Genetics

What New Our Dog Is Teaching Us About Life

Lesson 2: Don't judge a book by its cover, or a dog by its appearance.

Posted January 29, 2021

You don't need a dog to tell you not to judge a book by its cover. Life teaches us the wisdom of this old cliché easily enough. Take, for example, every time you go into a fast-food restaurant like McDonald's or Burger King. Up there on the wall behind the counter are gorgeous pictures of hamburgers eager to meet your teeth, tongue, and palate. Then you open the wrapping of the actual hamburger handed over to you after payment, and let's face it: What gets revealed once you uncover it ... well, it's usually a far cry from the advertised burger and bun, with or without cheese.

It is conventional wisdom among dog trainers that a canine's understandings of the world are more visual and olfactory than verbal. This is not a startling observation. But I would suggest that however much people like to talk to one another and underplay what their noses can tell them about their surroundings, human beings are basically visual in their dealings with the world — unless, of course, they are blind. If so, then no wonder we can be seduced into buying a burger based on its scrumptious appearance on the flat screens behind the order desk at a burger joint.

But what is the lesson to be drawn from this observation (note the word just used!) about the hundreds of dog breeds now widely recognized by those keeping count of them?

Can you judge a dog by its appearance?

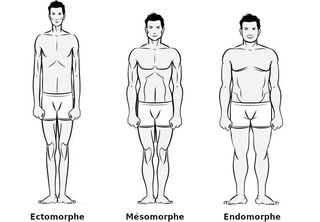

Putting hamburgers aside, it seems a no-brainer to say it is easy for all of us who are human to assume that anything looking as different, say, as a Chihuahua and a Pit Bull or Rottweiler must somehow be different not only in its looks on the "outside," but also on the "inside," too. The kicker here is that if you look inside a dog, what you find there is pretty much the same regardless of the breed.

Therefore, at least nowadays, "on the inside" is commonly taken to mean not in the visual appearance of what is under their skin, but instead "in their genes." Why? Because it is widely accepted that little things called genes inside us somehow not only tell our bodies what they should look like as we grow up, but also how we should use what they are piecing together for us. That is, not only how we look, but also how we behave.

Given this simple logic, it is understandable why it can be so easily assumed that dogs (and people, too) that look different must also behave differently, too.

Is this true?

Charles Le Brun

Back when I was just an undergraduate decades ago, one of my professors, William W. Howells, asked me to cover the private parts in nude photographs of men and women with typist's whiteout so he could use them in a graduate seminar in biological anthropology. These pictures had been taken years before not just as a standardized way of recording how human physiques differ, but also as a formal way to judge whether someone is likely, for instance, to have criminal tendencies, or may be in some other fashion psychologically weak or suspect.

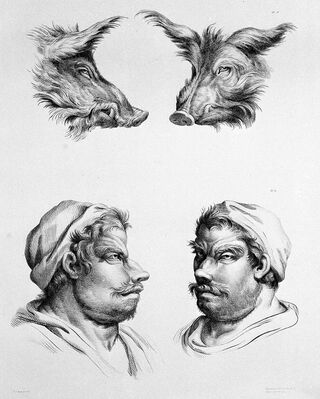

No, I am not making all this up. In fact, the idea that what people look like can be taken as a guide to what they must be like inside psychologically and even morally is an old one running all the way back to Ancient Greece. In the seventeenth century, for example, the French painter Charles Le Brun, the favorite artist of Louis XIV, sketched beautiful comparisons between the anatomical characteristics of animals and humans to discover the "natural inclinations" of the latter — that is, as a graphic way of judging a person's character, say, as “stubborn and timid,” or "obstinate, "wild," and “stupid.”

Again, I not making this up. The very notion that what we look like, physically speaking, somehow determines how we behave ignores how little we are able to do for ourselves at birth, and how much we are dependent on others and what they can teach us if we are to survive on life's journey from the cradle to the grave.

And make no mistake, the same holds true for dogs.

New dog, old tricks

The expression "you can't teach an old dog new tricks" is one of the oldest still popular in the English language. One early version can be found in Anthony Fitzherbert's The Book of Husbandry (1534 edition):

And a shepeherde shoulde not go without his dogge [dog], his shepe-hoke [shepherd's crook], a payre of sheres [pair of shears], and his terre-boxe [tar-box], eyther with hym, or redye at his shepe-folde, and he [the shepherd] muste teche his dogge to barke whan he wolde haue hym, to ronne whan he wold haue hym, and to leue ronning whan he wolde haue hym; or els he is not a cunninge shepeherd. The dogge must lerne it, whan he is a whelpe, or els it wyl not be: for it is harde to make an olde dogge to stoupe.

The consensus opinion today is that old dogs can learn new tricks, but this is not why I have introduced Fitzherbert's quaint words here. I want to underscore instead what he is saying about how young dogs need to be taught old tricks, like herding sheep.

First, note that Fitzherbert tells us a dog is but one of the tools a shepherd must have either with him or ready at hand to do what he needs to do to be a shepherd. Second, his dog — evidently regardless of what it may look like — must learn how to do what he needs a dog to do for him.

Therefore, yes, what a dog does do for a shepherd obviously depends on what it physically can do. But what a dog actually does depends also on whether it has learned how to do what needs to be done.

Here then is the second of the 5 lessons our new dog Emma is teaching us about life:

Don't be fooled by first impressions. Figuring out why a dog does what it does takes time and patience.

Lesson 3 — Anatomy isn't destiny. To find the other lessons Emma has taught us, please go here.

References

Rebecca Rogers Ackermann, Karla J. Larson, Pat Shipman, and Lisa M. Stringer have contributed to this commentary.