Click here to subscribe today or Login.

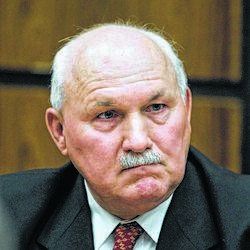

Luzerne County Councilman Stephen A. Urban blasted a new stormwater fee at this week’s council meeting.

“The people are getting nailed left and right in this county over this stormwater fee now, and they’re up in arms. They’re unhappy about it,” Urban said.

The fee stems from a federal Susquehanna River pollution reduction mandate requiring less sediment, nitrogen and phosphorus washed into the Chesapeake Bay over the next five years.

Councilman Harry Haas agreed with Urban, saying solutions to the “incredible federal overreach” should be shouldered by the state and federal governments.

“It’s laundering responsibility and the payment and cost for these things to the local taxpayer. It is inherently unfair,” Haas said.

Council Chairman Tim McGinley stressed county government has no jurisdiction over the fee or mandate. Compliance falls on municipalities, which opted to participate in regional plans, he said.

McGinley said after the meeting that some citizens are mistakenly assuming county council was involved in the fee.

The Wyoming Valley Sanitary Authority (WVSA) is handling the mandate on behalf of 32 municipalities, while three Back Mountain municipalities opted to obtain compliance through the Dallas Area Municipal Authority.

Urban said one of his chief complaints is that he and other Wilkes-Barre residents already pay a $50 city sewer line maintenance fee in addition to WVSA payments for wastewater treatment. He questioned why the city can’t use revenue from the $50 fee to eliminate the stormwater fee for city residents so they are not “hit a second time.”

Wilkes-Barre Operations Manager Butch Frati said revenue from the $50 fee funds maintenance and repairs to city-owned sanitary sewer lines, sewer laterals and stormwater collection systems, which are catch basins and pipes that lead to diversion chambers and eventually the Susquehanna.

The WVSA operates the discharge locations but doesn’t own the web of municipal lines that feed into them, officials have said.

Most of the city lines and systems are antiquated, and the need for capital improvements far exceeds revenue collected by the $50 fee, Frati said.

Some areas of the city still have combined sanitary/storm lines, including the area around Public Square, he said.

Cleaning out catch basins in municipalities is among the work that will be funded by the new stormwater fee, WVSA officials have said.

Frati said city staffers currently handle most of the catch basin cleaning, but any savings yielded by the WVSA assistance would be applied to infrastructure repair and replacement.

“There’s never enough money in that budget line, and repairs are expensive,” Frati said. “We’re just treading water here.”

Mine pollution

Urban also questioned the logic of targeting stormwater when so much pollution from coal mines ends up in the river.

“Stormwater is probably some of the cleanest water there is,” Urban said, referring to runoff from streets and roofs.

As part of the mandate, DEP is requiring municipalities to identify all acid mine drainage in waterways — work that will fall on authorities handling the stormwater programs, officials have said.

However, ending all mine pollution will be a massive and costly undertaking that would require a major government investment, said John Levitsky, a watershed specialist at the Luzerne Conservation District.

Underground mine discharge points were opened up decades ago to stop the polluted water from flooding streets and properties, Levitsky said. He reminds people this will happen again if the points were simply plugged up to stop the pollution — an idea citizens regularly propose to him.

Because these deep mines were long abandoned, there are no entities that can be forced to fix the problem today, he said. The sites were actively mined before passage of the 1977 Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act, which required reclamation.

Because filling in the vast network of underground mines is not feasible and could create a new flooding dynamic for surface water that currently drains into the mines, the only viable option will be treating the polluted water at discharge points, Levitsky said.

The ideal scenario would be finding a private entity interested in capturing the iron oxide for an industrial purpose to help with the expense, he said. Diverting the water into a wetland or detention pond is one method of getting the iron to separate and sink, so it can be removed, officials have said.

The Conservation District focuses on restoring water quality and improving soil but is not getting involved in the pros and cons of the new stormwater fee, he said.

WVSA’s monthly stormwater fees are based on these nonabsorbent impervious areas, or IAs, within each parcel: 100 to 499 square feet, $1; 500 to 6,999 square feet, $4.80; and 7,000 square feet or more, $1.70 for each 1,000 square foot of IA.

DAMA opted for a temporary flat stormwater fee in 2019, with plans to calculate impervious areas in time for the 2020 fee. In 2019, property owners in its participating municipalities will be charged a stormwater fee of $60 a year for each “equivalent dwelling unit,” or EDU. Most residential properties have one EDU, and commercial properties typically have more than one.