There will never be another Billy Graham, because the world that made him possible is gone

As word of Billy Graham’s death spread on Wednesday morning, commentators observed that since he retired in 2005, no evangelical leader has emerged to occupy his unique place in American society.

But even if there were anyone out there with the same talents that enabled Graham to represent all of evangelicalism, we likely would never know it. The cultural context in which Graham became one of the most important religious figures in American history was radically different than the one that exists today.

“The America that emerged from World War II and the Great Depression was exceptionally unified and cohesive, and possessed of an unusual confidence in large institutions,” Yuval Levin wrote in his 2016 book, “The Fractured Republic.”

“But almost immediately after the war, [America] began a long process of unwinding and fragmenting,” Levin wrote.

And so, the fact that American Christianity hasn’t given rise to a leader like Graham over the last two or three decades isn’t just a result of the fracturing of evangelicalism into different factions — the slick prosperity gospel of Joel Osteen, the strident right-wing triumphalism of Graham’s son Franklin and the theologically precise new Calvinists, to name just a few.

It’s also a story about the fragmentation of American life — arguably a reversion to the norm in American history rather than a departure from it.

The culture of mid-20th-century America was unusually cohesive and uniform. The mindset of most Americans was oriented toward joining groups and being part of something bigger. World War II also produced an increase in religiosity in general among Americans. “There was an upsurge of interest in religion in America at just about every level, from healing-oriented tent revivalists to intellectuals,” historian George Marsden said. “Especially in the late 1940s, even some mainstream thinkers talked about whether some sort of Christian renewal might be necessary if Western Civilization were to recover from its recent debacle.”

But as that cultural consensus gave way to the iconoclastic 1960s and 70s, America became more individualistic, less inclined to trust institutions. The Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, even the shock of the gasoline shortages all played a role.

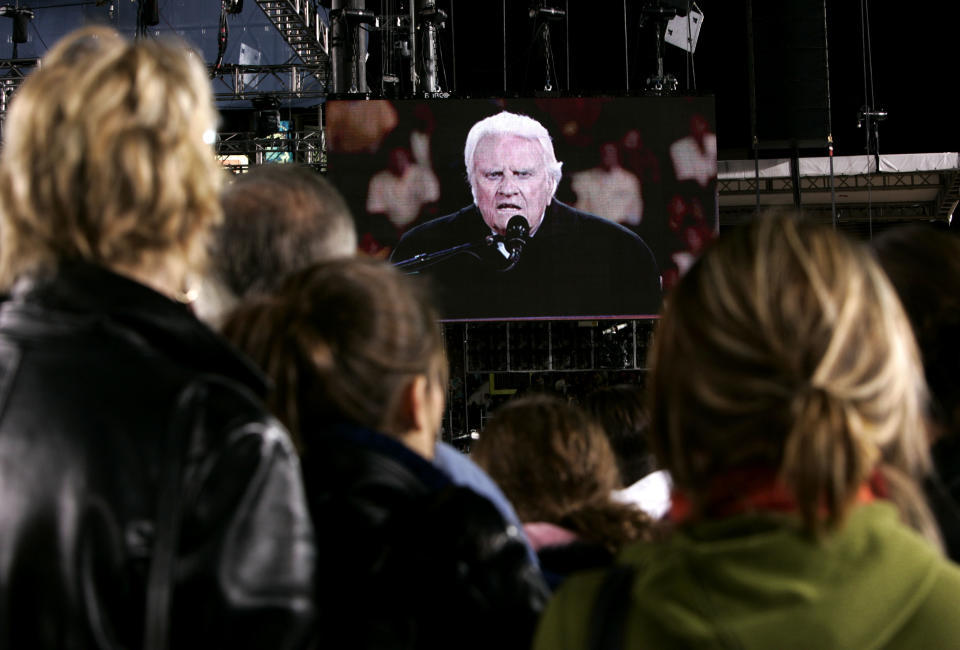

Slideshow: Evangelist Billy Graham is dead at age 99 >>>

The 1980s and ’90s saw an added element of hypermaterialism. And at the start of the 21st century, the centrifugal effect of the internet and the 2008 economic crisis drove the trends toward fragmentation and institutional distrust.

And so the simple answer as to why there are no clearly recognizable evangelical spokespersons representing this huge swath of the country, is that the Christian church in America isn’t immune to the forces shaping the rest of public life.

We saw this dynamic at play as Donald Trump entered the Republican presidential primary, and a common question in political circles was, “Who in the establishment is going to stop him?” The answer, after a moment’s reflection, was “no one. There is no establishment.” American politics has been reformed to the point that the parties are mere shells. Their institutional power is a fraction of what it used to be.

And American evangelicalism has always been deeply populist and anti-institutional. The Great Awakening didn’t happen in established churches so much as it did in open-air camp meetings, where people flocked to hear itinerant preachers like George Whitefield and Charles Finney. Devout adherents were recruited from the lower rungs of society and among those without political power, who formed their own churches, separate from those that served the upper classes.

So Graham came along at a unique moment in American history where a megastar preacher could be the spokesman for the nation’s Christian population.

And even as he reached the heights of his influence and fame in a cohesive and fairly uniform culture, Graham’s evangelism was not establishmentarian. It was populist and non-institutional. He did not usually preach in churches. Rather, his “crusades” were in stadiums and convention centers, much like the accessible camp meetings of the Great Awakening.

Many who converted to Christianity at his events, or reconnected with their faith, began attending a local church after their experience. But despite that, Graham’s “evangelicalism set the accountability structures of churches and denominations aside,” said Jonathan Leeman, editorial director at 9Marks, a support organization for theologically conservative churches.

“Instead, it sought to unite Christians around the gospel and evangelism,” Leeman wrote in an email.

The very term “evangelical” was one that Graham himself popularized. “‘Evangelicals’ in a way was made a category by Billy Graham,” said Frances Fitzgerald, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and author of the 2017 book “The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America.”

He resurrected the term “evangelical” because he was at odds with Christian fundamentalists like Bob Jones who wanted a more distinct separation from non-Christians. He “recreated the term ‘evangelical’ to describe conservative Protestants who were not fundamentalists,” Fitzgerald said.

In fact, Graham was a unifying leader at a time when “American Protestantism was being torn by polarizing forces,” said Skye Jethani, a former executive at Christianity Today magazine, which Graham founded. “Progressives in the mainline denominations advocated for a form of Christianity that accommodated modern ideas. Some went so far as to deny miracles, like the resurrection, that had been foundational to Christian orthodoxy. Many questioned the authenticity and authority of the Bible.”

“On the other side were the fundamentalists holding firmly to the inerrancy of Scripture, but also calling for a separation from society and its perceived profanities. Billy Graham emerged as the flag bearer of a third way that combined a commitment to the authority of the Bible affirmed by the fundamentalists with a positive form of social engagement advocated for by the progressives,” Jethani wrote in a direct message on Twitter.

The rise of television also coincided with Graham’s ascendance, a development that allowed him to reach 200 million people over the course of his career through broadcasts of his events, in addition to the 80 million people to whom he preached in person.

But the divisions among evangelicals are so deep now that many American Christians who in the past would have identified as evangelical are now questioning the usefulness of the term. Many of these people came to this conclusion after watching a majority of evangelicals — as defined by pollsters — vote for Trump. The fact that Graham’s own term – which served its purpose well for decades — is now being abandoned by some is an indication of how far American Christianity has drifted from the relative cohesion of the post-war era.

“There will never be another Billy Graham,” Justin Taylor, an influential evangelical writer who is senior vice president at Crossway Books, a Christian publisher, wrote in an email. “He was a once-in-a-generation (or beyond!) person, with the combination of charisma, good looks, media savvy, and connections, in a world where there were fewer options to choose from.”

America is now the land of endless options. But perhaps the introduction of infinite variety has reduced the possibility for greatness.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Ex-FEC chief lawyer: Trump attorney may have made a ‘colossal screwup’ with Stormy Daniels statement

The deserts of Namibia: Life and photography on nature’s terms

Time is running out for Haitian women and girls in U.S. as refugees

Photos: Gun control rally in Tallahassee; Parkland students meet with lawmakers