Honorary Super Bowl captain Trimaine Davis rewarded SDSU’s faith in him

Orphaned as a child, Davis put his San Diego State degree to work helping students from underserved communities

He didn’t get in.

Trimaine Davis was a 6-foot-7 basketball player from Pittsburg High in a gritty industrial burg on the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. He had been in special education for nine years. He met minimum eligibility standards for an NCAA athlete, but San Diego State’s admissions office reviewed his application, looked at his transcript, shook its head … not college material.

This was late 2000. Steve Fisher had come to SDSU a year earlier to rescue a moribund men’s basketball program that had one winning season in the previous 14. The crazy part was Davis wasn’t a highly rated recruit but a raw athlete who would average 3.3 points, start only 13 of 98 career games and never make a 3-pointer for the Aztecs.

Fisher wanted him anyway, badly.

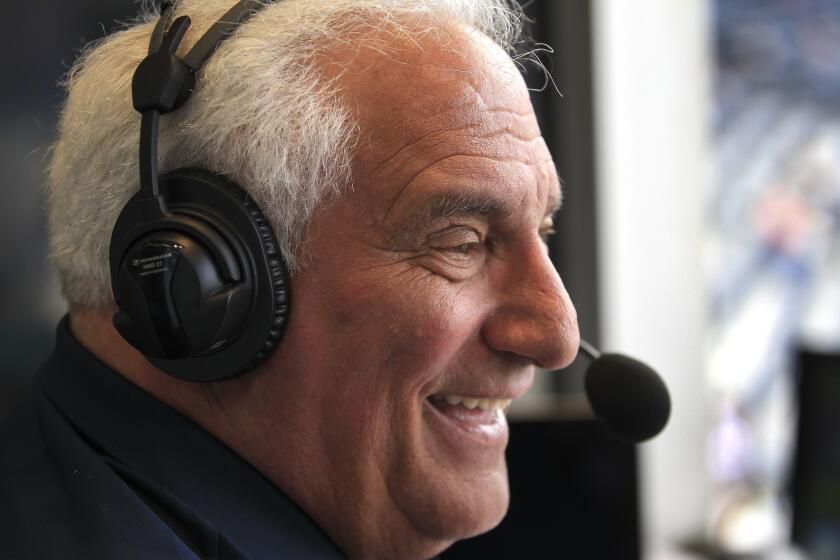

“I was tactful but aggressive enough to say, ‘You don’t know the story, you don’t know the person,’ ” Fisher says now.

He convinced Sandra Cook, the associate vice president for enrollment management, to meet with Davis in person. Davis sat across from Cook, looked her in the eye and told her his story: born addicted to crack cocaine, a ward of the state until his paternal grandmother adopted him at age 3, a mother who died from a brain aneurysm when he was 14, a drug addict father who died from AIDS less than two years later, grandparents who never got past sixth grade in school, parents who never graduated from high school. He just wanted a chance.

“He did what he’s done with everybody,” Fisher says of Davis’ meeting with Cook. “He impressed her enough to the point to where she said, ‘I’m going to do this because my heart tells me this is the right thing to do. But … this better be successful, for everybody’s sake.’ ”

You can watch the coin toss before Super Bowl LV on Sunday afternoon to get the answer.

Davis will be part of the ceremony before the Kansas City Chiefs and Tampa Bay Buccaneers meet at Raymond James Stadium in Tampa, Fla. Not as a player, but one of three “community heroes” selected as honorary captains by the NFL for “their dedication and selfless commitments to helping others.” Amanda Gorman, the 22-year-old poet who gained instant fame at President Biden’s inauguration last month, will read a poem she composed specially about the three.

“There are a lot of things about me on paper that, if you look at it, would say that I’m not supposed to be where I am,” says Davis, 37, who now lives in Los Angeles. “But all those things made me that much more determined to get to where I am.”

Where he is now: an undergraduate degree in African-American/Black Studies from SDSU, a master’s in educational leadership and administration from CSUN, the retention coordinator for the VIP scholars program at UCLA, the founder of the Black Male Initiative at CSUN, similar roles at Long Beach State and Cal State Fullerton, a tireless advocate for historically underserved student populations.

One of his most passionate causes is bridging the digital divide in disadvantaged communities, something he says has existed for years but became particularly acute when education transitioned online during the pandemic. He secured and distributed laptops, tablets and Internet hotspots but then took it a step further, hosting tech workshops to teach people how to properly use them.

“We couldn’t make assumptions that students and families understood how these devices worked,” Davis says.

The connection to the NFL came through Angela LaChica, a San Diego native who founded a sports marketing agency and serves as managing director of the Players Coalition that promotes social justice issues by professional athletes.

How did she know Davis? She was a student manager for Fisher’s early teams at SDSU.

Davis learned of the honor during a routine Zoom call last month about his digital divide work with the NFL. An affable, articulate man of many words suddenly was without them.

“I’ve been thinking about this a lot,” Davis says now that he’s had a chance to process it, “because it is such an incredible honor to be seen on such a mega platform as the Super Bowl. I truly feel unworthy. The thing I think about the most is the folks who have invested time in me. When the news came out, every person that has an impact in my life, particularly when I was a young man and figuring myself out and wanting to go to college, I made sure to personally thank them.

“And one of those people was Coach Fisher.”

Here was their exchange on a virtual news conference earlier this week:

Fisher: “You are the epitome of what it means to give. You are also a young man who has taken advantage of every opportunity that’s been presented to him and run with it. Rather than saying, ‘Look at all these obstacles that are in front of me,’ you have said: ‘I’m going to succeed, I’m going to be successful.’ You always looked forward to the next day.”

Davis: “I have to say, Coach, this is as much your honor as it is mine. Without you, I would not be here. And I will never forget that.”

Marvin Menzies, an assistant coach on Fisher’s staff who handled recruiting, discovered Davis and suggested they pursue him. Fisher flew to the Bay Area and met with Davis and his grandmother.

They talked for three hours. Basketball was rarely mentioned.

“It wasn’t like a typical recruiting visit,” Fisher said. “I felt he had a quality in him, and it’s hard to describe, that would help our program grow as a result of him being in it. I knew he wasn’t going to be our best player. But I knew he could be a very good player and contribute and be part of teams that were successful and did things the right way and treated people the right way and played selflessly.

“He’s always been a giver rather than a taker. I sensed that in him. There was something about him, where if you needed his last nickel he was going to give it to you.”

An improbable bond was forged. The former high school math teacher from Herrin, Ill., with homespun Midwestern aphorisms who uttered “jiminy crickets” when he got mad and warsh your mouth out for a water break. And the teenaged son of drug addicts.

Fisher trusted Davis enough to stake his reputation on him. Davis trusted Fisher to change his life.

“I knew that, and Trimaine knew that,” Fisher said. “I told him, ‘You’re going to set the tone for my credibility for everybody on the academic side of campus. If you fool around and don’t do your job and all of a sudden are academically ineligible, then I’m going to be held responsible. The next time, I’m not going to be able to get a person in. You can set the table for future generations of players. But you have to perform.’

“Trimaine knew that people cared about him, and he wasn’t going to disappoint. He wasn’t going to let them down. But on paper, it didn’t look like maybe he could do it.”

There would be more obstacles. His teammate and best friend from high school drowned a week before graduation (and Davis wore his No. 20 at SDSU to honor him). A knee injury forced him to redshirt in his first year on campus. He averaged 6.8 and 5.1 minutes per game in the next two. He fathered a child back home in Pittsburg. He struggled academically and needed to spend twice as much time in study hall as his teammates.

But he embodied another Fisher truism: Don’t make me coach effort.

Davis emerged as the rare leader who didn’t start or post big statistical numbers. In the locker room after the final game of the 2004-05 season, Fisher named him the only team captain for the following season without hesitation.

“Leadership is a tremendous asset to any program,” says current Aztecs head coach Brian Dutcher, then the lead assistant on Fisher’s staff. “When you can get a leader, especially one that’s not in the starting lineup but provides inspiration to everyone on a daily basis, it makes a difference. I’ve always said there are two types of teams, player driven and coach driven. And player driven are always better.”

In a late January game at Wyoming, the Aztecs were down two points with time running out in overtime when Brandon Health launched an air ball. Davis rebounded it, scored and was fouled with .3 seconds left. As the players waited for the officials to verify he beat the buzzer, Davis, a career 53.4 percent free throw shooter, walked over to Fisher and said: “Coach, don’t worry, I got this one.”

He made it. The Aztecs won, claimed their first Mountain West regular-season title by a single game and ultimately reached the NCAA Tournament.

Davis was asked if he carries any lessons from Fisher into his present life.

“Everything, are you kidding me?” he laughed. “I say a Coach Fish quote every single day, whether it is, ‘It’s always funny when it’s someone else,’ or ‘If something you did yesterday still looks good to you today, you haven’t done anything today,’ or ‘Eyes and ears.’ Coach Fish is in me. His philosophy is the philosophy I use to work and connect with students.

“I don’t think Coach Fish gets enough praise for how incredible of a teacher he is. He is a grand teacher, as far as I’m concerned. I know people talk about John Wooden, and that is deserved. But I would put Coach Fisher right next to John Wooden.”

Fisher invoked the legendary UCLA basketball coach to describe his pride. Someone once asked Wooden what kind of team he had; Wooden replied to get back to him in 20 years and he’d tell him then.

It hasn’t quite been 20 years, but Fisher is pretty sure he has his answer.

One of the three honorary captains Sunday in Tampa is Suzie Dorner, an ICU nurse from Tampa General Hospital who lost two grandparents to COVID-19. Another is James Martin, a Marine Corps veteran from Pittsburgh (Pa.) active in the Wounded Warrior Project.

And one is the 6-7 orphan who wasn’t initially admitted to SDSU.

“I’m going to try my best to embrace the moment as much as possible,” Davis says, “but I also know I also have a responsibility to uphold when I get back and make sure I continue to live up to every, single aspect that has allowed me to get to this point. I don’t want this to be in vain.

“I honestly don’t want this to be about me, you know, because it’s not. I’m the representation of a village of folks who have helped me along the way. But, man, this is incredible. I never would have imagined something like this could ever happen to me.”

Sign up for U-T Sports daily newsletter

The latest Padres, Chargers and Aztecs headlines along with the other top San Diego sports stories every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.