Bernard Shaw famously compared Richard III to a Punch and Judy show. “Richard,” he wrote, “is the prince of Punches, he delights Man by provoking God.” In Thomas Ostermeier’s production for Berlin’s Schaubühne theatre, the actor Lars Eidinger is a distinctly puppet-like Richard. He has a gleeful energy, a skull-hugging leather cap, exaggerated knock knees and a hump that is clearly artificial (as is plain to see when he strips naked to woo and win Anne, the widow whose husband he has murdered).

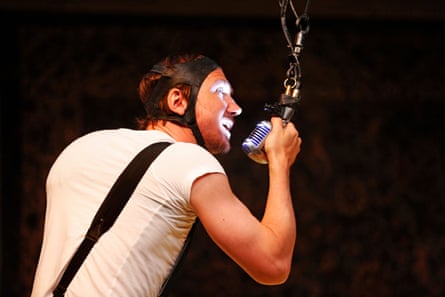

He develops a darkly humorous Mr Punch-like rapport with the audience: after throwing a plate of food at Buckingham (a finely wrought, nerve-exposing performance from Moritz Gottwald), he screams at him: “You look like shit!” and lollops off the stage into the auditorium to set up a panto-style call and response around the word “scheisse”. Having become the king, he is apparelled in a full body corset, neck brace, bare legs, white underpants, white-painted face and jerks about the stage like an automaton whose joints are rusting: flesh transmuting to thing.

In this portrait of Shakespeare’s most villainous villain, it is the thing-ness that dominates: we never see what forces motivate this Richard, nor what emotions move him to action. He is empty of humanity. This does not come across as an insight into the character’s isolation, but rather as an actor’s bravura solo turn (in spite of surrounding performances of clarity and precision).

In the final battle, Richard is alone on stage, sword-thrusting imaginary enemies. The relations between his actions and a world of political, social and emotional consequences are negated (an obliteration emphasised by the cutting of Elizabeth, Anne and Margaret’s pre-battle confrontation of Richard with his crimes, along with Anne’s curse that he will die on the battlefield). What remains is beautifully executed spectacle.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion