Lactantius, talking about those who were honored for virtuously seeking the highest good in truth, said that although they labored well, they could never attain what they wished. This is because the truth is found in God, and it infinitely and absolutely transcends human comprehension:

Lactantius, talking about those who were honored for virtuously seeking the highest good in truth, said that although they labored well, they could never attain what they wished. This is because the truth is found in God, and it infinitely and absolutely transcends human comprehension:

At the same time they spent labor and industry, because truth, that is, the secret of the supreme God who made all things, is not able to be comprehended by [human] ability and its proper sense. Otherwise, there would be no distance between God and man if human thought could attain to the counsels and dispositions of that eternal majesty. [1]

While God cannot be comprehended by us, because if he were, it would make us equal to or greater than him, we can come to know somethings about him. Not only can we come to know that he exists, we can know what he reveals of himself to us in relation to his economic activity with creation,

Certainly, by saying God is incomprehensible and yet we can know something about him leads us to a kind of paradox. How can we know something about God and know it to be true when we cannot comprehend him? Do we not need to know the whole of God to know and realize the truth of any quality which we attribute to him? This is a paradox which is found in common throughout many religious traditions, but especially in the three Abrahamic faiths of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

There are many different answers which can be, and have been given, to this paradox. Not all who believe in a particular religious tradition, such as Christianity, agree as to how this paradox should be resolved. On the other hand, many find themselves in agreement with the general direction in which members of other religious faiths deal with this paradox. What will be examined here is one meta-religious resolution to the paradox which, though manifesting itself differently in each religious tradition, is grounded upon basic principles which they agree in common. In this way, what will be shown is not to suggest that this common tradition which transcends religious affiliations must be accepted by members of each particular tradition, nor that how that tradition manifests in each religious faith will be identical, but that people of different religious background often come to similar questions and the way they resolve them can be insightful to each other.

What will be examined is the way in which this paradox can be seen discussed in various mystical writings from the Abrahamic tradition, as well as in the writings of the Neo-Platonic philosopher, Proclus. Through it there will be interest as to what a Christian, looking at and considering the ways this paradox is discussed and resolved in non-Christian faiths, can learn from what others say, even adapting notions or conventions of others, so long as the Christian realizes that in such an adaptation they are transforming the way the conventions are employed.[2]

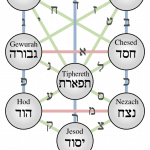

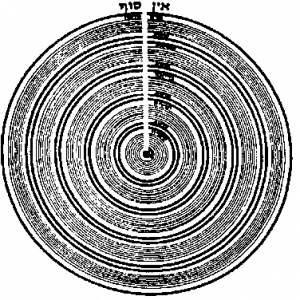

Rabbi Azriel of Gerona, writing about God as “Eyn-Sof,” the “endless one” as he is in himself outside of any creative activity, gives us a glimpse of the Jewish mystical understanding of the transcendence of God in the way he is in himself before and beyond all secondary interpretations of him:

Know that everything visible and perceivable to human contemplation is limited, and that everything limited is finite, and that everything that is finite is insignificant. Conversely, that which is not limited is called Eyn-Sof and is absolutely undifferentiated in a complete and changeless entity. And if He is [truly] without limit, then nothing exists outside of Him. And since He is both exalted and hidden, He is the essence of all that is concealed and revealed.[3]

Fundamental to this teaching about God as Eyn-Sof is the realization that as infinite and boundless, there is no way God, Eyn-Sof, can be named.[4]

Similarly, Islamic mystical teachings which follow the important but controversial Sufi Ibn Al’Arabi, agree, calling the inner nature or essence of God the Reality which we can never be known: “In this sense the Reality can never be known [by cosmic being] in any way, since originated being has no part in that [Self-sufficiency].”[5] Even the notion of this Essence, this Reality, being known and named as God, fails to reach the Essence as it is in itself, because by being named God, it connects him to his creation and ties him to a relationship with creation. He is God only because of creation, but since he transcends creation, he is beyond Godhood itself:

The Essence, as being beyond all these relationships, is not a divinity. Since all these relationships originate in our eternally unmanifested essences, it is we [in our eternal latency] who make Him a divinity by being that through which He knows Himself as Divine. Thus, He is not known [as “God”] until we are known.[6]

Al’Arabi and his followers suggest for God to be God, he needs something which he rules over, which he establishes by his action of creation. He is God because of creation, and without it, he is not God, thus, Godhood is a name which comes out of creation itself. This makes Godhood tied to contingent being, while the Essence itself is not. This is why God, as a name, fails to reach the inner nature of the Reality or Essence of that which is. On the other hand, nothing but the Real, the Essence as it is, can be said to be God, because it is in and through that Essence that Godhood is found. Reality transcends Godhood but yet when we are talking about God, we are pointing to the Reality itself:

The Reality, in Its Essence, is beyond all need of the Cosmos. Lordship, on the other hand, does not enjoy such a position. The truth [in this matter] lies between the mutual dependency [implicit] in Lordship and the Self-sufficiency of the Essence. Indeed, the Lord is, in its reality and qualification, none other than this Essence.[7]

From the Christian tradition, following the wisdom of Lactantius and other early patristic sources, the apophaticism of Pseudo-Dionysius also radically declared the One to be beyond all names and designations because it is beyond our comprehension. Dionysius, likewise, would agree with Al’Arabi that even the name God, or even the title of “the One,” fails to reach the truth of who and what we are talking about when we talk about God. The One who we call God not only surpasses the divinity and goodness, but it surpasses their source.[8] In this fashion, he cannot be grasped or imitated as he is in his nature infinitely transcendent to all contingent being. “To the extent that he remains inimitable and ungraspable he transcends all imitation and grasping, as well as all who are imitable and participate.”[9]

Proclus, representing the Platonic philosophical tradition, understood that there was one One over and above all things, indeed, the One must not be seen as any common thing, a being like all other beings. It is incomprehensibly transcendent and yet simple. What we know and understand is not the One in and of itself, but what comes subsequent to it, which is the foundation for the whole “order of the gods”:

As the first hypothesis, however, demonstrates by negations the ineffable supereminence of the first principle of things, and evinces that he is exempt from all essence and knowledge,—it is evident that the hypothesis after this, as being proximate to it, must unfold the whole order of the Gods. For Parmenides does not alone assume the intellectual and essential peculiarity of the Gods, but likewise the divine characteristic of their hyparxis through the whole of this hypothesis. For what other one can that be which is participated by being, then that which is in every being divine, and through which all things are conjoined with the imparticipable one? For as bodies through their life are conjoined with soul, and as souls through their intellective part, are extended to total intellect, and the first intelligence, in like manner true beings through the one which they contain are reduced to an exempt union, and subsist in unproceeding union with this first cause.[10]

Thus, we see there is a common a tradition which discusses how the One, God, the Reality or Essence which transcends all things, is in himself infinitely great, infinitely vast, infinitely above and beyond any created being, It is incapable of being named and yet is pointed to and discussed through various conventions, including but not limited to the terms God, Reality, Essence, and Eyn-Sof or “the endless one.” Even these conventions can be said to fall short of what it is but they are employed because they represent some of the best ways in which we can point to its transcendence. God, if we call him God, is hidden from us because of that transcendence, because of our inability to comprehend him; what he is in himself we cannot know because he transcends all notions which we would otherwise predicate to him (and for this reason, he can be said to be nothing, because all things which are used to suggest him ultimately must be denied of him).

[IMG= Ein Sof and angelic hierarchies [Public Domain] via WikiMedia]

[1] Lactantius, The Divine Institutes. Trans. Sister Mary Francis McDonald, OP (Washington, DC: CUA Press,1964), 15-16.

[2] That is, the very act of taking a non-Christian mystical text and engaging it as a Christian transforms the text with the Christian hermeneutic and so the Christianized form which comes as a result should not be seen as always following the original intention of the non-Christian authors.

[3] Rabbi Azriel of Gerona, “Explanation of the Ten Sefirot” in The Early Kabbalah. Trans. Ronald C. Kiener (New York: Paulist Press, 1986),89-90.

[4] See “Description of the Ten Sefirot” in Safed Spirituality. Trans. Lawrence Fine (New York: Paulist Press, 1984), 159.

[5] Ibn Al’Arabi, The Bezels of Wisdom. Trans R.W.J. Austin (New York: Paulist Press,1980), 56.

[6] Ibn Al’Arabi, The Bezels of Wisdom, 92.

[7] Ibn Al’Arabi, The Bezels of Wisdom, 148.

[8] See Pseudo-Dionysius, “Letter 2” in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works. Trans. Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 263.

[9] Pseudo-Dionysius, “Letter 2,” 263.

[10] Proclus, Platonic Theology. Trans. Thomas Taylor (1816; repr. Frome, Somerset: The Prometheus Trust, 1995),82.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook