From Prison To Campus: These California Colleges Want To Ease The Culture Shock For Ex-Offenders

Navigating the challenges that come with the first year of college is tough for most students. For Robert Villanueva, a freshman at Pasadena City College, it was doubly difficult.

"I'm 36. You know, I have tattoos. I was kind of like nervous, I guess. I felt like I was out of place," he said.

That's because earlier in the year, Villanueva was released from prison after serving six years on a drug trafficking conviction. He said it's a culture shock to go from prisons like Folsom and Soledad to a classroom full of college students, many fresh out of high school.

But Villanueva found it easier to make the transition because Pasadena City College is one of about 30 community college campuses in California where faculty and administrators have stepped forward to create programs to help formerly incarcerated students.

THE FIRST YEAR IS CRITICAL

California community college students as a whole face significant challenges -- research shows that 70% fail to graduate or transfer to four-year schools. Formerly incarcerated students face additional obstacles. Many have problems with reading and writing as well as trouble finding work and a place to live because landlords and employers use criminal records to turn down applications.

Villanueva lived in a drug treatment center for six months after his release. That's where he learned some of the skills that have helped him overcome roadblocks during his first year in college. He learned how to identify healthy communication, how to ask for help, and how to unlearn much of how he was raised.

"Because in my culture, being Mexican, you know, as a kid you're taught that boys don't cry. So how do you process your thoughts and your emotions? So you suck it up... men don't cry," he said.

He's taking psychology and sociology classes and wants to become a counselor who helps people like himself in adapting from prisons to life outside, where making decisions and choices denied to inmates every day can be overwhelming.

Counselors say formerly incarcerated students are more prone to feeling lost.

"I think that a lot of times it comes down to not being able to navigate these challenges because they don't have the support systems," said Anne-Marie Beck, a counselor at Glendale College. "They don't know where to go on campus and who to talk to, and they don't want to out themselves either, because they feel such a sense of shame about their felony conviction."

At Glendale College, 15% of community college students who enrolled in the fall of 2011 didn't return for their second year. Beck says the dropout rate is lower for formerly incarcerated students who seek out help.

Glendale College offers that kind of help by providing access to social service agencies that can help with jobs and housing, faculty mentorship, and guidance from formerly incarcerated students farther along in their education.

With state and local funding, Glendale College started something new this academic year for its formerly incarcerated students and those from surrounding campuses: a monthly campus meeting for students and representatives from nonprofit agencies.

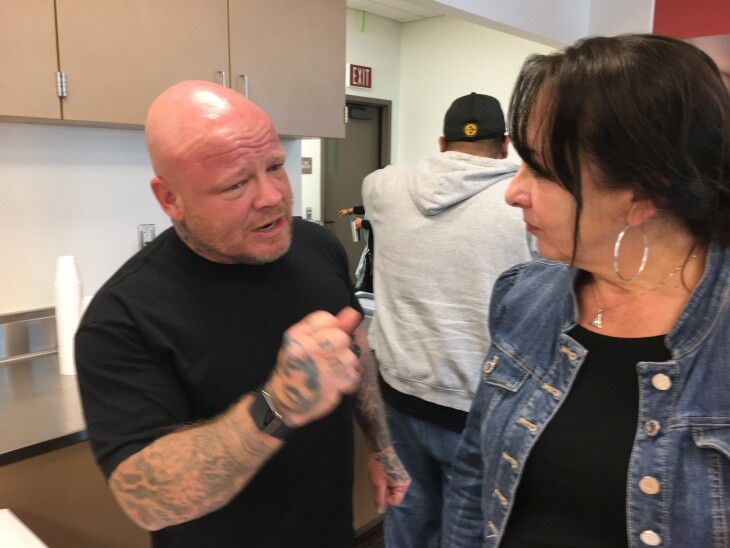

This month's meeting featured Danny Lansdale, a motivational speaker who started Standing United, a nonprofit to help newly released ex-offenders get on their feet. He founded the organization after years of drug addiction and 15 years in prison.

"Today I'm also a counselor... a business owner, a good father, a good son," Lansdale told about two dozen people gathered in a campus conference room.

Villanueva was there and came away impressed.

"You gotta learn how to trust the process, and not the people, because people always let you down, but not the process," he said.

Glendale College administrators have also started going to probation offices to describe available support services to recently released ex-offenders.

"I help them through the entire process of applying... to school, registering for classes, applying for financial aid," said Glendale student Travis Leach, who spent years in and out of jail while addicted to meth. Leach is transferring to California State University, Los Angeles in the fall to earn his bachelor's degree in social work.

FUNDING A STATEWIDE MOVEMENT

In April, the chancellor's office releaseda list of community college campuses that will receive $113,636 each to fund programs to help students with criminal records.

"I wouldn't be surprised if another 10 or 20 arise in the next year," said Debbie Mukamal, a Stanford University researcher specializing in education for formerly incarcerated students.

The state is also growing its community college instruction inside California's prison system. About 4,000 inmates were enrolled in classes in Spring 2018 offered by 19 community colleges.

Administrators say taking classes while incarcerated gives the inmates a head start if they decide to enroll in community colleges when they're released.

A report released earlier this year found that 85 percent of inmates taking the classes pass them -- that's 10 percentage points higher than the overall pass rate for California community colleges.

DON'T CALL THEM EX-CONS

"I think there's been a lot more appreciation for the importance of doing what we can to remove the stigma that's associated with having a criminal record," Mukamal said. Part of removing that stigma is avoiding labels like ex-felon, ex-convict, ex-offender or ex-prisoner because the underlying idea is that their time in prison is more important than them being people first.

Her preferred descriptions are "person with a criminal record" and "student with a criminal record."

Villanueva describes himself as "formerly incarcerated." He likes the term because it communicates that he's out of prison, that he's "out of the box," and working to create a new life for himself.

-

The hundreds of thousands of students across 23 campuses won't have classes.

-

Over 100 students from Cal Poly Pomona and Cal Poly San Luis Obispo learned life-changing lessons (and maybe even burnished their career prospects).

-

The lawsuit was announced Monday by State Attorney General Rob Bonta.

-

Say goodbye to the old FAFSA and hello to what we all hope is a simpler, friendlier version.

-

The union that represents school support staff in Los Angeles Unified School District has reached a tentative agreement with district leadership to increase wages by 30% and provide health care to more members.

-

Pressed by the state legislature, the California State University system is making it easier for students who want to transfer in from community colleges.