If you were a wrestling fan on May 23, 1999, you were probably doing one of three things. One of those was watching WWE’s latest pay-per-view event, Over the Edge. Another was using “scramblevision” to listen to that event by tuning a TV or VCR without a cable box to the pay-per-view channel. Some fans were probably also watching The Jesse Ventura Story on NBC, which they doubtless regretted instantly. The low-budget Ventura biopic, made with cooperation for WWE’s rival promotion WCW, was an absolute catastrophe of a film and a rushed, obvious cash-in on Ventura’s upset win in the Minnesota gubernatorial election six months earlier. While bad and stupid in every possible way, the movie’s most enduring artistic legacy is the absurd amount of “creative license” it took, most famously through making Ventura a central figure of a scenario that was clearly based on Bret Hart’s last night in WWE.

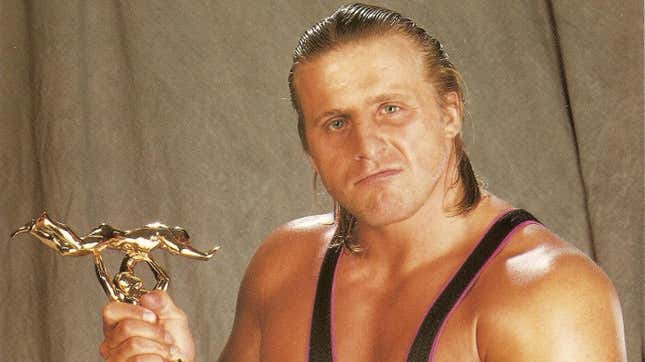

As the movie aired on the east coast and the pay-per-view was beamed from Kansas City, Bret Hart was flying to Los Angeles for what should have been a highlight of his career. He was slated to wrestle on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, but that never happened. “[T]he cockpit door opened and the pilot came out, and I just knew that he was looking for me,” Hart wrote in his memoir. “He handed me a note that read, ‘Bret Hart, please call home. Family emergency!’” Heeding that advice got Hart nothing but busy signals, so he checked his voicemail, where he heard a frantic message from Carl De Marco, a Hart fan who later became his business manager, and who had since moved on to running WWE’s Canadian operations. Bret’s baby brother, Owen, was the lone Hart family member left in WWE; De Marco making such a call had obvious connotations. Bret tried every phone in first class to no avail until he found the only one that worked. De Marco answered right away and issued repeated “Are you sitting down?” warnings. Bret demanded that he “just spit it out.”

“Owen’s dead. He got killed doing some kind of stunt in the ring.”

All that anyone would learn that night was that Owen was set to rappel from the top of the arena, in his Blue Blazer character, to parody his WCW rival, Sting. Somehow, Hart’s harness was disconnected, and he fell to his death.

On the broadcast, viewers saw none of that. Owen fell while a video hyping his match was playing both in the arena and on TV, though the Spanish-language announcers’ microphones at ringside were open so they could translate; their horrified reactions to the actual fall were heard in real time. Viewers got only the most basic information; cameras showed the live fans, who, themselves, were never actually given any information. Once Hart was wheeled to the back and a waiting ambulance, the show picked up with the next scheduled match almost as if nothing had happened. The ring was visibly broken in the corner where Owen landed, and so the wrestlers avoided that section. The busted ring gave WWE plenty of cover to end the show, but they didn’t. Instead, Jeff Jarrett, Owen’s best friend in the company, was shoved out to do an interview alongside his valet, Debra. They then staged their scheduled match despite barely seeming on the verge of tears in their promo. An hour later, after Hart’s family was notified, the pay-per-view audience was told of Owen’s death.

The rest of the show was a bizarre approximation of “normal” staged by people who had been fundamentally broken. They were short a referee, as Jimmy Korderas, set to work The Blue Blazer’s match with The Godfather, was in the ring when Hart fell. Owen made light contact with him—albeit enough to cause a bump on his head—before crashing to the ring, and while Korderas was fine, he required a precautionary hospital visit. The show just went on without them, regardless of just how obvious it was that it shouldn’t have. Right before the main event, one camera caught the usually unflappable Undertaker on the verge of tears and staring sullenly at the broken corner of the ring.

“This is a stunt that’s performed on a routine basis in a number of venues,” WWE boss Vince McMahon explained at an impromptu press conference later that night, footage of which was excerpted in the Life and Death of Owen Hart documentary. “Owen was simply to descend into the ring in superhero-like fashion,” McMahon said. When a reporter asked why there was no backup line of any kind, as that would be the normal, expected way to do such a stunt, McMahon replied, “I’m not an expert in rigging; I guess you are.”

The reporter pressed on, saying that it still looked like there were “no precautionary measures,” which raised the ire of McMahon, who continued deflecting. “First of all, I resent your tone,” he non-answered. The reporter shot back, “I resent the sarcasm.”

“No, no, I resent your tone, lady, OK?” McMahon continued. “This is a tragic accident. This is a tragic accident. Don’t try and put yourself in the spotlight here, OK? This was an accident. Do you understand what I’m saying? An accident. And everything that should have taken place in terms of rigging, to our knowledge at this moment, did take place. It was rehearsed in the afternoon and everything was fine. That’s all I know.”

Even to wrestling fans without any time to do research, it did seem weird: How could this have happened? Sting’s regular descents to the ring in WCW were so laborious that the heels he faced often were stuck lingering uncomfortably while Sting unhooked himself after landing; how could WWE have been so reckless with the life of one of its stars in what was effectively a parody of that? A wrongful death lawsuit against the promotion was inevitable, and when it did come a few weeks later an already terrible situation quickly got even dirtier and uglier. Martha, Owen’s widow, found herself publicly sparring with WWE over such matters as the cost of her husband’s funeral and a clip of wrestlers mourning airing on Monday Night Raw. Those quickly took a backseat to the lawsuit, which is where fans learned most of what there is to understand about this incomprehensible accident.

The public version of the civil case file contains a lot of information that isn’t commonly known; due to her access to documents that were not available to the public, Martha’s book, Broken Harts is the definitive source of information regarding the fact-finding in the case. The book was never a huge seller, and so what it revealed about what really happened in Kansas city are not nearly as well-known as they should be. Additional information in the court record rounds out the picture. It is not any prettier than you’d expect.

The accident and lawsuit centered around the equipment that failed in the stunt, a “quick release” snap shackle manufactured by Lewmar, a British company specializing in marine equipment. If the danger inherent to using that sort of device for a stunt that involved rappelling 78 feet seems obvious to you, it should—the industry standard was a more secure type of locking system used in mountain climbing. According to Broken Harts, WWE had been using eminently qualified theatrical rigger Joe Branam for three years whenever the occasion called for such a stunt; Branam had decades of experience working with the biggest possible names that could require his services, from Disney to musicians like N’Sync. Hart’s book notes that Branam was struck by how, at least three different times, WWE’s then-VP of Event Operations Steve Taylor communicated to him that Vince McMahon personally wanted Branam to use some kind of quick release for the stunts. Each time, Branam repeated that those weren’t safe for human use in this case. How could some small amount of time saved in getting out of the harness be worth such a risk?

Branam’s assistant, Randy Beckman, was used for Owen’s previous “fly-in” six months earlier in St. Louis, which used the more secure “locking carabiner” system. While it went fine, Beckman was “shocked” that Owen did not know that he’d be doing the stunt at all; Beckman had to tell the wrestler himself. Even with a slew of redundancy and safety equipment, Beckman recalled Owen’s anxiety at having to do the stunt. “Don’t drop me,” he told Beckman, “I’m scared.” The rigger made sure to tell Steve Taylor about that.

WWE sought out Branam’s company for a similar stunt on Raw in Orlando just 13 days before Over The Edge; he quoted the same price that he had in previous instances, which was $5,000. Taylor replied that “it wasn’t in the budget.” The rigger soon grew concerned about the stunt. Orlando, he reasoned, was filled with less-skilled labor from the area’s theme parks, and he worried that they would be willing to do the job more cheaply and less safely, perhaps even using the quick release snap shackles that McMahon kept asking about. So Branam asked Beckman to call Taylor, offering to drop the price by 40 percent, to $3,000. Taylor told them that the stunt was cancelled.

“Cancelled” in this case may have just meant “postponed,” but Branam’s fears proved well-founded. The rigger at Over The Edge, Bobby Talbert, was an Orlando resident who generally did rigging for theme park shows.

“I had never heard of the rigger Bobby Talbert prior to reviewing this case,” wrote Brian Smyj, a stunt coordinator specializing in rappelling, in a sworn affidavit for the plaintiffs. “In reviewing this case, I have learned that he had been employed at the time with the Universal Stunt Show in Orlando, Florida. In the stunt industry, people employed at the Universal Stunt Show are known to be the ‘bottom of the barrel’ people in the industry. They take about $30.00 per show.” Garry Roy and Manny Chavez, two other experts, provided similar affidavits.

While some then-WWE personnel have claimed that Talbert had also handled Sting’s descents, that was not the case. According to a deposition from WCW stunt coordinator Ellis Edwards, which was taken as part of WWE’s cross-complaint against Lewmar, Talbert was brought in by WCW’s usual rigger Barry Brazel on just three occasions in 1998, at which point Sting had been doing the stunt for some time. Even then, Talbert was used mainly for occasions in which Sting had to be raised back to the rafters. Per Broken Harts, Talbert told police that Steve Taylor had told him that WWE was looking for a new rigger because its previous hires, Branam and Beckman, had set up Owen in a way that was “too slow for the camera.”

How did the quick release that cost Hart his life deploy? The best guess, per Broken Harts, had to do with how Talbert dealt with a cord that Owen was supposed to pull on just above the ring. Talbert drew that cord across his subject’s shoulder and taped it to the front of his vest with gaffer tape, “allowing a small amount of slack.” That slack was such that other movements of the vest, from deep breaths to Owen adjusting his cape, could accidentally trigger the shackle, which required just six pounds of pressure. (In testing for the lawsuit, a man wearing an outfit similar to Owen’s Blue Blazer gear caused the trigger to release just by adjusting his cape.) Lab analysis also found some kind of grease on the shackle, although when it was applied is not noted in the public file.

While the lawsuit was primarily concerned with what WWE and Vince McMahon did or didn’t do, it also noted that Lewmar, the snap shackle manufacturer, had not issued worldwide warnings after having observed previous similar issues in stunt work and related fields. The product was designed for marine use, mainly on small sailboats; there was no real reason to think it was suitable for human use, although that didn’t keep riggers and other stunt coordinators from using it. Amspec, from which Talbert had bought the equipment and which had aided him in designing the stunt, played their own role in the failure as well. The evidence to that end was so compelling, in fact, that WWE attempted to block Martha Hart settling with the equipment companies for zero dollars, citing a concern for bad faith. WWE, in all fairness, did a compelling job laying out Lewmar’s negligence. They noted that Lewmar was fully aware of the stunt industry inappropriately using their equipment despite repeated accidents, and knowingly continued to provide it to distributors of stunt equipment despite that. WWE settled with Martha and her in-laws for a reported $18 million, though she wrote in Broken Harts that she accepted after WWE “bumped their offer significantly” over their previous figure of $17 million.

WWE then sued Lewmar to recoup the portion of the settlement not covered by insurance. This proved to be an uphill battle.

According to a 2003 Kansas City Business Journal article, Missouri civil co-defendants are not allowed “to sue one another if they are released from the case through a good faith settlement,” hence the aforementioned bad faith concerns. Martha, for her part, wrote that Lewmar was released because their clip “just did what it was designed to do—release quickly on load.” Judge Douglas Long didn’t buy that, though. He allowed WWE to sue Lewmar, and according to a January 2003 statement from WWE, wrote in his ruling that “substantial evidence exists that Plaintiffs’ counsel was motivated by a desire to prevent facts concerning Lewmar’s liability for this accident from coming to light in an effort to construct a punitive damages claim against WWE.”

The same statement adds that “[w]hen testimony was taken from Lewmar representatives in England, no attempt was made by Plaintiff’s counsel to establish the factual basis for Lewmar’s responsibility,” as well as that “[a]s soon as the deposition was over, Plaintiff and her counsel announced they had released Lewmar from the case for no money, even though Lewmar had offered to pay money.” The case went to trial, and the Business Journal article reported that settlement talks began after WWE’s usual outside counsel, Jerry McDevitt, was allowed to testify about the whole chain of events, including the fraud allegations. Lewmar agreed to pay $9 million, which was covered by their insurers.

Even by the standards of a case like this, there was no neat conclusion. Whether it was a legal strategy or a personal call to focus on WWE’s responsibility, Martha Hart and her lawyers did try to keep much of the truth about what happened from coming out. WWE came off terribly, too, both due to the facts of the case and because of typically WWE acts of aggression like suing Martha for violating Owen’s contract by suing outside of Connecticut. It was an ugly resolution to an ugly case. Given that it sprung from the senseless death of one of the most beloved people in the wrestling business, it could hardly have been any other way.

The only narrow silver lining to this tragedy is that more people weren’t hurt. If Korderas had been standing a few inches closer to the corner when Owen fell, or if the three-and-a-half-foot tall masked Mexican wrestler Max Mini was strapped to Owen as originally planned, the outcome could have been more heartbreaking. Martha wrote that “they opted to scrap plans to include Max Mini that night” after “Owen deliberately showed up late” to a rehearsal. One of wrestling’s defining tragedies and darkest moments could somehow have been even worse.

David Bixenspan is a freelance writer from Brooklyn, N.Y., who co-hosts the Between The Sheets podcast every Monday at BetweenTheSheetsPod.com and everywhere else that podcasts are available. You can follow him on Twitter at @davidbix and view his portfolio at Clippings.me/davidbix.