim the world record, Tannahill estimated he would need to play for approximately four hours. Like the rowing machine, Tannahill would be competing against a machine that never tires. From rowing, he’d already learnt how to maintain a pace in order to sustain a desirable result – a set number – a high score. He’d also learnt what was needed to consistently repeat and perform a tiring task for an extended period of time; and he was confident in his ability (as a rower he had numerous state championship victories). Such skills and focus are suited to Space Invaders, except the gross motor skills for rowing don’t seem to have any obvious connection to moving a joystick and pressing a button.

A Space Invaders player moves a joystick, left or right, to position their “laser cannon” horizontally along the bottom of the screen. Then pressing a single button to launch a slow-moving missile at the evenly stacked moving horde of 55 descending ‘invaders’. If the missile fails to hit, the player is forced to wait until the missile exits the top of the screen. Only then can the player fire again. When the player is successful in a hitting an invader, the horde begins to move quicker; fewer invaders equal faster invaders.

Tannahill utilises a method known as “Death Row” – a strategy which exploits the game’s programming to get the maximum available points. Tannahill permits the invaders to descend – the opposite of what the designers intended – allowing for more time and therefore additional bonus points in the form of the “Mystery Ship” to appear on the screen. The danger of Death Row is the invaders being so close to the bottom of the screen, should Tannahill miss one invader, the game immediately ends. All serious competitors make use of Death Row, it’s just Tannahill is better at it.

Knucklez’s game of 184,870 points lasted five hours. Tannahill’s game of 218,870 points took three hours and 40 minutes; a full hour and 20 minutes quicker than Knucklez. The rate at which points are scored is a direct reflection of how accurate a player is.

Most competitive gamers stay clear of Space Invaders, finding it too gruelling; which is why there are now only two great players of Space Invaders. Something Tannahill is fully aware of.

“While I don’t want someone to beat my score, it’s meaningless if there is no competition. It defeats the purpose of having a world record at all. If [Knucklez] takes it back, it keeps the competition alive, even if it’s only me and him defeating each other.”

Tannahill would like to see other competitors turn their attention to Space Invaders. I know for sure I’d offer no threat to his score, or the many scores ranked beneath. But I was curious; what was his advice if I were to try?

He explained his winning strategy in great detail. It involved keeping count of the first 23 shots fired, and every 15th shot thereafter. He told me it was paramount that I don’t lose count. Telling me you can’t hold a proper conversation with others while you play, and there is literally no pause, or rest, or rest room visit. He then explained the method used to identify which side of the screen bonus point will enter, how to navigate through the early skirmish of the game, how to divide the 55 invaders into two columns for safety, and various other tactics. Rowing started to sound much simpler and more inviting. I asked if he, now being a rowing coach, ever tried to coach others at Space Invaders. He had. He even gave a master class to avid arcade gamers. He said their scores improved quickly but plateaued just as quickly. Despite having taught all the required strategies and tactics, none of his class have been able to reach 10,000 points.

“Why that is, I don’t know. [Space Invaders] doesn’t require the most gifted dexterity, or analytical problem solving, but it does seem to require something else. I’m just not sure what.”

Jon Tannahill will go head-to-head with Richie Knucklez on 12 November, at Netherworld, Brisbane.