North Korean defectors building an army to topple Kim Jong-un

A coalition of North Korean defectors tell Julian Ryall how they are arming and educating their countrymen in preparation for an uprising they hope will end the Kim dynasty

The weapons are being smuggled over the border.

Communication links with the outside world are in place.

Sympathisers, informants and members of the military and regional authorities who have become disillusioned with the North Korean regime know what is coming.

All it will take, insists Choi Min-hyuk, is a spark to ignite an insurrection that he and hundreds of other defectors have been planning for a decade.

And once that flame catches, Choi tells Post Magazine, it will signal the end of a barbaric regime that has caused untold death and despair for the people of North Korea under three generations of the Kim family.

“When I was young, I tried to be loyal to the party and the only ideology we had, juche, which, they tell us, means ‘self-reliance’,” says Choi, who uses a pseudonym to protect himself, his family members in North Korea and his network of revolutionaries.

“I tried to make that my life and, for a while, I was able to do so, but slowly I understood that nothing anyone does in North Korea is of their own free will.”

One tipping point was the five-year imprisonment of his father, for daring to speak about freedom and human rights. Choi’s father had been overheard suggesting that North Korea was a slave state of China, and, previously, of the Soviet Union. Even after he had completed his sentence, the family was discriminated against and isolated.

Further realisation of the reality of the regime came from listening to overseas radio broadcasts, a crime in North Korea that could have cost Choi his life.

“From the moment a North Korean is born, they are taught to be thankful to their leaders and they are taught that they are kind and generous and the best,” he says. “For all North Koreans, [leaders are] our idols. If someone is critical of any of the Kims, they can be killed. The people in the North get no other information and they only hear what the party tells them.

“But I was awakened. I realised it was not true. I was 24 when I realised that it is all a lie. And then my life became even harder. I was thirsty for new things.

“I remember talking with friends and saying it was like we were on an aeroplane that was crashing and that we needed to get out, we needed to escape before it hit the ground.”

After both his parents died in the famine of the mid-1990s, caused by chronic economic mismanagement and the regime’s insistence on provisioning the army first, Choi decided to defect. After three failed escape attempts, in which he was forced to turn back due to heavy security at the Chinese border, he finally succeeded, and arrived in South Korea in February 2008.

Since then, Choi has been instrumental in bringing together like-minded defectors and supporters to build a coalition with one aim: to topple Kim Jong-un, the current dictator of North Korea, and free their compatriots.

And there is an added sense of urgency to their mission.

The United Nations Commission of Inquiry into North Korea’s human rights abuses in February last year reported multiple cases of murder, torture, rape used an instrument of torture, abductions, enslavement and starvation by the regime. This triggered a response from Pyongyang that has horrified activists.

T A coalition of North Korean defectors tell Julian Ryall how they are arming and educating their countrymen in preparation for an uprising they hope will end the Kim dynasty.

“They have offered to open the camps to UN inspectors,” says a campaigner, who is part of Choi’s coalition and will only be identified as Mr Lee. “Which would be a disaster. The regime will have no qualms about killing tens of thousands of inmates just to make it appear that these are not political prison camps. They will turn them into ‘model farms’ or something else harmless.”

In October, South Korean newspaper the Chosun Ilbo reported that 50,000 prisoners held at the Yodok prison camp, which covers nearly 390 sq km and is 115km northeast of Pyongyang, had been moved.

“The regime is transferring the inmates during the night so that their movements cannot be detected by satellites,” the newspaper quoted a source as saying.

“The regime will probably send farmers to the camp to do labour there [when the envoys visit].”

Prisoners sent to the “total control zone” at Yodok, after being convicted of crimes against the regime or denounced as politically unreliable, are never released and, analysts say, it is possible that they are being executed rather than dispersed to other camps.

“Look back at what the Kim regime has done in the past just to survive; this is not conjecture,” Lee says, reinforcing his words by punching a fist into his other hand. “It is a fact that makes us tremble with fear.”

Choi has more reason than many for wanting to provoke a rebellion and liberate the prison network: his surviving relatives are incarcerated in one of the labour camps, with no prospect of ever being released.

“I miss my family,” he says, simply. “When I think about North Korea, I’m too sad. And even though we are here in the South, us defectors are constantly nervous, especially those who speak out against the North Korean regime, because they have agents here and you can become a target.

“And then there is the deep rage we all feel. Fury about the oppression we went through that is still going on just a few kilometres from here. That rage is sometimes almost uncontrollable. I think, for me, that is the worst thing.

“I have nightmares all the time. I can’t eat often.

I’m traumatised …” International sanctions have failed to force Kim to change his ways, say the activists, and his regime is spending more resources on building nuclear and chemical stockpiles, as well as the long-range missiles to deliver them, in order to deter other nations from using force to bring the regime down.

In northeast China, near the North Korean frontier, a defector with the common Korean surname of Kim is overseeing the bribing of border guards and the transfer of small arms to Choi’s network of contacts in the North.

Formerly a senior military official who had been granted the right to live among the elite in Pyongyang, 47-year-old Kim refuses to reveal how he escaped the North, because it could help to identify him and the family he left behind.

Kim uses his knowledge of weapons, military tactics and the North Korean armed forces to plot the downfall of his previous employers.

Given the precariousness of his role in China, Kim is very guarded but will concede that the group’s efforts play to the vices of the North Koreans, as well as attempting to meet the desperate needs of the common people. And, he says, it is quite possible that the Chinese authorities know his name. Another of the group’s 30 leaders, each with different areas of responsibility, admits that one of his team was caught recently and has disappeared.

“For the regime to collapse, there must be a catalyst,” Kim tells Post Magazine. “When that happens, people who know how evil the regime is will want to join the opposition and we have to be ready for that.”

So far, the organisation has procured guns – primarily pistols and submachine guns – as well as hand grenades on the Chinese black market and paid border guards to look the other way as they are sent into North Korea, says Kim.

And while that is a fraction of what the North Korean regime will have to use against the revolutionaries, Kim points to the chaos caused by the numerically inferior French resistance in second world war.

The initial objective will be to seize the armouries that are located in every town and village, where weapons are stored for frequent community military drills, and share those armaments among the local people. Choi sidesteps a question about the number of casualties the defectors are anticipating.

“We have to get the military on our side, along with the police and the internal security agencies,” he says. “We have found our targets in those organisations and we are busy making friends with them.”

Another activist agrees that revealing some of their plans is a risky tactic, but, he believes, the plot already has momentum and widespread support.

“First, it is a warning to the regime and second, it is because we want the international community to be ready for this coming situation,” he says. “Up until now, the international community has listened attentively to reports of the regime’s crimes, but now we really need to eradicate the root of all the evil.

“And that is why we need to take action. Already, we are too late. Countless people have already died and more are dying every day.

“For us, North Koreans are not insignificant ‘other people’; for us, it is a matter of our families being killed or being saved.”

Choi’s priority is spreading anti-regime propaganda within North Korea, at the same time as providing funds.

“A good way of encouraging these people to rise up is by telling them the truth about the regime,” he says.

“Since Kim Jong-un rose to power, there has been no respect for him or his authority. His regime can’t feed the people or even the army any more, so there is a lot of anger and discontentment.

“We are already sending money and, by informing and feeding them, we can win their hearts,” he says, citing the example of the public demonstrations that led to the collapse of the regime of Nicolae Ceausescu in Romania in 1989.

And when that happens in North Korea, every one of the defectors interviewed for this article (Post Magazine spoke to five in total) says they will go “home”, to offer their support and skills to the society that emerges.

Choi says his teams constantly go back and forth to the North – “the border is effectively open to us” – and, along with the armouries, they have identified the initial targets for the revolution.

The plans they outline are intricate and inventive but, they insist, the details are not to be reported. Doing so would give the regime a head start and threaten the safety of their cells in the North, they say. They do agree to reveal, however, that members of their teams are in every significant town in North Korea. They have forged ties with the military – “the army is changing and can be bought now,” he claims – as well as the regional bureaucracies and the secret police.

“The army used to be loyal to the regime because they had to be, but not any more, because they cannot feed them,” says Choi. “So the soldiers and the officers think only about their families. We need to get control of the army. Us defectors all have contacts and friends in the military, and they are thinking the same way as us.

“It’s the same situation in the internal security agencies and the police; they are all angry because the regime does not feed them. And that is what they are telling our contacts inside North Korea. We need to get these people on our side as well, so we are helping them by sending money.”

Other members of the group are agitating workers, many of whose relatives have defected, raising awareness of the vastly better lives they are leading abroad.

Local government officials are assisting in moving the revolutionaries around the country, providing information and even occasionally intervening to protect Choi’s colleagues.

The targets for their initial, coordinated uprisings have been selected and early operations will include the use of drones, large amounts of propaganda and arson attacks.

“The most important thing to create the conditions needed for an uprising is to destroy the regime’s idols,” says Choi. “Every city and town has a research centre dedicated to studying the philosophy of the Kim family.

But really they serve to brainwash the people. Soon, each of these places, along with statues of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il, will be destroyed by people who are enraged at the regime.

“To see these places burning to the ground will make the people understand that Kim is not immortal and the people’s idols will have been smashed.

“The regime terrorises its people; if they are free of that fear, then an uprising will be easy, it will be spontaneous.

“All it needs is that first symbolic spark.”

Where love does not exist

Kwon Hyo-jin is a North Korean defector who was imprisoned for seven years in Chongori prison, or Kyo-hwa-so (Reeducation camp No12). Exclusively for defectors, the labour camp is notorious for being the nation's toughest, where beatings and torture are part of everyday life.

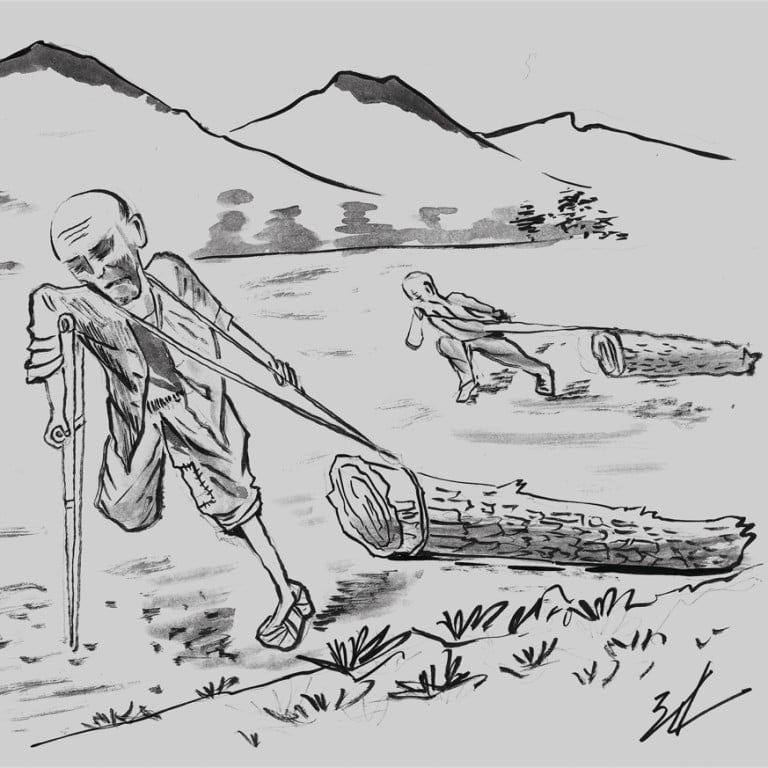

After his release, in 2009, Kwon crossed the Tumen River into China, and travelled to South Korea. Drawing on his experiences, Kwon created illustrations depicting the human rights violations that had occured inside the camp. His work has been displayed in an exhibition called "Where Love Does Not Exist" in Seoul (2011), compiled into a book and presented to a UN Commission of Inquiry on human rights in North Korea. Here are some of his works, with their translated captions.