The seventh stage of the USA Pro Cycling Challenge on Sunday in Denver is Jens Voigt’s final bike race. The outspoken German, who at 42 is currently the oldest racer in the pro peloton, is hanging up his bike after 33 years of racing, 14 of them as a professional.

Jens Voigt

Jens VoigtVoigt has ridden countless races, including 17 Tour de Frances (with finishes at 14) and three Giro d’Italias, and notched stage wins at both the grand tours. But he’s probably best loved for his willingness to attack, like the day he won Stage 4 of the 2012 USAPC, as well as his quick wit and pithy one-liners. His zinger in an interview, “Shut up, legs!” has been printed on T-shirts and race roads around the world.

We caught up with Voigt in Aspen a few hours before he lined up for stage one of his final race. He was chipper, funny, and forthright as ever, and said that he was looking forward to retirement.

OUTSIDE: Why did you choose to end your career here at the USAPC?

Voigt: Last December, when we were planning the year, I told the team, “Listen, I know I have one more year contract, and I know it’s going to be my last year. Call me stupid but I don’t count myself out for the Tour de France team. I know I am 42, but I am training, I am planning the season so I can be ready for the Tour de France..

Going into my last season, I didn’t want to have two easy races then finish after the Tour of California in May. I get paid for 12 months, so I wanted to work for more than two months.

I believe I am allowed to say this, but I think I have a good fan base here in the US. So after the Tour, it felt only natural to stop here. Generally speaking, we normally have some good weather in Colorado. And there’s a beautiful landscape. Imagine you finish your last race in somewhere in a lost corner of Europe, and it’s raining and small roads and crashing and stressing. I didn’t want that. It’s just nice here. It’s a good way to finish.

Has it been a difficult last season? Do you feel the age?

I feel the age clearly on fast downhills. I just think more, I reflect more, I brake more. I was never the craziest descender, but 15 years ago I would take as much speed as I could get. Then there were years when you go, “Why don’t we just stay at 60 miles an hour?” And nowadays, I think, “Why don’t we just stay at 50 miles an hour? Isn’t that fast enough?”

The suffering is still good. The body, the engine, so to speak, it’s still there. But I’m missing the kids and the family more. I realize more now that I’m missing part of their childhood.

Only in the last two years in the Tour have I had these moments where I go, “Hmm, can I reach Paris? Oh, I don’t know about that.” Before that, I had 15 years where I thought, “Of course I go to Paris. Of course there is no problem.” So even though it might sound a little arrogant in your eyes, I only realize now what a rider I was in my best days. I realize how good I was back then.

I really successfully pushed the aging process back for a very long time. But it has to come one day. It’s simply the way that nature goes.

What do you think has made you so popular with the American public?

Simplicity. Loyalty. Reliability. Humor. Hardworking. That’s the essence.

I think one of the keys that I have so many fans, apart from the fact that I can ride my bike fast and I can suffer a lot, I’m just the most normal person on earth. I have six children. I raise them with my wife. We don’t have any nannies or gardeners or a pool boy. I pay my taxes in Germany, and I’m okay with it because it’s a beautiful country and I want it to keep like that. I don’t avoid it by moving to Monaco or Switzerland. I have a dog, and I walk the dog. I have rabbits, and I clean the rabbit cage myself. I mow my own lawn.

I am just the most normal person on earth, and I think the fans like that.

Americans also like your panache, the fact that you’re willing to go out on a break all day and attack. Where did you get that trait?

Early in my career, at some of my first races, I realized that attacking is just my nature. I am a person that acts instead of reacts. It’s the same with a lot of things in life. If you come to a room where nobody knows anybody else, instead of having an embarrassing silence, I just break the silence and chat up the first person next to me. It’s the same in cycling. I like to make things happen.

My early races, as a child, I had some success with it, so you get the positive reinforcement in your brain: Attack, success. And after you have that two three times, you just go, “Yeah I think that’s the way to go.”

And you have to be realistic, to realize, “Okay, I don’t have enough fast fibers to be Marcel Kittel [one of the world’s best sprinters]. And I’m way too big to be, for example, Nairo Quintana [the Colombian climber who won this year’s Giro d’Italia].” So then you have to realize what do I have and what can I do with it?

All I have is my desire to win and my big engine. I can go very hard. I can suffer for a very long time. And so for many years, whatever made the race hard was good for me. It’s maybe not the most effective way to win anything. But that’s just what I could do, so I had to work with it.

Does the futility of the breakaway ever weigh you down? Do you think, “Oh there’s no sense in attacking. I’ll just get caught 200 meters from the line?”

If you are at the start line with 200 riders, and you are not going to try to attack or try to win, you’ve’ already lost. If you go out on attack, you have maybe 10 percent chance. Maybe it’s five, maybe 15. But I’d rather take 10 percent than no chance at all. I would just feel like cattle, like a sheep, going to get butchered later by the sprinters or the climbers.

And even if you don’t win, it’s okay. I don’t think that too many people know that I won the Tour de Poitou Charentes twice. It’s a small stage race in France. The general public doesn’t know anything about that. But they know me for being out in the Tour de France and getting caught in the last minute.

People will always remember you for those dramatic breakaway wins. But when you look back on your career, how would you like to be remembered?

I want to be remembered as a good bike rider. Even with all the funny talk and the one-liners and the suicidal breakaways, I still managed to have 65 official UCI race wins. That’s a lot if you’re not a sprinter.

Some years ago we had a cobblestone stage in the Tour de France. And we worked hard with CSC to get our boys first in there. In the last pavé, at the front of the race, it was Fabian [Cancellara], Andy Schleck, Frank Schleck, and me. And somebody else from another team took the corner too quick, slid out the corner, and took Frankie out. And I was the first one standing there next to Frankie, asking him if he was okay. Maybe I could have won the stage or something. But I didn’t care. I stopped the bike. So I also would like to be remembered for my loyalty.

I don’t think I have any tricky wins. All of my wins, I earned, I worked for. It’s not like I flicked somebody in the last minute. So yeah, I was a good rider, but also I was an honest and loyal one.

What do you consider the landmark moment in your career?

I won my very first race, a hilltop time trial. That was pretty cool. It was in 1981, and in East Germany, we didn’t even have a phone at that time. I was the youngest kid in the group, so I started at 10 a.m., and the race then was going on until 2 p.m. or 3 p.m.. When I realized I’d won, I couldn’t even tell my parents. There was no phone or Internet. Nothing. The team had to drive home three hours. So it wasn’t ‘till 8 p.m. at night that I could even tell my parents I’d won the race.

What about the most memorable moment in your career?

In a negative way, it was the loss of our teammate Wouter Weylandt. He crashed in the Giro d’Italia and lost his life. He had a pregnant girlfriend at the time, so his daughter was born never seeing her father. That was the hardest thing I ever had to get over in my career. It made you question racing.

On the good side, I loved to win the Tour de France in 2008. We had Carlos Sastre in yellow. We won the team GC. We had this beautiful picture with all of us on the Champs Élysées, the Arc de Triomphe as background, beautiful sunshine. It was just a million-dollar picture. That win was Sastre’s win, but it was also a win for all of us.

What’s next?

I am going to be working with the team next year a little bit. I’ll be doing some events with Trek Travel. I have this book that I am going to finish writing. Hopefully I’ll still do my online column. I’ll probably develop my product line. I think I’m going to do some commentating. Now it’s a question of doing a bunch of different things so I can find out what I like, what I’m good at, and what I want to do for the next five or ten years.

Do you consider leaving the cycling industry?

Sometimes you are tempted to not only close the chapter of cycling, but close the whole book and open another one. But whatever I would do outside of cycling, I would only be second best at the start. I would have to learn and start from zero. So it’s just logical, reasonable, to stay in cycling. It would be a waste to throw away all of my experience and all the lessons I learned in life.

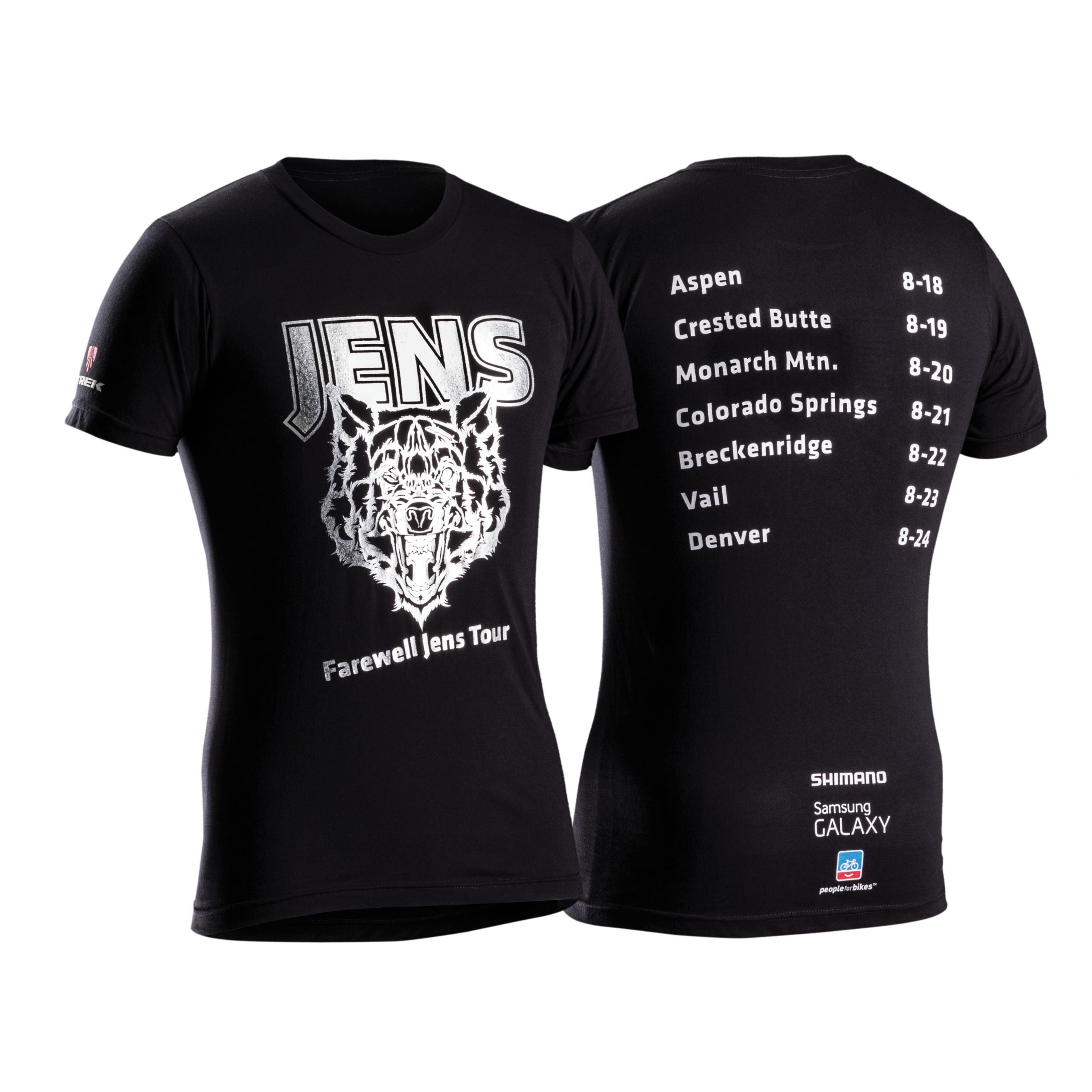

Trek has made limited edition bikes (you can even enter to win one during the USAPC) and gear for your retirement. What’s the scoop with the wolf on the t-shirt?

I read a lot, and I’ve always liked Rudyard Kipling. In the Jungle Book, there’s the old alpha wolf, Akela. And he actually helps Mowgli come into the tribe. Without getting too philosophical, Akela is an open-minded, modern personality. There’s all these wolves, and they discuss if they can have this human being in the tribe. And of course there’s racism, and the wolves go, “He’s not one of us. We don’t want him.” And Akela speaks out for the little child and helps it to survive. In the end, Akela goes down in this terrible fight.

I felt connected to this character. He had a responsible position, but he was still open to new things. And he went down fighting in the end, protecting his tribe.

It’s an old, scarred wolf. He lost one eye. He lost some teeth. That’s me. I’m not beautiful anymore. I’ve got scars everywhere. I still have two titanium pieces in my body. The other day I counted, I think it’s something between 110 and 120 stitches I’ve had, in my face, in both of my elbows, hips, knees. I feel like the old wolf that’s been marked by my life in cycling.

Will you miss bike racing?

I should say, “No, of course not.” [Jens laughs.]

But yes, 33 years of cycling, that’s the longest consistent thing in my life. How can I not miss it a little bit? My life has been surrounded by cycling all these years. Wake up, take the kids to school, come home, and go training. Then in the afternoon, I have to fix the bike, I have to wash the bike. So it will be a big change with all of this gone.

The racing is still awesome. But the five hours a day of intervals, it’s extremely hard now. I don’t want to think about training, training, training anymore. So I am not going to miss that. I believe that I squeezed everything out of my body. I want to embrace life a little more. I want life to be easier. I don’t want to be restricted. I don’t want to eat muesli anymore. Instead of having muesli in the morning, maybe for the first week I will have five fried eggs every day with sausage.

Is there anything you’ll miss?

I’m not going to miss the suffering and the traveling. But I will miss the feeling that I’m strong, that I’m healthy. It crosses my mind five times a day: From now on I am getting older and slower and weaker. And fatter probably.

But it sounds like you’ll be happier?

Definitely happier. More relaxed, yeah. That’s also one thing I am not going to miss: being forced to eat rice and pasta in the morning. What the heck? I am so over that.