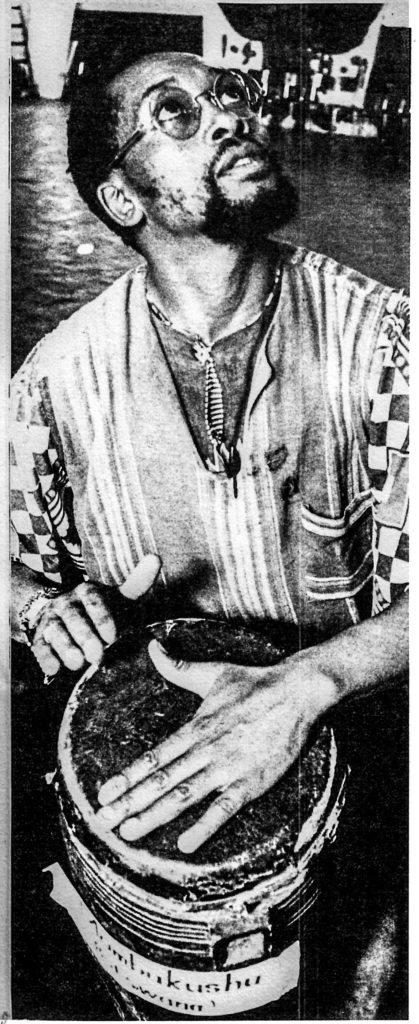

‘Soweto’: Musician and Black Consciousness member Molefe Pheto and other group members were received by Nigerian officials as “heroes from the frontline”. (George Hallet)

From 1966 to 1971 I was a student at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London. Coming out of South Africa, which was not really connected with the rest of Africa, I was hungry to learn what the continent had to offer in the arts and culture. The apartheid regime’s control on cross-continental information was viciously tight.

As an aspiring musician, I made it my duty to visit selected African embassies and high commission offices. My list focused on Nigeria, Ghana, Tanzania and Botswana. I found information about Festac, at the Nigerian High Commission.

On returning home in 1971, I began to travel to Botswana regularly to visit the Nigerian High Commission there. I eventually met the high commissioner, Ms Mohamed, who promised all manner of assistance to me, including the procurement of a visa. I naturally extended the promise of assistance to the Mihloti Black Theatre company, of which I was a founder member. Mihloti had become the vanguard theatre group of an arts movement called Mdali, short for Music, Drama, Arts and Literature Institute. It lasted from late 1971 until 1975.

The group articulated, in its performances and exhibitions, liberatory programmes as an open challenge to apartheid. Mihloti was the most vocal in content. We regularly featured readings by poets such as Don Mattera and Mongane Wally Serote. We also performed the speeches of WEB Du Bois in China; Malcolm X in Harlem; jazzoetry by the Last Poets and Ngugi wa Thiongo’s plays, to mention a few.

The works by Ngugi, Malcolm and The Last Poets were all localised. Return to My Native Land by Aimé Césaire, also localised, was a favourite of our audiences. They, in turn, would begin to search for the banned books and LPs that inspired us.

Mihloti and its mother body, Mdali, were poor organisations. We did not charge entrance fees. What was paramount to us was the message of struggle we spread out.

I was aware of the International University Exchange Fund (IUEF) in Switzerland. We contacted its Southern African representative at the University of Botswana, Professor Phineas Makhurane, who listened to our requests for tickets for nine performers to Festac. Harry Nengwenkulu, a South African exile, had introduced us to Makhurane, his colleague at the university.

The IUEF had agreed to pay for airfares to Lagos. That was how Mihloti made it to Festac, uninvited.

Our members came in as individuals. Some were Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), such as myself. There were members of the Black People’s Convention, student activists of the Students Representative Council in Soweto and so on. During Festac, Fikile and Muntu (actresses in our group) were outed as members of the ANC. They disappeared within four days of our arrival in Nigeria, only emerging again when we boarded the plane back to South Africa. I was told that they had been with Miriam Makeba and her band and had tried to go into exile.

Molefe Pheto (Drum)

Molefe Pheto (Drum)Obviously we had had difficulties receiving South African passports from the apartheid regime. We found someone who bribed the black clerks at the passport offices. The clerks then bribed their white supervisor with a mere bottle of brandy. Even with the bribe, my passport application was initially denied.

We had to travel to Nigeria in batches. The first group was the people from the Soweto Uprisings, including Ben Arnold and Mmakapa. On being asked where they came from by Nigerian immigration officers, they blustered, “Soweto”. I was told that when the officials heard “Soweto”, they responded with, “heroes”. The rest was smooth sailing. The soldiers at the airport even commandeered a car to take the group to the Festac Village.

A few days later, my passport arrived, through a priest in Atteridgeville. At immigration in Nigeria, the first group had asked the officials to be on the lookout for me. And before I could introduce myself, the officials took the document and announced, “Soweto”. I was also received as a “hero from the frontline”. A soldier was seconded to escort me to a waiting room, a driver would take me to the festival village.

We had not anticipated such a welcome. South African passports were not welcome in many African states. We thought, should it be necessary, the first group would request assistance from Makeba. As a last resort, we would summon David Sibeko, the PAC leader, one of the sharpest operators of the liberation movements in exile and under whose command I worked in South Africa.

We didn’t have any rapport with the “official” South African delegations. If anything, they kept us at arm’s length. The PAC’s [delegation] was called The Azanian Dancers and Singers, and the ANC’s was the nucleus of what would become the Amandla Cultural Ensemble.

Quickly, on the fate of these two groups: initially the activities of Amandla, led by Jonas Gwangwa, indicated that they’d learnt some lessons from Festac. But Amandla turned into a vehicle for fund-raising and entertainment and struggle diplomacy. The creativity, commitment to the arts, political direction and history of the black people’s challenges under the oppression of apartheid, were wanting. Comparatively, the theatre and art groups inside South Africa were more confrontational, almost suicidal.

The Azanian Dancers and Singers was, politically, even more in disarray than Amandla. They had been in exile for some time. They had arrived in England and other European capitals through white impresarios, as entertainment and business ventures which had “native” aspects to feed Western palates.

The reason for the icy reception from our fellow South Africans in Lagos was clear: fear. They had been in exile for a long time and were so terrified of apartheid that they thought no one could dare fight it from inside the country. They also feared that we could be spies sent by the security forces. Mostly, they perceived us as competition for attention and support.

Things got really dirty. Soon after I arrived, Nigerian investigators visited our group at the festival village. It was alleged that I had stolen money from a market trader.

It became necessary for me to reveal my PAC connection. The PAC sent Keke Nkula and Ezrom “Eazzy” Mokgakale to the village to intercede regarding our bonafides.

I did not meet Mandla Langa or Keorapetse Kgositsile at Festac, but I was aware of their presence and I was keen to exchange ideas with them despite the fact that I was not ANC. Both would have handled our being in Nigeria intellectually. I met Gwangwa by accident. We’d found him stranded at the National Theatre without transport back to the village and we gave him a lift.

Festac was, in fact, several festivals running simultaneously, and the most important was centred in the artists’ village. There were African-American troupes, musicians and actors, poets and writers from the Caribbean, people from all over the continent. We visited them all informally and at random.

As we’d arrived uninvited, we couldn’t participate in the official programme — it was full to the brim. But there were still colloquium rooms available in the National Theatre. We gave two performances to invited political activists, artists, intellectuals and people we’d met in the village. Both performances were followed by lively discussions.

Even though we were applauded, many feared for our safety, thinking we were foolhardy to be so confrontational. Some even encouraged us to opt for exile, offering to ask their governments to grant us asylum.

Otherwise, individually or as a group, we spent lots of available time exploring Lagos and the festival village. I was keen to reconnect with Mozambican artist Malangatana Ngwenya, whose work we used to exhibit in South Africa during Mdali’s Black Arts Festivals.

One of the things that most stood out for me at Festac was the oneness of Africans. It did not matter language differences. How we talked, walked and the depth of laughter. There were always more similarities than the perceived differences.

After Festac I thought that the Culture and Resistance Conference in Botswana would be open to all artists in exile and inside, irrespective of their specific political orientation. When I realised that it was for ANC members only, or its supporters, I lost interest. The independence of an artist is usually uppermost in my attitude to expressing myself.

PS: When I returned from Festac, I was hauled to John Vorster Square on Commissioner Street, Johannesburg and taken to the same chamber on the 10th floor where I had been interrogated in 1975.

It was clear during the interrogation that the Security Branch were aware of Mihloti’s departure for Nigeria even before we left. They believed Festac was a smokescreen for underground activists like me to meet our handlers abroad for the planning of terrorist activities.

Apartheid spy Craig Williamson had infiltrated bodies such as the IUEF. He would have known of our appeal for funds to go to Festac and facilitated the process to interrogate us on our return. This became clear as I sat in an interrogation room on the 10th floor of John Vorster Square.

This is an edited version of an account first published in the Festac ’77 book. Molefe Pheto wrote And the Night Fell: Memoirs of a Political Prisoner in South Africa. He went into exile in 1977

To purchase a copy of the Festac ’77 book, please visit this website