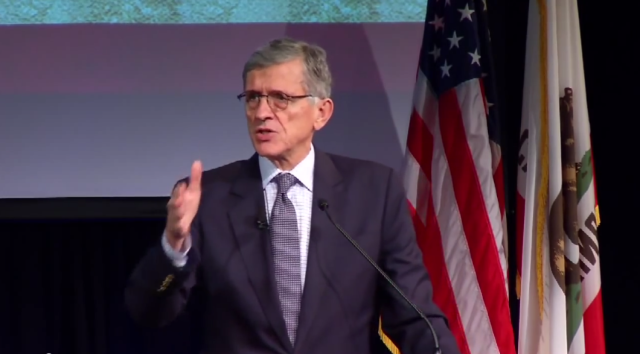

Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler told Republicans in Congress yesterday that their proposals to "improve" the FCC's decision-making process would instead make it nearly impossible to get anything done.

In a hearing titled "FCC Reauthorization: Improving Commission Transparency," the House Commerce Committee's Communications and Technology subcommittee brought in Wheeler to discuss adding new requirements to the commission's rulemaking process. It was the latest in a series of hearings that Republicans have called to chastise Wheeler for decisions opposed by Internet service providers, especially the ruling to reclassify the providers as common carriers and enforce net neutrality rules.

Republicans have proposed wiping out the new net neutrality rules and an FCC decision to boost municipal broadband, but yesterday's hearing focused on changes to prevent future decisions that Republicans don't like.

In 17 pages of prepared testimony, Wheeler explained how the proposed requirements would let opponents of almost any measure prevent it from being enacted. He said the Republicans' proposals would hamstring not just Democratic-majority commissions like the current one but also Republican-led commissions.

The FCC issued a net neutrality Notice of Proposed Rulemaking in May 2014, setting off a months-long discussion period in which the commission received about four million comments from the public. Finally, after taking public comments into consideration, the FCC voted on its rules in February of this year. The final rules were not released until after that vote, as is standard in such proceedings.

Republicans want to change that with a bill put forth by Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) to require the publication of draft rulemakings, orders, and reports when they are circulated to commissioners, which occurs three weeks before a vote. But Wheeler explained that the process—designed by Congress in the first place—is structured as it is for good reason:

Releasing the text of a draft order in advance of a Commission vote effectively re-opens the comment period. That’s because, under judicial precedent, the Commission must "respond in a reasoned manner to those comments that raise significant problems." It won’t take much for a legion of lawyers to pore over the text of an order and file comments arguing that new issues are raised by its paragraphs, sentences, words, perhaps even punctuation. This means the Commission would be faced with litigation risk unless it addressed the comments received on the draft order. This would result in the production of a new draft order, which in turn could lead to another public comment period—and another if a new draft order were released in response to subsequent public comment. The end result: the threat of a never-ending story that prevents the Commission from acting—or forces it to accept undue legal risk of reversal if it ever does. This potential for extreme delay undermines the Commission’s efficiency without enhancing its expertise. And it does so at the cost of the consumers and businesses that rely on Commission decisions.

Republican plan would delay both liberal and conservative proposals

Such a process would have hamstrung the commission during its recent net neutrality proceeding, Wheeler said. But it also would have prevented Republican-led commissions from taking actions in previous years. Wheeler said:

Imagine if the text of the Media Ownership Order or the Declaratory Ruling making DSL services subject to Title I (both adopted by the Commission in 2005) had been released to the public before the Commission had finished deliberating. The public interest groups that appealed the order would have had the opportunity to hold them up for months if not longer. Similarly, companies or trade associations strongly opposed to pro-consumer Commission actions such as the elimination of the sports black-out rule (September 2014) surely would have been seized upon by advocates for the non-prevailing position.

But the problems continue. The draft legislation would apply to every kind of action the Commission might take, including adjudications and enforcement actions. Adjudications are critical to the resolution of specific controversies and enforcement actions, in particular, contain serious allegations against companies. Corporate or individual reputations could be sullied on the basis of claims that have yet to be adopted by the Commission—and may never be.

Republicans claimed that "a number of process failings and procedural irregularities have come to light that not only prevent the public from meaningfully interacting with the Commission, but have prevented the Commissioners themselves from making informed decisions." Michael O'Rielly, one of two Republican members of the FCC, also pushed for changes and said that Wheeler is increasing the use of delegated authority, which lets commission staff make decisions.

"Commissioners are not notified of the vast majority of items that are decided and issued on delegated authority. Like everyone else, we must read the Daily Digest and search the dockets and Federal Register," O'Rielly said.

Wheeler said he objects to a proposal by Rep. Bob Latta (R-Ohio) to "require pre-decisional notification and description of items decided on delegated authority... The reality of delegated authority is that the delegation is the implementation of a decision of the Commission and any decision on delegated authority is always appealable to the Commission. Moreover, the Commission can change a delegation; the Commission’s rules specifically provide that '[t]he Commission, by vote of the majority of the members then holding office, may delegate its functions either by rule or by order, and may at any time amend, modify or rescind any such rule or order.' In sum, Bureaus have delegated authority because a vote of the full Commission gave it to them. It is always reviewable by the full Commission. It is not a bureaucratic frolic and detour."The FCC issued 950,000 delegated items last year, with the vast majority "includ[ing] routine wireless, radio and broadcast licensing and transfers," Wheeler said.

Rep. Renee Ellmers (R-N.C.) proposed requiring the FCC to publish final rules the same day they are adopted. While items are sent to commissioners three weeks before a vote, commissioners sometimes offer comments the night before a meeting, requiring additional work by staff after the vote, Wheeler said. Final orders can be hundreds of pages long and include explanatory text and rationale in addition to rules themselves.

Democratic members of Congress defended Wheeler and the FCC's process.

"When ranking member Anna Eshoo (D-Calif.) got her chance to speak, she said she did not like chairman Wheeler being welcomed to the committee and used as a piñata," Broadcasting & Cable reported yesterday. "She upbraided [Subcommittee Chairman Greg] Walden for using terms like 'charade' and suggested the reform proposals were a way to get back at the FCC for Republican's failure to stop it from approving Title II regulations for ISPs. Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.), ranking member of the full Energy & Commerce Committee, echoed her concerns."

Democrats put forth their own proposals that would require the FCC to make additional information public—but without delaying FCC decisions—and to improve small business participation in FCC proceedings. Democratic legislation would also allow more than two commissioners to meet outside of public meetings, which is prohibited today. Wheeler called this rule a barrier to better collaboration and said that "many former FCC Commissioners from both sides of aisle" support changing it.

reader comments

188