Unsafe at Work: A look at harassment, discrimination inside San Diego County’s largest employers

Louise LaFoy, a longtime secretary at the San Diego Sheriff’s Department, was exiting an elevator during a routine trip to the Kearny Mesa headquarters when she crossed paths with Assistant Sheriff Richard Miller.

When she said hello, he put his arms out for a hug. Despite her discomfort, LaFoy felt she couldn’t refuse. The two were alone, and no one saw him slide his hand down onto her buttocks, she said in a lawsuit.

LaFoy was mortified and rushed away. Her mind was racing. Miller was a supervisor. He should know better.

For years after the 2014 incident, LaFoy did what she could to avoid the assistant sheriff. But in 2017, Miller showed up at her office for a meeting. While directing him to a nearby conference room, he again drew LaFoy in for a hug. She said she hoped the presence of a nearby co-worker would protect her. But he groped her again, her lawsuit said.

It took LaFoy months to work up the courage to report being fondled, she said in her suit.

Even though she was a victim, she said the Sheriff’s Department — her department — made her feel like a suspect. At times investigators used intimidating and hostile tactics to get her to discuss the experience, she said.

Then she learned other women also had reported being harassed by Miller. She decided to get her own lawyer.

In early May — after a three-year court battle — Superior Court Judge Katherine Bacal found that Miller had sexually harassed LaFoy, and awarded her $60,000.

The former assistant sheriff, who retired in 2018 and now receives a $181,000 annual pension, denied any wrongdoing.

In closing arguments, defense attorney William Songer, who represented Miller and the county, questioned the idea that the former assistant sheriff would “intentionally take liberties” with someone he was not very familiar with.

In the wake of the verdict, the Sheriff’s Department released a statement that it “does not tolerate sexual harassment of any kind.” Miller did not respond to requests for comment.

LaFoy is one of hundreds of employees who filed claims against their employers in recent years alleging a range of abuses — from sexual harassment to discrimination due to race, age, disabilities, pregnancy or medical conditions, according to documents reviewed by The San Diego Union-Tribune under the California Public Records Act.

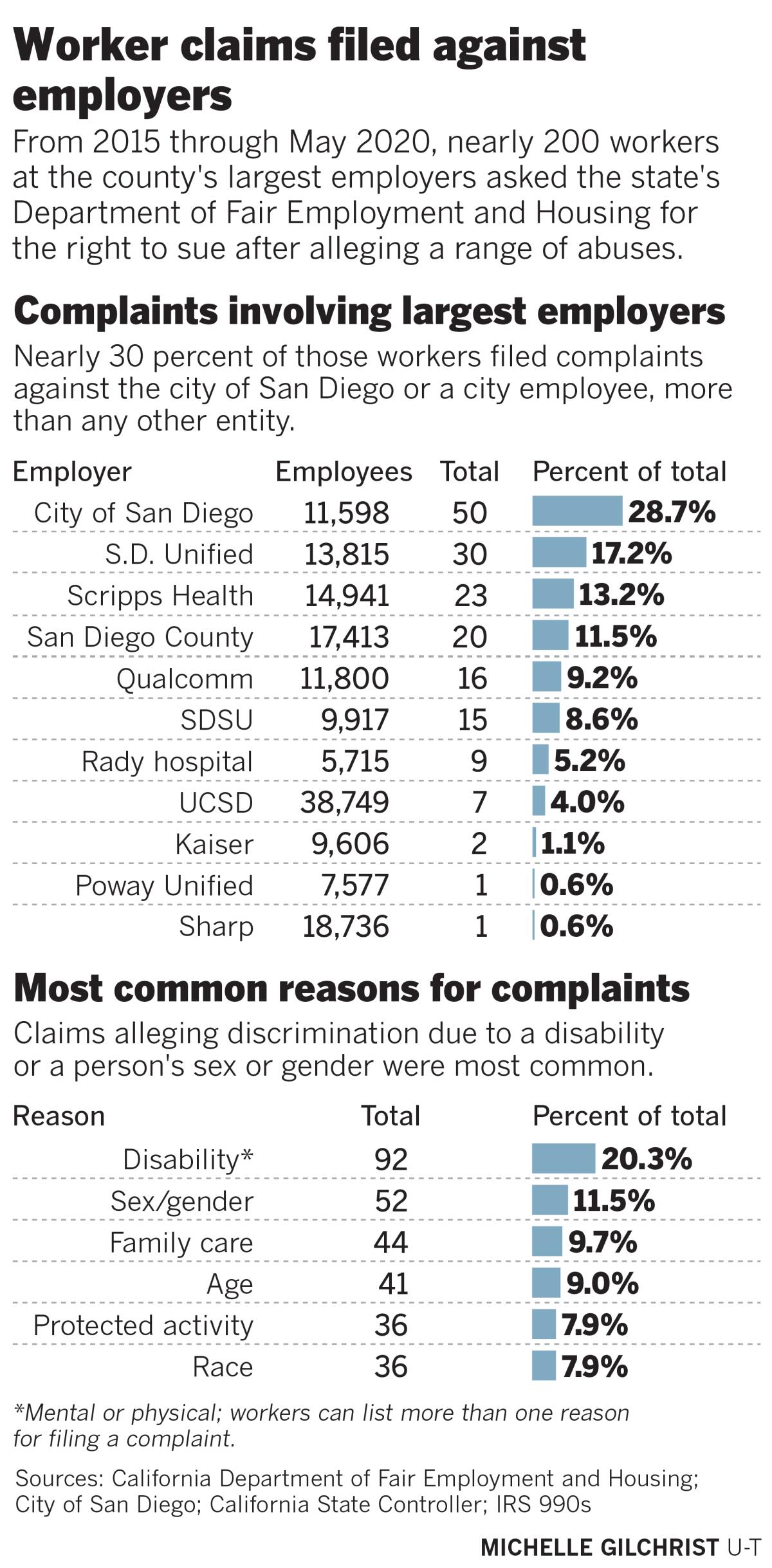

From 2015 through May of 2020, workers from 11 of the largest employers in San Diego County submitted nearly 200 of these sorts of claims to the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing, the regulatory agency plaintiffs must first file with before they can pursue legal action. Data show an average of 29 claims were filed each year. The total peaked at 35 in 2018.

The county’s top employers include the city and county of San Diego, hospitals, educational institutions, information-technology companies and theme parks.

The majority of complaints allege charges of sexual harassment, as well as other forms of discrimination. And although a person’s race or gender was often omitted or redacted from the state documents, lawyers who specialize in employment law say their clients are disproportionately women and people of color.

In one claim filed against the tech giant Qualcomm, for example, a woman said she was repeatedly passed up for promotion, with a supervisor telling her that her “vagina is alienating people.”

At the city of San Diego, an employee said in a claim that they were subjected to repeated unwelcome sexual comments from a co-worker, including one occasion when the man, in the presence of other male employees, described what he believed the victim’s genitalia looked like.

Another San Diego city worker, who had a medical condition that required him to drink a lot of water, said in a claim that he was denied access to bathrooms on the job and ended up urinating in his pants on a regular basis.

Lyndsay Winkley and Lauryn Shroeder on San Diego News Fix:

Attorneys who handle these employee harassment cases say they represent a fraction of the abuses and rights violations that occur at workplaces across San Diego County.

The Department of Fair Employment and Housing, or the DFEH, typically does not receive claims until an employee has already reported the behavior and asserts that not enough has been done to remedy the situation. Even the most legitimate claims do not always end up in court, as employees often are concerned about retaliation or losing their jobs.

“It takes a special type of person to stand up and speak out against something that’s happening at their workplace. It’s your livelihood,” said Aaron Olsen, an employment attorney who practices in San Diego. “A lot of people don’t want to rock that boat, or they’re too scared to.”

Illegal discrimination

The cases that do move forward can be lengthy and emotionally trying battles that often get obscured by secret settlements and non-disclosure agreements. Plaintiff’s lawyers say this clandestine, maze-like legal process regularly hides patterns of abuse against employees.

“Every day I talk to potential clients and I am amazed at what still happens,” said Josh Gruenberg, another San Diego labor attorney. “After all of the news about Harvey Weinstein and the #MeToo movement. You just wouldn’t believe it.”

Employers often say that the safety and well-being of their employees is a top priority.

Many companies require a variety of training, with some being mandated by the state, that teaches managers and workers how to identify, prevent and intervene if misconduct is witnessed. Organizations often craft specific policies that ban sexual harassment and other forms of discrimination.

Lawyers who defend companies against these sorts of claims said many work places, especially large ones, are quite motivated to ensure that discrimination does not occur since resulting lawsuits can be very costly, both in time and money.

California is home to some of the most progressive employment laws in the country. But it’s also an at-will employment state, meaning employers can fire workers at any time for any legal reason. As a result, labor lawyers say, a host of unfortunate behaviors have been found to be legal, including actions that may go against company policy.

“Courts have held that if termination is the ultimate bad thing that can happen to an employee, then everything up to and including termination is also fair game,” Gruenberg said. “That includes treating people differently. That includes nit-picking their work. That includes bullying, embarrassing someone in front of their co-workers, yelling, badgering. All of that stuff that people generally see as harassment, is legal. And that’s always a shock to people.”

But state and federal law dictate that certain forms of harassment and discrimination are illegal. In California, employers may not discriminate against people based on race, ethnicity or color; religion or creed; age; gender; disability; sexual orientation or gender identity, medical conditions, and several other protected characteristics.

When those rights are violated, an employee can file a claim with the Department of Fair Employment and Housing seeking permission to sue.

Although the DFEH does not review all employment-related lawsuits, the claims filed with the agency illustrate the kinds of abuses workers across San Diego County say they suffer at the hands of their employers or colleagues.

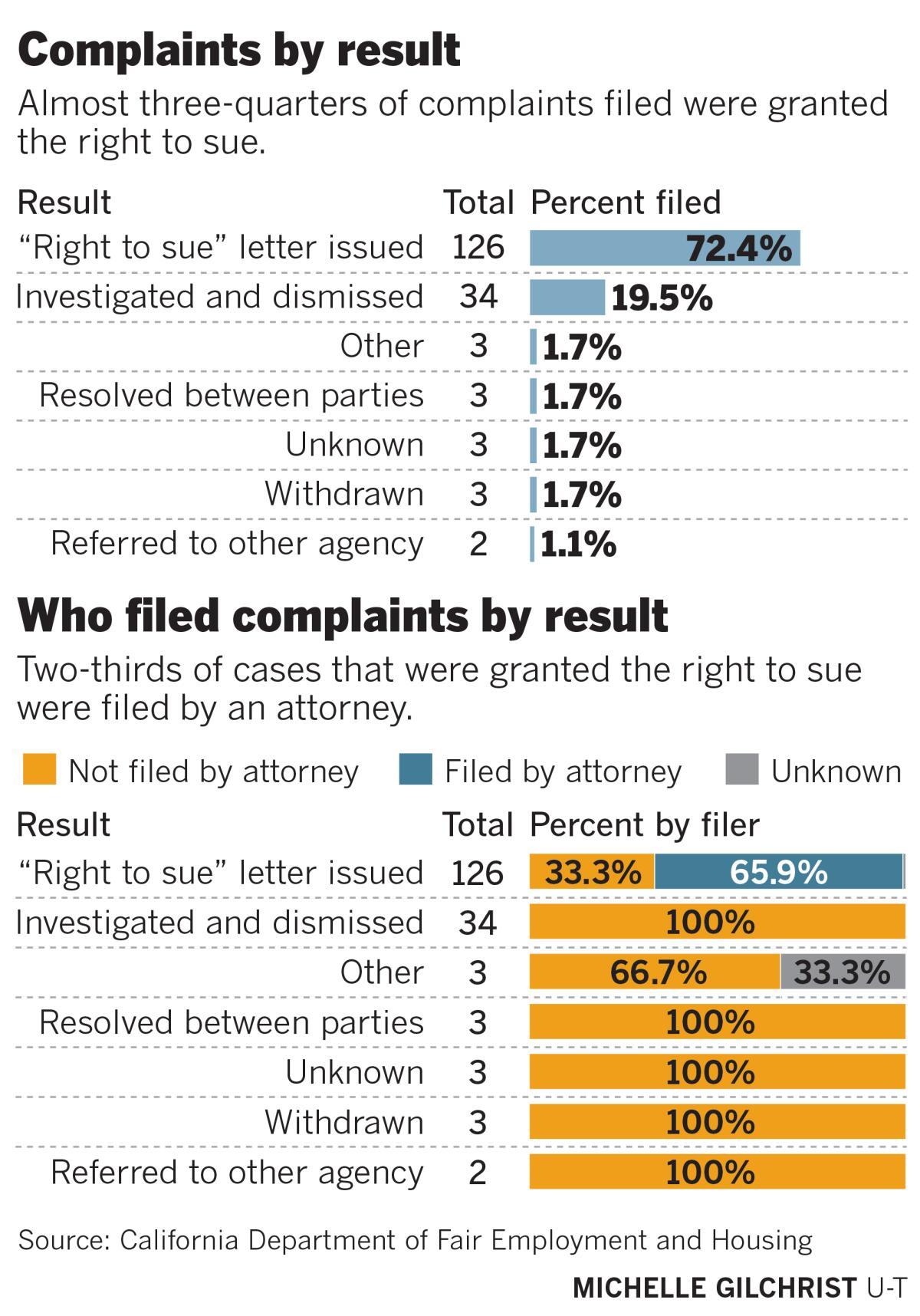

Out of nearly 200 claims filed against some of the region’s largest employers that the Union-Tribune reviewed, less than 1 in 5 were dismissed for insufficient evidence, though state data show having an attorney to help navigate the process improves an employee’s outcome. None of the claims filed by a lawyer was dismissed, and all 34 rejected cases were filed by the individual complainant.

Data show more than 70 percent of complainants were issued what is known as a “right to sue” letter, which employees need to pursue their case in court. Labor lawyers noted that getting a right-to-sue letter isn’t an assurance that the facts presented are correct, or that a case will win in court.

Nearly 30 percent of the claims reviewed by the Union-Tribune were filed against the city of San Diego or a city employee, more than any other entity. The city has some 11,600 employees on its payroll, representing about 7 percent of the total workers employed at the 11 public and private entities included in the Union-Tribune’s analysis.

Claims against the San Diego Unified School District, which has nearly 14,000 employees, accounted for about 17 percent of the total, the second-highest. Scripps Health was the target of 13 percent of the claims, and San Diego County was fourth with 11 percent.

San Diego city spokesman Jose Ysea said the city takes sexual harassment and discriminatory behavior seriously and provides training to all employees to prevent abuses.

“Every city employee is required to take sexual harassment training upon hire, as well as every two years,” Ysea said in an email. “Employees are trained on how to identify and prevent sexual harassment, bullying, retaliation and other forms of harassment and discriminatory behavior.”

The city also has multiple policies that prohibit sexual harassment and discrimination, he said, and employees have multiple ways to report it.

“Employees are encouraged to report issues to their supervisor or other member of their department’s chain of command,” he said.

City employees can also report issues to the Equal Employment Investigation Office, file a complaint with the city’s fraud hotline or reach out to their union representative, Ysea said.

‘Special friend’

Even so, claim records indicate many workers attempted to address their grievances through supervisors or human resource departments but little was done to address the behavior.

One woman who filed a claim against the city of San Diego in 2017 alleged she was subjected to “severe, pervasive and unwelcome and unwanted sexual comments, sexual innuendos and sexual advances” at the hands of her co-worker, the claim said. The woman’s name was redacted from state documents.

The conduct included sexual gestures at work, derogatory statements and graphic comments about the woman’s body. Several times the coworker texted the woman about his unhappy marriage, used emojis to say he was eyeing her butt, and said he wanted her to be his “special friend” and “replace his wife,” according to the claim.

“On one occasion, in front of male colleagues, (the co-worker) began to describe what he believed the complainant’s genitalia looked like,” the claim says. He would also describe the size of his genitalia and, at one point, exposed his bare backside to the female employee.

According to the complaint, the woman said she repeatedly declined the sexual advances and reported the inappropriate behavior to her superiors, who did nothing to stop the behavior, she said. Eventually she requested a job transfer.

The woman was granted a right to sue letter. The Union-Tribune contacted the attorney who filed the claim but the lawyer declined to comment.

Another claim filed in 2018 by a San Diego Parks and Recreation Department employee describes a similar series of events.

According to that complaint, a female worker was persistently sexually harassed by her boss. She said on several occasions he reached down toward her legs as she was sitting at a desk; he also allegedly lurked behind her and pressed his body against hers without consent.

The supervisor “repeatedly made inappropriate sexual comments to (the) complainant, such as asking ’Why do you keep staring at the pool table? Is it ‘cause you like balls?’ or telling (the) complainant that he wanted to see her midriff while she was leading volleyball practice,” the claim said.

The female worker repeatedly challenged the comments and stated they were unwelcome, but the harassment continued.

When she reported the behavior to other supervisors, they failed to take action, the claim said. Instead, she was retaliated against for making the complaints and forced to work in isolation.

Ysea said the city cannot comment on any specific personnel matters or ongoing litigation.

Workplace retaliation

The Union-Tribune’s review of the claims found that more than half of the workers were denied career advancements, or were transferred, demoted or terminated. In some cases, claims indicate such actions were only taken after the alleged misconduct was reported.

Some workers said they were suspended or laid off while their employer investigated their claims of abuse and were never reinstated. Others said they were reprimanded, bullied, forced to quit or had poor work reviews added to their personnel file after coming forward.

In one claim from 2018, Karen Sweetland said she was continually passed over for promotions and leadership positions at Qualcomm because of her gender. She said she spent years trying to address the discrimination through proper channels but was ultimately fired.

Sweetland started at Qualcomm in 2011 and, for several months, she worked closely with a colleague named Joel Mooney. Mooney later moved out-of-state, but, before leaving, he confessed that he had feelings for Sweetland. Her claim said she rebuffed his advances.

Mooney returned to San Diego the following year and became Sweetland’s supervisor. The claim accused Mooney of regularly belittling Sweetland with comments like “You’re worthless” and “No one wants you here.” He also told her that her “vagina is alienating people,” the claim said.

Sweetland said in her complaint that she believed the abuses were motivated, in part, by her earlier decision to reject his advances.

Qualcomm opened an investigation, and Mooney stepped down from leadership, but it was Sweetland who was forced to change departments, the claim stated.

Later, when Sweetland was applying for a job in leadership, another male supervisor, Alex Ahmadian, told her she would not be considered because “husbands and wives are good at different things,” the claim said. “Some people are better at feelings and others are better at executing.”

While applying for yet another leadership position, Sweetland asked for specific goals she should be working to achieve to be promoted. According to the claim, supervisor Jeremy Faraci told her to “keep doing what you’re doing.”

When she didn’t get the job, Faraci told her there were “invisible goals” that she should have been aware of and didn’t meet, the claim said.

Over the years, Sweetland repeatedly brought her concerns to Qualcomm’s human resource department, according to the claim. In 2017, she was fired. She was told that her position was being eliminated, but a job listing for her previous position was published later that month, the claim alleged.

Her case was settled, but the details are confidential.

In a recent interview, Mooney denied Sweetland’s allegations against him, saying that it was his “direct and to-the-point” leadership style that caused problems between them. He added, however, that he felt Qualcomm consistently mistreated Sweetland over the course of her career, and that the tech company often mistreated its employees, especially women and people of color, he said.

Qualcomm did not respond to several requests for comment about the allegations or its policies for responding to harassment reports. In legal documents, the tech company stated Sweetland was not able to demonstrate that it was her gender that prevented her from being promoted and that several other allegations fell outside the statute of limitations.

Ahmadian and Faraci did not respond to requests for comment.

Imbalance of power

According to a claim filed in December 2015, a parking enforcement officer with the city of San Diego was repeatedly discriminated against due to his age and medical condition, which required him to stay hydrated to avoid severe illness.

The claim says the worker’s supervisor would regularly rant “about needing some young bucks who can work fast.” The manager also expressed frustration when the worker would use the restroom during his enforcement routes, which often lasted three to six hours.

The boss knew about the man’s medical condition, as did the union, the claim said, but the employee was repeatedly threatened with punishment if he stopped to use the bathroom.

“As a result of being tormented for using the restroom, and fearing he would lose his job, (the claimant) was forced to urinate in his pants, rather than stop to use the restroom during his routes,” the claim said.

State records show he was issued a “right to sue” by DFEH officials, but it’s unclear if the man ever pursued legal action. The attorney who filed the claim on his behalf did not respond to requests for comment.

Even when workers argue and win their case in court, they can be left feeling exhausted by a process that can be belittling and intimidating.

LaFoy, the Sheriff’s Department secretary who won her case against the former assistant sheriff, said she is still processing her years-long fight for justice.

“You just feel so isolated and alone,” she said in a recent interview. “It was a very difficult situation to understand. I was the one asking for help, but I didn’t feel like they were helping me. They were continuing to keep me silent.”

LaFoy said she struggled at times in no small part because her employer minimized her experience and there was little transparency or effort to make her feel safe in her work environment. She worked at the department throughout the investigation and trial.

“My mission, ultimately, was holding the department accountable for the Assistant Sheriff’s sexual harassment,” LaFoy said.

At least one other woman filed a suit against Miller and the department. Her case settled in 2019.

After LaFoy’s verdict, the Sheriff’s Department issued a statement that it “does not tolerate sexual harassment of any kind and thoroughly investigates all reported or observed allegations.”

“We have clear policies that prohibit all forms of workplace harassment and we request our employees to immediately report any such conduct,” the statement said in part.

Many of the lawyers who specialize in employment law say cases often boil down to an imbalance in power. While it can be a difficult path, taking employers to court is one of the only ways to hold workplaces accountable, they say.

“Why should anyone get a pass for this kind of behavior,” asked Jenna Rangel, one of the attorneys who represented LaFoy. “I don’t care how big or small someone’s inappropriate conduct is. I think that they need to be held accountable for that. Because if you let people get away with things, eventually the line will be crossed again.”

The DFEH removed names, job titles and personal information from claim records that were released under the state’s open-records law.

The Union-Tribune attempted to identify complainants by contacting attorneys, reviewing staff directories and cross-referencing plaintiffs in San Diego Superior Court cases with those employed at the time by the agencies under review.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.