Introduction and summary

The gig economy refers to application-based technology platforms, or apps, that deploy armies of workers to perform services ranging from on-demand taxis and home cleaning and maintenance to meal delivery and child care. Some experts predict that this sector will transform the way Americans work and could offer workers unprecedented levels of freedom. Yet policies designed to keep workers safe and ensure that they receive decent wages may not apply to many workers in the gig economy. As a result, too many gig economy workers are stuck in unstable, low-wage jobs.

Gig economy workers are frequently classified as independent contractors—a status that by law means a worker is self-employed.1 Independent contractors may contract with multiple companies; are responsible for paying employer-side state and federal payroll taxes; and should receive significant freedom on how they provide services. Some argue that this freedom and flexibility is an incredibly important benefit for workers balancing multiple jobs and family commitments.

Yet, nothing in federal employment laws prevents companies from giving virtually the same measure of flexibility to their employees.2 Moreover, the independent contractor status leaves workers exposed to economic fluctuations as well as to abuse from contracting companies, because they are not covered under most workplace protection laws and do not receive workplace benefits.3

To shoulder these risks, independent contractors must have sufficient power to negotiate with their clients a pay rate higher than what would be paid to an employee to do similar work. However, many existing surveys suggest that independent contractors may be earning very low wages.4 Increasingly, large companies are driving down costs by shedding their role as an employer through a variety of means, including by relying on staffing agencies, franchises, and independent contractors to supply their workforce, according to Brandeis University’s David Weil.5

Nowhere is this happening more clearly than in the gig economy. By classifying workers as independent contractors, companies can save up to 30 percent on labor costs.6 This savings too often leads low-road companies to illegally misclassify their employees as independent contractors. Workers at several gig economy companies have filed lawsuits alleging that they are contractors in name only, arguing that their contracting companies do not provide sufficient independence to justify their classification as independent contractors and that they should be re-classified as employees.7

Yet even traditional employees are shouldering more risk. Retail and restaurant employees, for example, are increasingly subject to unpredictable, just-in-time scheduling that makes obtaining full-time work and planning for transportation and child care very difficult.8 Today, an estimated 40 percent of the American workforce is working for temporary staffing agencies, as independent contractors, or as part-time workers.9

Partly as a result of this fractured labor force, most working Americans no longer capture the full benefits of economic growth. Between the beginning of the economic recovery in 2009 and 2015, the top 1 percent of Americans received the majority of the gains in economic growth.10 The income of the top 1 percent grew by 37.4 percent during that time period, while the average income of the bottom 90 percent has grown just 4.6 percent.11 And while productivity has increased by about 72 percent since 1973, wages of the typical workers have remained essentially flat.12

Policymakers, gig economy companies, and worker advocates increasingly debate how to shape policy that will raise standards for independent contractors in the industry while maintaining the technological innovations that consumers enjoy. While the federal government is unlikely to act to improve conditions for gig economy workers in the near term, progressive state and local governments are beginning to adopt policies to provide benefits and a voice on the job for these workers.

Yet, in many communities, workers classified as independent contractors have few legal protections, and more can be done in even the most innovative cities and states. For example, while a number of communities are debating how to provide benefits to gig economy workers, without policies that ensure a baseline wage threshold or that grant workers a voice in determining their wages and benefits, low-road companies could respond to requirements to contribute to benefits with commensurate decreases in pay.

Specifically, cities and states can raise standards for independent contractors by:

- Creating a wage threshold for all independent contractors

- Creating platforms and protections to deliver needed benefits to workers

- Providing a pathway for workers, companies, and government to negotiate for industry-specific wages and benefits

These policies would ensure that high-road companies that provide decent jobs can thrive without being undercut by those who fail to meet minimum standards for their workers.

While this report does not specially address policies to combat employee misclassification, our recommendations will reduce the incentives for companies to illegally misclassify their employees by reducing the cost difference between independent contractor and employee status.

Moreover, we reject policies that either require workers to forfeit their employment rights under the laws in exchange for the provision of a limited set of benefits or that carve workers out from coverage entirely. Decisions on whether workers are misclassified should be determined by the courts, based on the specific facts of the case.

We hope this report will add to the ongoing conversation about how to address the needs of workers in the gig economy and serve as a compliment to existing proposals to ensure that workers are properly classified.13

Access to workplace protections and benefits

Independent contractors inside and outside of the gig economy do not receive a host of benefits and protections afforded to traditional employees. Many argue that workers are willing to forgo employment benefits, in part because they have greater opportunity for independence and flexibility. However, surveys of contractors show that they increasingly desire both flexible work arrangements and needed benefits.14 Moreover, research demonstrates that access to a strong social safety net is needed to allow these workers to start and maintain their own businesses.

Existing protections and benefits

Under U.S. employment law, independent contractors enjoy far fewer legal protections and are far less likely to receive company-provided benefits than workers classified as employees. Workers classified as employees receive minimum wage and overtime protections under the Fair Labor Standards Act; are allowed to form unions and collectively bargain under the National Labor Relations Act; are able to collect unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation in the event of a job loss or workplace injury; and in a number of states and cities, are entitled to paid sick leave and hourly wages higher than the mandatory federal minimum. Employees also split payroll tax contributions for Social Security and Medicare with their employers and are eligible to receive company-provided benefits such as contributions to retirement savings plans and paid family leave.

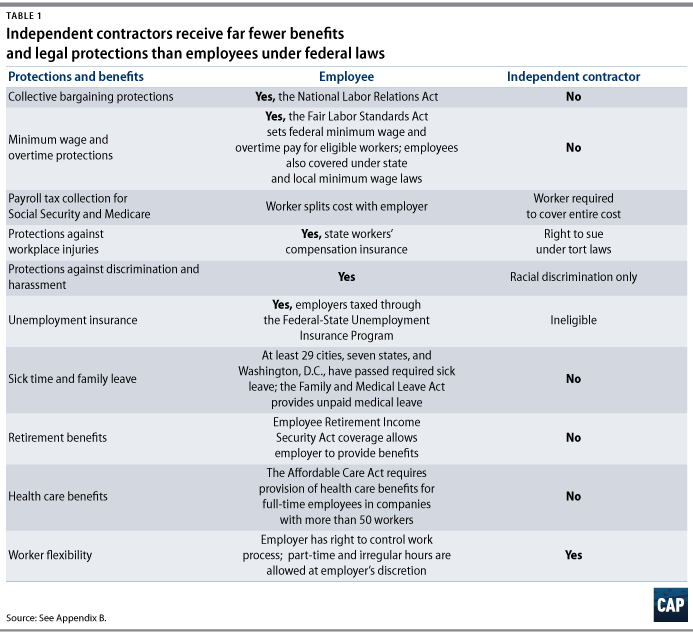

Independent contractors, on the other hand, receive few protections under U.S. employment laws. (see Table 1) Under federal law, contractors have no guaranteed minimum wage or overtime protections; have no protected rights to form unions or collectively negotiate for better wages and benefits; and do not receive unemployment insurance or workers’ compensation in the event of a job loss or workplace injury. And if contract workers lose a contract or are otherwise discriminated against on the basis of age, religion, sex, disability status, or national origin, they have little recourse.15 Moreover, discretionary company-provided benefits—such as paid leave and retirement contributions—are not typically available to independent contractors.

State and local workplace laws typically follow this pattern of providing protections for workers based on their employment status. Many cities and states have enacted laws requiring companies to pay wages higher than the federally mandated $7.25 per hour and to provide paid sick and family leave, but these laws apply only to employees.

A handful of innovative governments are starting to enact laws to ensure that independent contractors and other types of unprotected workers receive the pay and benefits that they deserve. Most recently, New York City enacted the Freelance Isn’t Free Act in order to impose penalties on companies that fail to pay their contractors and grants the city enforcement authority.16 And in order to protect contractors who are injured on the job, New York state established the Black Car Fund, which provides workers’ compensation for drivers who are independent contractors.17 A number of states have adopted statutory employee laws that require companies to pay into the workers’ compensation system to cover independent contractors in a certain limited number of job categories.18 Likewise, at least seven state legislatures have enacted a Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights to provide basic labor protections to caregiving workers who were carved out from receiving protection under federal workplace laws, despite being classified as employees.19 Finally, the Seattle City Council voted in 2015 to give taxi drivers, for-hire drivers, and transportation network company drivers the ability to unionize.20 Yet in even in the most innovative jurisdictions, contractors receive significantly fewer protections and benefits than employees.

In order to shoulder the additional risks and costs associated with their work status, contractors must be able to negotiate with companies for a pay sufficient to purchase health and disability insurance; save for retirement, periods of unemployment and underemployment, and illness; and cover any business costs and the full cost of Social Security and Medicare taxes.

When independent workers are not able to negotiate for this sort of a pay premium, companies relying on contracted labor rather than employees can enjoy significant cost savings. The average cost of legally required benefits for employees—including unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation, Social Security taxes, and Medicare—is about 11 percent of a worker’s pay.21 All totaled, when the cost of discretionary benefits such as health insurance, retirement contributions, and paid leave is added to legally required benefits, it accounts for about 30 percent of employees’ total compensation packages, on average.22

Companies hiring contractors can also enjoy significant cost savings in the event that a worker causes harm or injury to another person. While employers are liable for employees’ negligent acts or omissions in the course of employment, businesses that hire independent contractors are generally absolved from this liability.23

Flexibility and independence

Despite the lack of access to traditional benefits, many argue that the independent contractor classification can provide significant advantages to workers. With this status, they contend, comes the unique ability for companies to provide independence and flexibility—particularly flexible scheduling.24

Surveys show that all workers—and particularly Millennials and working parents—are increasingly looking for jobs with flexible scheduling.25 Indeed, available data indicate that workers participating in the gig economy do so, in part, because of its flexible work schedule. In a 2014 survey commissioned by the Freelancers Union and Elance-oDesk, 42 percent of freelancers reported that they chose contract work in order to “have flexibility in my schedule.”26 And an analysis of Uber’s driver data by economists Jonathan Hall and Alan Krueger found that there is significant variability in the number of hours that drivers work from week to week.27

Yet worker advocates point out that this flexibility is limited by industry rules and practices—for example, guidelines from transportation network companies indicate that workers must accept nearly all rides offered.28 And a 2017 article in The New York Times explored how gig economy companies influence when, where, and how many hours workers put in through the use of “psychological inducements and other techniques unearthed by social science.”29

Moreover, federal and state workplace laws do not prevent companies from allowing flexible scheduling for their W-2 employees. Indeed, legal scholars have made this point in order to argue that nothing prevents gig economy companies from reclassifying their workforce as employees and maintaining flexibility.30

And while some have claimed that gig economy companies must classify workers as independent contractors in order to offer a flexible schedule, the fact that a company does so is not generally sufficient evidence under the law to demonstrate that such workers are running their own businesses and should therefore remain classified as independent contractors.31 Under the Obama administration, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) issued an interpretation of the Fair Labor Standards Act that said that flexibility alone is not a significant factor in determining employee status.32

In practice, when gig economy companies have converted their independent contractor workforce to employees, they have also begun to exert more control over their workforce. Several gig economy service providers—such as Instacart, Shyp, and Hello Alfred—now use employees instead of independent contractors or, in some instances, use a mix of employees and independent contractors.33 While the law allows these companies to maintain the same level of flexibility and independence of their workforce, many have indicated that they will rein in some flexibility for employees.34

For example, Instacart—an app-based grocery delivery service—announced in June 2015 that it would start allowing its shoppers in some locations to choose to become part-time employees instead of independent contractors and later began hiring new shoppers as employees. As employees, workers are covered under workers’ compensation insurance and the company will pay for other employment-related taxes. While employees still could pick their own shifts, they now set their schedules in advance and are subject to maximum hours limits.35

Similarly, if cities and states require companies using independent contractors to abide by higher standards—and thereby increase the cost of contracting out labor—companies employing contractors may re-evaluate whether the labor savings associated with this status is worth allowing these workers flexibility and independence.

Independent contractors want flexibility and economic stability

While the conversion to employee status may be the preferred and statutorily required outcome for some workers, many properly classified independent contractors would like to receive benefits from their contracting company while maintaining this status.

More than half of freelancers say they began their current work arrangement out of choice, according to the 2014 Freelancers Union and Elance-oDesk survey, yet 21 percent of workers freelancing part time reported that availability of affordable benefits was a top barrier to freelancing more.36 A 2015 survey of gig economy workers commissioned by the Aspen Institute and TIME magazine found that although gig economy workers were about evenly split on whether they prefer the security and benefits of working for a traditional company—41 percent—or the independence/flexibility of the on-demand economy—43 percent—nearly three-quarters said they should be given more benefits as part of their job.37

Gig economy companies increasingly report an interest in providing access to these sorts of benefits—but say that they are hesitant to do so out of fear that such actions be considered in misclassification lawsuits. In 2015, several gig economy companies joined worker advocates and think tanks on a letter calling for safety net reforms to ensure that all workers, no matter how they are classified, have access to the benefits they need.38 And the Freelancers Union, a nonprofit organization that promotes the interests of independent contractors through advocacy and services, offers its members access to both health insurance and retirement plans.39

While it is possible for independent contractors to access benefits such as health care and retirement through a spouse, a third-party actor, or an individual plan, they are significantly less likely to have this sort of coverage as compared with workers in traditional employment programs. Only 13 percent of self-employed workers had access to a workplace retirement plan in 2011, a decrease from 18 percent in 1999.40 And despite the fact that the Affordable Care Act allows independent contractors to purchase insurance outside of an employment arrangement, 20 percent of unincorporated, self-employed workers reported that they did not have health insurance in 2016, as compared with only 10 percent of wage and salary workers.41

Yet, as collected in a 2015 article by Walter Frick for The Atlantic, numerous studies have demonstrated that access to a strong social safety net enables workers to start and maintain their own businesses.42 For example, a 2010 RAND Corporation study found that American men were more likely to start their own business after qualifying for Medicare at the age of 65 as compared with just before.43 And after France reformed its unemployment system to make it more generous, there was a significant increase in the entrepreneurship rate.44 Value added per worker two years into business was 7,000 euros higher after the unemployment insurance expansion.45

Likewise, Harvard Business School’s Gareth Olds compared entrepreneurship rates for households that just barely qualified for the government-funded State Children’s Health Insurance Program to households whose incomes were slightly more than the cutoff, finding that eligibility in the insurance program increased the self-employment rate by 23 percent and that the survival rate of new business increased by 8 percent.46 Similarly, McMaster University economist Philip DeCicca found that New Jersey’s adoption of a state health insurance plan for uninsured adults increased self-employment among New Jersey residents as compared with other states.47

Finally, government reviews have shown that programs to reduce the cost of health insurance for self-employed workers have led in increases in business survival rates. For example, economists at the U.S. Department of the Treasury found evidence suggesting that increasing the deductibility of health insurance premiums for self-employed individuals from 60 percent to 100 percent between 1999 and 2003 decreased the probability of exiting self-employment by nearly 3 percentage points.48

Despite the increasing demand and demonstrated benefits of a strong safety net for all workers, too many independent contractors lack access to benefits. Moreover, the next section demonstrates that many low-wage contractors may not be compensated for the lack of benefits through increased pay.

Is low-wage contracting work growing?

Independent contractors are part of a much larger subset of the workforce that includes workers who lack the security and stability of a regular, full-time job and are often paid lower wages. While academics debate the size of this workforce—referred to as the precarious workforce—many argue that the portion of workers employed in these types of positions is growing as companies seek to minimize the costs associated with pay, benefits, and regulatory compliance. Moreover, a number of surveys indicate that too many independent contractors are earning low wages.

Size and growth of the precarious workforce

The precarious workforce includes workers with insecure employment arrangements with few job protections, including temporary workers, freelance workers and independent contractors, part-time workers, and day laborers. The exact size and growth of this workforce is debated, but workers employed under precarious work conditions make up a significant portion of the larger workforce, with estimates that 4 out of every 10 workers are now employed in precarious situations.49 These workers typically face higher income volatility than workers in traditional employment relationships because they spend more time unemployed or underemployed and some have low earnings.50

The data on precarious workers are unclear, partly owing to difficulty in defining these workers and partly owing to the simple lack of data directed at understanding this workforce.51 While the DOL has historically collected the most detailed and direct source of government data on contingent workers and independent contractors, a subset of the broader precarious workforce, such a survey was last conducted in 2005.52

In the meantime, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report in 2015 finding that the proportion of the total U.S. workforce participating in alternative work arrangements increased from about 35 percent to 40 percent between 2006 and 2010, while the subcategory of independent contractors remained virtually unchanged.53

Researchers debate what has been happening in the intervening years, particularly with the rise of the gig economy. University of California, Berkeley, sociologist Annette Bernhardt conducted a review of the current data in 2014, finding that while there is an intuition about the rise of precarious employment resulting from the reorganization of work and production, it is not immediately evident in statistics about the labor force. Using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), she found that the percentage of the workforce defined as self-employed has remained relatively stable over time.54

However, based on even these conservative estimates from the CPS Annual Social and Economic Supplement, the portion of the U.S. workforce classified as independent contractors is significant—an estimated 6.2 percent of the American workforce, or nearly 10 million workers.55

Moreover, a number of academics and research organizations using other government data sources have found that there has been significant growth in the portion of U.S. workers classified as independent contractors. Economists Larry Katz and Alan Krueger found that the number of workers filing a 1099 form increased in the 2000s—from 2000 to 2012—even while the CPS statistics on self-employment have declined.56 Initial research from labor economists Katharine Abraham, John Haltiwanger, Kristin Sandusky, and James Spletzer similarly has found that more than 80 percent of workers represented as self-employed in Detailed Earnings Records data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) are not classified as self-employed in census data.57

Furthermore, looking prospectively, Intuit Inc. and Emergent Research released a forecast in 2015 predicting that the number of Americans working as providers in the gig economy would grow from 3.2 million to 7.6 million by 2020.58

New data on independent contractors and other workers in alternative work arrangements are forthcoming. The Contingent Worker Supplement to the CPS was conducted again in May 2017 and its results will include data on self-employed independent contractors.59

Existing evidence on the wages of independent contractors

Previous research on independent contractors and other types of precarious employment relationships has shown that these workers often earn significantly less than employees or better-resourced entrepreneurs.

While there is debate over the accuracy of self-reported income data of the self-employed, the data nonetheless show that there is a wide distribution of earnings among self-employed workers such as independent contractors, with low-income workers earning less than their wage and salary counterparts and high-income contractors earning more than their wage and salary counterparts.60 Indeed, occupations with high rates of workers classified as independent contractors include low-wage occupations—including landscapers, cab drivers, and caregivers—as well as occupations at the high end of the income spectrum—such as management consultants, lawyers, and architects.61

Looking particularly at low-income workers, one study using the Survey of Income and Program Participation found that low-skill self-employed workers fare worse than their wage and salary counterparts when controlling for education, age, wealth, workforce background, skills, and other characteristics associated with earnings levels.62 Likewise, a study looking at self-employed workers in the 1980s found that the self-employed earned less than their wage and salary counterparts when controlling for observable traits that are generally associated with skill level and ability, such as experience and education.63

Similarly, the GAO has estimated the earnings of contingent workers using a similar question as the one used by the Contingent Worker Supplement, finding that they earn less than half of what standard workers earn—$14,963 compared with $35,000 annually. And after controlling for factors such as full-time status, industry, and unionization rates, the GAO estimated that contingent workers still earn 89 percent of what standard workers earn.64

However, there is also deliberation over the accuracy of self-reported earnings of self-employed workers. Annette Bernhardt and Sarah Thompson examined job characteristics of independent contractors in California in a 2017 report.65 They noted the challenges of estimating earnings of independent contractors using survey data due to the propensity of self-employed people to underreport their business income. As such, they estimated the median earnings of Californian independent contractors as a range between $24,000 and $66,667, with the high end of the range based on an IRS estimate that total nonfarm proprietor income is underreported to the IRS by 64 percent.66

We analyze data from the CPS in the appendix to this report. Potential underreporting of self-employment income makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions on independent contractor earnings when compared with their peers, but the data clearly show a wide variance in earnings among independent contractors and lower wages for low-wage independent workers than low-wage employees even after adjustments for underreporting.

Finally, new work is emerging on the earnings of gig economy workers. In a paper published by Alan Krueger and Uber economist Jonathan Hall, aggregated data on driving histories, schedules, and earnings of drivers on the Uber platform in 2014 found median earnings ranging from $16.89 per hour for drivers who drove 15 hours a week to $18.31 for drivers who drove from 35 to 49 hours per week across major Uber city markets including New York City and Los Angeles.67 However, these numbers were gross earnings that did not account for driver expenses. A follow-up study by Buzzfeed—which used Uber data and incorporated estimated costs to drivers, such as car depreciation, fuel, insurance, and maintenance, with methodology that was reviewed by the company—found that after costs in 2015, drivers earned $13.17 per hour in Denver, $10.75 per hour in Houston, and $8.77 per hour in Detroit, just slightly above the Michigan state minimum wage.68 And a 2016 report from the Pew Research Center found that gig economy workers are nearly twice as likely to come from low-income households: 49 percent of gig economy workers reported that they earn less than $30,000 annually compared with 26 percent of all U.S. adults.69 Similarly, gig economy workers have reported very low earnings and high business costs in numerous press accounts and online surveys.70

Furthermore, a study by JPMorgan Chase looked specifically at gig economy workers working for labor platforms—such as ride-sharing companies—and capital platforms, like temporarily renting one’s apartment. It found that workers on labor platforms relied on their gig economy earnings either as a primary source of income or to make up for poor earnings from nonplatform work. One-quarter of those actively earning money from labor platforms heavily relied on this income, earning 75 percent of their total income for a given month from gig labor.71 Overall, those earning money from online labor platforms appeared to use it as a substitute for volatile nonplatform work during downturns at their other jobs. In months where individuals worked for a gig labor platform, they earned 15 percent of their income through gig work. However, in these months, they earned 14 percent less in nonplatform income, earning just 1 percent more on net. In contrast, earnings from capital platforms were not used to replace lost nonplatform income. Workers for capital platforms earned 7 percent more in months where they worked through a platform.

While this study demonstrates that workers are using platform work to meet their financial needs, one recent survey found that many independent contractors are not secure even with these earnings. The report “The 1099 Economy” by Requests for Startups found that the number one reason independent contractors left working a 1099 job contracting for on-demand companies was the pay. A full 43 percent listed insufficient pay as their reason for leaving. When asked whether they feel secure in their financial situation, 41 percent of on-demand workers said they disagreed or strongly disagreed.72

Finally, it is important to note the policy implications of these findings. Most of the debate around ways to support independent contractors focuses on policies to provide benefits rather than actions to raise wages for these workers. However, as discussed in the previous section, contract workers are not covered by wage protection laws and collective bargaining laws. As a result, low-road companies would have a strong incentive to respond to requirements to contribute to a contract workers’ benefits with commensurate decreases in pay. Without the creation of minimum standards for these workers, any provision of benefits threatens to come at the expense of earnings.

Are gig economy workers independent contractors, employees, or something else?

Most gig economy companies rely on a frontline workforce staffed by independent contractors. Workers at many of these companies have filed lawsuits and petitioned state agencies, claiming that they should be reclassified under existing employment laws. They argue that their companies behave like employers—determining, for example, what workers wear, what they say to clients, and how to complete their job.73

A number of government officials have found in favor of workers. Both the New York State Department of Labor and the California Labor Commission and Unemployment Insurance Appeals Board have found that some former Uber drivers were employees and therefore due unemployment insurance.74 And Oregon’s Bureau of Labor and Industries Commissioner issued an advisory opinion finding that Uber drivers are employees based on a number of factors, including the degree of economic dependence of workers, Uber’s level of control, and the fact that their work is an integral part of the business.75ny such case would be decided on the specific facts and legal arguments presented.” Uber executive William Barnes contested Commissioner Avakian’s findings, arguing that it was “on an erroneous and incomplete picture of how drivers use the Uber application in Oregon and as such, is filled with factual errors and assertions that are simply wrong.”] Under the Obama administration, the DOL issued guidance on misclassification. While the guidance was not specific to the gig economy, it concluded that “most workers are employees under the [Fair Labor Standards Act].”76

In addition, there are several major cases moving through the courts. For example, Uber is facing a misclassification suit by workers in California and Massachusetts. After a federal judge rejected a $100 million settlement in 2016, finding that “the court cannot find that this settlement is fair and adequate,” Uber appealed the court’s decision to allow about 300,000 workers to join the suit.77 At the time of publication, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals was reviewing the appeal. 78 Another class-action lawsuit involving ride-share operator Lyft settled last year with workers receiving payments and some additional protections while allowing drivers to continue to be classified as independent contractors.79

Uber and Lyft have maintained that their drivers are not employees in cases before the courts and regulatory bodies.

Rather than letting these cases proceed, state policymakers are increasingly adopting legislation that would carve gig economy workers out from workplace protections. According to a recent report from the National Employment Law Project, 23 states have created employment tests that apply only to transportation network companies, exempting them from minimum wage requirements or employer-side contributions to workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance.80 And policymakers in New York state circulated draft legislation this past session that would provide workers with a modest benefits contribution—2.5 percent of the cost of each transaction—in exchange for covered workers forfeiting their claim to be reclassified as employees.81 Other advocates argue for the creation of a new, intermediate classification for gig economy workers that would maintain the flexibility associated with an independent contractor classification while allowing the platforms to provide some essential benefits.82

Yet these solutions generally ignore the variability of business models across the gig economy.83 Some platform companies function simply as an online market that brings together consumers and independent providers who have significant autonomy—with workers, for example, setting their own prices, and guaranteeing their own qualifications. Other gig economy companies create a branded identity across the platform, controlling, for example, pricing, worker uniforms, and qualifications and service quality.

The DOL’s former head of wage enforcement, David Weil, recently suggested that weighing whether gig economy workers should be classified as employees or independent contractors is not so different than making the same determination for workers at brick-and-mortar businesses.84 Existing legal tests to determine whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor are multifactor, fact-based exercises based on the level of control a company exerts over the workers in question. The fact that a company offers flexibility is not generally sufficient evidence under the law to demonstrate that workers are running their own business.85

Moreover, any new test for a third work status would likely overlap with these existing tests and would probably create more confusion and litigation.86 And while new benefits provided through these laws may represent an immediate gain for gig economy workers, they are often far fewer than what these workers would receive if they were reclassified as employees.

In the countries that have adopted intermediate classifications, the evidence on the effectiveness of these laws is mixed. For example, in Canada, courts have ruled in favor of so-called dependent contractors that accused companies of violating their notice of termination rights.87 However, these workers have achieved only limited success in exercising their collective bargaining rights.88 And in Sweden, where some contractors are covered by collective bargaining and health and safety laws, some legal scholars argue that the relevant law is now obsolete as the county increasingly classifies these types of workers as employees.89

Instead of exempting gig economy workers wholesale from workplace protections or requiring workers to forfeit their rights in exchange for benefits, cities and states can adopt policies to ensure that benefits provision is not evaluated as part of an employment test while still allowing workers to pursue misclassification claims based on other factors. Indeed, this is the approach of the Black Car Fund in New York state and new legislation in Washington state to establish a portable benefits fund for gig economy workers.90

Ultimately, whether a gig economy company is misclassifying its workforce should be determined through the judicial process, based on the particular facts of a case. By raising standards for all independent contractors, policymakers will help reduce the incentive for low-road companies to misclassify their workers in the first place.

Policy recommendations

The growing gig sector is shining a spotlight on problems that independent contractors across industries face: Although flexibility is an essential benefit for these workers, all too often flexibility does not make up for poor pay, few benefits, and the lack real power to negotiate for better workplace conditions.

While meaningful action to raise standards for gig economy workers at the federal level is unlikely in the near term, state and local policymakers have significant power to raise standards for these workers. However, there is significant debate about how to best raise standards and support innovation.

Policy recommendations range from ideas that would provide a limited set of benefits to gig economy workers to plans that would essentially ensure that independent contractors are afforded the same rights and benefits as employees.91 State and local governments have significant freedom to innovate, because independent contractors are exempt from most federal workplace protection laws. Indeed, as discussed above, a number of communities have adopted policies to ensure that contractors are paid the wages they are owed, can collect necessary benefits, and have a voice on the job.

As we crafted policy in this space, we talked to worker advocates, innovative businesses, and legal experts with the goal of raising wages and standards for independent contractors broadly, providing these workers universally needed benefits as well as a say in obtaining nontraditional benefits, and ensuring that the system would be practicable for participating companies.

Specifically, we recommend that state and local governments:

- Create a wage threshold for independent contractors

- Create platforms and protections to deliver needed benefits to workers

- Provide a pathway for workers, companies, and government to negotiate for industry-specific wages and benefits

We intend for these policies to apply to independent contractors with no employees, who rely on their own labor—rather than capital investments—for income.92

Create a wage threshold

Because independent contractors enjoy few protections and benefits under existing employment laws, they must be able to obtain pay sufficient to purchase health and disability insurance; save for retirement, periods of unemployment and underemployment, and illness; and cover day-to-day expenses as well as their additional tax burden. Yet there are no protections to ensure that independent contractors are being paid even the minimum wage.

Companies should be required to certify that they pay at least 111 percent of the state or local minimum wage to any worker classified as an independent contractor with no employees of their own. This proposed threshold is calculated by adding to the minimum wage the average cost of employer-provided legally required benefits—which is about 11 percent of pay, according the Bureau of Labor Statistics.93 The average cost of employer-provided mandatory benefits includes the employer’s share of Social Security and Medicare taxes, state and federal unemployment insurance taxes, and workers’ compensation insurance. In order to ensure compliance, governments could also adopt reporting and disclosure requirements.

This threshold is quite conservative. It does not include a premium for forgone employee benefits or business expenses, such as provision of supplies and transportation costs between jobs. Indeed, if policymakers were to establish an industry-specific contractor wage threshold, they may want to account for these sorts of costs. The wage threshold could rise in tandem with any increases to the state or local minimum wage or inflation.

Currently, this would be equal to $8.05 per hour in cities and states without a minimum wage set higher than the federal level. In locations with a $15 minimum wage, for example, the contractor wage threshold would be $16.65.

By setting such a threshold, policymakers would help prevent low-road companies from using the independent contractor classification to pay less than what they are legally required to provide to even the lowest-paid employees, and thereby unfairly compete against companies that pay living wages. Moreover, it will help protect workers against the additional risks associated with an independent contractor status and ensure that any provision of benefits don’t come at the expense of wages.

Setting higher wage thresholds for workers exposed to additional risk is not without precedent. Australia requires companies to pay higher wages to workers with irregular hours and no employment guarantee—often set around 25 percent higher than minimums for traditional employees.94 Similarly, the United Kingdom has extended minimum protections to all contracts where an individual agrees to personally carry out work without running a genuine business, and worker advocates in the country are pushing for gig economy workers to be covered by minimum wage protections.95

Adopting this change would require companies and workers to calculate whether their payments will meet the hourly threshold in a written contract.96 Independent contractors currently may charge for their work in a number of ways, including as a fixed amount for an entire project, as an hourly fee, or as a commission.97 In order to calculate whether fixed amount price contracts meet wage threshold requirements, this change would simply require a contract to include an estimate of the number of hours a contractor anticipates needing to complete the work along with existing information on total payment for the work. Because independent contractors are able to set their own hours, they would not be subject to overtime requirements.

This calculation is not without precedent when looking at wage and salary workers who have irregular shift rates. For example, employers are required to pay tipped employees at least $2.13 per hour under federal minimum wage requirements. However, if the employee doesn’t earn enough in tips to reach the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour, the employer must make up the difference.98 Similarly, the employers of workers who are paid on commission or paid a piece rate, day rate, or project rate are also liable to make up the difference if the worker’s earnings are under the federal minimum wage.99

In the case of gig economy companies, these calculations may be slightly more complex, but access to real time work data should allow for extremely accurate calculations of when a contractor is working. For example, in the case of ride-sharing companies, the application that connects riders to drivers also collects detailed data on when a driver logs on to its system, agrees to pick up a rider, and drops off the rider at a destination. With this level of data, the contracting company would be able to calculate total hours worked and rate of pay after the deduction of commission.

Some researchers argue that it is impossible to determine when a contractor is truly working for a company during the times when the worker is waiting to pick up a ride, because the driver could be using two applications at once or attending to personal business.100 However, as noted in a 2016 report by the Economic Policy Institute, both Uber and Lyft already have guaranteed pay plans that they use in some markets during certain hours that pay workers guaranteed minimum earnings per hour based on their entire time logged into the system, including waiting times.101

Indeed, whether a company would be required to pay workers for their waiting time prior to accepting a ride or another task should be determined based on the degree of control the company exerts over workers’ waiting time.102 Guidance for gig economy companies could be promulgated during a rule-making process or could be specifically addressed through a wage and benefits board structure. (see recommendations)

Finally, as communities adopt these changes, they should also consider the oversight and enforcement capacity of their government agencies. Cities and states can improve their ability to enforce these laws by partnering with community and worker organizations and allowing workers to go to court to enforce labor laws. San Francisco and Seattle have implemented programs that provide grants to community organizations that help enforce workplace standards and New York City’s Freelance Isn’t Free Act increases penalties on companies that are found to have shortchanged their workers.103

Provide workers with needed benefits

While a wage threshold would help ensure that low-road companies cannot use the independent contractor classification to pay poverty wages, independent contractors also need access to benefits that allow them economic stability during times of illness, injury, and job loss, as well as the ability to save for a secure retirement.

Executives of gig economy companies increasingly report interest in supplying benefits to their workforce, yet say they are reluctant to do so out of fear of misclassification lawsuits.104 Currently, in determining whether a worker is properly classified under employment laws, courts will generally evaluate a company’s level of control over that worker through economic dependence and common law tests.105 These varying tests look at numerous factors and sometimes specifically include whether the company in question provides benefits to its independent contractors.106

Companies should be encouraged to provide good benefits to their workers. Indeed, as long as a state or local policy requires company contributions to independent contractor benefits, these contributions should not be factored into employment tests. However, these policies should be narrowly written so that workers are not prevented from pursuing misclassification claims based on other factors.

At the same time, policymakers should focus on reforms that allow benefits delivery to happen through the government or at the industry level, because company-administered benefits would be practical only to a limited number of independent contractors who work for few clients. Indeed, independent contractors often provide services to multiple companies on jobs that can often last for just a few weeks or months. Moreover, these workers may be piecing together their contracting work with additional part-time or full-time jobs.

Policymakers can make such reforms either by expanding existing safety net programs to include independent contractors or creating new portable benefits programs that specifically target gig economy companies.

Expansion of government safety net programs

Most safety net programs are currently administered at the state or federal level, rather than the local level—meaning that states have a greater capacity to cover independent contractors through government safety net programs. In some cases, states should expand coverage of existing programs to include independent contractors, as is the case with workers’ compensation and state retirement systems. However, we recommend the creation of a new benefits fund within state unemployment systems to serve the needs of independent contractors when they are either unemployed or underemployed.

Specifically, state policymakers can take action to ensure that contractors have access to the following benefits.

Retirement

Only 13 percent of self-employed workers had access to a workplace retirement plan in 2011, representing a decrease from 18 percent in 1999.107 And although independent contractors are currently able to open their own individual retirement accounts, the law does not allow companies to make contributions to these plans.

Many states are considering legislation or taking steps to create low-fee, tax-advantaged public retirement savings systems for workers without access to an employer-sponsored plan.108 Independent contractors, along with other workers who do not receive a retirement savings account through their employer, should be included in these new systems and be permitted to sign up for the plan online and set up automatic direct deposit. These plans generally do not allow companies to make contributions to independent contractors’ retirement accounts, as is currently the case with employees. However, states should explore options in order to allow them to do so.109

Injury

Independent contractors in occupations with high injury rates, such as transportation network and delivery drivers, face unique challenges accessing affordable disability insurance. While our proposed wage threshold for independent contractors would ensure that companies are not paying less than what they are legally required to provide to employees, workers in occupations with high injury rates would still struggle to find affordable individual policies in the private market. Indeed, workers’ compensation—which is administered at the state level—is affordable due to the ability to pool risk across workers.

Independent contractors can access these benefits through statutory employee laws, which require companies to pay into the workers’ compensation system to cover independent contractors in a limited number of job categories. A number of states already cover contractors in certain occupations under these laws.110 State governments should identify occupations with high injury rates where a significant portion of the workforce is classified as an independent contractor and define these workers as statutory employees for purposes of workers’ compensation benefits.

Unemployment

Last year, the Center for American Progress, along with the National Employment Law Project and the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, released a plan proposing that the federal government create and fund a Jobseeker’s Allowance—a small, short-term weekly allowance to support work search, available to independent contractors, new entrants to the labor market, and other workers who would otherwise be ineligible for unemployment insurance.111 The proposed Jobseeker’s Allowance would offer a stipend of about $170 per week to jobseekers for up to 13 weeks to help these workers actively search for work and improve their employment-related knowledge and skills when employed or underemployed.

Such a weekly benefit would be quite modest relative to unemployment insurance, but it would serve as a government-funded support in addition to the pay supplement included in the contractor wage threshold. This would ensure that contractors would be provided modest income security during periods of temporary earnings loss.112

While it is unlikely that the federal government will take action to provide independent contractors with unemployment benefits under the current administration, states could pursue this program for all contractors or pilot it for smaller subsets of these workers.

These three programs to provide retirement, disability, and unemployment insurance represent essential steps that states may take to ensure that independent contractors receive the benefits they need.

Portable benefits funds

At both the state and local level, policymakers should consider how portable benefits funds could be used to raise standards for independent contractors at the industry level. These policies generally require companies to pay into worker benefits accounts managed by independent organizations. Moreover, worker advocates increasingly believe that these sorts of funds could be used to not only supply benefits but also give workers a stronger voice in advocating for the benefits they need.

Most proposals to establish portable benefits for workers are focused only on a single benefit. For example, New York state established the Black Car Fund in 1999. The nonprofit fund provides workers’ compensation for independent contractor drivers, funded through a 2.5 percent rider surcharge.113 While black car drivers are legally classified as independent contractors, the enabling legislation does not require them to be defined as such in order to participate in the benefit.

And in the state of Washington, progressive lawmakers introduced H.B. 2109 last session, which would create a portable benefits fund of the scale necessary to provide meaningful benefits to workers, including health insurance, paid time off, retirement savings, and workers’ compensation insurance.114 Modeled after a proposal by venture capitalist Nick Hanauer and Service Employees International Union Local 775 President David Rolf, the bill requires gig economy companies hiring independent contractors to contribute the lesser of 25 percent of the fee charged to consumers or $6.00 per every hour that the worker provides services to the consumer into portable benefits accounts.

Moreover, the legislation requires that independent, nonprofit organizations administer the funds and that at least half of a benefit provider’s board of directors be comprised of workers or their representatives. Also, these boards would have a fiduciary duty to make decisions in the best interest of workers. In this way, the bill would ensure that contracting companies would not have to shoulder the fiduciary responsibilities associated with benefits provision; eliminate any potential conflicts of interest; ensure that benefits contributions for the growing number of gig economy workers who work across multiple platforms could be consolidated in one account; and grant workers a voice in determining their own benefits.

Also, the bill would insulate companies from claims of misclassification based solely on benefits provision within the portable benefits system. At the same time, H.B. 2109 is narrowly written so that workers are not prevented from pursuing claims based on other factors. This would allow the courts to decide whether a specific company is misclassifying its workforce based on the particular facts of a case. Rep. Monica Stonier (D) will reintroduce the bill when the Washington State Legislature reconvenes for the 2018 session.

Finally, we again note that as lawmakers establish these sorts of benefits requirements, they should include minimum wage requirements. Without such protections, any contributions requirement could come at the expense of workers’ current earnings.

Allow companies and workers to work together to negotiate needed benefits

Too often, independent contractors have little power to negotiate with their clients over pay and benefits. While contractors with specialized skills may be able to negotiate with a company individually in order to obtain good pay and benefits, lower-skilled contractors have little power to negotiate on their own and are not covered under the federal labor laws that allow employees to come together in unions. Moreover, independent contractors face unique barriers that inhibit them from collaborating with their co-workers because they typically lack a shared work site where they would develop relationships with colleagues and surface mutual concerns.

In order to ensure that gig economy workers have a voice on the job and are able to negotiate for better wages and benefits, state and local policymakers should create wage and benefits boards for industries or occupations that rely heavily on independent contractors. These boards would bring together representatives of workers, businesses, and government to set minimum standards for industries and occupations.

As David Madland and Alex Rowell recommend in the recent CAP report “How State and Local Governments Can Strengthen Worker Power and Raise Wages,” the bodies would make their decisions on wage and benefit standards based on economic and social factors such as productivity and the skill level of the work as well as fairness and regional cost of living.115 Along with base wage determinations, board decisions could also include standards for benefits, training, leave, and pay differentials for additional skills or experience.

New York, California, and New Jersey have developed similar boards to determine the wages of employees in specific industries.116 For example, in New York, the governor has had the authority to convene industry-specific wage boards to “consider the amount to provide adequate maintenance and to protect health and … the wages paid” since the Great Depression era.117 In collaboration with the state’s commissioner of labor, a tripartite wage board with members from business, labor, and the community has been empaneled more than 30 times, most recently to raise the wages of fast food workers to $15 per hour.118

There are a number of measures that states can take to ensure that these boards are representative of the needs of workers and business owners in the industry. Workers, labor organizations, firms, and employer associations should be permitted to testify at hearings called by the bodies. Likewise, workers could be given the opportunity to empanel the board through petition and vote on the board’s final recommendations. For example, New Jersey’s law requires a wage board to be empaneled at the petition of 50 or more covered workers.119

The work of these boards could complement the minimum wage and benefits policies above. For example, industry- or occupation-specific wage standards could be higher than the floor set by across-the-board minimums in order to account for worker skill levels or business costs.

Moreover, these boards could provide important guidance on how to calculate legally required wages and benefits contributions at gig economy companies and help ensure consistent pay practices despite rapid change in the industry. This would help to prevent problems like Uber’s recent announcement that it owed its New York City drivers $900 each, on average, after improperly calculating the company’s share of passenger fees.120

While direct bargaining between independent contractors and companies may raise antitrust law issues, the tripartite structure of such panels—with the government functioning as the regulatory authority—provides a sound basis for the policy to resist any legal challenges. City and local policymakers, however, may need to ensure that they have the delegated authority to regulate the industry or occupations in question.

Because independent contractors are not covered under the National Labor Relations Act—which regulates bargaining for employees—state and local governments have considerable room to innovate and are increasingly experimenting with ways to provide a collective voice for these workers. Most recently, the Seattle City Council voted to give taxi, for-hire, and ride-sharing drivers classified as independent contractors the ability to unionize.121

In another example, California’s Agricultural Labor Relations Board requires mandatory mediation for collective bargaining agreements for agricultural workers.122 And lawmakers in Texas, Washington state, Alaska, and New Jersey have passed laws that allow doctors who are independent contractors to join together and collectively negotiate contracts with HMOs.123

Conclusion

Policymakers, gig economy companies, and worker advocates are increasingly in conversation about how to provide gig economy workers with the security and opportunity they need in order to succeed in the U.S. economy.

Our proposed reforms—establishing a wage threshold for independent contractors; creating benefits platforms and allowing company contributions to benefits that are universally needed; and allowing workers a collective voice in negotiating—achieve two important goals.

First, the proposed reforms answer many questions about how to design a system that is both supportive of workers and practicable for contracting companies: By rejecting an intermediate employment classification and creating wage standards, our proposal would raise standards for independent contractors broadly. Moreover, by allowing the government or nonprofit, worker-led organizations to play a role in the administration of benefits, the reforms are practicable for contractors working across industries and participating companies that can contribute to worker benefits on a prorated basis. Finally, by granting workers a mechanism for raising industry-specific wage and benefit standards, the reforms not only offer access to benefits that are universally needed today, but also create a mechanism for workers and businesses to jointly determine benefits needed in the future.

Second, by creating wage thresholds for independent contractors and ensuring that they are able to access needed benefits, policymakers can start to rebuild the link between wages and productivity for middle-income workers throughout the economy and ensure that the future gains of the country’s economic growth are more widely shared.

We hope that our recommendations help to move this conversation forward in ways that raise standards for all independent contractors, provide emerging companies with the freedom to innovate, and ensure that companies that respect their workers can compete on an even playing field.

About the authors

Karla Walter is the director of employment policy at the Center for American Progress. Walter focuses primarily on improving the economic security of American workers by increasing workers’ wages and benefits, promoting workplace protections, and advancing workers’ rights at work. Prior to joining the Center, Walter worked at Good Jobs First, providing support to officials, policy research organizations, and grassroots advocacy groups striving to make state and local economic development subsidies more accountable and effective. Previously, she worked as a legislative aide for Wisconsin State Rep. Jennifer Shilling (D). Walter earned a master’s degree in urban planning and policy from the University of Illinois at Chicago and received her bachelor’s degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Kate Bahn is an economist at the Center. Her work has focused on labor markets, entrepreneurship, the role of gender in the economy, and inequality. In addition to her work on the Economic Policy team, Bahn has written about gender and economics for a variety of publications, including The Nation, The Guardian, Salon, and The Chronicle of Higher Education. She also serves as the executive vice president and secretary for the International Association for Feminist Economics and as moderator of the organization’s blog, “Feminist Economics Posts.” Bahn received both her doctorate and master of science in economics from The New School for Social Research, where she also worked as a researcher for the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis.

For the Appendix figures of this report, see the PDF.

Appendix A: Survey data on the wages of independent contractors

To better understand the relative earnings of independent contractors compared with other workers, we used the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the Current Population Survey (CPS) to analyze the income and hours worked by employment classification. Academics debate the accuracy of self-reported income data among self-employed workers; in recognition of this, we adjusted the data to account for potential underreporting of income, as outlined below.

Potential underreporting of self-employment income in survey data makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions on independent contractor earnings compared with their peers. But the data clearly show a wide variance in earnings among independent contractors, and lower wages for low-wage independent contractors than low-wage employees even after adjustments for underreporting.

We analyzed the ASEC because it contains the most variables of interest, including figures on self-employed workers’ usual hours of work per week last year and estimated number of weeks worked last year in addition to the relevant earnings variables. This allows us to calculate an imputed hourly wage for these workers. Other surveys, such as the Outgoing Rotation Group, exclude self-employed earnings from earnings and hours variables, so it is not possible to calculate an hourly wage from these other surveys. Other data sets that are used in studies of entrepreneurs, such as the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, report on income earned from unincorporated businesses but do not classify workers along these standards as in the ASEC. The ASEC also provides the most current data available containing information on self-employed workers because it is published within the year it is collected, with 2016 data referring to earnings and amount of work in 2015 available for this report.

Defining independent contractors

Three classes of workers are defined by the CPS in its worker classification question, which refers to the person’s employer. These three classes are wage and salary workers, or employees; unincorporated self-employed workers; and incorporated self-employed workers. We assume that unincorporated self-employed workers are independent contractors whereas incorporated self-employed workers are business owners and entrepreneurs.

Calculating total earned income by worker classification

We calculated total earned income for all worker classifications as the sum of wage income, business income, and farm income from the CPS. Negative incomes were excluded. It’s necessary to include all three income categories because the data on earnings of unincorporated self-employed workers are collected as business income whereas the earnings of incorporated self-employed workers and wage and salary workers are tabulated as wage income. Farm income is included because a large share of agricultural employment is self-employment.124

Hourly wages were calculated by dividing annual pre-tax income by the usual weeks worked per year and hours worked per week in the previous year.125 Data show that independent contractors report lower imputed hourly earnings than their peers in traditional employment relationships and in incorporated businesses.

Moreover, independent contractors have lower annual earnings because they tend to work fewer hours per week and fewer weeks per year than their wage and salary counterparts. Independent contractors worked an average of 36.9 hours per week whereas employees worked an average of 38.9 hours per week. Independent contractors also work fewer weeks per year at a reported average of 45.7 compared with 47.1 for employees. While these differences seem small, they add up to a little more than 145 hours per year, or more than three weeks of wages. This resulted in independent contractors having self-reported median annual earnings of $25,000 compared with employees’ median annual earnings of $35,000 in 2015. Independent contractors at the 10th percentile in their respective worker classification self-reported earnings as low as $4.44 per hour, 57 percent of the earnings reported by employees at the 10th percentile (see Table A1).

Moreover, business income can be very low because it is calculated as gross receipts subtracting expenses. It can be reported in the negative, although negative values were excluded from our analysis. However, this means that those very close to having negative business income are included. It could have been a bad year for business. If it were possible to link across different waves of the CPS for these workers, then we could pool business income across years to get a better sense of a self-employed worker’s typical income, but unfortunately they are excluded from the relevant variables in the linked data in the CPS so it’s not possible to pool their earnings across years.

Adjusting for earnings underreporting

As noted above, research has found that the earnings data of self-employed workers are affected by underreporting. Self-employed workers may underreport their earnings in surveys due to the difficulty in calculating their incomes—as they may be working multiple jobs and receive payment in a piecemeal fashion—or due to financial incentives. Because self-employed workers pay full payroll taxes themselves, they have a stronger incentive to underreport their earnings to tax authorities than wage and salary workers.

The IRS estimates underreporting of earnings by nonfarm sole proprietorships using a sample of audits as well as additional imputations to account for income not found through audits. The latest data from the IRS show that in tax years 2008–2010, total nonfarm proprietor income was underreported by 64 percent.126 Nonfarm sole proprietorships are unincorporated, but may include both workers who are exclusively self-employed and wage and salary workers who earn additional pay through outside contracting. In 2014, approximately 24.6 million tax returns showed nonfarm sole proprietorship income—compared with 9.5 million individuals who reported being “unincorporated, self-employed” in the CPS.127

The method employed by the IRS used to estimate the total amount of underreported income of all nonfarm sole proprietorships, or gross tax gap, rather than the average amount of underreporting of households led by unincorporated self-employed individuals. The latest data from the IRS show that “items subject to little or no information reporting” have the highest levels of underreporting on tax returns.128

There is evidence that this underreporting is skewed toward a smaller portion of sole proprietors. Analyzing IRS National Research Program data from 2001, the GAO found that “understated taxes are spread unevenly among the population of sole proprietors, and slightly more than 1 million sole proprietors accounted for most of the understatements.”129

Numerous studies have reviewed whether this underreporting extends to household survey data. Unlike when filing their taxes, self-employed workers have no financial incentive to underreport their earnings on household surveys. However, they may simply report the same number they used on their tax return.

This research relies on a methodology that assumes that households at similar earnings levels will have similar levels of consumption, and then estimates the degree of underreporting by self-employed workers by comparing their household consumption levels to those of employees.

A paper by economics professor Dmitriy Krichevskiy argues that entrepreneurs underreport their earnings, as evidenced by their greater consumption compared with employees.130 A study by economists Erik Hurst, Geng Li, and Benjamin Pugsly used data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey on total household expenditures as well as spending on food and nondurable goods to estimate the degree to which self-employed workers are underreporting their total family income on U.S. surveys. While the study used household data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, whereas our estimates are based on individual earnings from the CPS, the authors concluded that self-employed workers, not delineated by incorporation status, may be underreporting their labor earnings plus business income by 27 to 38 percent.131 Another study by economics professors Thomas Åstebro and Jing Chen used the same methods and data as Hurst, Li, and Pugsley, but relaxed the assumption of homogenous expenditure preferences and refined the model assumptions to look only at expenditures for food at home to find that underreporting for self-employed workers ranged from 18 to 27 percent.132 Åstebro and Chen reviewed additional literature and stated that adjusting for underreporting generally raises earnings of self-employed workers by 10 percent to 40 percent and that this range may vary based on the characteristics of the self-employed worker.133

Because we were relying on comparative individual earnings levels based on household surveys, we focused on estimations of the degree of underreporting based on consumption methodology.

We adjusted our earnings calculations to account for this underreporting by accounting for a range of 20 percent to 40 percent underreporting. Even if we accept the high estimation of a 40 percent underreporting rate, low-income independent contractors are earning such a significant amount less than low-income employees that they would still earn less than wage and salary workers even after accounting for underreporting. And wage and salary employees are required to receive employer-side contributions to Social Security and Medicare as well as unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation coverage, which on average results in a 11.2 percent additional payment on top of wages for employees. Table A1 shows that the lowest-wage independent contractors earn 26 percent less when accounting for 30 percent underreporting and employees’ legally required benefits of 11.2 percent of earnings, and earn 13.5 percent less when accounting for 40 percent underreporting.

Assuming an underreporting rate of 30 percent, independent contractors at the 10th percentile are earning less than minimum wage at $6.34 per hour. At an underreporting rate of 40 percent, independent contractors at the 10th percentile are earning just $7.40 per hour.

Finally, assuming 40 percent underreporting, we found that 9.4 percent of independent contractors earn less per hour than employees earning the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour, and nearly 1 in 4 earn less than $15 per hour.

Other factors that could influence the earnings of independent contractors

The results of this analysis could be influenced by a number of other factors, including total hours of work, workers’ willingness to trade lower earnings for greater flexibility, and employee misclassification. While we decided not to adjust the above calculations for any of these concerns, we briefly discuss each issue below.

Independent contractors may be incorrectly reporting their total weeks worked and hours worked per week. In 2016, most workers reported that they worked 52 weeks in the last year, with 69 percent of unincorporated self-employed workers reporting 52 weeks, 84 percent of incorporated self-employed workers reporting 52 weeks, and 77 percent of wage and salary workers reporting 52 weeks. The incidence of reporting 52 weeks of work per year is common across all classifications of worker, but is less common for unincorporated self-employed workers, so there is no reason to believe it would bias these workers’ implied wages downward due to overestimating weeks worked per year among unincorporated self-employed workers.

Some researchers have found that workers who work long hours—50 hours or more per week—tend to exaggerate the hours per week that they spend at work, while workers who work few hours tend to underreport the hours per week that they spend at work, although this finding is based on reported hours worked in the last week and has been contested.134 Our data use self-reported estimates for hours worked in the last year, which are less widely dispersed than data on hours worked in the previous week.135 Regardless, because unincorporated self-employed workers on average report lower average hours of work per week, as with weeks worked per year, there is no reason to believe it downward-biases these workers’ implied wages.

Some observers of the gig economy may argue that the wage differential observed between unincorporated self-employed workers and employees is, in part, voluntary. That is, contractors willingly exchange lower wages and fewer benefits in order to obtain a job with greater flexibility.136

However, research does not generally support the theory that workers must forgo higher wages in order to obtain more workplace flexibility. One study by economist Elaine McCrate found that any reduction in wages associated with the benefit of flexibility is modest at best and, in fact, many jobs with greater flexibility have higher wages.137 Furthermore, the volatility of earnings for many independent contractors would offset any compensating wage differentials, because workers cannot compare the value of flexibility to higher earnings when they aren’t able to predict their earnings as independent contractors.138

Finally, we should note that independent contractor misclassification may affect the data. It is estimated that 10 percent to 20 percent of employers misclassify at least one worker as a contractor and give these workers a 1099 tax form even though they should be employees receiving a W-2 form.139 However, these workers may identify as employees when surveyed by the Bureau of the Census for the CPS.

Appendix B: Table 1 sources

For more on collective bargaining protections, see National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S. Code § 151–169; National Labor Relations Board, “Rights We Protect,” available at https://www.nlrb.gov/rights-we-protect (last accessed September 2017); On Petition for Review and Cross-Application for Enforcement of an Order of the National Labor Relations Board, FedEx Home Delivery, Petitioner v. National Labor Relations Board, Respondent, U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (April 21, 2009) (No. 07-1391), available at https://www.cadc.uscourts.gov/internet/opinions.nsf/F52CAE60981DFB028525780000761CC4/$file/07-1391-1176680.pdf.

For more on minimum wage and overtime protections, see Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, 29 U.S. Code § 201; U.S. Department of Labor, “Wages and Hours Worked: Minimum Wage and Overtime Pay,” available at http://www.dol.gov/compliance/guide/minwage.htm (last accessed September 2017); U.S. Department of Labor, “Fact Sheet 13: Am I an Employee?: Employee Relationship Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA),” available at http://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/whdfs13.htm (last accessed September 2017).