City's European failings slow Pep's rise to true greatness

Wait for further Champions League glory has the potential to tarnish Guardiola's legacy

A treacherous aspect of genius is that sometimes it goes missing when you need it most. Even worse, you might just happen to mislay it permanently.

Maybe this is an extreme reaction to Pep Guardiola's growing crisis in the Champions League, which once seemed to be his natural terrain.

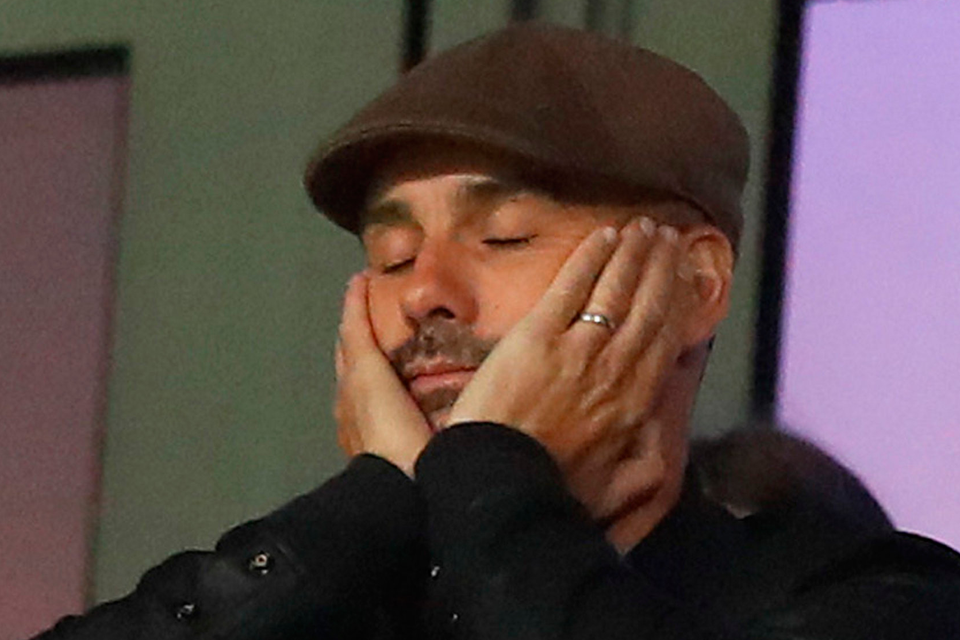

Perhaps so, but it was certainly not hard to see flashes of despair on his face when he sat in the gods at the Etihad Stadium this week as his Manchester City looked utterly miscast as favourites to win the greatest prize in club football.

Guardiola was so far from the action, of course, because of his emotional freak-out when Liverpool so brilliantly knocked them out last season. But that was Liverpool, finding a breath-taking stride on behalf of Project Klopp.

How does Guardiola keep his equilibrium, while finding his old inspiring touch, after City slipped to their fourth straight defeat in the Champions League against Ligue 1 also-rans Lyon, a loss which at times seemed hard to distinguish from outright surrender?

At the touchline, Guardiola's deputy Mikel Arteta looked less a commander sent to the front to hold a position with crack, battle-seasoned troops than the stunned minder of disgruntled column dodgers.

That is an unlikely description of Bundesliga veteran Ilkay Gundogan but a man who normally relishes the heart of a game came off the field early and inevitably so as one of the more conspicuously defeated.

Gabriel Jesus looked less the blessedly adroit enfant terrible of the world's young strikers as a mildly interested spectator. The defence was porous at critical moments.

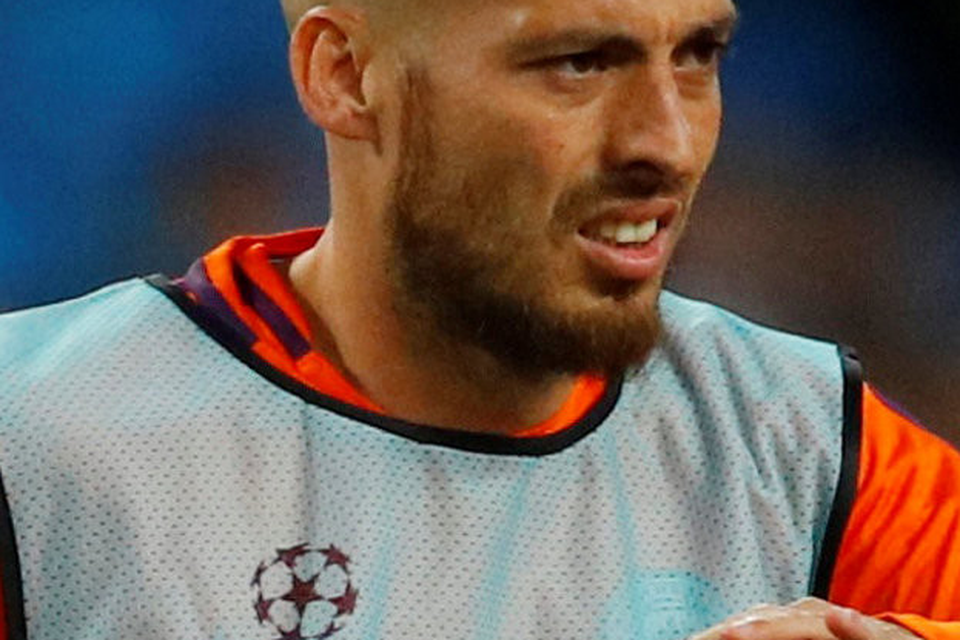

David Silva was as near to anonymous as he will ever be on a football field. Sergio Aguero, so often the spirit of City, came late and produced just one, galvanic, unfulfilled moment. Leroy Sane's brilliance evaporated.

And these were the record-breaking titans of the Premier League, the rich, powerful league in which they will almost certainly re-exert themselves on tomorrow's visit to under-gunned Cardiff City.

But then nobody needs to tell Guardiola where one of the world's leading coaches - and in his case arguably the most revered - best augments his reputation. It is not in the trench warfare of domestic football, however luminous some of the performances, but in the heights of Europe, places like the Bernabeu, Nou Camp and San Siro.

It was at the Nou Camp where Guardiola made his name and his legend.

It is at the Etihad Stadium where he has continued the habit of spending the earth and inhabited somewhere far less glorious than where he won two Champions League titles, three La Liga crowns, and so superbly helped to remodel the role of the world's greatest single talent, Lionel Messi.

Can he still shape careers in such a profound way, can he still triumph in Europe with a team with which he mostly eviscerated English football last season?

If it was a matter of sheer football intelligence, and flair, not to mention unlimited resources, it is hardly a serious question - and we can certainly discount the crude voodoo currently being applied to him by the agent of former City giant Yaya Toure.

No, the challenge is in finding that old messianic touch which made more of a player of Messi than anyone, except maybe Guardiola, could have imagined, which turned such as Andres Iniesta and Xavi into consistently phenomenal midfield influences and so often made his Barcelona unplayable.

What you must begin to wonder is if, even at the relatively youthful age of 47, Guardiola has done the best of his work, already hit the extremes of his talent - and that last season's Premier League tour de force created expectations which flew beyond the wider realities of the top European games.

The fact that can easily be forgotten is that it is now eight seasons since Guardiola occupied the peak of Champions League success.

And that it was maybe then when he made a possibly momentum-breaking decision to take a year's sabbatical amid the myriad diversions of New York City.

Some of his more recent haunted expressions might just be explained by the memory of a warning delivered at the time by Alex Ferguson, whose Manchester United had been swept aside at Wembley as Guardiola claimed his second and last European crown as a coach.

Ferguson said that leaving a group of players which had so beautifully decorated the Wembley field was a monumental decision for any football man, a potential life-changer because such good fortune to have such men at your disposal might never come again.

The United chief spoke with much feeling for it was the second time in three seasons that Guardiola's men had outplayed his team in the most important match of any club season.

On the first occasion, at Rome's Stadio Olimpico, the wisdom behind Messi's new role as a false centre forward was rewarded with a headed goal.

Now the challenge facing Guardiola goes beyond such niceties of insight and instinct - and any fresh burst of spending, the urgent need for which he must hope has been sharply lessened by optimistic news on the returning fitness of his most important strategic talent, Kevin De Bruyne.

The task, quite simply, is to make a group of players believe in their right not only to compete at the highest level but also dominate it. This week that ambition seemed to rest on some distant planet.

But then we should indeed remember it is eight seasons since the great coach persuaded a group of talented players that they were the rightful champions of Europe - and that the season before that Jose Mourinho's Inter Milan delivered him a semi-final knock-out of perfectly waged and most cynical defence.

When the ageing Jupp Heynckes left Bayern in 2013 he bequeathed the succeeding Guardiola the Champions League title, but over three years of Bundesliga success it was a burden rather than a gift.

This week the weight on Guardiola has rarely seemed so heavy. He must be the master of Europe again because if he isn't soon enough he is in danger of becoming just another coach, albeit one with domestic dominance.

On the biggest stage in club football, however, the wait to underline his greatness is growing ever longer.