Just before the 2009 Houston mayoral runoff election, 35,000 postcards were sent to houses across the city showing one of the candidates, Annise Parker, being sworn in as city controller next to the woman who is now her wife. The caption asked, “Is this the image Houston wants to portray?”

Houston voters answered “yes” on Election Day, making Parker the first openly gay mayor of a big American city, the most populous in Texas.

While her election surprised many non-Houstonians, Parker remembers being the city’s safe candidate. After all, she had 12 years of experience as a city official and was running against a man who had never held public office.

When she left office in 2016, Parker was the top-ranked mayor in the U.S. by the City Mayors Foundation. She now runs the Victory Fund and Victory Institute — sister organizations dedicated to helping LGBTQ candidates win elections.

Even a decade ago, being an openly LGBTQ candidate was typically a “deal breaker,” according to Brian Harrison, a political scientist at Northwestern University. “That’s changing,” he said, noting “being LGBTQ isn’t nearly the liability that it used to be.”

Still, there are only 559 known openly LGBTQ elected officials in the U.S., just 0.1 percent of elected officials nationwide, according to a new Victory Institute report. To achieve proportionate representation, America’s estimated 11 million LGBTQ adults (roughly 4.5 percent of the adult population), would need to hold nearly 23,000 more public offices, a 4,000 percent increase, according to the report.

“We’ve come a long way since the first out elected officials assumed office in the mid-’70s,” Parker told NBC News. “But we still have a long way to go, certainly to achieve parity in representation, but also a long way to go to fully secure our rights.”

A SEAT AT THE TABLE

Just one LGBTQ official could change a room’s political atmosphere, according to recent research and several lawmakers’ anecdotes.

In a 96-country survey by the LGBTQ Rights and Research Initiative at the University of North Carolina in 2013, researchers scored countries on their LGBTQ equality policies using an eight-point scale. Countries with at least one LGBTQ parliament member scored 3.3 points higher than those without, and those nations were also 14 times more likely to have marriage equality laws.

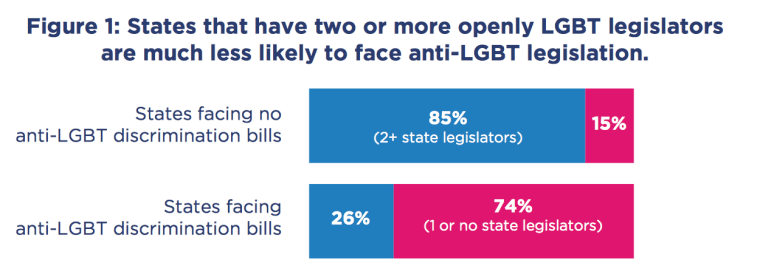

This same pattern was also observed when comparing U.S. states, according to a 2016 Victory Institute study. After the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 2015 ruling legalizing same-sex marriage nationwide, anti-LGBTQ legislation was disproportionately introduced in states with low LGBTQ representation. In the 30 states that faced anti-LGBTQ legislation after the ruling, nearly 75 percent of them had one or no out LGBTQ state legislators. However, in the 20 states that did not face such legislation, 85 percent of them were found to have two or more LGBTQ state legislators.

“Just having someone in the room who’s a member of the community changes what people are going to be willing to say,” according to Melissa Michelson, a political science professor at Menlo College in California. “It’s going to lead to people changing the way their votes are going.”

Leslie Herod, a Democrat who in 2016 became the first African-American LGBTQ person elected to public office in Colorado, agrees. When her friend, fellow Colorado state legislator Stephen Humphrey, a Republican, co-sponsored a bill that would allow business owners the right refuse service to LGBTQ individuals for religious reasons, Herod said she opted for a face-to-face conversation.

“I looked him in the eye and I said, ‘I know you’re not this hateful person they’re making you out to be," Herod recalled. "I don’t know why you’re carrying this bill, but I know that you would not be OK if I came to dinner in your district, and they refused to serve me because I was black or because I was gay.’”

Herod said she then asked Humphrey, “Why would you want to create a climate right here in Colorado where that would be tolerated?”

Herod said Humphrey then explained to her that his intention was not to discriminate against people. “I believe him,” she said, adding that the bill was eventually postponed indefinitely.

Personal interactions with constituents also have the power to change the hearts and minds of lawmakers when it comes to LGBTQ issues.

For example, South Dakota Gov. Dennis Daugaard, a Republican, supported a 2016 bill that would have required transgender students to use bathrooms and locker rooms that matched their sex at birth, not their gender identity. However, after meeting with trans students and hearing their stories, he changed his mind and vetoed the legislation.

“If you don’t know anyone who’s ever lost their health care and has had to go bankrupt because they can’t afford their medical bills, you probably aren’t as empathetic to the needs to health care reform,” Harrison said. “Similarly, if you don’t know any LGBTQ people, you are less aware of the need for change.”

While the focus tends to be on bigger national races and members of Congress, Parker stressed the importance of LGBTQ representation at the state level, because states incubate the most discriminatory bills. According to the Victory Institute, 13 states have zero openly LGBTQ legislators.

UNDERREPRESENTED AMONG THE UNDERREPRESENTED

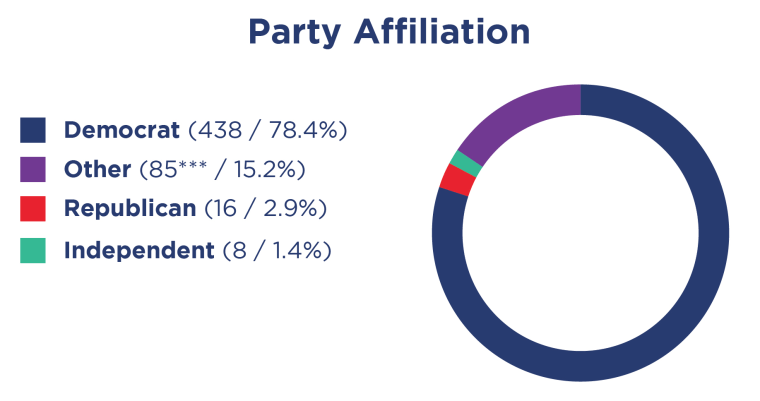

Even among the 559 openly LGBTQ elected officials, representation is not proportional. The vast majority of them, according to Victory Institute’s report, are gay, white, male and Democrats.

People of color make up just 20 percent of the LGBTQ-held offices, according to the report. However, they make up nearly twice as much of the nationwide LGBTQ population — 39 percent, according to the Williams Institute, think tank at the UCLA School of Law.

“Bias and discrimination are additive,” Harrison said. “People of color in particular, but also lesbians, bisexual and transgender people, experience discrimination not just because they’re LGBTQ, but because they are a segment of the community that isn’t as well-regarded or publicized.”

Herod, who represents northeast Denver in the Colorado General Assembly, said the lack of successful minority predecessors can scare candidates from even running.

“When I initially considered running for office, I didn’t know that I could do it,” she said. “I didn’t know that I would have the support of the community … because I never saw anyone who looked like me in elected office, no one who held my identity serving in Colorado.”

One year after Herod was elected in Colorado, Christy Holstege won a seat on the Palm Springs City Council, the first all-LGBTQ city council in the nation. But even in Palm Springs, California — which ranked third in the U.S. for the number of same-sex couples per 1,000 households — Holstege said her bisexuality sparked negative attention.

“There is erasure and invisibility discrimination,” Holstege said. “I mean, even just this week I got a Facebook message from a constituent asking how I could be part of the LGBTQ community if I’m married to a man, which I am.”

Holstege said during her 2017 campaign, endorsement and media interviewers asked her highly personal questions about her sex life, inquiring as to whether she had any bisexual “experience” or whether her sexual identity was “merely hypothetical.”

“I don’t think we would ask that of lesbians or gay men,” Holstege said. “We just don’t require that work for people with less marginalized identities.”

Bisexual officials hold only 2.7 percent of LGBTQ-held offices, according to the Victory Institute, but they make up approximately 50 percent of the national LGBTQ population, a 2011 Williams Institute study estimated.

Holstege said her straight friends were more supportive of her run for office as an openly bisexual candidate. She said it was “much harder to get support and validation” from others in the LGBTQ community. “It hurts much more, because you feel that those are safe spaces,” she lamented.

Transgender elected officials make up about 2.3 percent of all known openly LGBTQ elected officials, according to Victory Institute, which found that their numbers had doubled in the past year, from six to 13. The most high-profile among the newly elected trans officials is Danica Roem, who in November beat a long-time Republican incumbent for a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates, becoming the first openly transgender person to be seated in a U.S. state legislature.

But even though transgender elected officials have gained ground, Harrison said prejudice against trans people is still widespread — both within and outside the LGBTQ community

“Transgender identity is seen by many as being performative, that it’s not a legitimate identity,” Harrison said. “It certainly is not true,” he added, but he said some people still “have visceral discomfort with the idea of a transgender person.”

Another group underrepresented among the the 559 openly LGBTQ elected officials are Republicans. While an estimated 14 percent of LGBTQ people voted for the Trump-Pence ticket in the November 2016 election, Republicans represent less than 3 percent of LGBTQ elected officials, according to the Victory Institute report.

“The party cue has turned back to being very anti-LGBTQ,” Harrison said. “I think if you’re an LGBTQ person, it’s harder and harder to justify why you’re using that party label.”

A ‘RAINBOW WAVE’

More than 400 self-identified LGBTQ people are running for office this election cycle, a record number, according to the Victory Institute. These candidates are running for seats at all levels of government — Congress, state legislatures, city councils and school boards, among others.

Herod said she thinks a number of candidates have been inspired to run because of the policies of President Donald Trump.

“This Trump administration is placing communities of color, marginalized communities, LGBT communities under attack every single day,” Herod alleged. “I’m very encouraged by what I’ve called a rainbow wave of queer people running for office across the country. It has been so inspiring to see that.”

It appears, however, that LGBTQ Republicans are retreating. Fewer hold office now than did eight months ago, and only about eight are running in the 2018 midterms, according to Gregory T. Angelo, president of the gay conservative Log Cabin Republicans.

Herod and Harrison lay the blame on the Trump administration. Unlike former Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, Trump has not recognized June as LGBTQ Pride Month since he has been in office, despite making overtures to the community during his 2016 campaign. He has also rescinded several Obama-era policies advancing LGBTQ rights, including trans bathroom protections for trans students, and he has tried to reinstate the ban on transgender people serving openly in the U.S. military.

Angelo sees the Trump administration in a different light, saying, “The notion that the LGBT community is under relentless attack by this administration is absolutely false on its face.”

Angelo pointed out that Trump recognized same-sex marriage during his 2016 presidential campaign, which Obama failed to do in 2008. Angelo also said Trump sent the Log Cabin Republicans a letter in 2017 commemorating the organization’s 40th anniversary, becoming the first sitting GOP president to formally and publicly recognize the group.

“If the greater LGBT community is truly looking for wins in the area of LGBT equality, they need to reckon with the fact that we live in a Republican country,” Angelo said.

“There’s a Republican president, Republicans control the United States Senate, Republicans control the majority of statehouses, Republicans control the majority of governorships, and so, any movement we have towards LGBT equality in the United States is going to need to come from LGBTs and from the Republican Party,” he added.

While LGBTQ Republican representation has declined over the past year, Angelo noted it has increased since he took the helm of Log Cabin Republicans five years ago.

Nonetheless, this year’s Republican state primaries will be an uphill battle for LGBTQ conservatives, Annise Parker predicted.

“State parties have tried to purge their ranks of anyone who is publicly pro-choice and anyone who is publicly pro-choice or is publicly LGBT,” Parker said. “It has to be a really good candidate with the right set of circumstances.”

Angelo disagreed and said “the data isn’t there” to back up Parker’s claims. “People can try to extrapolate their own conjecture, but that’s not the case,” he said.

One thing LGBTQ people on both sides of the political aisle can agree on is the need for more members of the community to hold public office.

“We have wonderful friends and allies and supporters who aren't members of the community,” Parker said, “and they can represent us well, but they can't be role models for our youth, and they can't advocate from the same position that someone who actually has the lived experience can.”

Holstege agreed, saying, “When I first was elected, someone tweeted me, ‘Now I have a bi politician to look up to.”

“If you don't see it, you don't know that you can get it,” Holstege added.