Najib says Malaysia-Singapore jousting is over. Is it really?

Relations between the once bickering neighbours have warmed under leaders with personal chemistry. But it’s not all smiles and handshakes

For decades after the end of their acrimonious post-independence union in 1965, the former British colonies publicly bickered over everything; the ownership of a railway station, water supplies, rocky outcrops in the sea, airspace and even the provenance of a shared cuisine they both call their own.

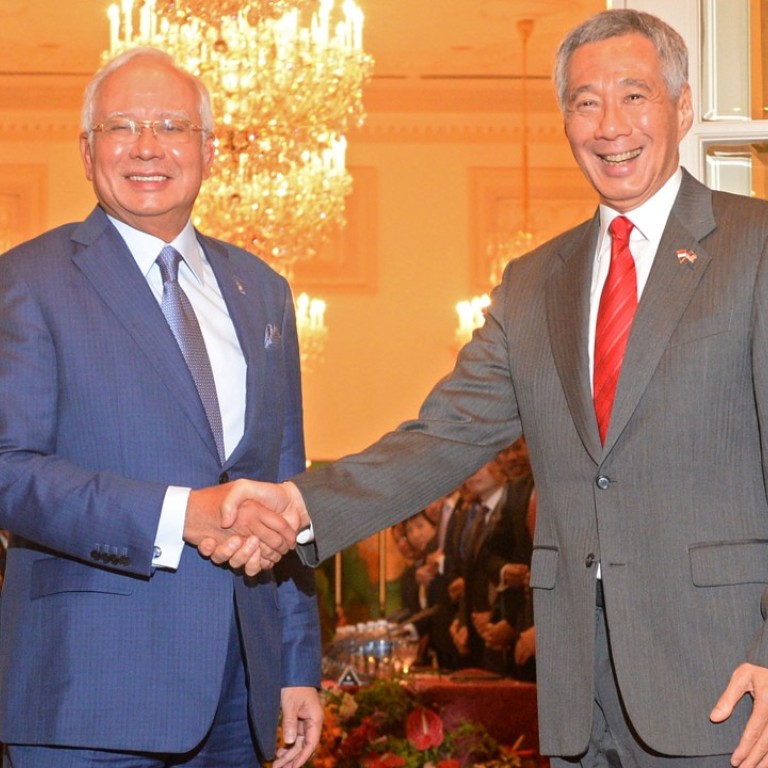

Najib’s dovish comments about the Lion City this week, during an annual summit in the city state with Singaporean counterpart Lee Hsien Loong, underscored the near decade-long detente in place between the two countries.

The period of relatively warm relations coincides with Najib’s ascension to the premiership in 2009.

During a press conference on Tuesday with Lee, Najib said he did not want ties to return to the “era of confrontational diplomacy and barbed rhetoric”, adding that the fraught relationship of yesteryear was “an era we want to forget”.

Whiff of discontent in Singapore as Malaysia courts Chinese market for its durian

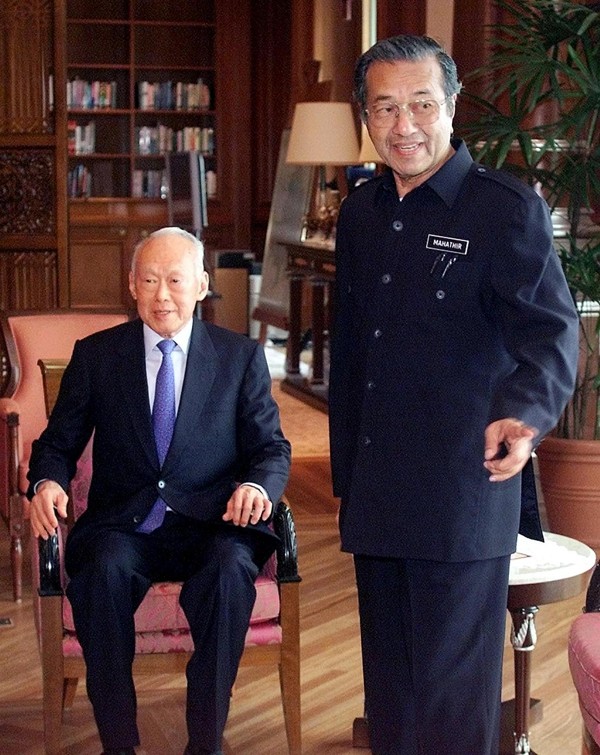

It was a thinly-veiled critique of his former mentor turned nemesis, Mahathir, and his hardline stance towards Singapore during his years in office. At age 92, Mahathir has crossed aisles to take on the premier in upcoming elections, posing the biggest threat to Najib.

Mahathir says he is taking on Najib because he wants to rid Malaysia of a “kleptocracy”, or thieving government, but the former leader has in the past also assailed the current premier for not following through with plans to build a new bridge to replace the existing causeway with Singapore. Singapore was not keen on that project because of its prohibitive cost.

Such intransigence over joint infrastructure projects have become a thing of the past. Political watchers and former diplomatic insiders say the scale of economic cooperation between the two countries in the past decade show that the accelerating detente has manifested itself in real terms, and not just in pronouncements by the respective leaders.

The two prime ministers this week also officially opened two real estate developments in downtown Singapore that were jointly developed by their respective sovereign wealth funds.

The projects, worth some S$11 billion (HK$65 billion), were part of a land swap deal struck by Najib and Lee in 2010 that saw Malaysia return 217 hectares (536 acres) of railway land in Singapore that were vested in its control from the colonial era.

Such a scale of cross-investment was not seen during the era of Mahathir and Lee Kuan Yew.

Both leaders, known for their headstrong personalities, spent decades caught up in various arguments from the pricing of Malaysia’s water supplies for the resource-poor city state to the Singapore military’s use of Malaysian airspace.

On Lee’s death at age 91 in 2015, Mahathir said in his condolence note that “there was no enmity, only differences in our view for what was good for the newborn nation”.

Najib and Lee replaced confrontation with “cooperation at different levels of government and on a variety of issues including trade and investment, defence and security as well as cultural diplomacy”, said Mustafa Izzuddin, a Singapore-based researcher on southeast Asian diplomacy.

Mustafa and other Malaysia-Singapore watchers say the main reason for the thaw in bilateral ties is the personal camaraderie between Lee and Najib.

Can China really deliver Malaysia’s Singapore slayer?

The two are contemporaries – Lee is 65 and Najib is 64 – and their fathers were both revered independence leaders. Lee is the eldest son of Lee Kuan Yew, while Najib is the eldest son of Malaysia’s second premier Abdul Razak.

Syed Hamid Albar, who served as Malaysia’s foreign minister from 1999 to 2008, told This Week in Asia there was nothing wrong with Najib’s latest comments about his former mentor’s approach with Singapore.

“Najib’s foreign policy assessment [of the Mahathir era] is to the point. It is also no secret and public knowledge that both sides suffered ups and downs of tense political bilateral relations,” the former Mahathir lieutenant said.

He added: “Both Hsien Loong and Najib do not have historical baggages to carry. Both leaders have a greater sense of confidence in each other.”

Why Malaysia is fighting Singapore over a rock

Some observers caution against being too bullish about the strengthening bilateral ties, however.

“There continues to be traces of suspicion towards Singapore within Malaysia’s foreign policy and defence establishments, though considerably less so in recent years,” said Shahriman Lockman, a senior analyst with the Institute of Strategic and International Studies in Kuala Lumpur.

He said: “There is this sense that Malaysia needs to be extra careful and play its cards close to the chest when it deals with Singapore – that Singapore would swiftly capitalise on any mistake or hint of compromise.”

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2008 ruled that the islet – called Pulau Batu Puteh by the Malaysians – belongs to Singapore.

Malaysia last year filed for a review of the ruling, citing the discovery of new evidence that its officials say support their case.

Singaporean officials say the fresh Malaysian challenge has no merit. Singapore’s Lee said in November he was “not sure what Malaysia’s motive is, but their general election is coming, which may have something to do with it”.

The dispute was not publicly discussed by Najib and Lee in their summit last week.

Mustafa said the omission was probably down to expectations by Singapore that the matter would be settled in its favour by the ICJ, and in Malaysia’s case, it was an issue for “domestic consumption … and therefore not germane or advantageous for enhancing Malaysia-Singapore relations”. But “just as Pedra Branca or Batu Puteh was brought up in past elections in Malaysia, it is likely to be brought up again in the next election”, he said. ■