- "His unshowy prose has genuine immediacy. He's good company on the page," said the New York Times' reviewer of John Moynihan's "The Voyage of the Rose City."

When 20-year-old John Moynihan went to sea, it was with his mother's enthusiastic blessing.

In contrast, his father, who'd worked on New York City's docks and had served in the navy during World War II, gave his consent reluctantly.

The planned 45-day stint with the merchant marine became four months and the journal he kept was turned into a book-length writing assignment required by Prof. Paul Horgan at Wesleyan University. The father was delighted when he read about life aboard the Rose City, an oil supertanker that crossed the equator, went around Africa and headed for Japan. The mother, who'd initially been swept up by romantic notions of the sea, should have liked it, too.

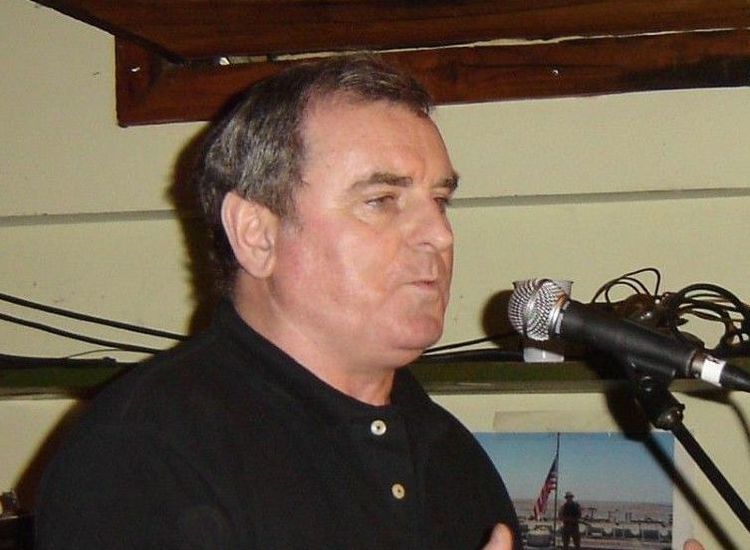

"But when I tried to read it, I was appalled. How could I put my child at such risk?" Elizabeth Moynihan said of her son's seafaring adventure in the summer and fall of 1980.

She came across the manuscript more than 20 years later when grieving for both her husband and their youngest child, who had died in 2003 and 2004. Former U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan was 76 and John McCloskey Moynihan, 44.

"I kept rereading it. I thought it was wonderful," she said of John's account. "So well-written and so honest – not in any way judgmental or condescending. How did he hit that tone so right when he was 20 years old?"

She undertook to have it published privately - just 100 copies for family and friends.

"Liz was not going to rest until her son John's vivid account of life on the Rose City lived as a book in some form," said her friend the documentary filmmaker Jennifer Callahan.

"It never occurred to me that a commercial publisher would be interested in it," Moynihan said, holding one of the limited-edition copies close to her.

But word got out, and Spiegel & Grau, a division of Random House, was very interested indeed. Moynihan took it to a lawyer, who advised a lot of changes on legal grounds. "I said to this fellow: 'If Herman Melville had come to see you, "Moby Dick" would never have been written,'" she recalled. In the end, only names were changed, while all the other details, such as the ethnic backgrounds of the individuals depicted, stayed in.

"'The Voyage of the Rose City' deserves its wider audience," said the reviewer Dwight Garner in the New York Times, when it was published a few months ago. "His unshowy prose has genuine immediacy. He's good company on the page."

Planning a move

Moynihan would continue to write, while making a profession for himself in animation. However, the industry was increasingly based in Los Angeles, and he'd never liked the West Coast.

He loved Sydney, Australia, and after his marriage broke up decided to begin a new life there. After several trips, he finally won a work visa in 2004. He passed the medical examination in October of that year and began preparations for the move.

Then while packing boxes in his Florida home, he pulled a muscle. The pain medication he took left him gravely ill with liver failure.

His older brother Tim found a bottle of Tylenol on a counter in his apartment; about eight were missing. John had had a suspected case of hepatitis as a 12-year-old in India, when his father was serving there as U.S. ambassador, and that was likely a factor in the acetaminophen reaction, family members believe.

Only a massively expensively transplant could save him. A friend of his mother's underwrote it to speed up the process and a suitable liver was flown from Puerto Rico.

Elizabeth Moynihan and her younger son were always particularly close. "We'd send each other stories or poems or funny things," she said. Whenever there was a full moon, they’d find a way of making contact no matter where they were in the world. That wasn't easy if she was in India, which she has visited 40 times doing research on the Moghul gardens.

In what was just one of the many coincidences connected with her son's death, she said, she noticed that one of his nurses, a petite Hispanic woman, had a gold chain with her name, Selena. She told her that her ill son lying on the bed between them had been a Greek mythology major, and that the Greek goddess for the moon was Selene.

"She hadn't known that," Moynihan said.

The stricken man's mother began to have doubts that his having a transplant was the best course.

"You live on a cocktail of antibodies for the rest of your life. You're so vulnerable to infection," she said. "John was a person who traveled his entire life. He went to the wildest places in the wildest ways, and managed. He would never be able to do that."

Though she had no way of knowing if he could hear her, she said to him: "You have to forgive me. I think I have made a mistake in your having this operation. I don't think you would like that life you would have.

"I didn't know what else to do. I wanted to save your life. And I love you.

"And I said the strangest thing to him: 'If you don't want to do it, don't do it.'"

The operation was to be eight hours and Moynihan was told she'd be called in about five hours.

"So I went back to the hotel," she continued, "and when I walked in the room, the phone rang and it was a nurse saying the doctor wanted me to come back. I knew he was dead."

After the funeral and cremation, his mother brought his ashes to Australia. "I could see he would have had a wonderful time in Sydney," she said. "He had nice friends. It's a terrific city. It wasn't escaping; it was a totally positive thing.”

She added about her son: "He was one of those people who made life interesting for people who were around him.

"His father was that way – he was that way until Kennedy was killed," Moynihan said. "His famous quote to [journalist] Mary McGrory – that was his life."

Pat Moynihan, who was under-secretary at the Department of Labor, said to the Washington Star reporter: "I don't think there's any point in being Irish if you don't know that the world is going to break your heart eventually. I guess that we thought we had a little more time.

His wife finished the story. "Mary said: 'We'll never laugh again.' And he said: 'Oh yes, Mary, we will, it's just that we'll never be young again.'

"Pat had a wonderful gift - a marvelous ability to describe something memorable. 'Defining deviancy down’ – you know, that kind of thing," Elizabeth Moynihan said. "In a speech or an article he could describe a problem that most of us hadn't recognized yet in a way that most people could understand.

"It got him in trouble," she added.

Pat Moynihan and Liz Brennan, a Massachusetts native, met while working on the staff of New York Gov. Averell Harriman in the latter half of the 1950s. Unlike her future husband, whose maternal side was of mixed heritage, her background was 100 percent Irish. But while his grandfather was born in Ireland, and he was in contact with relatives there, the various branches of her family have been longer in America.

The county dinner

She was always interested in politics and the Democratic Party. She first met Bobby Kennedy, for instance, when a friend of hers was working on his brother's congressional campaign. (She later worked for RFK when he successfully sought to represent New York in the Senate.)

"Worker bees have a very good time, and I'm a worker bee," she said.

"In some cases, they would have preferred me," she remembered about the backroom politicos' attitude towards her husband, "because what they wanted to know was: 'Is he coming to the county dinner?'

"Politics was not his passion; government was his passion," Moynihan said of her husband, who wrote more than a score of scholarly books.

Michael Barone, the editor of "The Almanac of American Politics," described him as "the nation's best thinker among politicians since Lincoln and its best politician among thinkers since Jefferson."

The fact he was so intellectually respected was perhaps one reason that he could get by with what his widow described as a "mom and pop campaign."

"For us, it worked," she said in her Central Park West apartment, which contains all of her and her late husband’s papers and possessions.

Hillary Clinton raised more than double the amount of cash in her successful campaign to succeed him than he did in his entire 24-year Senate career, and her Republican opponent outspent her.

"Money has ruined politics," Moynihan said.

Washington could do with a Daniel Patrick Moynihan now, she believes. Someone who worked for four consecutive presidents before seeking elective office could bring people together.

"Senators don't know each other; their families live at home," she said.

Moynihan began her own distinctive scholarly career in India in 1973. She wrote a survey of surviving Moghul gardens, which was published six years later as "Paradise as a Garden in Persia and Moghul India." She researched Babur, the founder of the Moghul dynasty, and she located and documented four previously unknown 16th century gardens built by him. Earlier this month she returned to New York from her latest visit, which lasted eight weeks.

"Liz is brilliant, creative, determined, generous and altogether super-amazing," said Callahan, the director of "The Bungalows of Rockaway."

Elizabeth Moynihan was tapped 20 years ago to be a trustee of the Leon Levy Foundation. Its main achievement, she said, has been the creation of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, a graduate school at NYU.

Moynihan's other important interest is her family, her two grandchildren in particular. Her daughter Maura's son, Michael Avedon, has lived with her since childhood. The 21-year-old student, who bears a striking resemblance to his late uncle at the same age, has inherited an interest in photography from his other grandfather, Richard Avedon.

Her son Tim and daughter-in-law Tracey, who is from an African-American family in Pennsylvania, have a daughter Zora, a freshman in high school in Brooklyn.

Her younger son, though, whom she remembers simply as a "great kid," is never far from her thoughts.

Elizabeth Moynihan remembered that a proud father sent his son's work to his friend William Shawn, the editor of the New Yorker. It was turned down, like most submissions to that magazine, but Shawn said: "This young man can write and should continue to write."

Thirty years on, the New Yorker said: "The book is a remarkable portrait of youth, and the ultimate fate of the Rose City is as surprising as Moynihan's choice to ship out in the first place."

The Rose City was decommissioned and became a hospital ship, and was the first that arrived in Haiti after the earthquake.

"He would have loved that," said the author's mother.

“The Voyage of the Rose City” is published by Spiegel & Grau ($22).