Jayne Wrightsman's Jewelry Collection Was the Stuff of Legend

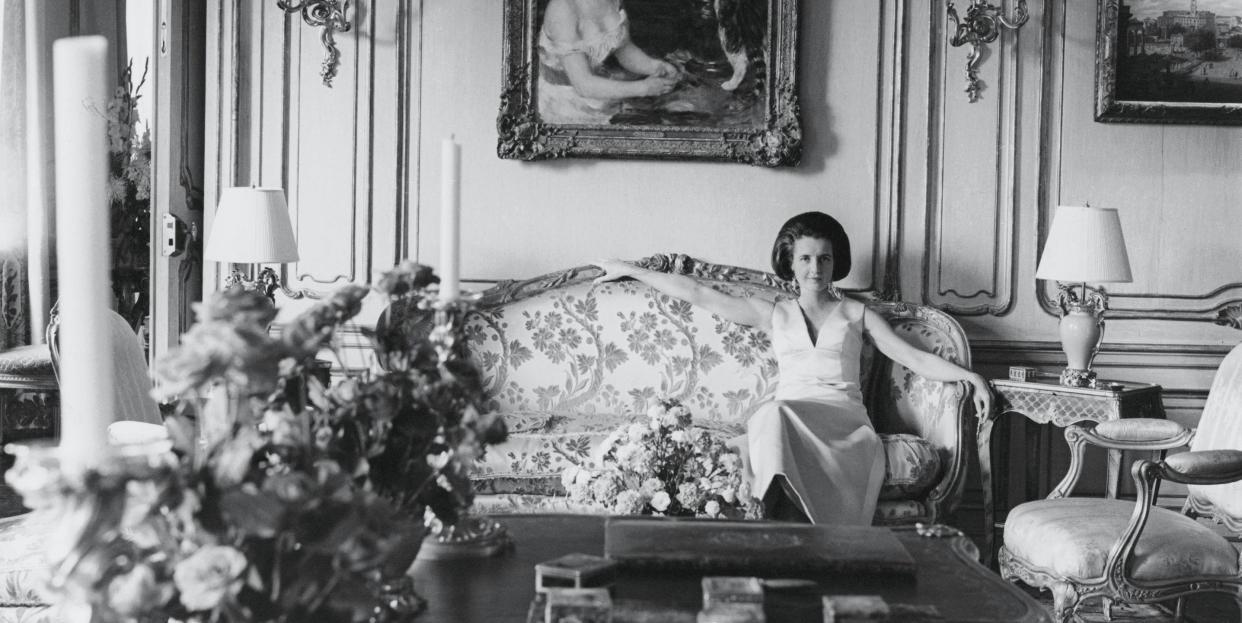

When philanthropist and socialite Jayne Wrightsman died last Saturday at the age of 99, she was rightly lauded for her impeccable eye for fine art and antiques. Starting in the 1950s, she and her late husband, former Standard Oil of Kansas president Charles Wrightsman, studied, purchased, and lived with rare paintings by European masters and exquisite pieces of 18th-century French furniture and decorative art, many of which they ultimately donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Less known is the fact that Jayne was a connoisseur of fine jewelry, and her possessions the subject of fevered speculation. She and her husband were such private people-they rarely spoke publicly or gave interviews-that no one knew exactly the pieces in her collection, just that they were of the highest caliber.

In 2012, Sotheby’s auctioned some of Wrightsman’s jewelry with pieces from the collection of Estée Lauder, and the total of the combined sale was $64 million, a then one-day record for the auction house.

“They complemented each other,” says Catharine Becket, head of Sotheby’s Magnificent Jewels Auctions in New York. “Mrs. Wrightsman was a great connoisseur, so her collection was very much design-driven. In the Lauder collection, there was a heavy emphasis on important gemstones.”

Although Wrightsman had an excellent sense for what would appreciate in value, she bought jewelry primarily to wear. “I think she comes out of the Duchess of Windsor mold in that sense,” says Becket, referring to the late Wallis Simpson. “Her clothes, which were incredibly well tailored, served as a blank canvas on which to hang jewels.”

The auction featured 60 items from Wrightsman’s collection, including pieces by Cartier, Verdura, and JAR. “What really struck me about her taste was how educated it was while not being overly academic,” Becket says. Two works in particular demonstrate the nuance of her selections, a 17th-century emerald rosary and a Cartier “Arab Sautoir” necklace, inspired by traditional Islamic prayer beads. “Everything was beautiful, but she had broad cultural interests.”

Wrightsman developed close relationships with many top jewelers and collaborated with some on pieces they made for her. “Verdura, in particular, would make tweaks to things at her request,” says Becket. “Most people would never dream of asking him to change anything, but she was ultimate taste maker.”

When buying art and antiques, Wrightsman was interested in provenance and culturally significant moments (she kept Marie Antoinette’s last diary on a table in her apartment in New York) and the same held true for jewelry.

One example from the auction was a 19th-century diamond bow brooch that once belonged to the Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia and her daughter Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent, who wore it to the coronations of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth II. “History had great meaning for [Wrightsman]," Becket says. "The piece is beautiful, but it takes on importance because of its connection to the Russian imperial court and then the British aristocracy.”

The bow sold for $842,000, almost three times its high estimate. Here again, provenance may have had a role. “For people who know jewelry, Wrightsman’s name certainly means a lot," Becket says. "If you're acquiring a piece that she selected, it gives you reassurance that you're choosing well.”

('You Might Also Like',)