Books

What I Learned Reading Harry Potter For The First Time As An Adult

I was 10-years-old when Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone was first published in the United States — just a year younger than Harry himself was upon meeting readers for the first time — and too deep into my Anne of Green Gables/Boxcar Children series phase to take much notice of the wizarding world that had most of my friends captivated. When Harry Potter achieved bestseller status — landing at the top of the New York Times bestseller list in August of 1999, and sticking around for over a year — the book-lover in me finally took notice (or, rather, my book loving mother and 6th grade teacher took notice, and that was enough for me to at least glance at the novel that was making J.K. Rowling a household and playground name.) Still, for whatever reason, I wasn’t hooked.

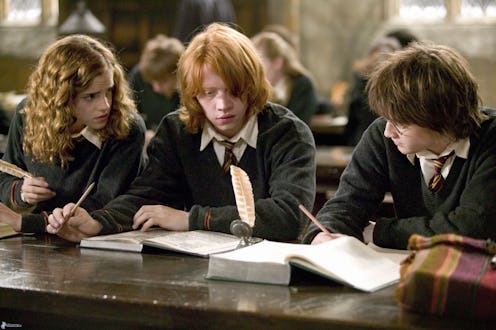

I read Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone a bit later than the rest of my peers, joined them for Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets and Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, (7th and 8th grade, respectively) and then largely fell off the Harry Potter bandwagon. I was entering high school, and for all it’s magic, mayhem, and Dumbledore-bestowed life lessons, I was finding more of what I needed between the covers of Madeleine L'Engle and Sarah Dessen novels than J.K. Rowling’s. Maybe I just didn’t get it. Years went by, and I gave hardly a thought to the wizarding world of Harry, Ron, and Hermione.

But then, in my late (late, late, late) twenties, I began noticing something: Harry Potter hadn’t actually disappeared along with my braces and Teen Spirit deodorant. The Deathly Hallows symbol kept popping up on bumper stickers (I initially thought it signified a state camping permit). Silhouettes of Harry’s lightning-struck spectacles appeared on tees, totes, and as tattoos. The wisdom of Albus Dumbledore was cited alongside that of Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Mother Teresa. I was asked, on more than one occasion, “what house I was in”, without any sort of context, as though this were standard small talk. I realized my peers were still OBSESSED with Harry Potter. This wasn’t just a cult following — this was a lifestyle, and practically everyone was in on it.

Still, Harry Potter and his magical comrades didn’t immediately make their way onto my bookshelves. I became something of a Potter-skeptic, asking self-proclaimed “Potterheads” to justify their obsessions and offering alternative reading material to anyone who would listen.

"This wasn’t just a cult following — this was a lifestyle, and practically everyone was in on it."

Then, Donald Trump began winning Republican primaries.

Now, I’m not saying that my eventual decision to read all seven books of the Harry Potter series in the spring of 2016 was a direct response to the violence and vitriol building in American politics. At least, not in any conscious way. But while reading Harry Potter, nearly two decades after the first novel appeared in my Scholastic Books pamphlet, wasn’t directly related to Donald Trump’s Republican presidential nomination and the subsequent implosion of civilized society, my surprising (at least to me) and immediate love for them was.

That the Harry Potter series tells a story about political resistance, one wherein small and diligent acts of goodness, with time, (in this case, a rather long time) succeed over sudden and tremendous moments of great evil is something I couldn’t have appreciated if I’d left Harry Potter back in middle school where I briefly discovered him. Dumbledore’s unfailing optimism in the face of tyranny wouldn’t have struck quite as resounding a chord. “Don’t you see? Voldemort himself created his worst enemy, just as tyrants everywhere do!” Dumbledore says in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. “Have you any idea how much tyrants fear the people they oppress? All of them realize that, one day, amongst their many victims, there is sure to be one who rises against them and strikes back!” (Go Stormy, go Stormy.)

"That the Harry Potter series tells a story about political resistance, one wherein small and diligent acts of goodness, with time, (in this case, a rather long time) succeed over sudden and tremendous moments of great evil is something I couldn’t have appreciated if I’d left Harry Potter back in middle school where I briefly discovered him."

His words about courage, even when faced with mounting peer pressure, wouldn’t have felt quite so pointed — the fissures between myself, family members, and friends who supported Trump, still linger. But Dumbledore, in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, reminds readers that: “There are all kinds of courage… It takes a great deal of bravery to stand up to our enemies, but just as much to stand up to our friends.”

The way the novels address power dynamics — from the unassuming and resilient power of Dumbledore, to the bookish power of Hermione Granger, to the small but dehumanizing power of Dolores Umbridge, to the overwhelming but self-destructive power of Voldemort — couldn’t be more timely. One could easily look at the faces that linger in the Trump White House, substituting Voldemort for the president, his Death Eaters for the politicians who languish in devoted powerlessness behind him. “It is a curious thing,” Rowling writes, in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, “but perhaps those who are best suited to power are those who have never sought it.”

Plagued with a cultural moment that is being called “post fact”, Dumbledore’s unwavering belief in the power of objective truth seems, if a tad starry-eyed, still encouraging. “Time is short, and unless the few of us who know the truth stand united, there is no hope for any of us,” the professor reminds his students, in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. “We are only as strong as we are united, as weak as we are divided.”

"Plagued with a cultural moment that is being called “post fact”, Dumbledore’s unwavering belief in the power of objective truth seems, if a tad starry-eyed, still encouraging."

These are values: responsible citizenship, courage, equality, truth, resilience, that, in my experience (both as a former child and someone who spends a lot of time with children now, as an adult) young people often take for granted. I certainly did. My childhood, while privileged, was not without its relative hardships — and yet, the ideas that good would ultimately win out over evil, that the world was a place ordered by self-evident truths, that people were rewarded for their courage even when it was unpopular, and that those most deserving of great power would ultimately be the ones to achieve it seemed unambiguous. Surely, some of us become disillusioned sooner than others. But while, as a young person, I would have been entertained by these fictional narratives, they wouldn’t have seemed quite as radical to me as they did to my disillusioned, somewhat wearied, 30-year-old self.

Which is why, perhaps, Harry Potter is actually a story for adults. Maybe the Potter-fervor I’m observing in my 30-plus-year-old peers is because we just need the magic of the wizarding world more. Maybe Dumbledore’s reminder that: “It was important to fight, and fight again, and keep fighting, for only then could evil be kept at bay, though never quite eradicated…”, was actually meant for us.