CHIPPEWA FALLS, Wis. (AP) - When brain analysis revealed that former National Hockey League player Jeff Parker had chronic traumatic encephalopathy, it came as no surprise to his family.

For Jeff’s brother, longtime Chippewa Falls High School boys hockey coach Scott Parker, the recent diagnosis by researchers at Boston University’s CTE Center was confirmation of what he already knew in his heart.

The Leader-Telegram reports that Scott had seen his younger brother struggle for years with the after-effects of too many blows to the head - including concussions sustained 15 days apart in his last two games as a pro that ended his NHL career - before Jeff died last September at age 53 from a blood infection.

“I knew it all along - when he was late for his brother John’s wedding, when he went to the wrong place for a TV interview, when he would come to my house and go down in the basement because he needed to be in a dark place,” Scott said.

Still, the formal diagnosis, which came after family members decided to donate Jeff’s brain to the CTE Center in hopes of advancing concussion science and, ultimately, care for former hockey players, was emotional for the Parker family. Researchers determined Jeff had stage 3 CTE, the second-most-severe of four possible stages.

“We’re sad,” said Scott, a teacher in the Owen-Withee school district. “This suggests maybe Jeff was suffering even more than we knew.”

John, of Madison, characterized his reaction to the news as making him feel “kind of numb and sad at the same time,” but he remains hopeful the family’s decision to release Jeff’s test results will lead to more support for other current and former hockey players struggling with CTE, the degenerative brain disease medical experts believe is caused by repetitive brain trauma.

However, NHL executives, following the playbook previously used by National Football League officials, so far have denied any link between CTE and hockey.

“We know Jeff would have wanted to help the next guy,” John said. “He was all about helping others.”

Jeff was the standout in a rare hockey family in which all three brothers, who grew up in White Bear Lake, Minnesota, won national championships with their college teams - Scott with UW-Eau Claire in 1984, Jeff with Michigan State in 1986 and John with Wisconsin in 1990.

The talent was evident even as a young boy when Jeff was firing pucks over the net when his teammates were just learning to lift the puck off the ice. Jeff went on to earn high school all-state honors as both a defenseman and forward in Minnesota before playing junior hockey, skating for Michigan State and eventually suiting up for 137 games over five seasons, from 1986 to 1991, in the NHL for the Buffalo Sabres and Hartford Whalers.

Though he was a good skater, Scott said, Jeff was pressured to become a fighter, often squaring off for bare-knuckle fistfights with other players. In retrospect, Scott said, that likely led to additional blows to the head, despite Jeff’s relatively brief NHL career, beyond what players typically endure through checking and colliding with the boards.

Jeff’s career ended abruptly when he suffered a concussion and was knocked unconscious for five minutes after a violent collision with the stanchion holding the glass to the boards during a 1991 game against the Washington Capitals. He later told people it felt like his head “went oblong,” and he didn’t remember what team he played for when he regained consciousness.

Scott said seeing the blow on TV in a Water Street bar made him sick to his stomach.

Jeff endured another concussion in his first game back and never played another NHL game.

“It really doesn’t matter if you play one game or 1,000 games,” Scott said. “If you get hit like that - you get your cheek caved in or your nose knocked to the side of your face - you’re going to have some issues.”

For Jeff, those issues included memory loss, extreme headaches, ringing in his ears, sensitivity to light, decreased hearing, lost sense of smell and taste, vertigo and lapses in judgment that led to him squandering the big paychecks he made as a professional athlete, in part on what Scott described as self-medicating for his health problems.

His family lost track of Jeff during a stretch in the 1990s when he apparently was homeless. The brothers are thankful they never heard of Jeff, a father of three, exhibiting the kind of violent behavior associated with some CTE patients.

Scott said he first noticed Jeff was having difficulties when the former NHL player served as a volunteer assistant coach for Chippewa Falls High School during the 1993-94 season. Even then, Jeff was struggling with money management and figuring out his direction in life.

Not that anyone would have known it from talking with Jeff, a tough guy whose standard response when his brothers asked if he needed any help was, “I’m fine,” John recalled, adding, “He didn’t want help because he didn’t think he needed it, but he did. He just tried to do the best he could every day.”

Jeff did, however, sign on as one of more than 100 former NHL players named as plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit against the league. The suit, still active in U.S. District Court in Minneapolis, maintains the NHL concealed information from players about the risks and long-term effects of concussions.

Despite his troubles, Jeff enjoyed sharing his knowledge of the game with the Chi-Hi players, and they appreciated the attention and advice from someone who had reached the pinnacle of their sport.

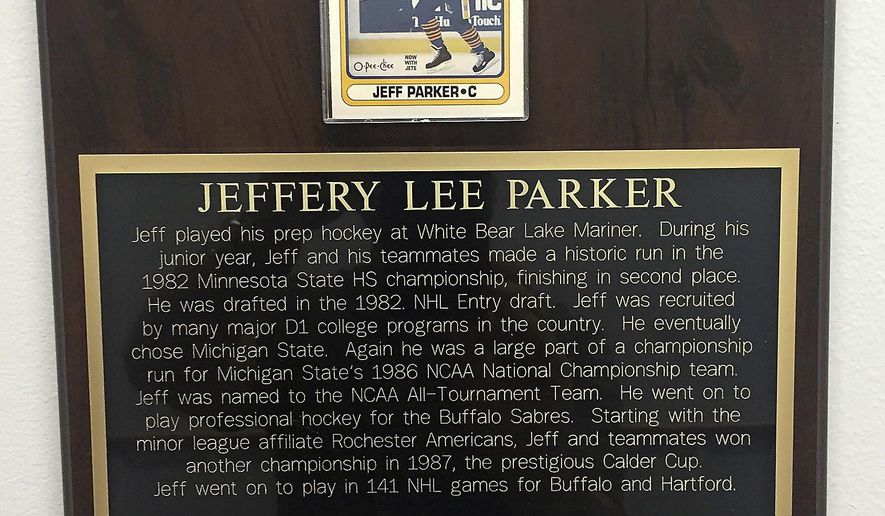

Even after his stint as a volunteer coach ended, Jeff routinely attended some Chi-Hi games, talked with the team and donated money for equipment. He is commemorated with a plaque in the hallway outside the home team’s locker room at Chippewa Area Ice Arena, and his Sabres jersey, helmet, photo and stick comprise a makeshift memorial in the first locker.

Frank Nordstrom of Chippewa Falls saw Jeff’s influence when his son, Jerod, played hockey for the Cardinals from 2009 through 2012.

“If you wanted some pointers, Jeff was always there for the kids,” said Nordstrom, who became friends with Scott and Jeff.

When Jerod advanced to play junior hockey, Jeff continued to attend games and offer advice.

“For a guy who was a physical enforcer in hockey, you would never know it off the ice,” Nordstrom said. “He was just a big teddy bear with a huge heart.”

That reputation has come through in dozens of supportive texts and social media posts Scott has received since The New York Times broke the news of Jeff’s diagnosis on Friday. The notes, which brought tears to Scott’s eyes, ranged from former high school, college and pro teammates raving about Jeff’s kindness, to a junior high classmate recalling how Jeff scared off a bully and took the boy under his wing, even sitting next to him in study hall.

“Because of Jeff I have raised my kids to be that kid that stands up for the bullied, be the kid that welcomes the new kid, be that kid that doesn’t join in with the bullies because it’s easier,” the former classmate wrote.

Though Jeff rarely complained, Nordstrom said, he could tell his friend’s health was deteriorating over the past decade or so of his life. It was most evident during conversation.

“He’d either repeat himself a lot or he would be talking and then just kind of trail off,” Nordstrom said. “That was a telltale sign that something wasn’t right.”

Advancing disease

Testing by CTE Center researchers revealed dark areas on Jeff’s brain that are evidence of the buildup of a protein called tau, which forms clumps that slowly spread throughout the brain, killing brain cells.

“Jeff Parker’s brain was at such a stage that the disease was taking over his brain,” center director Dr. Ann McKee said in a statement from the Concussion Legacy Foundation, a partner in the CTE Center. “It didn’t matter what he did from here on in, the disease was just going to get worse and worse.”

Parker is the seventh former NHL player diagnosed with CTE, and the sixth at the CTE Center, along with Derek Boogaard, Bob Probert, Reggie Fleming, Rick Martin and Larry Zeidel. No former NHL player has been studied after death and tested negative for CTE, the foundation indicated.

“The take-away message from Jeff Parker’s diagnosis is that repetitive brain trauma can destroy a life, and we need to work harder to prevent concussions and, frankly, all hits to the head,” said Chris Nowinski, co-founder and CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation. “It’s not just NHL players who are dying too young with brain damage; we are seeing it in all contact sports and in amateur athletes.”

Nowinski said concussion protocols shouldn’t even be part of the conversation.

“They matter, but we can’t be sure that better concussion management would have prevented Jeff’s CTE,” Nowinski said. “We should manage concussions well to prevent bad concussion outcomes, but to prevent CTE we need to try to prevent all hits to the head, not just concussions.”

The debate over what to do about CTE is difficult for the Parkers. They are the ultimate hockey family, but they also recognize the game took a tragic toll on Jeff’s brain.

“We love hockey,” John said. “Hockey’s done wonderful things for our family, but we’ve got to find ways to make the game safer without changing the game. The game is awesome.”

As the Chi-Hi coach for the past 31 seasons, Scott, 55, is forced to walk an uncomfortable tightrope.

“I love the game of hockey, but it’s my brother,” Scott said, his head down and his voice trailing off. “I’m going to continue to love my brother and fight for him, and he wanted to see other guys get help.”

Thankfully, Scott said, the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association doesn’t allow fighting in high school hockey. In addition, local schools take the risk of concussions seriously, in part by requiring all athletes participating in contact sports to take cognitive tests to establish a baseline before they compete and then pass a follow-up test after suffering a head injury before they can return to action.

“Player safety is the No. 1 thing in high school sports,” he said. “Almost none of these kids are going to go on to play professional sports, but we want to make sure they are able to go to college, enter the workforce and raise families.”

Scott, whose three broken bones in his neck during high school hockey didn’t deter him from playing in college, said he begins talking about ways to avoid head injuries - keeping sticks down, checking safely, not leading with the head when contacting other players - on the first day of practice every year.

Despite those efforts, he said, hockey is so fast that injuries happen.

“If an athletic trainer says a kid is injured, there’s no arguing. He’s out and not allowed to participate again until he’s cleared,” said Scott, who’d like to see the NHL take more precautions, too, especially related to concussions.

He noted that NHL players make the league a lot of money.

“I don’t want to come across as an NHL hater, because I’m not,” Scott said. “I’m a high school hockey coach, so I’m not going to change the game of hockey, but I would like to see the NHL take care of the guys.”

Scott said he wants to see more education about head injuries and possibly health care for life for guys who make it to the NHL. John called for advances in head protection and counseling for players.

“It’s one thing to have a twisted arm or leg, but it’s a whole other thing when your brain is scrambled,” Scott said. “Guys need to realize that this brain stuff doesn’t go away.”

___

Information from: Leader-Telegram, http://www.leadertelegram.com/

Please read our comment policy before commenting.