The Clinton Impeachment, as Told by the People Who Lived It

Twenty years ago, Bill Clinton became the first president to be impeached since Andrew Johnson, in 1868. We offer a recounting by people who played a role.

In 1998, the Republican-led House of Representatives voted to impeach President Bill Clinton on one charge of perjury and one charge of obstruction of justice. The articles of impeachment had their origin in a relationship between the president and a 22-year-old White House intern, Monica Lewinsky. The intimate details, revealed by an independent counsel, had consumed the country for 11 months: part morality tale, part soap opera, part high-stakes knife fight. Politically, the country was divided—less so than now, but ferociously. We have been living with the consequences of the Clinton impeachment ever since. The political battle has stoked resentments, influenced elections, given rise to conspiracy theories, and prompted many to think about the nature of the relationship that lay at its core—one that Lewinsky has called consensual but has come to see as a “gross abuse of power.” With the anniversary approaching, The Atlantic set out to tell the story of that battle—fought by lawyers, politicians, and an assortment of hired guns—through the differing recollections of people who played a role in investigating, prosecuting, or defending Bill Clinton.

I. a breaking story

In July 1995, Monica Lewinsky started work at the White House, initially as an intern. She and the president developed a flirtatious rapport, which intensified during a weeklong government shutdown, during which interns served as support staff. By early 1996, White House aides had grown concerned about the relationship. In April, Lewinsky was reassigned to the Pentagon, where she became friends with Linda Tripp, a career civil servant who disliked the Clintons. Lewinsky told Tripp that she had had a sexual relationship with the president, which Tripp in turn told the Newsweek reporter Michael Isikoff, withholding Lewinsky’s name. On October 6, 1997, Tripp invited Isikoff to a meeting with the conservative literary agent Lucianne Goldberg. Tripp revealed that she had surreptitiously recorded her phone conversations with Lewinsky, and offered to play one of the tapes for Isikoff.

Michael Isikoff: I’d been talking to Tripp for some months, so I assumed the meeting was to provide me some further details about who the woman was. I was not quite sure what to expect or what I would learn, but when Linda Tripp provided the name and a few details, I felt I had made some progress.

Then they informed me they had been doing the taping. It was a little bit of, like, “Whoa, what’s going on here?” That threw me for a loop. It became clear that there was nothing conclusive, but also that this was an ongoing process—she was still taping, and she and Lucianne were trying to enlist me in their scheme. Listening to that tape would not have brought me any closer to publishing a story. I had gotten what I wanted to get, which was the name.

Lucianne Goldberg: He didn’t want to listen. He had a car downstairs waiting to take him to some TV show. The tapes just stayed in the shopping bag for several weeks.

Tripp also tipped off the lawyers representing Paula Jones in a lawsuit, filed in 1994, accusing Bill Clinton of sexual harassment for an incident that allegedly took place in Arkansas in 1991. On December 5, 1997, the president’s lawyers received a witness list that included the name Monica Lewinsky. Ten days later, Jones’s lawyers requested that the White House “produce documents that related to communications between the President and Monica Lewisky [sic].” Around 2 a.m. on December 17, Clinton called Lewinsky and told her, as she later recalled, that it “broke his heart” to see her name on the list. Meanwhile, others were scrambling, including the Washington lawyer Robert Bennett, who was representing Clinton in the Jones case.

Robert Bennett: Her name was misspelled, and I didn’t really know who she was. Bruce Lindsey [the deputy White House counsel] told me she was an intern who had brought pizza to them on the day the government had shut down. He sort of brushed it off. You know prosecutors—you always start at the bottom, and maybe it’s somebody who’s heard a rumor. Sometimes people go on fishing expeditions.

On January 17, 1998, Clinton was deposed in Washington by Paula Jones’s lawyers and denied having “a sexual affair” with Lewinsky. Bennett cited an affidavit executed by Lewinsky stating that “there is absolutely no sex of any kind in any manner, shape or form, with President Clinton,” and the president testified that the affidavit was “absolutely true.” At the outset, the Jones team introduced a 92-word “Definition of Sexual Relations.”

Robert Bennett: The deposition was bizarre, to say the least. Clinton was there, and we asked that the judge be there. If you’re at a deposition and someone asks your client something you don’t think is appropriate, the usual situation is that he has to answer and then we later say to the judge, “Strike it,” because we objected. That doesn’t work very well with a president. If the judge was in the room, she could rule immediately on the propriety of a question.

I can’t remember the exact wording, but the plaintiff’s lawyers had this very involved definition of sexual relations, which the president took full advantage of in answering.

Meanwhile, Isikoff was close to breaking the story of the president’s affair, but after meetings on January 17, Newsweek editors decided to hold the story from that week’s edition. That night, the Drudge Report scooped Isikoff, running its revelations under the headline “Newsweek Kills Story on White House Intern.”

Lucianne Goldberg: I gave it to Drudge. By the time Newsweek turned it down, Isikoff was fit to be tied. They made him wait until late, late on a Saturday night. He was absolutely pissed.

I found myself with this hot potato. So I talked to some friends of mine that had been along for the ride, Ann Coulter being one of them. She said, “Why don’t you call Drudge?” I think it was Ann, or my lawyer, or Tripp’s lawyer. Drudge broke it within the hour.

Michael Isikoff: The New York Times asked me if I felt suicidal tendencies afterward. What I told them was “No, I don’t think I had any suicidal tendencies. But I won’t deny that I might’ve had some homicidal tendencies.”

Lanny Davis, a law-school classmate of Bill and Hillary Clinton, was due to leave the White House at the end of January after a stint defending the administration in several other scandals. He learned of the Lewinsky story when a reporter called.

Lanny Davis: I was sitting at my kitchen table with a glass of scotch. I got a phone call from Peter Baker of The Washington Post. He said, “You’ve got 90 minutes. What’s your comment on President Clinton having an affair with a young intern named Monica Lewinsky?” I said, “Monica who?”

I hung up the phone, called the White House, and got John Podesta, the deputy chief of staff on duty. He told me to come to the White House. When I got there, I went to the outer administrative office of the Oval Office and asked President Clinton’s special assistant, Betty Currie, if I could talk to the president about a breaking story. She told me he was in an important meeting in the Oval Office and couldn’t be disturbed. By the look on her face, I guessed that she knew what the story was about.

On January 21, Clinton told PBS’s Jim Lehrer, “There is no improper relationship.” Five days later, during a White House news conference on education, he went further: “I did not have sexual relations with that woman—Miss Lewinsky. I never told anybody to lie, not a single time—never.” The next day, Hillary Clinton appeared on the Today show and made the first reference to a “vast right-wing conspiracy.” Meanwhile, the president and his aides—James Carville, Robert Shrum, and Mark Penn among them—were preparing for the upcoming State of the Union address.

James Carville: I was in San Francisco, at a Hyatt hotel, trying to digest the new information. I always kind of thought people figured it out for what it was. Maybe it’s just growing up in Louisiana or maybe it’s just my kind of view of the world, but it was about sex, and lying about sex, in my world—you know, it’s different. He lied about it because he didn’t want his wife and other people to find out. Okay. That bothers me about one-100th of 1 percent. I was way more upset when they passed the welfare bill.

“I show up for a State of the Union speech prep, and the place looks like a bomb shelter. Everybody’s in the corner, they’re whispering, they’re huddling. Clinton had made the strong denial, which was just false.”

Robert Shrum: We went into the Cabinet Room. It was about eight or nine days before the speech. And Bill Clinton was not Bill Clinton. He really wasn’t interacting. I had known him since college, and I said, when we were done, “Can I see you for a minute?” And I said, “Look, I don’t want to know anything about this stuff, but a week from now, when you give this speech, Congress is going to make a judgment about you.” What I didn’t say, but meant, was that people are going to decide whether you can still be president.

The other thing was, we had all sorts of people sending in passages about the scandal that they thought he should begin the speech with. I said, “I think this is the craziest idea I’ve ever heard. If we do this, that will be the news. There will be no oxygen left for anything else.”

Mark Penn: I show up for a State of the Union speech prep, and the place looks like a bomb shelter. Everybody’s in the corner, they’re whispering, they’re huddling. Clinton had made the strong denial, which was just false. So they decide not to hold the regular speech prep. It was just me and Podesta with the president in the Cabinet Room. And he very artfully told me something like “I did not have intercourse with that woman,” which said to me all I needed to know. I’d been around the president for a number of years. He was very precise in his phrasing.

II. THE INVESTIGATION

Since 1994, a team led by Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr, a former federal judge and solicitor general, had been investigating a series of scandals involving the Clintons, beginning with the failed Whitewater real-estate deal and expanding to include other matters—Travelgate, a contested shake-up of the White House Travel Office; Filegate, which involved allegedly improper use of FBI background checks; and the apparent suicide of White House counsel Vince Foster, whom conspiracy theorists believed had been murdered. Members of Starr’s team included Brett Kavanaugh, now a Supreme Court justice, and Rod Rosenstein, now the deputy attorney general. As the Jones lawsuit moved forward, the Office of the Independent Counsel seemed to be winding down its inquiry. At drab quarters in Little Rock and Washington, lawyers and FBI agents sorted through documents on paper, sent faxes, and pecked at WordPerfect. Starr’s office first became aware of the Lewinsky story in January 1998, when a lawyer with knowledge of the Paula Jones case tipped off a staff lawyer about a story that Linda Tripp wanted to tell. The staff lawyer was unaware that the information had come from the Jones team. He insisted that Tripp come forward. On January 12, she did.

On January 13, Tripp met Lewinsky for lunch, wearing a wire provided by FBI agents working for the independent counsel. On January 16, Starr sought and was granted permission to expand his investigation, and later that day FBI agents and prosecutors ushered Lewinsky into a room at the Ritz-Carlton in Arlington, Virginia, and questioned her for 11 hours.

Paul Rosenzweig was the lawyer who got the tip about Tripp. Sidney Blumenthal was an assistant and special adviser to the president, responsible for, among other things, media outreach.

Paul Rosenzweig: At some level, as I look back, everything happened as it should. Some friends of mine told me this story about this woman, Monica Lewinsky, who they said was going to lie in the Jones case and who was getting a job through Vernon Jordan [a Clinton adviser and friend], and that sounded a lot like some of the hush-money investigations we’d been doing. And so I told my boss, and he said, “Have Tripp come in the front door and call me.” I conveyed that message, and then she came in. So in some way I took a tip, I gave it to my boss, and my boss said, “We don’t take tips. I want the testimony of a live witness. Bring it on.” When you say it that way, it doesn’t sound at all odd.

In retrospect, I regret not asking more questions, like: How did this information come to you? What’s your role in this affair? Who else knows about it? I think that’s the place where, if I could go back and change history, I would’ve counseled Starr to let the Department of Justice conduct the investigation. It wasn’t close enough to our original remit.

Sidney Blumenthal: We did not fully know what we know now about what was going on in Starr’s office. We knew that they were politically motivated, we knew that they were leaking grand-jury information in violation of Federal Rule 6(e) to reporters, and that they were obsessed with media relations and controlling the narrative. But we didn’t know that they had divided their office into what they called a “Likud faction” and “commie wimps” and written it on a blackboard with names underneath. We learned that afterward.

Paul Rosenzweig: It had certainly entered many of our minds that Lewinsky was potentially a fabulist. I remember the day that we knew the story was real. Betty Currie had knowledge of what was happening—Lewinsky’s visits to the Oval Office. She got a subpoena for anything relating to Monica Lewinsky. Her lawyer walked in with a box of gifts that Bill Clinton had given to Lewinsky, and that she had boxed up and given to Betty Currie for safekeeping. Now you have the president giving Monica Lewinsky gifts, and they’re real gifts. They’re not like something the president gives everybody. One was a T‑shirt from Martha’s Vineyard. He’d been to the Vineyard for his vacation. So the connection between the president and Monica Lewinsky—we know it’s real.

On March 23, 1998, Kenneth Starr subpoenaed the records of Kramerbooks, a store in Washington, to obtain a list of purchases by Lewinsky. One of the paperbacks Lewinsky was revealed to have bought—and given to Bill Clinton after reading it herself—was Nicholson Baker’s Vox, a novel about phone sex.

NICHOLSON BAKER: I was pleased—really totally surprised and flattered—to learn that Lewinsky had given the president her very own copy of my book. She was saying, I’m passing on my extremely personal page-turning experience to you. But the subpoena was just bad. Vox is a conversation between two people who are excited by the idea that they get to tell their private stories to each other. They get to tell stories and to be real to each other even while they have this artificial distance—they’re connected just by the phone. The book is trying to celebrate the secret hideouts that novels offer readers. And I love that about books. That kind of privacy ought to be respected.

On April 1, a judge dismissed Paula Jones’s lawsuit. (She appealed, and later settled with Clinton for $850,000.) Starr continued on, seeking testimony from several of Lewinsky’s fellow White House interns. Nicole Maffeo Russo, a former East Wing intern, was by then working in Boston. She flew to Washington to appear before a grand jury in April. Blumenthal, too, was called to testify before the grand jury (and was drawn into other legal actions).

Nicole Maffeo Russo: It was scary. I went down there not knowing what they wanted to talk about or why I was being subpoenaed. When I was in front of the grand jury, they asked me, “Well, what do you know?,” and I said, “I don’t know anything. I heard rumors and gossip.” And Starr’s team said, “Well, did you believe it?,” and I said, “Well, what does it matter what I believe?” I was very terse and snarky. I was a petulant child, really. But I would do it again.

I’m very proud of Monica Lewinsky for her anti-bullying campaign and for standing up for the #MeToo people—as someone who was one of the first people to go through it, she’s become a voice and a leader. If I could turn back time, I would’ve offered more support.

Sidney Blumenthal: Like others in the White House, I was subjected to right-wing suits from Judicial Watch, by Larry Klayman, who eventually sued his own mother. They were nuisance suits that nonetheless required you to have a lawyer and were attempts to create immense financial burdens and distract you and scare you. There was the Linda Tripp defamation suit. There was a suit from Bob Barr [a Republican representative from Georgia], in which he claimed that somehow information about his wife’s abortion had been leaked. There was no end to it. The legal bills all added up.

The first issue of Brill’s Content, a media-watchdog magazine, hit newsstands in June with a cover story by its founder and editor, Steven Brill, titled “Pressgate.” Brill quoted Kenneth Starr as admitting that he or members of his staff had selectively leaked information to the press—and took the press to task for running stories that advanced the independent counsel’s agenda.

Steven Brill: We were launching the magazine in June, and I decided by mid-January, late January, that the press around the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal really ought to be the lead story. The role of the press vis-à-vis the government had totally flipped since Watergate. Watergate was all about two reporters for The Washington Post—and then a lot of other reporters—not believing the prosecution’s version of things and refusing to be misled by Richard Nixon’s Justice Department. With Ken Starr, it was exactly the opposite: The press was the tool of the prosecution. The prosecution just kept leaking, and the press just kept lapping it up. In my view, Starr was also violating a statute related to grand-jury secrecy, which is now a little bit relevant because his deputy at the time was Brett Kavanaugh, and Kavanaugh was one of two people who were basically identified as leaking to the press.

In July, Lewinsky met with Starr’s team and reached an agreement under which she would be granted immunity for past statements in exchange for testifying to the grand jury. Lewinsky also agreed to turn over a blue Gap dress, which she believed (and DNA tests confirmed) was stained with the president’s semen.

David Brock had been a leading anti-Clinton reporter for The American Spectator but began to question his politics. He announced his change of heart in 1997 in an article for Esquire, “Confessions of a Right-Wing Hitman,” and began passing information to the White House about right-wing projects.

David Brock: From day one—literally the day after the election in ’92—there were people in my orbit who were actively talking about trying to thwart the Clinton presidency and get him impeached. So I was in a unique position. I don’t know how much of what I had was shared with Bill Clinton, but Hillary was getting these strings of information about what the right wing was up to. I had heard specifically that whoever the White House intern was—and I can’t totally recall that I even knew the name—she had evidence in the form of a dress.

Sidney Blumenthal: It’s hard to remember, but Bill Clinton was perceived as illegitimate in a lot of quarters when he was elected, and with immense suspicion and hostility. Some of it was because he had disrupted a long Republican era and all the relationships that had gone with that. Some of it was generational. There was a lot of antagonism toward Clinton as a representative of the ’60s generation.

“In his testimony, the president dodged and weaved. It’s very difficult to use harsh prosecutorial tactics on a president. You can’t yell at him. You can’t startle him.”

Mark Penn: Hillary wanted us to fight, fight, fight. We basically went back on campaign footing. That meant finding issues, finding communications, running the message, just like a campaign—but not about impeachment. The polling principle was: Keep the president’s approval above 50 percent at all costs, because above 50 percent, people are reticent to kick the president. Below 50, it’s to people’s political advantage to kick a political figure. That’s why a lot of people fall very quickly from 45 to 35.

We always had this distinction between public behavior and private life. In his public life he was an exceptional president. In his private life …

Lanny Davis: Hillary Clinton’s strength of character and her inner moral compass allowed her to survive what would have broken a lot of other people. She kept us all going even while we knew how difficult it was for her, far more than for us.

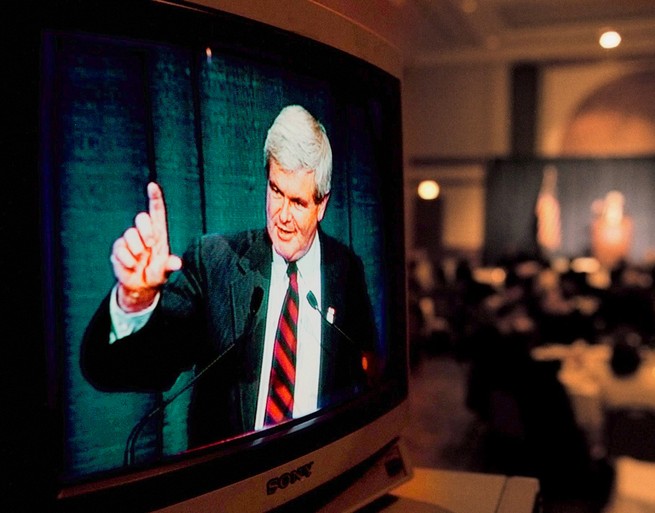

David Brock: I think Hillary Clinton’s Today-show appearance was critical in rallying first Democrats and then the rest of the public. You could see over time that the Clinton folks made a lot of headway in turning public opinion around to the idea that, even if something had happened between Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky, which we ended up finding out was true, nothing was on the level of an impeachable offense. That’s why [Speaker of the House Newt] Gingrich’s effort in ’98 ended up biting him in the ass.

III. THE APOLOGY SPEECH

On July 17, Starr served the president with a subpoena to appear before a grand jury. The subpoena was withdrawn when Clinton agreed to testify voluntarily. Starr made a number of concessions: Clinton would appear via closed-circuit TV from the White House, his testimony would be limited to one day, and his lawyers could be present.

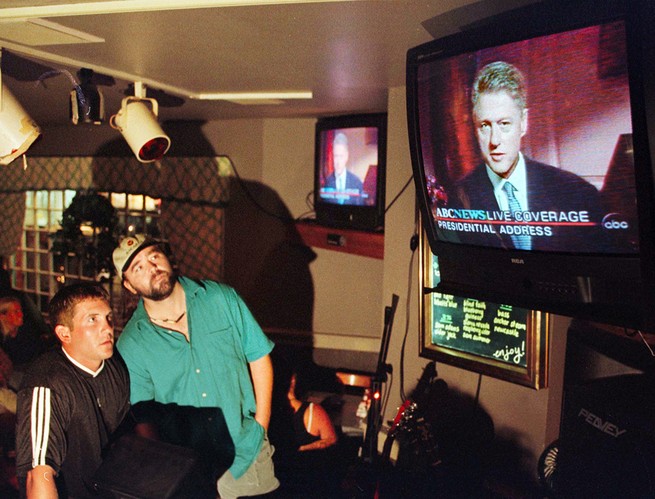

Clinton testified on August 17. Asked whether he had been truthful in affirming that “there is absolutely no sex of any kind” with Lewinsky, he answered, “It depends on what the meaning of the word is is.” That night, the president appeared on national television and expressed regret: “As you know, in a deposition in January I was asked questions about my relationship with Monica Lewinsky. While my answers were legally accurate, I did not volunteer information,” he said. “I know that my public comments and my silence about this matter gave a false impression. I misled people, including even my wife.” In the speech, he also angrily criticized the Starr investigation for overreaching and breaking ethical rules.

Paul Rosenzweig: In his testimony, the president dodged and weaved. It’s very difficult to use harsh prosecutorial tactics on a president. You can’t yell at him. You can’t startle him. We never got a very successful theory on how to counteract that. Most of the people that we get into a grand jury, they don’t have a time limit. We can say we’re going to stay here forever until you answer the questions. We can take them out in front of a judge and ask to hold them in contempt. Just looking at 23 jurors makes it hard to refuse to answer a question.

Mark Penn: The elites didn’t like the speech. I actually had an instant poll running, and the speech did fine. It did what it needed to do, and it also didn’t let down his supporters. I think people underestimate in these fights that the complete mea culpa deflates your supporters. So the mixture of “I did wrong, but, you know, there are also some other wrongs here” kept the flame going for a lot of people.

On August 20, the U.S. launched cruise missiles at what were suspected to be al‑Qaeda sites in Afghanistan and Sudan in retaliation for the bombing of the American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. The attacks invited comparison to the plot of a recent movie directed by Barry Levinson, Wag the Dog, about military action taken to deflect attention from a presidential sex scandal. General Anthony Zinni, the head of Central Command, oversaw that campaign, known as Operation Infinite Reach, as well as a second campaign, Operation Desert Fox, against potential weapons sites in Iraq, in December.

Anthony Zinni: The secretary of defense, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and I flew up to Camp David. The president was there—supposedly reconciling with Mrs. Clinton, as I understood it. We went through the options. And in the end the president kind of laughed and said, “I’m damned if I do and damned if I don’t.” Because there were two things that were coming out in the press at that time. One was the follow-on of the Wag the Dog movie—he would be doing this to distract. And the second was No, he won’t act—he’s been so weakened that he wouldn’t act. But really he gave the okay based on a full set of existing policies. He was not making a decision from a cold start. I think for the president to say “Let’s say not strike,” he would’ve violated all the policy that had been put in place.

Barry Levinson: David Mamet [one of Wag the Dog’s screenwriters] wrote a terrific piece of political satire that is just degrees off of what was possible. I had to go into the hospital for some minor surgery that summer. I was given some kind of painkiller. And the television was on and they were talking about the air strike and Wag the Dog. And I’m watching the TV in my slightly drug-induced state and saying, What?

IV. ARTICLES OF IMPEACHMENT

There was talk in Congress of impeachment at least as early as November 1997, when Representative Bob Barr moved to open an inquiry into foreign donations to Clinton’s 1996 reelection campaign. After the president’s apology in August, Republicans in Congress prepared to receive a report from Starr laying out possible grounds for impeachment. Julian Epstein was the chief Democratic counsel for the House Judiciary Committee.

Bob Barr: Everything changed with the revelation of the Monica Lewinsky incident. To me, this was unfortunate, because it took the focus away completely from what I thought, and continue to this day to think, were the far more serious and more substantive grounds for impeachment.

Julian Epstein: We were pretty sure by March, with all the overheated rhetoric from the Republican leaders, that they were going to impeach. I started making hires for impeachment staff in March.

Mark Penn: The question you really have in a crisis is: Can the business keep operating while you resolve the crisis, or not? If it can’t keep operating, then you have to dissolve it regardless of whether you’re innocent or guilty. If you can keep it operating, if you can make decisions and prove to people that you can supply the product or function, then even if you’re guilty on some of it, it’s okay. And that really became what the strategy was. The strategy was that he would do the job of president. He would talk about the other stuff as little as possible.

Several people on the independent counsel’s staff took a hand in drafting what came to be known as the Starr Report, which included a narrative of events and a legal argument, and was in places sexually explicit. Among the writers were Brett Kavanaugh and Stephen Bates. Bates, a lawyer and former literary editor at The Wilson Quarterly, now teaches at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. He contributed much of the narrative of events. David Kendall, a Washington attorney, represented Clinton on matters involving the independent counsel.

Stephen Bates: The idea was to do a factual summary in part to simplify things for the reader and also to have some indication of why you should believe Monica Lewinsky. And so that required including a lot of information about when she went to the White House, what time, how long she was there, what she heard with the president on the phone, that sort of thing.

Part of the point of including all that information was to bolster her credibility. Because on some of the crucial things, it was her account versus his account. She had an incredible memory. To the extent that the report is a story, it’s a story with an apparatus of footnotes or commentary. Like [Vladimir Nabokov’s] Pale Fire.

I recall only a few things left out of it, things that I thought were significant but that other people said shouldn’t be in there. One involved the fact that Lewinsky, as I remember, used Betty Currie to get material to the president—if she gave him a gift, it went to Betty Currie, and it was sort of a back channel. We knew the names of some other people who were on Currie’s list, including Barbra Streisand. I thought they showed that this is not just some starry-eyed intern; she’s part of a select group. Other people said, “You’re implying that there’s something sexual going on with Barbra Streisand,” which never occurred to me. So that ended up not making the cut.

David Kendall: The Starr Report made no attempt to summarize accurately the evidence the Office of the Independent Counsel had developed. A statement that remarkably was not included in the report was this one, from Ms. Lewinsky’s grand-jury testimony: “No one ever asked me to lie and I was never promised a job for my silence.”

On the afternoon of September 9, 1998, Starr’s deputy Jackie Bennett informed the House Judiciary Committee that two vans would soon arrive at the Capitol. They carried 36 boxes of evidence. Capitol Police officers conveyed the boxes to a locked room set aside for members of Congress. Starr’s team expected that, like the 1974 report on Watergate, assembled by Leon Jaworski, its work would remain confidential. Some Republicans, like Representative Bill McCollum, of Florida, felt that Democrats were never interested in a good-faith consideration of whether Clinton might be worthy of impeachment. Many Democrats believed the salaciousness of Starr’s report would work against it. On September 11, the House voted 363–63 to release the report to the public. Barney Frank was a Democratic congressman from Massachusetts.

Bill McCollum: You could go over there anytime you wanted, but it was basically under lock and key. Any House member could go. It wasn’t just the Judiciary Committee. One of the sad things about this, in my view, was that we couldn’t get Democrats to go read it—to go actually look at it. I don’t think they wanted to look at it.

“Starr used the compelled testimony of Ms. Lewinsky to paint a detailed, lengthy, and graphic account of their relationship. To what end? To humiliate and demean both people.”

Stephen Bates: We thought Congress would just use the report for their own purposes. When I was working on it, I got in touch with the National Archives and said I wanted to see Jaworski’s report from 1974, and they said you can’t. It’s still under judicial seal. During Watergate, the House Judiciary Committee was allowed to see it and nobody else, and it never went public.

In retrospect, I guess it was naive to think the same thing would happen in 1998. The only model we had was the Jaworski report, and how Congress treated that report as secret. And then Congress voted to release the Starr Report unread.

David Kendall: There was no need for Starr to send the detailed, pornographic report to Congress. In his grand-jury testimony in August 1998, the president had admitted that when he was alone with Ms. Lewinsky, he had engaged in conduct with her “that was wrong,” that did not constitute sexual intercourse but “did involve inappropriate intimate contact.” The president refused to answer further questions about this conduct, and Starr chose not to try to compel him to do so. The specific anatomical details were not relevant to anything, but Starr used the compelled testimony of Ms. Lewinsky to paint a detailed, lengthy, and graphic account of their relationship. To what end? To humiliate and demean both people.

Julian Epstein: The day we got that report, we knew it was over. We were certain of two things. One is that there wasn’t a strong legal case, either on perjury or on obstruction. The second thing was how much ammunition the report gave us—just the countless pornographic details and how unprofessional the work itself was from a legal standpoint. All this stuff about cigars and all the other gratuitous sexual things were absurd. The foolishness of Starr and the Republicans not to see how the sexual material in the report would backfire was just jaw-dropping to us.

Barney Frank: In September, Starr sends Congress a report—the congressional elections are in November—saying that the president has behaved badly and we can impeach him. He does not mention the other items he had been investigating, with one exception. Early on they had said that Vince Foster had killed himself—that the idea of murder was ridiculous. But the other three charges—Whitewater, the FBI files, and the travel office—were still pending, and people in opposition to Clinton were saying, “Oh, it’s all part of a pattern.”

After the midterm elections, when we had the hearing, before voting on impeachment, Starr said, “By the way, with regard to everything else I investigated, I have nothing negative to say about the Clintons.” So when I questioned him later, I asked why, before the election, he gave us the bad news about the subject he’d been investigating for only a few months, and withheld the good news until after the election. His answer was all mumbo jumbo. He said, “I can’t give you a date certain about how long before the election I knew.” I said, “Well, give me a date ambiguous.”

The decision to release the Starr Report created an opportunity for the fledgling publishing house PublicAffairs. Its founding editor, Peter Osnos, had been at Times Books and Random House and had pioneered a genre known in-house as “rabbits,” because they were pulled out of a hat: public-domain and political documents that cost nothing and could be published instantly. The PublicAffairs edition of the Starr Report was an immediate best seller.

Peter Osnos: It was announced on a Tuesday that it would come out on a Friday. I called The Washington Post and asked them if they would give us a disc of the report and the first-day Post coverage, which we could then use as the basis for the book. We struck a deal.

That was Tuesday. On Wednesday, David Kirkpatrick, who was then the publishing reporter for The Wall Street Journal—remembering the history of “rabbits” at Random House—called and said, “Are you thinking of doing a book?” And I said, “We are.” He wrote a story. We then heard from Amazon, which was still at its early stage but already significant, and they said, “Can you send us a jacket?” So we made a jacket, and we sent it to them. That was Thursday. Friday, the report was released, and we were in the newsroom of The Washington Post to pick up the disc. It was 8 o’clock. And I got a call from Bill Curry, the press guy for Amazon and a former Washington Post reporter. He said, “Congratulations, your book is now No. 1 on our best-seller list.” And I’m standing there thinking, Okay, this is a new world. I didn’t have the disc, there was no book, and we were No. 1 based on orders. Books started arriving in stores midday Monday, shipped by air.

Over the next several weeks, more evidence became public, including Clinton’s videotaped grand-jury testimony from August. Darrell Hammond’s impersonation of Clinton became a staple of Saturday Night Live during the impeachment process.

Darrell Hammond: In the videotapes, when Clinton was being questioned, he did the most interesting thing: He elongated his neck slightly, as a form of physical rectitude. Like, I’m not ashamed of anything. I’ve apologized for what I did, and I was right to do that, and I’d like to move on, and you’re really taking me away from presidential business.

When he got to engage these great legal minds in a debate over the meaning of the word is, that debate went on just long enough for the audiences I was playing for around the country, anyway, to decide this thing was just silly.

The biggest change in the media landscape as impeachment unfolded—and one that impeachment accelerated—was the emergence of the cable-news channels Fox, CNN, and MSNBC into a position of influence. Lanny Davis, having left the White House, became a constant presence on TV defending the president.

Lanny Davis: Given the legal concerns, there was no way the White House could put people on TV to discuss the Starr investigation. So that’s how I came to be the person who did so many cable-news shows, sometimes three to four times a day and night. I was now a private citizen and a volunteer to help the president. It was very difficult, physically and mentally. In August I had to go into the hospital because I had something called diverticulitis. After the operation, President Clinton called me and he said, “So what’s the condition?” I said, laughing, “I’m calling it ‘Clintonitis.’ ”

Lucianne Goldberg: I think I did 500 TV shows. I’d say, “I was on your show two weeks ago and told the whole thing.” They’d say, “Our audience can’t get enough.” My son was working the phones and said, “It’s Tom Brokaw! He says he wants to talk about oral sex.” I said, “I bet he does.”

Some aspects of the news media had not changed at all since the 1970s, including the recurring “Washington society is special and you have to know the rules” column. Sally Quinn of The Washington Post published one in the fall of 1998. She quoted the Post’s David Broder about Clinton: “He came in here and he trashed the place, and it’s not his place.”

James Carville: I can easily tell you what the high point of that whole time was. The high point was the Sally Quinn piece in The Washington Post where every fool was mouthing off about how Washington was a village and how dare the Clintons intrude on their turf. I don’t think she intended it this way, but she turned the tape recorder on and people just stood in line to make fools of themselves. No one could stop laughing at that. David Broder—just priceless.

Clinton remained popular with the public. After he denied an affair with Lewinsky in January, his Gallup approval rating spiked 10 points, to 69 percent. It remained in the 60s until the impeachment vote in December, when it shot up again, to 73 percent.

Lanny Davis: Everybody in the country got it in about a week. Bad judgment. Personal. Whatever you want to say. Nothing to do with abuse of presidential power. Nothing to do with the impeachment clause. He had publicly apologized to the country, to Ms. Lewinsky, and to his wife and family. It took all of Washington, including me, about a year to figure that out.

On October 5, 1998, the House Judiciary Committee voted to launch an impeachment inquiry, followed by the full House three days later. With less than a month to go until the midterm elections, Newt Gingrich decided to place the president’s misconduct at the center of the GOP’s campaign in television ads around the country.

Gingrich predicted that the Republicans would add significantly to their majority. Instead, the Democrats gained five seats in the House. Although the Republicans retained the majority, Gingrich was weakened and planned to resign his seat. Bob Livingston, of Louisiana, was expected to be elected the next speaker. Representative James Rogan, a California Republican, was a member of the Judiciary Committee.

Bob Livingston: We should have, when Clinton got into trouble, just not focused on his problems in the media. Had we really concentrated on our accomplishments in welfare reform, reducing taxes, and balancing the budget, we’d have had a lot to talk about. But we didn’t talk about them.

James Rogan: Suddenly the Republicans realized all this talk about impeachment almost cost them the majority. The speaker lost his job because of it. Within a day, I got a call from one of Gingrich’s people, who said, “You’ve got to make this go away. The speaker doesn’t want this to be the last thing on his watch.” Then, within, like, an hour, I got a call from one of Bob Livingston’s guys, who said, “You’ve got to try to make this go away. The speaker doesn’t want this to be the first thing on his watch.”

Barney Frank: It was always my view that Henry Hyde, the Judiciary chair, did not want to go ahead and press impeachment all the way, but Tom DeLay [the majority whip] was calling the shots and kept pushing them and pushing them.

As the Judiciary Committee began its inquiry, the typically rule-obsessed House had little sense of how to proceed. The Constitution lays out no specifics, and no president had been impeached since Andrew Johnson, in 1868. Members modeled the process on the Nixon investigation, a quarter century earlier. Charles Johnson was the House parliamentarian.

Charles Johnson: The rules governing the actions of the Judiciary Committee almost entirely mirrored what had gone on in the Nixon investigation. In ’74, things were getting pretty hot for Nixon. We had gone back to the journals of the Johnson impeachment, which were written in quill pen. We got them from Archives just to make sure we hadn’t missed anything. Of course, by the time articles of impeachment were ready to come to the floor, Nixon had resigned. Now, in 1998, the House was Republican, obviously, with Clinton, and had been Democratic with Nixon, but one basic thought that the leadership had was that they didn’t want the process, at least to the extent they could control it, to appear to be partisan.

On December 8 and 9, lawyers for Clinton pressed his case before the Judiciary Committee, arguing that, whatever Clinton’s transgressions, they did not rise to the level of impeachment. The White House presented as witnesses several veterans of the Watergate process as well as the Princeton history professor Sean Wilentz.

Sean Wilentz: I wanted to be as direct as possible about what the stakes were. There were still some House Republicans not on the committee who were on the fence, and I wanted to make it clear to them that impeachment was a terrible thing as far as the Constitution was concerned, that voting for impeachment for partisan or self-interested reasons was what the Framers had feared. I wanted to find some way to say that. So I put in a line about how “History will track you down.” It came from Congressman John Lewis. He and I had spent some time together two years before, for an article I wrote, and at one point I asked him why he thought he had done what he’d done in the ’60s. He said, “Well, you know, history just tracked me down. History tracked me down.” It stuck in my mind.

When I adapted the phrase in front of the Judiciary Committee, I could see off in the corner that the Republican staffers were really very riled. Afterward—from Lewis’s office, in fact—I called the White House to get their reaction, see what they thought of what I’d said. Sid [Blumenthal] told me, “Well, some people thought you were a little over the top, but it was good.”

The Democrats sought to strike a deal to censure Clinton instead of impeaching him. It was ruled out of order. On December 11, the Judiciary Committee voted essentially along party lines to send three articles of impeachment to the full House, and added a fourth the following day.

The first article alleged that Clinton had committed perjury by lying to the grand jury in August about his relationship with Lewinsky, and in prior false statements. The second alleged that he had also perjured himself in his January deposition in the Jones case. The third accused him of obstructing justice—coaching Lewinsky and Betty Currie on their stories, concealing gifts he had received from Lewinsky, and attempting to find her a job. The fourth alleged that he had abused his office by attempting to stonewall the impeachment inquiry.

Hearings in the full House were scheduled for December 17, but were delayed for a day when Clinton launched air strikes against Iraq—prompting renewed outrage and Wag the Dog analogies.

Caroline Self spent her White House internship working for Betty Currie. She, too, had been called to testify before the grand jury. Self returned to Harvard to finish her degree but arranged to visit Currie on December 18, on her way home to Alabama for Christmas—the day before the impeachment vote, when televised debate was in full swing.

Caroline Self: On my way in, I saw a friend and said, “What’s it like in there?” She said, “It’s like a morgue.” I went to see Betty. I saw the president. He said hello, and then he asked Betty to turn up the volume on the TV. Then we watched the impeachment debate on the TV. Talk about surreal. He was very engaged, but he wasn’t dwelling on it. I think it’s probably one of those things that, if he was okay, he hoped other people would be okay. I wonder what he was really feeling.

In October 1998, Hustler’s publisher, Larry Flynt, took out a full-page ad in The Washington Post offering $1 million to anyone who could prove they had had “an adulterous sexual encounter with a current member of the United States Congress or a high-ranking government official.” Flynt also had his own investigators dig for dirt. Outwardly, Washington laughed. “I’d like to commit adultery so I could get the $1 million,” Representative Alcee Hastings, a Florida Democrat, told the Post. Privately, some members were nervous. Gingrich, while married, was conducting an affair with his now-wife, Callista. Several representatives confessed to earlier extramarital affairs, including Henry Hyde, Helen Chenoweth, and Dan Burton, who had become infamous for shooting at melons in his yard in a bid to prove that Vince Foster had been murdered.

Around midnight on December 15, a staffer called House Speaker-designate Bob Livingston and said Flynt had turned up affairs of his from years earlier. On December 19, Livingston told a shocked House that he would not stand for speaker and planned to resign. “I can only challenge you in such fashion if I am willing to heed my own words,” he said. Representative Ray LaHood was presiding over the impeachment hearing.

Bob Livingston: For more than two decades, I’d worked to establish a very fine career in Congress, unblemished, and all of a sudden the bottom fell out. Flynt was sitting there holding all the cards. I had heard that he’d had some success with other people. I just didn’t think it was going to be me. To sweep it under the rug would have meant a total catastrophe on the opening day of Congress. And I couldn’t do that to my colleagues, I couldn’t do it to the party, I just couldn’t do it to anybody else.

It was raucous when I called on Clinton to resign, told him that it would be painful but that other people had done exactly what he had done and had gone to prison for it. That’s when the Democrats just went nuts—“You resign!”—and I would say not all Democrats, but certainly a lot of them. And then I just put my hand up and carried through with my own resignation. There was a pall. There was a lot of quiet.

Ray LaHood: The air went out of the chamber. John Conyers, who was the ranking member on the Judiciary Committee, came up to the podium and said, “Do you think we should suspend the debate?” And I made a very quick decision and said, “Absolutely not. We are going ahead with this. This is what we’re supposed to be doing.”

Charles Johnson: Ray LaHood was in the chair, and members, really responsible members on the Democratic side—Vic Fazio, I remember, and Mel Watt, two or three others—came up and urged LaHood to run as a caretaker speaker. I can remember him telling them he wasn’t going to do it. Several hours later, Denny Hastert’s name emerged on the floor while the debate resumed on the articles of impeachment. Hastert emerged from nowhere.

Larry Flynt: It was hypocrisy up to his eyeballs. I remember somebody asked Livingston what he thought of me and he said, “I think he’s a bottom feeder.” Somebody asked me for comment and I said, “Well, that’s right, but look what I found when I got down there.”

James Carville: Clinton was lucky in his choice of enemies. I mean, you look back and you just can’t help but laugh out loud. Dan Burton shooting melons in his backyard. Some of these people were just unbelievable. And we forget how unpopular Gingrich was at the time.

David Kendall: Starr has complained that a country enjoying peace and prosperity just couldn’t properly understand the Clintons’ many misdeeds. There’s an alternative explanation for the public’s distaste for impeachment: The focus on President Clinton’s affair with Ms. Lewinsky also brought to light a number of frisky Republicans—Newt Gingrich, Henry Hyde, Bob Livingston, Dan Burton, and Helen Chenoweth, to name a few. The public reasonably concluded that the drive to hound the president from office was both hypocritical and an overreaction.

“We had maybe half the Senate standing along the back rail of the House chamber watching the vote. There was just absolute, utter shock … they were apoplectic: ‘What’re we going to do now?’ ”

The House voted in favor of two articles of impeachment, finding that Clinton had committed perjury before the grand jury and had obstructed justice, but rejected accusations of perjury in the Jones case and of abuse of office.

James Rogan: I don’t think any of us believed that Clinton would actually be impeached until the very, very end of the process. I just never believed it was going to happen.

Ray LaHood: When the votes were taken—and I announced each one separately—I think people were surprised by the fact that Clinton was impeached by the House but not on all four impeachment articles.

Barney Frank: One thing that never got enough attention was that the impeachment process was conducted by a lame-duck Congress. If the Congress elected in 1998 had voted, instead of the one that did vote, one of the articles would not have passed the House, because there were a number of pro-impeachment people who were defeated by anti-impeachment Democrats. Some weirdo from New Jersey was defeated. He was the one who sang on the House floor, “Twinkle, twinkle, Kenneth Starr, now we see how brave you are.”

James Rogan: We had maybe half the Senate standing along the back rail of the House chamber watching the vote. There was just absolute, utter shock. I walked by a bunch of them, and they were apoplectic: “What’re we going to do now?” I said, “Well, you’re going to have to try the case, that’s what you’re going to do now.”

V. THE TRIAL AND ITS AFTERMATH

Once Clinton was impeached, it fell to the Senate to put him on trial and decide whether to remove him from office. The trial was set to begin on January 7, 1999. Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott called Minority Leader Tom Daschle and said he wanted to work out the process. One of their decisions was to host executive sessions for the full Senate, with no media present. They chose to meet in the Old Senate Chamber, which had housed the Senate until 1859 and then for decades was the home of the Supreme Court.

Tom Daschle: Henry Clay, John Calhoun, and Daniel Webster spent their careers in that chamber, so there’s just an awesome feeling of history. In the public sessions, people were speaking to the camera, but in the executive sessions people were speaking to each other. They were very candid, very emotional sometimes.

We had one question in particular about how we were going to proceed. [Senator] Phil Gramm made some proposal and almost immediately Ted Kennedy agreed with that, and we were so enamored of the fact that you had Ted Kennedy and Phil Gramm finding some consensus that we said, “Do you all share that view?,” and everybody said, “Yeah.” Walking out, Trent and I felt we needed to make an announcement that, procedurally, this is what we were going to do. Trent said, “Do you understand what we actually agreed to?,” and I said, “No, I thought you did.”

James Rogan and Bob Barr were among the 13 House Judiciary Committee members selected as managers for the Senate trial—in effect, prosecutors. They worked with the Republicans’ chief investigator, David Schippers, to negotiate a process with the Senate.

James Rogan: Trent Lott did handsprings trying to make it go away. Lott finally told Schippers and me, and this is about as precise a quote as I can give you, because it still rings in my ears, “We don’t care if you have photographs of Clinton standing over a dead woman with a smoking gun in his hand. I have 55 Republican senators, seven of whom are up for reelection next year in very tough races. You guys in the House just jumped off a cliff. We’re not following you off the cliff.”

Bob Barr: They didn’t want to have anything to do with an impeachment. The procedures were, from the standpoint of a trial attorney, laughable. We could call no live witnesses. They limited the overall evidence that we could use to only that evidence which already was in the public domain. So they made it impossible for us to present a strong case.

Tom Daschle: If witnesses had been called, it would have been far more sensational, and we wanted to keep the sordid nature of some of this out of the public spectacle, to the extent we could. I think we always knew we had the votes not to convict. What I was more concerned about was ensuring that at the end of the day not one senator would say, Well, if I only had known this, I would have voted differently.

David Kendall: The president apologized repeatedly for his conduct and to Ms. Lewinsky. At a White House prayer breakfast on September 11, 1998, he said, “I have done wrong,” and “I don’t think there is a fancy way to say that I have sinned.” He apologized explicitly to “everybody who has been hurt,” including “Monica Lewinsky and her family.” The Starr Report came out later that day. In every pleading we filed in the House and Senate, we repeated this apology, and on behalf of the president, my partner and I apologized directly and personally to Ms. Lewinsky in January 1999, when her deposition was taken by the House managers as part of the Senate trial.

After arguments in the Senate concluded, on February 9, senators repaired behind closed doors to deliberate. When they voted, on February 12, both articles were defeated. Forty-five senators voted to convict on perjury, and 50 on obstruction—well short of the 67 needed to remove Clinton from office. Shortly after the vote, the Capitol had to be evacuated because of a bomb scare. Some Democrats went to the White House to meet with Clinton.

Tom Daschle: Within an hour after I had voted on impeachment, I was walking around the Air and Space Museum, because we all had to clear the building and we had no place to go.

Julian Epstein: Clinton certainly felt the scarlet letter of impeachment. He was embarrassed and ashamed, for sure, and he felt like it had really hurt his second term. But he thought of himself as the Comeback Kid. I think he felt good about being vindicated. I think he felt good about beating Starr. He’s generally a pretty upbeat person, and he definitely was that day.

The day after the acquittal, Saturday Night Live featured Darrell Hammond as a triumphant Clinton in the White House Rose Garden.

Darrell Hammond: You had this person who was, you know, sort of a scallywag, but only on about a Daffy Duck level. He was the kid who’d been sent to the principal’s office but now was back, and he was okay. He didn’t get a paddling, he didn’t get a suspension, he didn’t get after-school detention. He was sprung free.

And once that happened, the first thing we did on the show was have him walk out there and say, “I am bulletproof.”

Bill McCollum: It was all about the rule of law. Henry Hyde said those words over and over again, and people wondered, What in the world are you talking about? The rule of law is about the public’s faith in the court system, in the law. When you have a president who violates the law in court, in a deposition or in front of a grand jury, and you don’t hold him accountable, that undermines the faith people have in the court system. It wasn’t about the actual underlying facts of what happened in the White House or about Monica Lewinsky. It was about upholding that rule of law.

Lucianne Goldberg: This guy was a horndog. We chopped him alive. He never was the same. I don’t care whether he got impeached or not. I just wanted people to know what kind of person he was.

Privately, some Democrats felt the party would be better off if Clinton resigned and allowed Al Gore to become president ahead of the 2000 election. Despite Clinton’s high approval ratings, his personal reputation was tarnished, and Gore distanced himself from Clinton during the campaign. He narrowly won the popular vote but lost in the Electoral College after the Supreme Court intervened in the Florida recount.

James Rogan: Eddie Markey, who’s now a senator from Massachusetts, came up and put his hand on my shoulder and whispered to me, “You know, Jimmy, truth be told, we should all be impeached for perjury.” And I said, “What do you mean?” And he said, “Because you Republicans want the son of a bitch to stay and we Democrats want the son of a bitch to go.” What he meant was that Republicans were better off in the 2000 election with a tarnished president that Vice President Al Gore had to defend, whereas it would be far better for the Democrats nationally in 2000 to have Clinton just go away and have Gore sworn in as president.

Robert Shrum: Without the Lewinsky episode, I don’t think there’s much doubt that Al Gore would’ve won the election. Basically, Bush’s pitch was that he wasn’t going to change much of anything except that he was going to give a tax cut to people to share the prosperity. The central thing, however, that he said he was going to do was restore honor and dignity to the White House, and that was code for everything that had happened. The Bush appeal was very clever, I have to say.

Robert Bennett: I often think, Would it be different representing President Clinton now? Would Clinton have survived among today’s attitudes? In the Clinton era, I had all these women—Cabinet officers—I went out and talked to many of them, talked to Patricia Ireland of now. There were many women who liked his politics, so they gave him the benefit of the doubt. Now would they believe him? I don’t know.

David Brock: The fact that there is a group of organized Clinton haters out there is one thing the Clintons took forward. It played out in the controversy over Benghazi, it played out in the controversies over the Clinton Foundation. Donald Trump’s closing argument in 2016—“Lock her up”—was something that had been seeded more than 20 years before.

Impeachment had failed, but a criminal investigation was still open. One issue was whether Clinton had lied under oath. A sitting president was unlikely to be indicted, but a president could face legal action after leaving office. Kenneth Starr left his job as independent counsel in 1999 and was succeeded by Robert Ray. As the Clinton administration neared its end, the president and his lawyers sat down with Ray to sign a final agreement ending the independent counsel’s investigation. The president admitted to “testifying falsely” in his January 1998 deposition, agreed to pay a $25,000 fine, and surrendered his Arkansas law license. Ray had met Clinton only once before—shaking hands on a rope line at the Army Navy Country Club, where both were playing golf.

Robert Ray: Around the holidays—Christmastime 2000—there was a meeting between myself, my chief of investigations, and my deputy, together with the president, David Kendall, Nicole Seligman [another Clinton lawyer], and the White House counsel, in the Map Room of the White House. It was done after hours, at night, after the last candlelight tour left the White House. It was after 10 o’clock.

The purpose of the meeting was for me to speak to the president without any filter and say, “Listen, in the best interests of the country, this is what I’m prepared to do so long as you’re prepared to do the following things that I ask. It’s not negotiable. If you do those things and you accomplish them all before you leave office, I am prepared to forgo prosecution.” The things I asked for included acknowledgment in writing of false testimony under oath; agreement to resolve matters with the Arkansas bar, which resulted in the suspension of his law license for five years; and agreement to forgo claiming legal fees in connection with the independent counsel’s investigations. And he did what I asked. That was the resolution that was announced on January 19, 2001.

When I was getting up to leave—everybody was kind of saying their goodbyes—I heard a voice. I wasn’t completely paying attention; I was distracted. Then I realized it was the president talking to me. He said, “Been out to play golf anytime recently?”

On Christmas Eve 2017, Monica Lewinsky ran into Kenneth Starr at a restaurant in New York City. They had never met before. Lewinsky is now a writer and an activist. As she recounted in an article in Vanity Fair, she said to him, “Though I wish I had made different choices back then, I wish that you and your office had made different choices, too.” In reply, Starr called the situation “unfortunate.” He made no apology.

This article appears in the December 2018 print edition with the headline “The Inside Story of the Clinton Impeachment.”

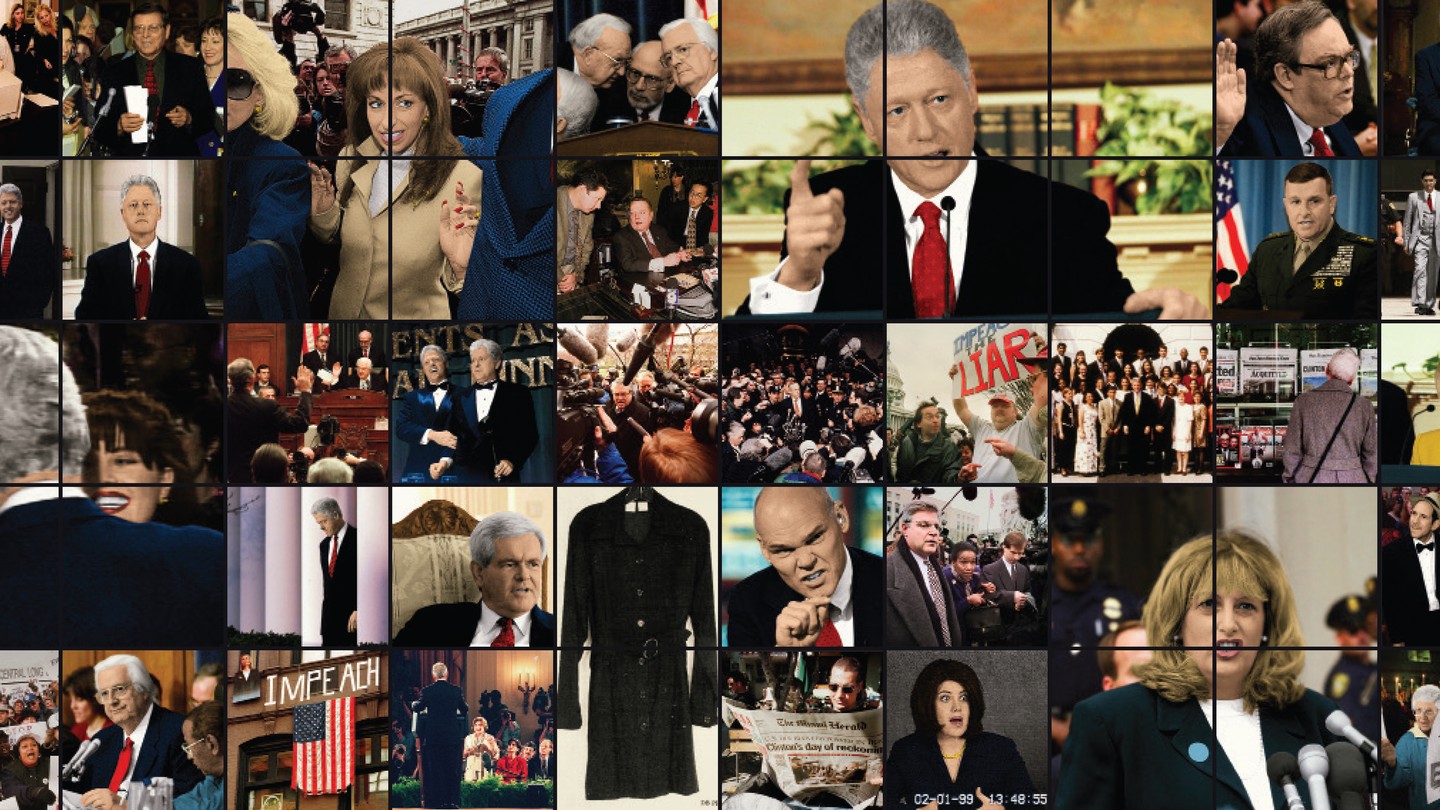

* Illustration: Gluekit; photos: Associated Press, CNP, Getty, Reuters; Bob Galbraith, Chris Pizzello, Colin Braley, Doug Mills, Greg Gibson, J. Scott Applewhite, Joe Marquette, Joel Rennich, Joyce Naltchayan, Kevin LaMarque, Kevork Djansezian, Khue Bui, Luke Frazza, Mark Wilson, Peter Morgan, Ron Edmonds, Stephan Savoia, Wilfredo Lee, William Philpott, Win McNamee