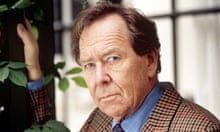

For all his other accomplishments, as a photographer, film-maker, designer and champion of disabled people, Lord Snowdon, who has died aged 86, will be chiefly remembered as the commoner who married a princess. When, on 6 May 1960, the then Antony Armstrong-Jones married Princess Margaret, Queen Elizabeth II’s younger sister, he became the first non-aristocrat to marry into the royal family for 400 years; when they divorced 18 years later that set a modern precedent, too.

There was considerable public excitement that the princess, wayward, beautiful and previously unlucky in love, was to marry Armstrong-Jones, someone not only outside the usual milieu and not even from the ranks of the professions, but a society photographer.

In fact, Armstrong-Jones was by no means a parvenu. He came from the Welsh gentry, the son of a barrister and a society hostess. Having been educated at Eton and Cambridge, he was making his living as a portrait photographer of the rich and famous.

Nevertheless, as the 1960s dawned, his liaison with the princess was an early sign of the relaxation of some at least of the protocols of the stuffy and hidebound royal court. Had the public – or the royal family – known how the marriage would develop and eventually disintegrate in a welter of vitriol and promiscuity on both sides, the crowds who thronged the Mall to celebrate the nuptials would have been considerably reduced and less starry-eyed. At that stage, public cynicism about the royal fairytale had yet to set in.

Antony, the second child and oldest son of Ronald Armstrong-Jones and his wife, Anne (nee Messel), was born in the fifth year of the couple’s marriage, at their home at Eaton Terrace in Belgravia, west London. The house had been the wedding gift of his mother’s father, a member of the Messel family: Oliver Messel, the theatre designer, was an uncle, and another ancestor was the Victorian artist and cartoonist Linley Sambourne.

The parents’ marriage was already breaking down as the boy was born, and collapsed acrimoniously within a year, with divorce following four years later, his mother subsequently moving to Ireland to marry the Earl of Rosse, and his father also remarrying and moving peripatetically between Wales and London. Antony and his sister found themselves shuttled between their feuding parents and, when with their mother, treated as distinctly inferior to the earl’s children. It was a loveless and emotionally starved childhood, exemplified when Antony contracted polio at the age of 16 in 1946 while on holiday in Wales and spent six months recuperating in Liverpool Royal Infirmary, unvisited by either parent. The illness left him with a permanent limp and, perhaps, a tendency to self-absorption.

It was unsurprising that he developed enthusiasms that were essentially solitary: a lifelong enthusiasm for gadgets and for photography, as well as a degree of emotional distance and wilfulness, often disguised by a coating of charm. In 1949, he went to Jesus College, Cambridge, to study architecture, but left after failing his exams, though only after coxing the university team to victory in the 1950 boat race.

Handsome, socially well-connected and ambitious, he set up as a photographer in London and started selling society and theatrical pictures – Laurence Olivier as Archie Rice was one – to magazines such as Tatler and Vogue, and to newspapers including the Daily Express. Eventually, invitations to take formal photographs of members of the royal family followed. His older rival Cecil Beaton, clearly feeling under threat from the young upstart, noted in his diary: “I don’t think AA Jones’s pictures are at all interesting, but his publicity value is terrific. It pays to be new in the field.” Unlike Beaton, AA Jones was also ostentatiously heterosexual and cut a swath through the debs and actresses of London society. “If it moves, he’ll have it,” was the word.

It was at one such photo session in 1958 that he met the young Princess Margaret, whose love life had been publicly thwarted three years earlier when she had been forced to abandon hopes of marriage to Group Captain Peter Townsend. The princess, unwillingly enduring the tedium of life at court – though she never objected to the privileges of royalty – was intrigued by the photographer’s relative lack of deference and his dashing willingness to whisk her anonymously down to his hideaway in Rotherhithe, south-east London, for clandestine evenings away from the palace. He charmed the Queen Mother and also won over her older sister, whose permission, as Queen since 1952, she needed to marry.

When it came, the wedding in Westminster Abbey was – not unlike the similarly ill-fated royal wedding 21 years later, between Charles and Diana – an occasion of great public celebration, televised and rounded off with balcony appearances before the crowds outside Buckingham Palace. Only a few people privately forecast problems. Noël Coward, who knew both parties, wrote in his diary: “He looks quite pretty but whether or not the marriage is entirely suitable remains to be seen.” The comptroller of the royal household bade farewell to the headstrong princess on her way to the abbey with “Goodbye, your royal highness,” adding under his breath: “And we hope for ever.”

Unnoticed, as the newly-weds celebrated their honeymoon on board the royal yacht Britannia, cruising the Caribbean, Camilla Fry, the wife of the bridegroom’s oldest friend, gave birth to a daughter. Only 44 years later did Polly Higson discover through a DNA test what society rumour had long alleged, that Armstrong-Jones was her father.

The couple returned to a stultifying life at court with minor official engagements, during which husband had to walk always several paces behind wife. He was part of the royal family and yet not royal, routinely sneered at and ignored by the servants who were resentful of his ambiguous position within the household.

In 1961 there was the consolation of ennoblement for Armstrong-Jones, henceforward known as the Earl of Snowdon in a nod towards his Welsh roots. Such was the deference of the day that when his effigy had been stolen from Madame Tussauds and placed in a telephone box the year before, members of the public who found it did not dare open the door in case they were intruding on a private call.

At formal dinners the princess was served first, bolting her food in the knowledge that none could continue eating after she had finished, nor leave before she did (when interested, she could stay into the early hours, when not, she could be staggeringly rude to both hosts and servants). At informal gatherings, the couple could listen to the Queen Mother’s prejudices about television programmes. Entertaining friends, such as Peter Sellers and his wife, Britt Ekland, at the royal apartment in Kensington Palace was a constant diversion. As, more intermittently, were their two children: a son, David, now Viscount Linley, born in 1961, and a daughter, Lady Sarah Armstrong-Jones (later Lady Sarah Chatto), born in 1964.

Snowdon sought to escape the royal routine with work, acquiring a contract for photographic assignments with the Sunday Times. It was an engagement that would last for nearly 30 years and would encompass a wide range of work for the paper’s magazine: not just celebrity portraits but startlingly original and empathetic documentary photos on issues such as poverty, disability and deprivation. That empathy was most vividly revealed in 1966 when he rushed, well in advance of the dictates of royal protocol, to comfort the relatives of victims of the Aberfan disaster, sitting with bereaved parents and making them cups of tea over several days after a slipping coal slurry tip engulfed the South Wales village school.

His design skills were used in the construction of the striking 1960s aviary at London Zoo and, later in the decade, in organising the investiture of Prince Charles as Prince of Wales at a ceremony in Caernarvon Castle, beneath a large and sweeping transparent awning, in July 1969. Snowdon could scarcely take his wife with him on assignments, and the couple drifted apart as he spent increasing periods away, often with a succession of female assistants and other lady friends. He seldom rang home. The princess herself took lovers during his absences. One of Snowdon’s closest friends was astonished to be propositioned one evening at dinner. “Let’s go to bed,” Margaret said suddenly. When he demurred, she edged closer and pouted: “Well, I think you could be a bit more cuddly.”

The estrangement started quite early and erupted into increasingly public spats, sometimes fuelled by alcohol and drugs on the princess’s part. When Snowdon made a documentary about dwarfism in 1971, the princess, acutely conscious of her short stature, took it as a personal slight.

At parties, he would cut her off in mid-conversation. “Shut up and let someone intelligent talk,” was one such sally. Another note, from husband to wife, apparently read: “You look like a Jewish manicurist and I hate you.” The royal family, well knowing the princess’s tantrums, tended to take his side.

The couple, having lived increasingly separate lives, parted in the mid-70s and were formally divorced in 1978. Margaret floated off into a largely empty life with unsuitable lovers such as the playboy Roddy Llewellyn and long holidays on Mustique, until a series of strokes precipitated her death in February 2002.

Snowdon himself was married again, almost immediately, to Lucy Lindsay-Hogg, the daughter of an Irish businessman and former wife of the film director Michael Lindsay-Hogg. She had formerly been one of his assistants, and the pair had conducted an affair for several years. Their daughter, Lady Frances Armstrong-Jones, was born seven months after their wedding. The marriage eventually foundered in 2000 after his wife grew tired of his serial adultery – one affair was with the Guardian journalist Ann Hills, who in 1997 took her own life. It had become clear that the elderly peer had fathered a child with his latest friend, Melanie Cable-Alexander, half his age, an editor on Country Life. That liaison produced a son, Jasper Cable-Alexander, in 1998.

And there were other relationships, with the charity campaigner Marjorie Wallace and Emmy Hirst, who also eventually fell out with him. Snowdon’s biographer, Anne de Courcy, relates a trip to Russia by Snowdon and Hirst for Christmas 2004: “She had the embarrassing task of ringing the hotel management to say: ‘Lord Snowdon wants the adult television channel.’ In Britain such a choice would quite likely have made all the gossip columns, but in St Petersburg it passed unnoticed, a small example of a general lack of recognition that depressed him.”

Snowdon continued with his photography, working for the Daily Telegraph (1990-94) until his contract was terminated for being too expensive, and with his design work – a wooden wheelchair was one project. He also served on charities and, from 1995 to 2003, was provost of the Royal College of Art. He maintained his links with the royal family – taking the Queen’s official 80th-birthday portrait – and, as part of what had always been an eclectic portfolio, the result of a driven nature and a need for cash, even photographed the winners of one of the Big Brother TV series. In 1999, Snowdon was given a life peerage as Baron Armstrong-Jones, of Nymans – named after the Sussex village where he kept a country home for many years – to enable him to continue sitting in the Lords.

De Courcy said of his marriage to Princess Margaret: “They were icons of the 60s, in the vanguard of all that was new and exciting, effortlessly mingling the arts and the establishment ... Long before Buckingham Palace entertained them, writers, painters, journalists and dancers poured through the doors of Kensington Palace.” In so many ways, beyond the glittering lifestyle and celebrity guest list, the marriage for which Snowdon will be remembered, which took him into the heart of the royal family, was a dreadful harbinger of what was to come.

He is survived by his children.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion